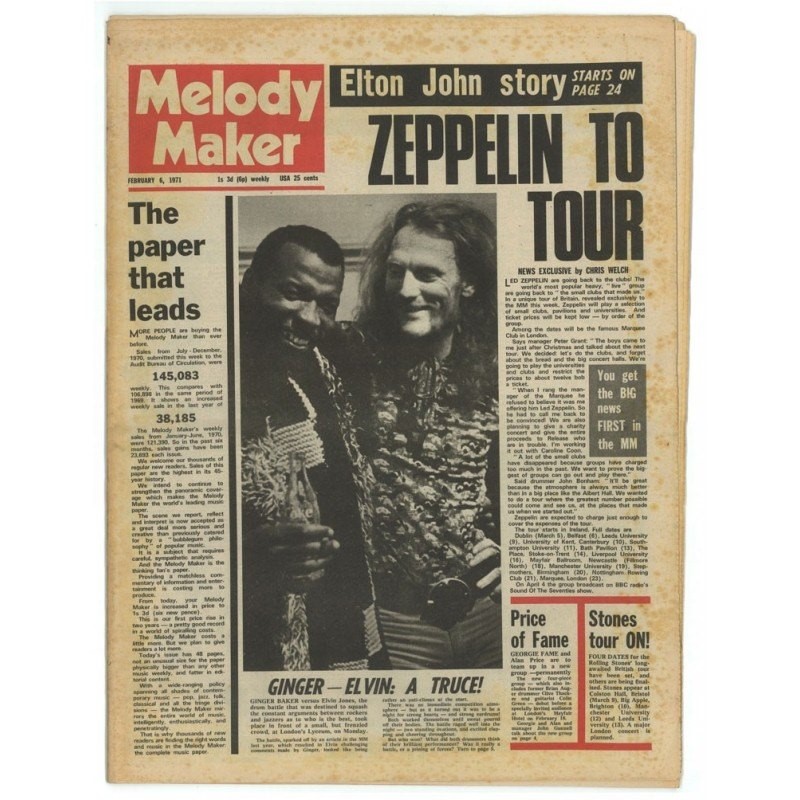

Photograph courtesy of Nettie Baker.

Vex not his ghost. O let him pass. He hates him

That would upon the rack of this tough world

Stretch him out longer.

William Shakespeare

King Lear

"If you knew Time as well as I do," said the Hatter,

"You wouldn't talk about wasting it. It's HIM...

I dare say you never even spoke to TIME."

Lewis Carroll

Alice in Wonderland

When I first heard Cream's single "Strange Brew," this baby boomer was but a mere tadpole, who'd come of age listening to my parents' RCA Red Seal classical recordings and popular ‘50s show tunes, subsequently wending my way through the folk of Dylan and Simon & Garfunkel, the folk-rock of the Byrds, Motown, and whatever rock, R&B, soul and pop music I heard in passing on WABC-AM/New York, or at sleepaway camp in the Bear Mountains, wherein through bonding with Black and Hispanic kids I was exposed to a cultural polyglot quite unlike what I'd encountered through my white bread upbringing, growing up as I did, both literally and figuratively, in Plainview of Hicksville, in the Duchy of Long Island.

I was immediately taken by the supple musicality of this trio; their heady balance of structure and spontaneity; and just how much raw horsepower was clearly idling beneath the hood—as they split the difference between what I came to know as the linear rhythmic flow of jazz, the convulsive backbeat of rock, and the sweet earthy snarl of the blues in all its acoustic and electric incarnations.

In short, The Cream triggered my subsequent immersion into AMERICAN MUSIC, albeit, reconfigured for our Earthly delight by three very British musicians.

Nor was Ginger simply playing beats or keeping time: he was playing parts and making time, orchestrating on the fly with conversational cadences that blurred imagined distinctions between front line and back line, between melody, harmony and rhythm.

There was a song-like logic to the manner in which Baker's drumming engaged and amplified the syncopated bass playing of Jack Bruce and the feral melodic cry of Eric Clapton's blues figurations. What's more, I discerned a harmonic fullness and rich melodic tonality to Baker's contrapuntal drum parts, wherein you could sing them just as readily as the vocals they so elegantly shadowed.

