Making the simple complicated is commonplace.

Making the complicated simple, awesomely simple, that's creativity.

- Charles Mingus

Years ago my friend, the British guitarist Robert Fripp (of King Crimson renown), found the time for a brief assignation at a Greenwich Village bistro. Over lunch, when I inquired as to how his visit to Manhattan was going, he smiled wanly and sighed: "Everyone is mad at me Chip: All the people I haven't seen—and all those I've only seen once."

Back in 2000 I had my one and only opportunity to spend about a half an hour on the phone with the trumpet and flugelhorn master, the inimitable Clark Terry, one of the most beloved figures in the history of American music.

To me, Clark is the Johnny Hodges of the trumpet, one of the few brass players of whom it may be said that he had command of the trumpet and not the other way around. And while that may indeed be an illusion, Clark has always had a way of making the trumpet and flugelhorn do his bidding, with an ease of execution, a burnished tone, a sophisticated harmonic sensibility, a deep feeling for the blues and a degree of rhythmic-melodic fluency that are as warm and elegant and ebullient as the man himself.

The occasion was the 2000 release of fourteen lovingly recorded encounters with some of the finest piano players in jazz for the Chesky label, entitled One-On-One, appropriately enough—a gloriously joyous, engaging recital.

That brief encounter with Mister Terry was one of the greatest experiences in my life. I have never met such an affable, nurturing, engaging soul; a truly loving, gentle man, and not only a master performer and instrumentalist, but a conduit for the entire history of jazz, much of which he had experienced first hand, with a great teacher's gift for distilling things into deceptively simple maxims and lessons, making the medicine go down easy—and imparting the belief that, hey, stick with me kid, you can do this, too.

At a number of points in our conversation he illustrated some musical or technical point by vibrating away—not on his horn, nor on a mouthpiece—but on his embouchure, chops alone, buzzing away by bringing a forefinger to his lips. Did I say buzzing? When I affix my forefinger to my lips, on a good day I might emit some vague semblance of sonic flatulence. When Clark got to buzzing, there were notes, overtones, even chords—with nothing but his chops, Mister Terry sounded for all the world like a Bach Cello Suite. We are talking tone, people. TONE FOR DAYS. Each and every note an embryonic being encapsulated in the glowing amniotic fluid of…soul.

I was flabbergasted. He made the basic principles of the trumpet come alive as no one ever had; in fact, his demonstrations were so inspiring, I thought, "Hey, I can do that."

Well, not really, but I remember getting off the phone with Clark (way sooner than I wanted, but even back then his health was beginning to go south, and I didn't want to wear his ass out) and thinking, "Man, if I am ever privileged enough to get some more face time with this wonderful spirit, I am going to damn sure know more about the horn than I do now."

Indeed, I sought out a trumpet, and in time my dear friend, the great trumpeter Ron Miles, gifted me a 1911 Holton Cornet. I practiced it for a while and got some rudimentary insights into the overtone series and how you made a sound. Let me tell you, if I ever respected trumpeters before, I really respect them now, and was even more in awe of Clark Terry's mastery and spirit.

My brief encounter with Clark was a truly life-changing experience, and became part of my recombinant DNA. And while I never did get to speak with Mister Terry in a formal setting again, I checked in with him and his wife Gwen regularly at his Arkansas home during the final furlongs of his illness, and did my level best to help raise funds for his care, to promote his book, and to get the word out about Alan Hicks' wonderful documentary [KEEP ON KEEPIN' ON] chronicling Clark's end days and his enduring love & power as a teacher/mentor in a nurturing relationship with blind pianist Justin Kauflin.

Clark passed away in 2015 after a long, harrowing, debilitating illness, and while I was shaken by his death, I consoled myself with the knowledge that this gentle giant was now one with the universe and out of pain.

Still, it is always too damn soon to say goodbye.

