Jacob Holm-Lupo, Photo by Teresa K. Aslanian. Used with permission.

Jacob Holm-Lupo is best known as the creative force behind the Norwegian progressive rock band, White Willow, which was recently celebrated with a massive vinyl box set. He's also incredibly busy as a session musician, and is in demand for mixing, mastering, and remastering at his Dude Ranch Studio. He also co-runs the progressive music label Termo Records with Lars Fredrik Frøislie, which has released work by Wobbler and Rhys Marsh. In his free time he's written two books, one about Blue Öyster Cult and another about Toto, with a third in the works.

His newest project, which drops today on vinyl, is Mental Mutations, under the band name Telepath. It is a mostly instrumental homage to Italian and American rock soundtracks recorded for 80s sci-fi and low-budget horror films. Steeped in both metal and synth aesthetics, there's nothing low-budget about Telepath.

How did this project get started?

It started with a period where we had a lot of family visiting and, being the slight sociophobe I am, I would sneak into my studio at night to get some alone-time. I had this desire to record something a bit raw and visceral, and I started playing around with some riffs that I liked. Then I thought, since this is just me goofing, why don't I try to make it sound like a band, without there actually being one. So I played around with loops and samples and programming in addition to the actually played guitars and synths, and suddenly I felt like I had this sort of grooving, loose sound going that I really liked. I also really liked the sound of these doomy, thrashy 80s style riffs combined with my Oberheim synth, which has a really warm, nice sound.

In the end I suddenly had this whole pile of instrumental "songs" that all seemed to exist at a crossroads between 80s hard rock and Italian horror soundtracks. I sent some of the songs around to some buddies, just for laughs, but they really liked them. I thought, "maybe there is something here." Next thing I know, Apollon Records here in Norway wanted to release an album, and suddenly magazines were calling me wanting to talk about the project, and radio stations were playing a single we put out as a taster. It was all a very pleasant and unexpected surprise.

I've listened to it several times and it really is fun! There's lots of tight playing, but there's also many little tidbits that seem to reference things, here and there.

It was pure fun. I was smiling and laughing while doing it, and there's all kinds of silly in-jokes that only I know about. If I had known, from the beginning, that this would be an actual release I would have gone about it differently, found a really good drummer, maybe a singer, and made sure it was all in "good taste," you know? But I think the actual secret to this "success" is that I didn't! I didn't get great musicians, I didn't think, how can I make this pass the "rock snob test." I just went ahead and goofed and fooled around, and I think that's exactly why it ended up sounding alive, ironically, since so much of it is studio trickery!

Did you study music formally, in a classical context?

No, but I did take classical guitar lessons, privately, for a few years. That's the only guitar training I have.

What were your early exposures to music?

On my mother's side, Simon & Garfunkel, The Beatles, and Bob Dylan. From my dad, classical music, especially Mahler, which is his favorite. As I got old enough to buy my own records I started out with Paul McCartney. My very first record was Tug of War. I progressed to New Romantic stuff like Ultravox and such until heavy metal became the big thing among my friends. Simultaneously, I discovered prog through an older friend, and that was that.

Prog covers lots of ground. Was there a particular flavor that grabbed you?

It all started with a tape of Genesis' Duke that this friend gave me on my 12th birthday, which would have been in 1983. That tape was all I listened to that summer, and I felt that it was a perfect marriage of the music I grew up with—the beautiful melodies of folk-rock and 60s pop, and the grandiose, majestic sound of classical. So I worked my way backwards through the Genesis catalog, fell in love with the [Peter] Gabriel era, of course, but also never abandoned my love of Collins-led Genesis.

From there, a cousin of mine guided me towards King Crimson, then I discovered U.K. and Yes, and then me and a friend also started to get into the music sold by Recommended Records, so we started digging Henry Cow, Matching Mole, Magma, and those more 'out' things. They were exciting times!

When did you decide to create your own music?

I started fiddling a little bit with writing chord progressions a while after I took my first lessons. I remember the first "complete" song I wrote was called "Voices in the Wind," and I was probably 17 at the time. A year later we recorded it with my first band, which went through a number of names. My favorite was Sparrow Cemetery. The concept of the band was a sort of acoustic folk-jazz thing, half-way Jethro Tull and half-way early Metheny.

Has that track been released?

No, it's a terrible recording! Very amateurish. It wouldn't be until a few years later that I did anything good. After another band project had sort of folded, I met Jan Tariq Rahman, who had been in the periphery of my orbit for a while. He had some cool instruments, and he came over to my place to try jamming a little for the first time, to get to know each other musically. He brought a Clavinet and a Mini-Moog and we sat on the floor in the living room and made "Snowfall" in about a half hour—the very first White Willow song. That was the first time I ever felt, "Yes, that's it! That's the music I want to make!"

