"Yeah, that was about the same time, wasn't it," Ginger allowed, with a rueful smile. "That was a sort of thing he did. I don't know—kind of madness really; how'd Elvin Jones put it—delusions of grandeur. That about it sums it."

Returning for a nonce to "Crossroads," and its enduring impact on drummers, bassists, and especially guitarists, Ginger often observed to me that in his estimation what made Eric Clapton special in this regard, and set him apart from other guitarists, was that "Eric has time." And over the years, in speaking with Ginger, he repeatedly doubled down as to deeply he perceived TIME as a vibrational constant and spiritual reality: "It's just natural, like walking or breathing or looking out a window. It's there—it's always there. If the power of the basic time is right, then everybody can relate to it—everybody.

"Time isn't free, man. No way is it free. It is a di-mension."

Likewise, as per Clapton's dim view of his solo on "Crossroads," it is worth noting that it does not take place in a vacuum, but is part of a larger ensemble dynamic, that was purportedly edited down to a manageable 4:25 by Atlantic Records' master engineer Tom Dowd (himself an excellent musician).

Be that as it may, there is a storytelling sensibility to the collective dialog, a sense of inevitability to the time. The manner in which Bruce and Baker interact frames Clapton's guitar choruses in an ever-shifting rhythmic/melodic canvas, as Baker supercharges and balances out Clapton's swinging linear lines and Bruce's aggressive counterpoint by engaging them in a dramatic game of hide and go seek that distinguishes the very best jazz ensembles.

It's not so much that Clapton's solo is the apotheosis of blues guitar, but rather, the manner in which Bruce and Baker respond to Clapton's soaring lines, his impeccable phrasing, with buoyant, super-charged variations on a New Orleans shimmy—continually upping the ante—that lends such an air of excitement to this collective snapshot of band so in tune with themselves, and that is what has allowed "Crossroads" to retain its dramatic edge after all these years.

But for this listener, it is the master take from Live Cream, Volume 1 of "N.S.U" (an acronym for Non-Specific Urethritis, a form of venereal disease, if you must know), that has long defined the enduring power of Ginger's conception and musicality, and the singular manner in which he engenders excitement, or as Bill Frisell so aptly puts it, "He's listening like crazy."

The escalating tension and pliant rhythmic-melodic push-pull of Bruce & Baker's raga-like variations, creates a shifting canvas that projects the transcendent danger and dynamic interplay of free form jazz, the earthy snarl of the Chicago Blues and the dancing joy of West Africa and [trust me on this one] the Russian steppes.

But what is most remarkable and enduring about the Baker-Bruce dynamic is the ongoing tension between their contrasting rhythmic conceptions, threatening to melt down and implode at any given moment (much as the contentious personalities of these battling brothers often clashed violently over the years).

You see, Bruce tends to push things forward, playing well ahead of the beat with a forceful contrapuntal conception, while Baker has a tendency to play behind the beat, somehow accommodating the bassist's aggression without mitigating the elemental power his own web-footed ritual overdrive, deploying heady tom-tom/double bass drum orchestrations to flesh out many of those accents that might normally be the purview of the bassist—as Bruce abdicates the traditional role of the bassist while scampering to trade melodic lines with the guitarist. Bruce and Baker push and pull obsessively at the pulse as if it were a giant wad of taffy, the bass going west, the drums to the east, stretching this convulsive pocket to the breaking point without releasing the reins on their respective horses, inspiring Clapton to one of his most gripping and fully formed solo journeys, as he builds and builds and builds, culminating in a fully realized, collective catharsis.

Okay, it's not the Coltrane Quartet, but close enough for jazz, one might say. Anyway, I JUST SAID IT.

Ironically, Cream's unique brand of collective improvisation, and the spontaneous buzz I got from Clapton, Bruce, and Baker, led me directly to the majestic energy and devotional dignity—to that sense of DANGER, of soaring above the earth without a net—that distinguished the colloquy of John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison and Elvin Jones…of Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams…of Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, Charlie Haden and Ed Blackwell…of Charles Mingus, Dannie Richmond, Ted Curson, and Eric Dolphy—of balls to wall, no-compromise, playing as if it were your last fucking evening on Planet Earth…JAZZ.

And when, within a year after The Cream dissolved, and Miles made his transition to the surrealistic, fulminating electric keyboards, grounded figured bass and snarky electric guitar of Bitches Brew, well, it was a natural transition for me, and as such Ginger Baker's approach to the collective ensemble continued to resonate with me every bit as much as it did when I subsequently heard the likes of Baby Dodds, Chick Webb, Big Sid Catlett, Papa Jo Jones, Max Roach, Roy Haynes, Art Blakey, Philly Joe Jones, and Tony Williams.

Nor was I the only one hearing the confluence of all these rhythmic tributaries, suggesting as they did new possibilities, upon an electric jazz-rock canvas, triggering a coming of age by the likes of great drummers such as the youthful Tony Williams with his band Lifetime and those drummers who seemingly found inspiration in Elvin and Tony's breakthroughs; Billy Cobham with the Mahavishnu Orchestra; Jack DeJohnette with Miles Davis and his own Directions; Alphonse Mouzon with Weather Report and Larry Coryell's 11th House; Lenny White with Freddie Hubbard and Return to Forever; Mike Clark with Herbie Hancock's Headhunters.

And while in no way, shape or form am I suggesting that any of them were necessarily emulating Ginger technically, or beholden to him stylistically, the genre in which they all took flight—championing as they did a dynamic new style of virtuoso rhythmic engagement—surely emerged at that juncture in time where Ginger and The Cream left off. Baker opened the door and a generation or three of drummers came charging through the breach—liberated from a subservient role, an equal partner in the musical ensemble.