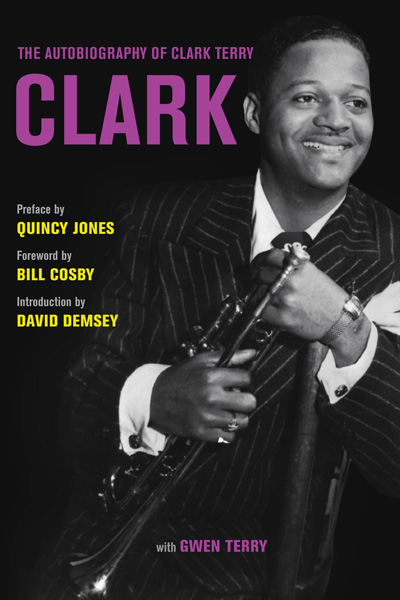

That being said, now that Clark Terry belongs to the ages, allow me to once again recommend that you purchase a copy of Clark: The Autobiography of Clark Terry and allow Clark to do the talking instead of me.

And while Radio Free Chip could expound at great length about his history, all the wonderful music he has made, musicians he has mentored and lives he has touched, instead allow us to allow this brief encounter, and some musical examples, do the talking for us.

Mandala by Mary Morgan Stern

I met you at Max Roach's birthday party a few years ago on the upper East Side. You and Sweets [Edison] sashayed in wearing a couple of full length fur coats, looking like a couple of collegians. I was sure you were going to bust out a couple of ukuleles and break into a chorus of "Boola-Boola, Boola-Boola." [Laughter] I wanted to let you know that I just wrote about the One on One album for Stereophile. That's quite a splendid recital, sir.

Oh, thank you. How do you like the concept, where I have a different piece of music for each of those pianists to use?

I think the concept gives you a wonderful range of repertoire.

Covers a lot of history.

It shows off the breadth of your range. How much flugelhorn did you play?

I played them both at the same time. I played trumpet and flugelhorn on practically every track.

Well, that clears that up. I was thinking, "Damn, Clark sure gets a dark sound from the trumpet." [Laughter] Were you sending out a message to Papa Jo on "Swinging the Blues?"

Yeah, how about that? [Clark elicits air effects from his chops which mimic the iconic sound of Papa Jo's hi-hats]. He was the master of that. Not too many people can do that right…yet!

What is it that makes one particular style of horn a jazz instrument as opposed to a symphonic horn?

For the trumpet?

Yeah, like a Martin Committee.

Yeah, I have a Martin. In fact I'm using a Martin Committee now. They gave it to me as a 75th birthday gift at the JazzTimes Convention. Miles used to have them dip them in all those dyes. Blue, black, green, yellow, white, purple…Miles would pick up the phone and tell the people, [growls] "Green!" and they'd make him a green one. Tell 'em "Blue" and next week he had a blue horn.

Had one to match all of his outfits [laughter]. Wallace Roney was playing a black one that Miles was using. I played it once. A nice horn, and it's just like the old Committee Martins which I had for years. So he said, "I'm going to get 'em to give you one," and I said "Yeah, sure." And sure 'nuff, two-three years later they did give me one on my 75th birthday. And so I've been using that religiously since then. But as far as comparing them with classical type instruments, they're basically the same. It depends on what gets the best results for you. Wynton Marsalis all of a sudden feels that the mouthpiece should be continued through the rest of the horn and not detach.

Those custom-made Monette horns with the integral mouthpiece. My buddy Ron Miles plays one.

It wasn't invented that way, but as the old saying goes, "Different strokes for different folks." So some people like heavy horns for classical or jazz. Some like light, quick horns. Some like plated; some feel that the silver horns are more conducive to playing brassy-type sounds; other folks feel that gold gives the tone a darker character. I don't do a heck of a lot of lead playing anymore; in my younger days that's what made me choose the Selmer flugelhorn, because it sort of made me go back to the days when the Jimmie Lunceford Band used to play flugelhorns—all of the guys in the section from time to time just to change the mood. One of those flugelhorns is still around. Sy Oliver had one, and he passed.