So, from the outset, the process felt very collaborative?

Yes, those early White Willow days were very collaborative and democratic, and we all learnt a lot from each other. Our musical selves were formed by the interaction between Jan Tariq, Tirill Mohn, Audun Kjus, and me. It was a very important, formative phase.

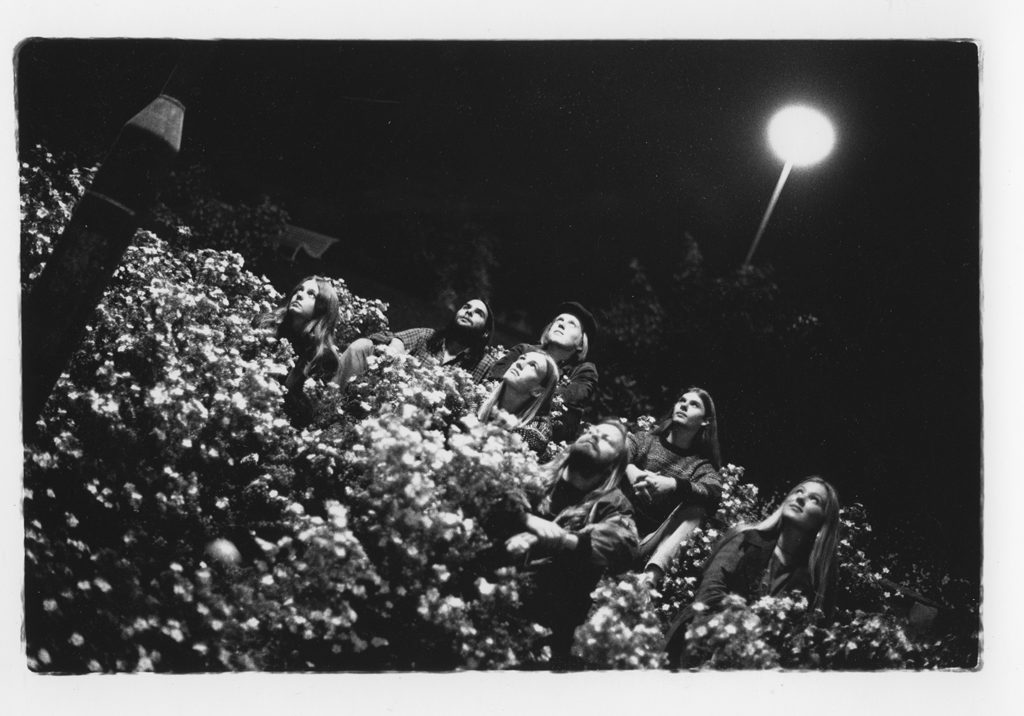

White Willow, circa 1995. Photo by Erik Borchsenius. Used with permission.

What happened next?

We got a contract with Ken Golden's The Laser's Edge, recorded an album, then it all sort of exploded. [It went] from being a little hobby project that only our friends and parents knew about to being something that connected with an international prog scene that we had no idea existed.

We were invited to Progfest '95 and had to assemble a band that would function in a live setting. When we went on stage in Los Angeles for Progfest, that was our second concert, ever! So it all happened a bit too fast.

In the aftermath our energy dwindled a bit, we wanted different things. I was never the muso type, more of an introvert, sit-at-home-and-compose-and-dream type, so when some wanted to pull the band in a more fusion/prog metal direction I felt a bit alienated, and the whole thing eventually fell apart. I started writing material on my own that eventually led to a second White Willow album, Ex Tenebris, where Mattias Olsson was the savior from Sweden who came and injected some prog energy into it.

After Ex Tenebris I realized I wanted to get back to being serious about the music stuff, and I wanted a real band. That's when I came into contact with Ketil Einarsen, and we got a solid band together that composed and rehearsed for a long time and then released Sacrament, which I think was the first really solid White Willow album.

What was the origin of The Opium Cartel?

After "Storm Season" and "Signal to Noise," I was getting very tired of the confines of making prog, with the solos and the time changes and all. I really had a need to do something else, and we also had a line-up at the time that wasn't really working out on a personal level, so I decided to end the band and do something completely different. I think we did our last gigs around 2007, and then we quit.

I had gotten myself some home recording equipment and decided to just have fun and fool around with material on my own. That eventually became the first Opium Cartel album, that I released on the label that Lars Fredrik Frøislie and me had started in the aftermath of White Willow.