Because, once again, at the risk of repeating myself, Baker's command and projection of such a very personal polyrhythmic vocabulary connected the modern jazz of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane, to the blues and parade rhythms of Congo Square in old New Orleans, with their primal roots in West Africa.

And again, quiet as it's kept, while most of the Ginger Baker obituaries seemingly reference the same received wisdom as to how Ginger Baker's enduring legacy was as the world's greatest rock and roll drummer—not to mention a disagreeable asshole of Biblical proportions—in point of historical fact, Baker was a transitional figure who bridged the divide between popular music and jazz; between the vertical and the linear; between backbeats, swing beats, and Afro-Beats.

In no way, shape or form, was Ginger Baker your standard-issue time keeper, but rather a tribal elder of the talking drums, and as such, inspired generations of rock drummers, while engendering an abiding passion for music in this aspirational puppy, in my own journey as a drummer, and more significantly as a devoted jazz aficionado and scribe—with a taste for borderless music and cultural miscegenation.

"The 1960s was when everything sort of amalgamized into one movement," Ginger once reflected, "and that was really nice. Since then, it's diverged off into a thousand little splinter groups, and I don't like that. But I was never a rock drummer, for fuck's sake," Ginger was wont to tell anyone who cared to listen, repeating this basic reality to me time and time again with considerable exasperation over the years.

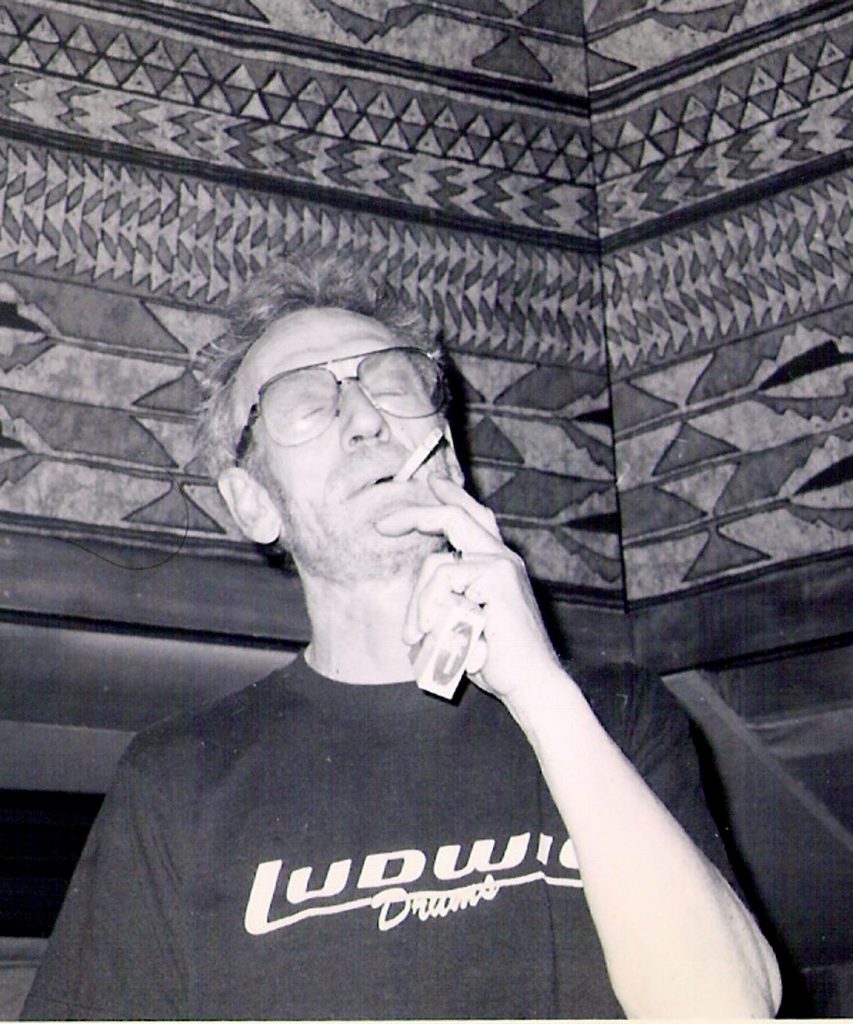

Ginger Baker [Ocean Way Studios, 1994]. Photo by Chip Stern

"You see, I'm a frustrated musician. I think of the drums as a musical instrument—I've always tried to play tunes on them—to tell a story. Writers like to lump everything into these bloody little bags so they can label it. It's just plain stupid. Music transcends all of these absurd categories. To this day, people insist on characterizing Cream as a rock and roll band. Bollocks!"

"Yes, we played songs and sold a lot of records, but it was basically improvisation on a lot of blues stuff and original material with a very jazz-blues influence. Jack Bruce and I cut our teeth on the modern jazz of artists like Sonny Rollins and Charles Mingus and Ornette Coleman in the early ‘60s, and Eric was a master blues player with impeccable time. Because of our musical roots, when I first put the band together, and we had our initial play at my flat in 1966, the connection was magical and instantaneous—the neighborhood children were dancing about outside. Then in 2005, when we got together to rehearse for four nights at the Royal Albert Hall, having not performed in public since 1968, it was like we'd just been off on holiday for a few weeks. The chemistry was still there."

Perhaps Ginger enjoyed this special affinity with Jack and Eric because of how he initially was introduced to the instrument and came of age as a drummer. "I was always banging away on this metal desk in school with a wooden top, that was hollow inside, and I'd get all the kids to dancing. Then there was a party with a band playing, and the kids kept insisting that I sit in, and I discovered that I could play the very first time I ever got behind a real kit."