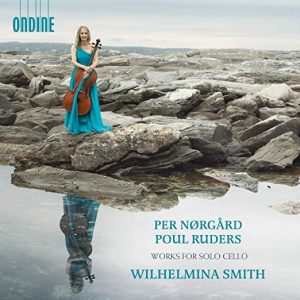

Per Norgaard, Paul Ruders. Works for Solo Cello. Wilhelmina Smith. Ondine ODE 1381-2

With much contemporary music composed in the high modernist idiom, we pretty much have to follow the composers to see where they go. Guidelines are hard to find. Is it an interesting place? Does the music speak to us? Can we infer anything from its intimations? Hear the song it sings?

This is solo cello music of two modern Danish composers performed by American cellist Wilhelmina Smith. The Scandinavian label Ondine obviously liked what she did for them on her Ondine debut CD playing Esa-Pekka Salonen and Kaija Sariaho, as well they might have, and so booked a follow-up recording.

She is an eloquent rather than overbearing and dramatic cellist, which suits especially the freewheeling soliloquies of Norgaard, enabling them to make their idiosyncratic cases without affectation. She seems to have a strong connection to his music as well as to the more forthright and engaging rhetoric of the generation younger Ruders. I find all of this music interesting and commend Ondine for finding Ms. Smith to present it.

Génératons: Senaillé - LeClair. Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord. Theotime Langlois de Swarte, violin; William Christie, harpsichord. Harmonia Mundi. HMF 8905292.

Jean Marie LeClair is one of the lesser gods of the French baroque, but he has always been a major one to me. (Cellist Wilhelmina Smith's mother and a University of Massachusetts violin student played him at our wedding reception!) Which is to say I will hunt for him wherever he's hidden in the huge world of recorded classical music—and recently found him in this marvelous new release from Harmonia Mundi. The violinist is unknown to me but the generation older Christie is one of the leaders of the Early Music movement as keyboardist and leader/founder of Les Ars Florissant. Together they play LeClair beautifully along with one of his lesser known contemporaries, Senaillé, whom they seek to make better known. It is always a good time to discover LeClair, if you've not already done so!

Lee Morgan, The Complete Live at Lighthouse (8 CDS). Blue Note Boo3 1953 92.

A lot of my Lee Morgan recordings are LPs—and I think this one is also available on vinyl. I'll check before sending this review off. But this new reissue of July 1970 live recordings (most of mine are from the 1960's) certainly makes a more than adequate case for its digital reissue: clear, incisive, dynamic, and rich. Bernie Maupin's occasional bass clarinet makes the case for the quality of this recording all by itself.

Like most of us, I admire and sometimes love Miles Davis but what I've always cared most about Lee Morgan is how he is unlike Miles. He is a jazz horn blower rather than a conscious jazz artist. And as a rule, he allows his fellow musicians to be as important as he is, though as a rule live performances tend to be a bit more democratic anyway. In this quintet especially reed player Bernie Maupin and pianist Harold Mabern are as significant to the whole performance as he is. And on some cuts, so is bassist Jymie Merritt and drummer Mickey Roker,

While Miles almost always feels eternal, Morgan is absolutely and completely of and in the moment. If straight ahead late 1960/1970's music is where you live, don't miss this release. And yes, turns out it is available on vinyl—same price for its ten LP's.

Joan Tower, Strike Zones. Evelyn Glennie, percussion. Blair McMillen, piano. Albany Symphony Orchestra. David Alan Miller. Naxos 8.559902.

Two works for virtuoso percussionist, Evelyn Glennie, one accompanied by orchestra, the other a solo; and two works for piano, also one accompanied by orchestra and one solo. All full of the boldness and brio we expect from contemporary American composer, Joan Tower. Gorgeous sound—remember when we couldn't say that about "bargain label" Naxos? That was a l-o-n-g time ago. Enjoy!

Beethoven, The Late Quartets. Brentano String Quartet. Aeon 1110, 1223, and 1438.

A favorite group of recordings re-surfaced at my house last week, the Brentano String Quartet's performances of Beethoven's late quartets. They struck me once again as holding the key to the frequent characterization of these late works as "modern," so I thought I'd write about them here in an attempt to clarify, at least for myself, what I mean.

One way of characterizing modernism in the arts is to say it is when we feel the content overcoming the form, the essence of the music (or visual image or work of literature), escaping the structure. In music we begin to hear this in Beethoven's Opus 127 and even more in its sister quartets—which to me is what is meant when we say Beethoven's late quartets are the beginning of modernism. In 1824! We can even hear Bartok in the finale of Opus 127! Clearly something new is happening here.

Of course art has always in varying degree resisted its form. Shakespeare's enigmatic Hamlet, referring to something beyond the drama before us to find meaning, Monet's impressionistic water lilies trying to reverberate beyond the pond and canvas, Henry James's intriguingly obsessive over-articulate late novels trying to make The Novel say, see, and hear more in human social relations than it has ever tried to say, see, and hear. Shakespeare, Beethoven, Monet, and James are not modernist, but we can feel it coming. When we reach what we have decided to call true modernism, the resistance sometimes feels like a change in kind not just degree. In the most radical cases, form seems altogether abandoned, simply cannot contain what the composer wants to express, for better and for worse.

Is it possible to play late Beethoven quartets un-modern? The late Beethoven of the Guarneri and Cleveland Quartets feels more restrained, more closely related to Haydn and Mozart—and earlier Beethoven; and they are much praised for it. But to my ears and sense of music history it's the Brentanos who get the modern quality of this music best, who hear its prescience, though the Emersons and Alexanders come close. The Brentano recordings were made in 2011-2014. They are every bit as exciting and "forward looking" as I remember. Here is the composer twisting, turning, as if to escape our melodic expectations, flirting with melody—sometimes for a whole scherzo-like brief movement—and then dancing away, as if to say, not so fast, true human meaning is not to be found in such easy phrases. We are used to this sort of compositional strategy now, but it was surely puzzling to early nineteenth century listeners. It is as if Beethoven is saying to them, music can do more than we are used to asking it to do. This music does not refer to other music but reaches beyond it, trying to include more of life than traditional music has done. Its reference is to the whole of human experience.

Systems used for this audition. #1: Resolution Audio Cantata 3.0 CD player w/BlackJack power cord, Gilbert Yeung Design solid-state NSI "G" 75 watt integrated amplifier, Jean Marie Reynaud Voce Grande loudspeakers, with Crimson interconnects and speaker cable. #2: Audio Note CD 5.1 CD player, Tonmeister Meishu Silver Signature 9 watt integrated 300B tube amplifier, and Audio Note E/SPe HE loudspeakers. Audio Note Sogon interconnects, Crimson speaker cable. Mapleshade Samson equipment rack. All CD's purchased from Presto, a superb international retailer in the UK. www.presto.com.

Bob Neill, a former equipment reviewer for Enjoy the Music and Positive Feedback, is proprietor of Amherst Audio in Western Massachusetts, which sells equipment from Audio Note (UK), Jean Marie Reynaud (France), Resolution Audio (US), and Gilbert Yeung Designs, formerly Blue Circle (Canada).