"I began playing with Dixieland bands in the late 1950s, and those older musicians made it a point to insist that I listen to the music of the great New Orleans drummer Baby Dodds, which was like the best thing that ever happened to me. I went on to be influenced by the likes of Zutty Singleton and Big Sid Catlett, and then at about that same time, I heard the great drummer Max Roach performing with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, and Charlie Mingus on that famous Jazz at Massey Hall recording, and that was completely inspiring—Max was a complete musician, and he showed how musical the drums could be and how a drummer didn't have to take a back seat to anyone."

"It was during this period, early on, that I was playing with a big band in an Irish club, and the horn player couldn't figure out how I was playing every single note of the jig right, when he caught me reading the tenor part over the saxophonist's shoulder. I mean, it was a big band, and you had to read, right, and he encouraged me to study some harmony, and while I can't play actual tunes on the piano, I can play any chords you want to hear, and I learned to write. There was Basic Harmony by Piston, with all of this figured bass and basic rules of traditional harmony, and I sort of married that to the Schillinger Method. For instance, you're not supposed to employ parallel fifths and octaves, which I tend to use sometimes; also, in Schillinger, he'll always have two lines moving in opposite directions, and I write a lot for horns like that."

Which goes a long way towards explicating the contrapuntal element that has long been such an identifiable aspect of Baker's polyrhythmic approach to the drum kit, most notably on his signature drum showcase, "Toad" from Fresh Cream, the trio's maiden voyage in 1966, where his hands and feet often sound as if they're going in opposite directions , as the call goes out to swing your partners, like in a square dance, in a swelter of crossing patterns as executed by some giant web footed amphibian, redolent of Duke Ellington's drummer Sam Woodyard (who inspired Ginger to begin playing double bass drums) or the ceremonial aspects of African drummers in collective ensemble.

"Phil Seamen was one hell of a drummer and a beautiful cat. Phil was the one who got me into African music. I was playing a gig at the Flamingo All-Nighter, where the saxophonist Tubby Hayes heard me and straightaway went off to tell Phil that there was this drummer he just had to hear. Well, when I got off stage, there was Phil Seamen to greet me. I mean, I was just in awe of Phil—he was the king of British jazz drummers—just a master player. He took me back to his flat, right, and he began playing all of these polyrhythmic African percussion records for me. ‘Okay, where's the beat?' And straightaway I got it—which shocked the hell out of him. ‘You're the only one who's ever understood how this music goes."

And years later, with his own Air Force, Ginger got to repay the love, show his mentor how far he had come, and to share the spotlight with Seamen when they engaged each other in a drum duet on Baker's "Toad" showcase.

"You see, African time is very simple, but very complex. In African music, everything is layered—time is more evident in the rhythmic pulse.

"The Africans modulate rhythmically, whereas in western music, a piano player might modulate harmonically, with chords.

"They'll start with a four; then put a six over four; then they play on the two threes of the six; and then a twelve over the four and an eight. In Africa, especially with the Yoruba, all of these are going on at the same time, and nine times out of ten, it's a little kid playing the four. And he just sits there all night long and never changes, playing four to the bar. And the other drummers change the patterns on top of the four and it'll sound very different, and yet the tempo remains steady.

"I practiced all of this a great deal. So I might play eight beats to the bar on one bass drum, four on the other, and with your hands playing twelves and twenty-fours and threes and sixes. It goes into the realm of madness. In mixing those up, it sounds as if you are playing things incredibly fast when you get the bass drums coming in between the triplets. If we were boxing, you wouldn't see it coming. There's no doubt where it comes from—it always lands on the second of the three, the one you don't see. That in-between beat is the basis of what I've been doing for years."

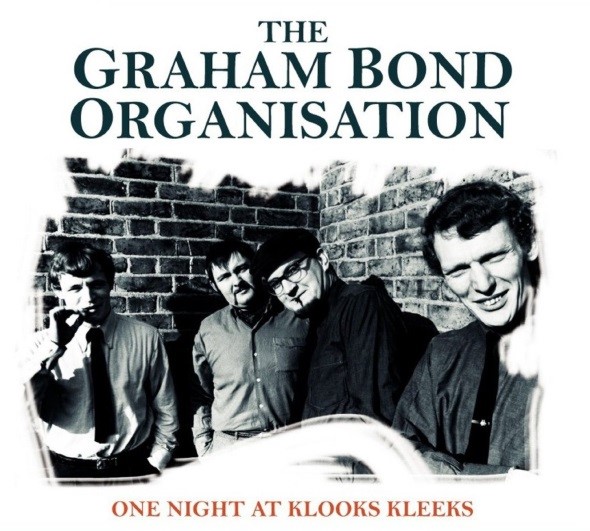

Early on in the young drummer's evolution, this became a defining feature of Ginger Baker's emerging ambitions as a modern jazz player, best documented by a live set from Klook's Kleek in a quartet chaired by organist-saxophonist Graham Bond from 1963, featuring fellow jazz puppies John McLaughlin on electric guitar and Jack Bruce on acoustic bass.