It must have felt entirely different to work in a more solitary way. What was that like?

I loved it, and decided never to go back to working in a band setting. In fact, when I decided that White Willow would cease to exist as a regular band, it was some of the happiest times of my life. No more traveling to crummy hotels, no more arguing during endless rehearsals, no more compromising on my material. So it was great. When I did go back to recording White Willow material, it was as purely a studio project, and purely dictatorial. Wonderful.

One of the things I love about Night Blooms is that it seems to encompass all of your influences in a lovely, pure way.

Yes, I think that's right. It was a distillation of everything I wanted to do, without being filtered through anything else. It was gentle, melancholy folk, it was electronica, and it was prog in the sense that it had some synth/mellotron orchestrations and some extended arrangements, but without any of the "ego-tripping."

When you re-imagined White Willow, did you have a sense of the voracious demand from fans?

Voracious is maybe a bit of an exaggeration, but yes. People had been asking. Mostly though, it felt like the time was right again. I had spent a period revisiting some of the Italian prog that was a big influence on our debut album, and some of the old love for the genre was flowing back in me. So I made Terminal Twilight, the first WW album I recorded and mixed myself. It is almost a bit of a tribute to bands like Le Orme, who I love dearly. I felt, with that album, that I was back to making White Willow music for the right reasons, for the love of the music rather than to try to please fans or labels or critics.

It has been more than two decades since the release of the first White Willow album, and the most recent, Future Hopes, was released in 2017. Can you tell me about how the box set came into being?

I was simply contacted by this South Korean label, Hi-One Records, who told me that they wanted to release an exclusive box set of all the White Willow records, plus bonus material. To be honest, it took me a while to take them seriously. I thought, at first, it was a joke or a hoax but, eventually, I understood that they were dead serious.

I spent a long time trawling the archives for the best quality masters, and looking for unreleased tidbits like demos and live recordings and such. They did an unbelievable job. I have no idea how something like that works, economically. It must be insanely expensive to produce, and the audience must be fairly limited, but I am very, very grateful that they did it. A labour of love on their part. According to their website, they produced 25 copies, and have 5 left. For a set that costs $730, that's amazing! Again, I just don't know where they find the audience, but good on them!

As you know, I interviewed Ketil Vestrum Einarsen about Weserbergland. What was your experience working on that first album?

I love that album! I think it's the very best thing Ketil had done up to that point. I think, much like me with The Opium Cartel and Telepath, Ketil realized that the best thing was to throw caution to the wind and just do his thing, other folks' opinions be damned.

I think the songs are just amazing, because he combined his classical training and formidable theoretical knowledge with his love for very untrained music like shoegaze and Kraut [Rock], and that combination really works.

The musicians all did a wonderful job: Gaute on those jazz-on-amphetamine guitars, and Mattias' hyper-kinetic drums. I was also really happy about the sound we found for the album, which was a lot more gritty than anything either of us had done before. So, to me, that album is pretty much perfect.

And the new stuff: I really like that he doesn't give a damn about expectations, He went ahead and did a completely different, and just as amazing, thing. This time he flirts with serialism and minimalism and all kinds of things. He is prog's mad scientist.

As a complete outsider, and with a filtered perspective, it seems to me that there's an unusually large number of extremely talented and interesting musicians in Norway. Any idea why?

I think there are, and I don't know for sure, but I have some theories. One is going to upset your Republican readers: We have a very good system of free musical education. There is something called Kommunal Musikkskole, which is a free music school in each county, and tends to have very good teachers. In general, the whole education system for music is very good, and free. So that's one thing.

Then, I think it might be a bit of a climate thing. We spend a lot of time indoors in places like Norway, Sweden, and Finland, because of the long, dark winters. And one of the most obvious things to do to kill time during those endless winter months is to play an instrument. We have a strong musical tradition here, going back to old Norse folk music, and then via the Classical era with Edvard Gried, and then finally the explosion of Norwegian jazz talents with people like Jan Garbarek and Terje Rypdal.

Music is a big part of life, here, and we have role models that everyone looks up to. That is part of the explanation, but I am sure there are other reasons, too.

I have to ask you about the series of books you've been working on. What possessed you to write Blue Öyster Cult: Every album, every song?

Stephen Lambe, who runs Sonicbond Publishing (and who organizes the Winter's End/Summer's End prog festivals in England) knows about my obsessions, so we discussed the possibility of doing a book and, since the first one (Blue Öyster Cult) did fairly well, I am now allowed to do a Toto book and, after that, a Steely Dan book. These are three bands that I am deeply obsessed about: Fascinating bands, fascinating songs, fascinating stories.