And that reminded me of going back to get this type of sound. So much so, I used to put felt hats over the bell of my trumpet to sort of get that sound, close to that sound. And we had a chance to do it. We worked with Keith Ecker, who was a technical adviser for brass to Selmer, and we put together a horn in his basement while drinking his home-made red wine [laughter]. And put it together and sent it off to Paris, and they checked it out mechanically and made sure it was okay, then they gold-plated it and sent it back to me. And in November, 1967, they sent it to my friend in Chicago, Syke Smith, who came over at the Blue Note. And at that time we were recording with Billy Taylor, doing a thing of his called Taylor Made Jazz, with all of the members of the Ellington band. And Sykes brought it down to the studio and opened the box, and there was shiny, beautiful flugelhorn horn, and I played a few notes on it, and Billy said, "Why don't you put that on the date?" And I said, "I intend to." So I played it on the date and went to club that night and he wrote a piece for me on the flugelhorn, first piece he over wrote for me—called "Julieflip on the Flugelhorn."

Is it a different kind of tubing than the trumpet?

The flugelhorn is actually in the cornet family in that it's conical shaped from the receiver straight through to the bell; gradually gets bigger all the way through the bore both ways. Whereas the trumpet goes one bore until it passes through the valves, and then it flanges at the beginning of the bell.

So that would account for the brilliance of the trumpet and the mellowness of the flugelhorn.

Absolutely. Right.

Is there any difference in terms of blowing into it in terms of air pressure.

Oh, yes. It has been said that they're illegitimate scales, so you have to be very, very tender with them to achieve…you can't blast 'em; you can't over-blow them—you can't be too cruel with them [laughter]. You have to be very careful, because they can very easily be played out of tune if you don't know how to use the tuning slide.

Ron Miles explained that on the cornet, it could be a little sharp in the bass, and a little flat in the upper register, and that you have to compensate as you're going along.

Well, it took us years to really do some serious research on the flugelhorn, to figure out that you need to tune each pump instead of in one spot with the tuning slide. And the tuning slide on the flugelhorn is in the leader pipe; as you enter the mouthpiece into the receiver, then after you've made your regular tuning, you tune each pump, each slide individually and pull them into a position where it's more conducive to you to make the notes that you want using that combination of valves…in tune. So the minute you see a flugelhorn player, unless he's been doing it for a long time, playing with all of these pumps—middle valve, first valve and third valve—not being altered somewhat or tuned, you can almost bet he's going to play out of tune. It's sort of like a violin or a trombone. Each little position may be marked—first, second, third, fourth—and if you go to the second position and it's a little bit flat, you're going to pull up a little bit with your lip or your slide; the violin the same thing. What might be an A on the violin for one player might be a wee bit sharp or flat for another player. So they have to adjust according to their articulation, manipulation and their ear. So there are a whole lot of things that go into producing one tone. [Laughter.] On the flugelhorn, the violin…any instrument.

But even on the trumpet, Clark, you get such a dark, creamy sound: I always refer to you as the Johnny Hodges of the trumpet. When you were talking before of the relative intonation in relation to somebody's A, the way Hodges would play he would slide up and down to the point where he was almost outside of the scale, but it always sounded in tune, and it was so…what do they call it in opera? Bel Canto.

Well, that's one of the things where we have a lot of difficulty teaching students: To find the center pitch of their tone—the center of their tone—and to be able to maneuver. This is one of the lessons that we were taught by the old timers that are not in the books. They used to say, "Son, you've got to go back home and learn how to bend that note." Which means coming from below [sings upward bend] and find that pitch before you vibrate or go down to it [sings a downward slide]—but maintaining the center of the pitch in your mind. It's not an easy thing. It's not nearly as easy as some people think it is.

