Julian Hirsch was co-founder of Hirsch-Houck Labs, which for many years was the leading test organization in the HiFi industry, and provided the technical analysis for quite literally thousands of reviews in the mainstream audio and electronics publications of the time. In all of his writings for everything he wrote for, even his monthly "Technical Talk" column for Stereo Review, it's said (but I can't personally confirm) that he never even once commented on how anything sounded. For much of his hesitance to make any subjective comment, the reason was simple: like many a modern engineer and the people who share their point of view, he believed that talking about the sound could never be as accurate as measuring it, and that it would, in any case, "corrupt" the testing process. This is not to say that he didn't believe that there were audible differences between different products (especially electromechanical ones like speakers and phono cartridges), it's just that he didn't want anything other than demonstrable facts to influence his readers.

The one product area where he did (almost) voice an opinion was audio electronics. He believed that, with broad, flat frequency response utterly normal for the products that he tested, and with them almost always having less (often much less) than one percent of all measured forms of distortion, the audio electronics of his day were all essentially perfect and that, being "perfect," all would be identical in performance and must naturally all sound exactly the same.

Now, here comes the surprise; I agree with him, at least as far as he went: If any two of the same kind of thing—regardless of what kind—are both perfect, then it stands to reason that, just as they are identical in their perfection (How can one perfect "Thing A" be different in any way from any other perfect "Thing A"?) so must they also be identical in performance. And if the performance they deliver is sonic, then they must both sound exactly the same!

What that does, of course, is to expose, once and for all, the idiocy of the whole war over whether cables (and certain other products whose value is also hotly contested and declared to be the result of "voodoo" or the "placebo effect") make any difference: Either they are perfect (or perfectly worthless) or they are not. If they are either perfect or perfectly without effect, they must all sound exactly the same, and if they are not perfect or its opposite, unless they are all exactly the same degree of imperfect, in exactly the same characteristics—a circumstance that, given the wild differences in the nature, design, materials, and construction of the products in question, I can't imagine anybody believing to be possible—they will sound different!

I have never heard anybody claim that all cables (just to name one of the so-called "voodoo" products) are perfect, so I'm going to accept that they are not. And if that's the case, I must also accept the fact that they all sound different—whether I can personally hear or reasonably justify any difference, or not. You want proof? Simple: if there's no difference, they must all be perfect, and everybody knows that that's impossible—even for any one of them!

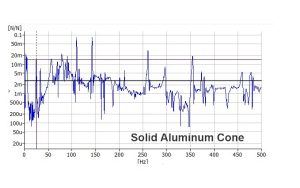

In reality, the issue isn't actually whether cables make a difference: Even the most adamant troll admits that cables can make a difference. He just insists that the differences are all based in the same four characteristics: Resistance[R], Capacitance [C], Inductance [L], and Characteristic Impedance [Z0], and says that any cable that makes an audible difference must be poorly designed for its application in one or more of those four things. If you're interested, Peter Aczel, one of the better-known cable-doubters of years gone by, wrote quite eruditely about this in his publication The Audio Critic. (especially Issue No. 17, Winter 1991-92)

So what it really comes to is that cable-doubters, fully aware of the effects of cables in some areas and from some causes (level loss due to excessive resistance, for example, loss of highs from excessive inductance, or dropouts in video images or digital signals caused by Z0 mismatches) don't actually deny the effects of cables; they mostly just deny either anything other than the four conventional causes for them or that anything that they can't measure can possibly exist.

And that gets us to the issue of placebo effect, which is nothing more than a fancier way of saying what Harry Nilsson said in his 1971 album and animated film The Point: "You see what you want to see and you hear what you want to hear." It's also where, contrary to the claims of the trolls, it becomes the "doubters" and not the "believers" who are exposed as being possibly a little crazy.

The fact of it is that placebo effect works both ways: Not only will it allow believers to hear things that aren't there; it will also allow non-believers to not hear things that are there! Unfortunately, most people either don't seem to understand this, or are so cowed by the claims of the orthodox that "If you can't test it, it doesn't exist" that they forget that just because a test can be performed doesn't guarantee that it's either valid or applicable, and that a negative result can just as easily disprove the test, itself, as the thing being tested.

Just one example of this is the germ theory of illness. Something like it was first proposed in ancient India and it was repeatedly proposed and denied in Europe, starting in 1546 with Girolamo Fracastoro, who asserted, but lacked the tools to prove it. Even when Leeuwenhoek, in the 1670s, using a microscope (first invented most of a century earlier by Zacharias Jansen), actually saw and described microorganisms, his discoveries were greeted by the orthodox with "skepticism and open ridicule" (HERE) and the germ theory—which today no one would dare to challenge—was not finally accepted until it was at last proven by Louis Pasteur in the last half of the 19th century.

What all this shows is at least three things:

1. It's possible for things to exist even if they can't be proven. Germs have always existed, whether or not anybody believed in or could prove them.

2. Tests don't necessarily mean squat: Before the invention of the microscope, you could test for germs all you wanted, but could never actually demonstrate their existence. Even today, if I look for them in a vessel of nitric acid or through the working end of a hammer, I won't see any. You have to have the right tools and be testing for the right thing under the right circumstances for test results to have any meaning at all.

3. Even if you have "good" test results, meaningfully derived and accurately presented to answer the right questions, it's not certain that anyone will ever believe them. The experience of Leeuwenhoek, and countless others, including, in our own field, Tesla and John Bedini, proves conclusively that proof isn't necessarily conclusive. People really do see what they want to see and hear what they want to hear.

Ultimately, it all comes down to this: All things that are perfect will sound exactly the same, and all things that are not perfect will sound different from each other. Placebo effect can affect either side of any issue, keeping both the believers and the non-believers hearing what they want to hear. And testing, just in itself, truly means nothing because we have no way of knowing if a test's results are either significant and relevant, or not, except from hindsight and further observation. In the meantime, all we can do is to apply logic, and logic tells me—and anyone else who is open to believe it—that no cable is perfect; that all cables are different in different ways or to different degrees; and that therefore, they must all sound different.