Can you summarize the sources of obsession for these bands?

With Blue Öyster Cult it's the combination of that slightly psychedelic and harmonically smart hard rock with lyrics that are so literate, so mysterious, and so funny at the same time. It's like Lovecraft, The Marx Brothers, Black Sabbath, and The Doors rolled into one, or something like that. Plus, great, great songs. [As for] Toto, it's just the grooves and the textures and the jazzy bent of the chords. It's music that flows so easily that you get curious about how they do it. With Steely Dan, it's the way they are so subversive, with that slick surface sheen to the music, the dark, dark and sarcastic lyrics, and the insane musicianship. I relate to the way they just holed themselves up in the studio and ate up studio musicians and were never really happy.

What kinds of information do you include for each song?

Each chapter is about one album, and opens with credits and release info before delving into the songs. I've included some musical analysis, some lyric deciphering, and some general cultural context. Sources are personal insights, interviews with artists, biographies and, of course, some music theory goes into it as well.

The Opium Cartel album you've been working on is nearly complete, and expected to be released in early 2020. What process did you use to create the songs?

These days I sort of write, demo and record material simultaneously, since I do it all in the studio. So the road from writing a chord sequence and a melody to having a finished accompaniment is fairly short. Then I shop the song around to the the people I want to overdub. In the case of the new album it's mostly a very talented singer, Silje Hoge, who writes insane vocal arrangements and really elevates the songs, a guitarist/bass player named Ole Øvstedal who shares my love for Blue Öyster Cult and is a great player and extreme audiophile, and then Lars Fredrik Frøislie will be the drummer. He will be the last to overdub, and then we're done.

One fun thing is that the album will sport an amazing cover by photographer Glen Wexler, who has made covers for Rush and Van Halen, and who had the help of people from Cirque de Soleil help him with this particular photoshoot.

Speaking of cover art, your last White Willow album had some good work from Roger Dean, perhaps best known for his iconic, other-worldly album art for YES. How did that happen?

We first met him at NEARfest 2001 when we played there, and he and his daughter liked the music. I had always wanted to ask him to do a cover, but there was the issue of money. For Future Hopes, The Laser's Edge graciously agreed to put some money on the table, and Roger ended up making a perfect cover that really reflects some of the, well, hopeful aspects of the album's lyrics.

There is another thing about Roger that needs to be said: He is an incredibly warm and kind person, really a one of a kind guy! I spent my school days making bad versions of Roger Dean logos. It was the dream of a lifetime.

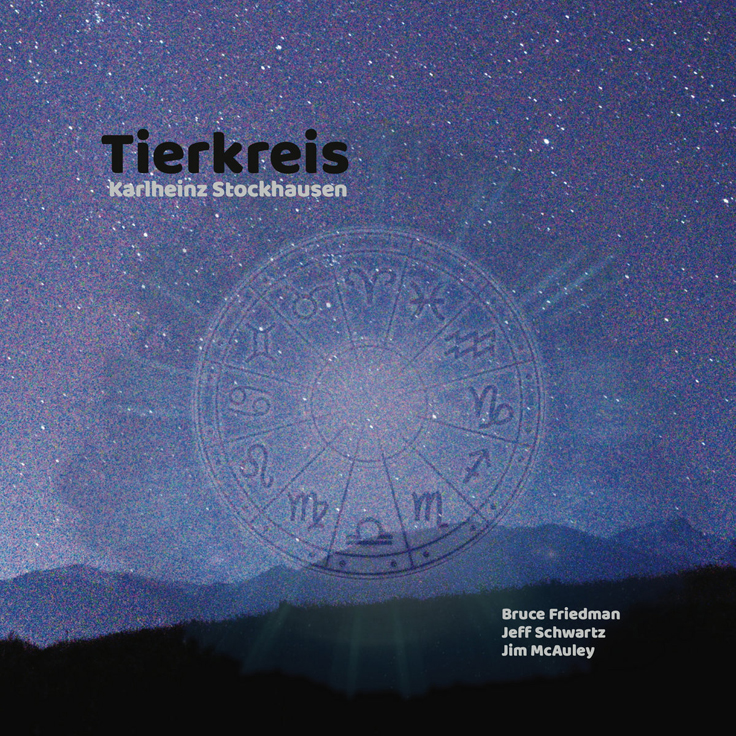

Listen to "Escape from the Witch House," a rather spectacular track from Mental Mutations, by Telepath.