I remember hearing this black mezzo-soprano in a Verdi opera, and she came out with this big, pure voice, and hit every note right on a dime, and the audience was kind of underwhelmed. And then this woman came out in the role of a gypsy woman, and man, to my inexperienced ears her vibrato was all over the place. And the people went nuts, and I figured, "well, I guess I don't know the tradition." It was not very pleasing…to me anyway.

Well, look at Johnny Hodges. He could actually milk it, but he would always get to that pitch before he vibrated or changed.

All of you guys with Ellington could do that. You and Johnny…and Barney Bigard in particular used to kill me with all of his bends on the clarinet. Getting back to your gear, have you used the same mouthpiece for years, or do you tend to fotz around?

Yeah I've played the same one for quite a long time. I got the mouthpiece I'm using now years ago. And when Giardanelli started making mouthpieces he looked at mine and decided he would make a bunch of these with that same sort of dimensions as some of the already standardized mouthpieces. And at the same time we were going through a thing here in New York, where most of the brass players, we had discovered that in the orchestra, all of the French horn mouthpieces were V-shaped, straight down, and flat-rimmed. You never saw a French horn mouthpiece with a bowl or cup. They all go straight down. So we came to the conclusion that this is far more conducive to what we were after than any other configuration. It's good for longevity; it's good for intonation; it's good for range; it's good for sound.

So we decided to get into that, and Giardanelli fixed a couple of them up like mine, with a flat rim and a V-shape; and it's comparable to somewhere between a #3 or a #5 Bach mouthpiece. And it seems to be a mouthpiece than almost any player can use. So we recommend something similar to that for students who get involved, because it gives you the flexibility and maneuverability to keep a nice range and a good sound. Some guys get on a versatile kick and they want to play higher than anybody, so they have a mouthpiece with a thimble for a cup and a pin-hole for the bore. It lets them play high, but then they can't make a sound to match anybody else's in any orchestra or big band.

Some horn players used to assert as how Cat Anderson had a trick mouthpiece. And I'd ask them "Does he have a trick lip, too?" [laughter].

He had a trick everything [laughter]. A trick neck, a trick attitude. He was a strange cat.

Doc Cheatham told me that Cat would go through a three-card montie game with his mouthpiece, where he'd employ one mouthpiece to play all the section stuff and match everybody, and then when it got to his part in the score where he needed to ascend into that upper register netherworld, he'd kind of palm it and nobody would ever see him put the other mouthpiece in.

Well, he may have done that in his early years, but I used to watch him, because I'd sit next to him, and I never saw him do that. He reached the point where he could do anything he wanted to do on one mouthpiece. And I don't think anybody else in the world could make a sound on his mouthpiece, but him. And his lower register was big and his upper register was big—so he mastered that thing.

A lot of guys who can take all sorts of deficiencies and make something positive out of them, like the trumpet player… Byron Stribling? He plays all wrong; up under the lip on the soft part of the lip, but he has mastered that fault of his and instead of correcting it, he's mastered it. And he plays great. He has a big sound and his range is fantastic, so he never bothered about changing the mouthpiece.

I had a little friend from London who played almost like Byron, and I couldn't stand the sight of him [laughter], so I asked him if he would give me two weeks to correct it. And he said okay, but that "My teacher said that it was okay." And I said, "Well, you tell your teacher…blahblahblah." And I had him do what we call the tuck and roll, where you tuck both lips over the top of the teeth and then a little roll down to that area where you can make a buzz [makes the most powerful, amazing buzz sound I've ever heard]; when you can make that buzz so that you can control it and put it right there [makes it dance up and down in identifiable phrases, concluding with low register descent]…when you reach that point than you know you're in the right area, but if you go to far over into the red part [indistinct flapping sound] you can't make any upper notes. So it has to be close to center. Well, he did this for about two weeks without his horn, and then used his mouthpiece, than he put it in his horn, and now he plays five notes higher, his tone is bigger; and besides that, he won the honors of the little girl singer in the band [laughter].