As an aspiring drummer myself, I discerned a heady elegance and sense of danger to the collective call and response Baker's rhythmic orchestrations triggered, and a Mozart-like logic to Ginger's drum parts, not unlike the sensual sense of inevitability bassist James Jamerson conferred upon all of those chart-topping Motown arrangements, wherein you could not imagine one note more, nor one note less. Baker and Jamerson were great improvisers, with readily identifiable sound signatures, whose every response rang true—played it as they felt it, played it like they'd written it.

And much as Detroit's heady jazz paladins of the recording studio made the sound of those Motown classics resonate with a certain Biblical certitude, rather than being too smart for the room, Cream struck a remarkable balance between the rock song-form and jazz/blues improvisation, juxtaposing elegant pop craftsmanship with a spontaneous sense of power and intellect, taking unsuspecting audiences and radio programmers of the mid-1960s by storm.

For this nascent hipster, drawn as I was both as a listener and a participatory aspirant to all of the instruments in what came to be known as the power trio, Ginger Baker, Jack Bruce and Eric Clapton defined my expanded expectation of what the drums, the bass guitar, and the electric guitar were capable of—without truly comprehending how comprehensively they had captivated my imagination.

Or, for that matter, how they straddled the sundry creative tributaries of American music, igniting as they did a lifetime's passion for modern jazz (initially through my Road To Damascus discovery of John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Charlie Christian, Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, Art Blakey, Clifford Brown, Max Roach, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Booker Little, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, Cecil Taylor, Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Louis Armstrong, let alone such blues icons as Robert Johnson, T-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Albert King, Freddy King, Otis Rush and Buddy Guy), all the while triggering an intermittent pursuit of my own elusive drum, bass and guitar playing muse, let alone an unbridled passion for musical instruments and high end audio—which continues to this day. As a cautionary tale, all I can say is…be careful what you wish for, fellow Pilgrims.

Having devoured the studio craftsmanship of the variegated song forms on Disraeli Gears countless times from top to bottom, and likewise the band's maiden voyage—the more primal, bluesy Fresh Cream—I subsequently came to experience how committed the trio was to a free form style of collective improvisation on the live sides from their Wheels Of Fire double-album with its classic rendition of "Crossroads," while their extended variations on "N.S.U" (which first appeared on Live Cream, Volume 1), offered a deeper dive into those March of 1968 Winterland concert performances wherein "Crossroads" came from. Between "Crossroads" and "N.S.U" my deep dive into Ginger Baker's drumming, with its unique blend of melodic tonalities, emotional commitment and heady conversational engagement henceforth became an indelible part of my own recombinant DNA.

Now most fans of The Cream are familiar with the band's epic variations on "Crossroads," which has long been esteemed for one of Clapton's most dramatic solos, though ironically, the guitarist himself has pronounced himself baffled as to this performance's enduing luster, as he once explained to a well-respected colleague, one of my favorite rock scribes, David Fricke of Rolling Stone.

"There's a couple of big myths about me," Clapton related to David with some exasperation: "This thing about God and this thing about ‘Crossroads.' I think that's a terrible solo…I really appreciate that respect for it, but I can't figure out what the hell they're talking about. It's messy. I admit it's got tons of energy, but that alone doesn't make it. I don't like it. Isn't that funny?"

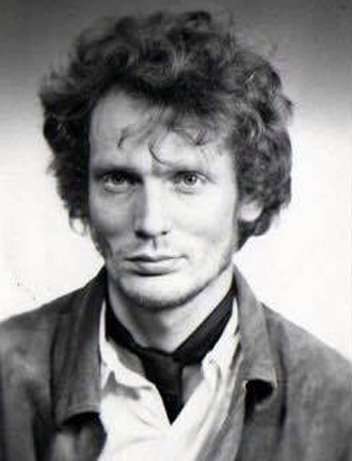

One needn't be surprised. Not unlike other master musicians I have known (Sonny Rollins leaps to mind), no one can ever be half as critical of Eric as Clapton himself. Likewise, no one's judgement can ever be quite as damning to Baker the drummer as that of Ginger the musician, or as he told me when first we met: "I'm not terribly keen on a lot of stuff that I played with Cream, actually. The studio version of ‘Sunshine of Your Love' is probably the thing I played best on of all the Cream things. I listen to some of those things now and I hear how I could have played them all better. I don't know...you get to a stage where you get too busy, play too much; this is part of maturing—of getting older. I was obviously trying to show everybody that I could do it—that's where I was coming from."

Not unlike how you were often quoted in the press coming off like a polyrhythmic Muhammad Ali, wherein you'd proclaim your prowess—the world's greatest drummer—and offer to take on all comers.