In this performance of "The Grass Is Greener" you can discern stylistic echoes of one of Ginger's abiding heroes, Art Blakey (and intimations of directions Tony Williams was then pursuing unbeknownst to Ginger, in a parallel universe across the pond…least ways that's what I've always discerned vis a vis the distinctive manner in which they both deployed their hi-hats as a time-keeper…but hey, that's just me, though it's worth noting Tony Williams and Ginger Baker had great admiration and respect for each other, and in later years became good friends and collaborators).

However, coming of age in late 1950s/early 1960s Great Britain as Ginger did, when boundaries on the London music scene began to break down, and the likes of Cyril Davis and Alexis Korner began to champion a nascent new style based on American folk forms, as a practical matter, given how challenging it always was to make a living playing modern jazz, many jazz players gravitated towards opportunities in the emerging British Blues scene.

And when drummer Charlie Watts stepped aside to give Ginger the drum chair in Alexis Korner's Blues Incorporated (Ginger returned the favor, hooking Charlie up with Brian Jones in what became a formative version of the Rolling Stones), Ginger's found his niche in a stylistic gumbo of Blues R&B and Jazz, culminating in the drummer's musical breakout as a member and titular leader of the Graham Bond Organization.

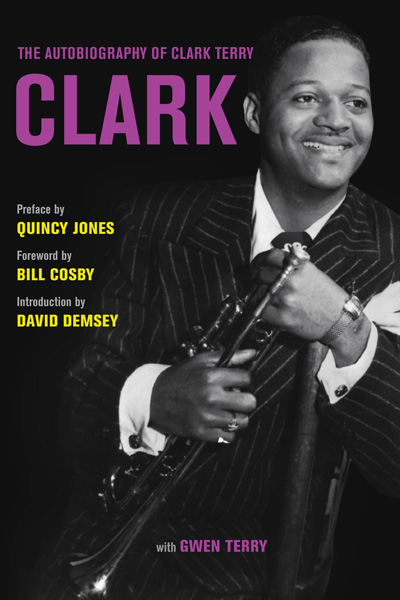

This popular band helped put Ginger on the map, and cement his reputation as one of England's finest up and coming drummers, featuring as it did Bond's trademark Hammond B-3 organ and soulful vocals, along with significant contributions by his other mates from Blues Incorporated: tenor saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith and his battling brother, bassist Jack Bruce—thus inaugurating a tempestuous, combustible creative relationship which somehow endured for fifty years.

The Graham Bond Organization was an enormously popular and influential band on the British music scene, which marked Ginger's coming of age both as a composer/arranger and as a drum stylist. You can hear it coalesce conceptually on Ginger's early recorded drum showcase, "Camels & Elephants," echoing as it did his African influences, on what was then your standard-issue four-piece, single bass drum kit. But there was nothing standard issue about the richly articulated, singing tonality which he elicited from the kit.

"So many drummers sound like they're hitting a practice pad or a lump of wood or a chair. If they hear a tone in the bass drum, they think something's wrong. Man, drums have got to sing, like an instrument. I tune my drums; they're in tune with the guitar—I've always done it that way. And when musicians were tuning up, I'd be tuning up as well, right? And some of them used to get riled up, because here are two of them trying to get in tune with each other, and I'm tuning up my tom-tom. And when you're the youngest person in the band, everyone would tell you, ‘Fuck off man…shut up, we're tuning up—leave it out.'"

At then, at the point where Ginger felt Bond's concept had run its course, the drummer was determined to start a band of his own—the idea being to feature "the cream" of British musicians—reaching out at first to guitarist Eric Clapton, late of John Mayall's Bluesbreakers, and then at Clapton's behest—much to Baker's chagrin—to bassist Jack Bruce, with whom Baker had famously feuded in the Bond Organization (and who would continue to piss each other off, while reuniting to play again and again and again over the decades).

For the better part of two years, Cream was the most popular touring band on the contemporary music scene, paving the way for the birth of progressive rock and heavy metal bands such as Led Zeppelin on one hand (an honor for which Ginger vehemently denies paternity), and the emerging jazz-rock fusion movement of no less a figure than Miles Davis and bands such as guitarist John McLaughlin's Mahavishnu Orchestra on the other.