When you were making all of those different sounds, I was thinking of how you described the French horn mouthpiece, and a lot of their training involves controlling the tone without the valves, going back to the ancient horns.

Sure, that's exactly the same principle that we use when we use on the bugle [plays long complex phrases with deep descent into lower register] without valves. As a matter of fact that's why there are so many good Mexican trumpet players…what do you call them cats, the mariachi? They were taught to use the mouthpiece long before they were allowed to touch their horn. So that's why you never hear of any of them Spanish or Mexican players having trouble with single, double or triple tongues. They always have excellent articulation. And that's because they were taught to play the mouthpiece first—master the mouthpiece. Like boxers say, "Kill the head and the body will die." [laughter].

I hung out with Dizzy one afternoon in his basement, and we were watching television. I set up a sound system for him and put on the delta bluesman Robert Johnson, and I listened to Dizzy warm up on his mouthpiece for close to an hour, and that's all he did was mouthpiece, playing along with Robert Johnson. And he had all sorts of articulations with just his mouthpiece, and it occurs to me that all of those different tonguing techniques and such, they really aren't taught much anymore are they?

No. It really isn't. There are so many things that are just skipped over in teaching things, and a lot of it needs to be learned.

I like all kinds of music from all generations. I'm not stuck in any one bag, but a lot of the horn players these days sound more like classical trumpet players than jazz players in terms of articulation. I mean, in listening to a master player such as Maurice Andre, he gets that brilliant kind of shimmering tone, but there's not much in the way of those vocal inflections that were such a vital part of the early jazz vocabulary.

The reason being Chip is because not that many people are conscientious enough to teach kids from whence you come. So they don't know for the most part about bending a note, finding that center pitch; they don't know about moaning and what you call flips—things that we learned from the old-timers. Which are not in books: like shakes, fall-offs, rips, doinks, buzzes and things that were concocted by the older players. Because of the fact that most trumpet players of that period who got involved years ago, they had no teachers, so they saw all of these instruments in the pawn shops which had been ostracized by the classical players, such as the cornet, and things like that. And there wasn't much call for these types of instruments, so the pawn shops were loaded and cats saw these shiny instruments in the windows and they were self-taught.

They didn't know the proper place to place the mouthpiece on their lips: over on the right corner, on the left corner, over towards the upper lip, down towards the lower lip, almost on the cheek—and so they couldn't produce a proper sound. So as a result, they couldn't produce a sound that was good enough to fit in a section and play a part with legitimate sounding players. So as a result of that, sometimes their tones would be kind of tinny. So somehow they had to find a way to make their sounds more acceptable, so they began to do what we now call buzz, which simply means to hum as you produce your sound, which makes your sound bigger [produces a lip tone then adds a moaning sound an octave below, a la Slam Stewart].

Roy Eldridge used to play like that, and [trombonist] Vic Dickenson, even the saxophone players such as Ben Webster and Coleman Hawkins—they all used that sound. So buzzing became a very important ingredient. Now not too many legitimate teachers would even bother to want their kids to know that shit. And I think it's very important that they do know it. As well as the three areas of the tongue that are very, very valuable for producing different sounds: the tip of the tongue which is a flutter; and the back of the throat is called a growl, like a dog; and then way down in the bottom is the hum.

So you've got all three of those areas, which along with the manipulation of the plunger—another forgotten instrument—can produce all sorts of wonderful sounds. Like a type of tonguing called the doodle system: a-e-i-o-u, in order to prevent the kids from reiterating the second syllable. The -dle in the word doodles, the last syllables are ghosted, they're swallowed: D-Dood. So it's daadle, deedle, diidle, doodle duudle. And if they don't learn to do that, they're going to play dato, deto, dito, doto, duto. You want noodle soup, you don't want noodo soup, because noodo soup don't taste like noodle soup [laughter]. So these are some of the things that a few of us, some old folks who are still around, like to impart to the kids. And please believe me, it makes for a much better player when they couple that with the legitimate techniques.

Oh, I'll say, except for the fact that I could never get a sound out of the trumpet, you make me want to pick up a horn right now [laughter]. Still, I think I better stay with my guitar and drums. That's amazing information to pass on. I heard a story, I believe Nicholas Payton told me, and I don't know if it's apocryphal, about how you took Dizzy to some classical teacher.

It's true. About the time Dizzy came through East St. Louis with his big band, the Board Of Education was doing a crackdown on professors who would teach their kids who really idolizing these people, and most of them puffed their cheeks way out like Harry James and Dizzy; so they went to Harry and Dizzy and told them what was happening with the kids and that all of these young horn players were puffing out their jaw. And after they told Harry, bing, just like that he quit right away and just played…he was phenomenal, just a phenomenal trumpet player—and he stopped puffing his cheeks and could play the same way he did when he was puffing his cheeks.

And so Dizzy came to St. Louis and asked me to take him down to Joe Gustav, who was a very domineering type of personality who would scare the hell out of you. "Play something for me." And Dizzy went…[sings a boppish descending phrase]. So he was walking away when Dizzy played that, and he whirled around and said "Do that again." And Dizzy did something even more spectacular. So he says, "Play me some eighth notes, and Dizzy says bip-bip-bip-bip. "Faster!" and Dizzy goes bipbip-bipbip-bipbip-bipbip. And each note his jaws would fill out like a bladder. And Gustav says, "How long have you been doing that?" So Birks, answered, say "Well, I'm sorry G, but I've been doing this all my life." And he say, "Well, you just keep doing it—now get the hell out of here." And that's a fact.

Puffing the cheeks is wasted energy.

That's right; it's wasted energy, and it impairs the continuity and the flow of the air column from the diaphragm. Kids need to concentrate on it almost like karate—HAH!—when you go through the brick you've got to keep a steady flow of air, with evenness in your air column. And that's kind of hard to do when you're puffing out your jaws; that's all it is—very strenuous. Extra energy is expended. And it's harder on the body.

Is that why Dizzy had such trouble with his intonation when he got older?

I think so, yes, because he didn't start right, you know and couldn't overcome that…one thing I think is fascinating is that he started out playing just puffing a little bit, and then as his muscles started getting weaker and weaker, he had to put more and more air in there to support the air column.

His wife told me he didn't start out like that, but as the years passed, his cheeks came out more and more.

If you look at pictures of yesteryear, he just puffed out a little bit in one cheek.

Right, like when he was with Cab Calloway or Earl Hines.

That's right. And then he started more and more and more, and it got to the point where the more he filled up, the more he needed filling to support the air that came through—it had to go past those wind pockets.

It used to make me mad when people would jump on him at the end, because Dizzy wanted to die with his boots on…

Yeah…[sadly]

And guys either want you on an exercise cycle or six feet under, and I mean, fuck you, man.

That's right…

But I'll tell you what, all the times I saw him live during his twilight years, no matter where his pitch might have been that evening, when he got to "Round About Midnight" he was home. In retrospect, it seemed to me that he was such a virtuoso; he had set the bar so high for himself and everyone else; he had defined such a profoundly rhythmic style, that there was a lot less room for error as he got older.

Absolutely.

But then again, Miles used to have a problem with that as he got on.

Well, Miles used to have a problem in the beginning, too, before he had really perfected the sound he wanted. Miles was one of the few St. Louis cats in his age group who didn't study with Gustav. But his teacher, Mister Elwood Buchanan, did study with Gustav. So Miles always followed the Harry James thing; he loved vibrato. And when he commenced to vibrating, Mister Buchanan always kept a ruler with some tape wrapped around it, and he'd tell him "Stop shaking that goddamn note, 'cause you'll be shaking enough when you get old," and he would hit him with the ruler.

Well, that'll do it.

So there was that, plus the fact that Miles just loved those Heim's mouthpiece that Joe Gustav insisted all of his students play: a very wafer-thin mouthpiece; deep but it was curlicued outside and it was a bowl—and he always insisted that all his students play those Heim's mouthpieces. So Miles would always have me running around hunting for Heim's mouthpieces. See, my chops were a little bit too thick to use those little thin curlicue mouthpieces, so I had to resort to something similar to a Rudy Buck back in those days. And I'm sure Mister Buchanan rapping his wrists with that ruler, in combination with those Heim's mouthpieces, helped him to develop a straight, pure type of sound. When he first came to New York, Bird couldn't stand his sound. If you ever notice on all those records they made he had the mute in. They'd be playing and Bird'd say "Put that damn mute in." [laughter]

I was thinking about the mouthpiece and the size of the chops, and what you explained to me before when you were talking about hearing the center of the note…when Miles was with Bird, he really didn't have that, did he?

No he was still working on his tone.

Although harmonically and rhythmically he sure seemed to know his way around.

Oh yeah, his rhythm patterns were beautiful. Same thing about a St. Louis trumpet player. See, St. Louis was always known as a trumpeter's town, all the way back to Charlie Kirk, who had a big sound. For some strange reason, trumpeters from that area always had good rhythmic patterns, because there were a lot of good drummers around there, and all the boats that came up from New Orleans stopped in St. Louis. They were enticed to stop there because the rents were reasonable, the food was good, the booze wasn't over-priced, and the ladies were pretty and very encouraging.

And that became a very integral part of the perpetuation of jazz. There was Charlie Kirk, and he had a big sound, and then there was Levi Madison, who had the prettiest sound in the world, and people used to go over to listen to him practice outside of his apartment; and he was a bit weird, because he would practice for about five minutes, then he would laugh for ten or twenty minutes [laughter]. Play something pretty, then look in the mirror and laugh his ass off. So we'd jump down and not take a lunch just to hear 32 measures, you know. And there was Hamp Davis—no relation to Miles—who used to be the preacher of all the parades. And St. Louis was a parade town; every day there was some sort of parade—and they couldn't do a parade without Hamp, because he was the only cat in the world that knew all of them marches, and played every one of them an octave higher with one hand.

Good, God…

With his other hand in his belt or in his pocket, and he glided gracefully through the pot-holes and never missed a note. And there was Crack Stanley, Baby James

Was Freddie Webster a St. Louis man?

No, I don't think so, unless he spent a little time around there. Like Sweets was not really from St.Louis…

They just claimed him.

Yeah, so there was a while host of trumpet players for us kids to learn from. And traditionally there were a lot of rhythmic things that we covered in playing with the older guys.

You know, Clark, I could talk to you forever, but I don't want to burn you out, but we need to continue this at some point because what you're talking about needs to be out there—it cannot be lost. The tradition in which guys like you learned, it sounds like you were blessed to able to reference a combination of the classical tradition and the oral tradition, so you have that balance in your playing, and now the young guys have got all of the classical finesse, but they don't have a connection to the oral tradition, and also they don't have…it's like comparing people to Sonny Rollins in the '50s. First, he was a different person back then, and second, it was a different time socially….

Absolutely.

I mean do we want to go back to the way America was in the '50s and '60s just to get better jazz?

No.

I don't think so, but there's a certain depth and richness to the vernacular you and cats of your generation would've gotten from playing a whole gaggle of gigs that had nothing to do with jazz. Lester Bowie, who was from St. Louis, told me about playing with medicine shows and circuses and the last generation of black vaudeville; growing up in the south—experiencing all sorts of things which are life things, and that's a vital part of the music…

Absolutely.

And that's what people really don't get when they're writing about it. It's not just about the notes on the record—it's about a spiritual and cultural and a social context.

Absolutely.

So that's what I want to expand on after the summer, perhaps. In the meantime, thanks for everything, sir, and God bless.

Mandala by Mary Morgan Stern