This is the third installment of John Marks' very helpful series that guides our readers through various aspects and considerations for digitizing their LPs. In it, John...he of The Tannhauser Gate blog site...is seeking to help you by providing recommendations for quality components in a cost-effective way.

Could other components be used? Of course. But by giving you an experienced and intelligent starting point, John saves you the effort of starting from zero. And that is a real benefit, especially since so many audiophiles may not have any experience with the process at all.

And so, read and learn....

Dr. David W. Robinson, Ye Olde Editor

This is the third installment in my series about choosing Pareto-Optimal equipment to make digital archival copies of vinyl LP (long-playing) phonograph records. The first part (an overview) is HERE. Part 2 (Rega's Planar 3 turntable package) is HERE. But even if you are not planning to make digital transfers, you might be interested in my thoughts on turntables and phono stages.

Phono stages are necessary to (1) amplify the faint electrical signal generated (literally) by the phono cartridge, and (2) reverse the drastic frequency changes imposed on the music signal in order to make LPs playable. If an LP were to be cut without treble pre-emphasis and bass pre-de-emphasis, the high treble would be lost, while the deep bass notes would cause the stylus to jump out of the groove.

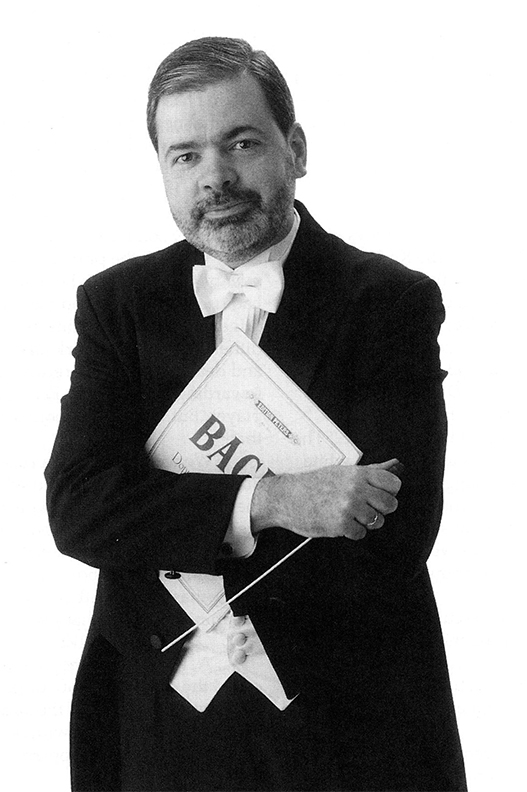

Berlin the Bear loves pre-RIAA LPs, especially if they are from Berlin. Photo by John Marks.

I went into the phono-equalization issue in general and at some length HERE. What is relevant to this discussion is that upon the commercialization of long-playing (hence, LP) microgroove phonograph records (from mid-1948), there was no generally-accepted standard for cutting equalization, and therefore no standard for playback equalization. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), established in 1952, promulgated its standard in 1954. However, adaptation was neither instantaneous nor universal. That was in part because of the Not Invented Here syndrome, and in part because 78-rpm discs kept selling, with the last US commercial 78 rpm made in 1959.

For many music lovers, whether an early (especially pre-stereophonic) non-RIAA LP plays back properly will be a non-issue. But music lovers who want the best fidelity from their early DG or Decca LPs will need more playback-EQ options than the usual phono stage provides. There are several phono stages made expressly for archival institutions, but prices on those units start at more than two thousand dollars, and run up to over ten thousand dollars. (There is, in theory, also the option of making a digital transfer of an uncorrected LP, and then handling playback EQ in the digital domain; however, at the time I was doing my product research, the least-expensive such "flat" phono stage was about $2500.)

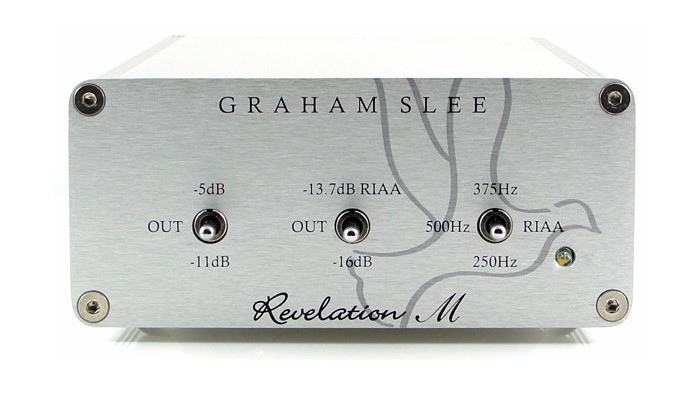

I searched high and low for an affordable (circa $1000) phono-stage playback solution that would handle all of: standard RIAA LP playback; the most prevalent non-RIAA early LPs; and the most prevalent electrically-recorded 78-rpm records. My search led me to the web site of audio designer Graham Slee. As explained on his website, Graham Slee's products are sold via an intriguing business model. In each market or country, a fan of the company maintains a (so to speak) library of demo units to be lent out to potential buyers. In the US, that chap is Bruce Kohl, himself an engineer. Bruce lent me the Graham Slee Revelation M phono stage for use with the Rega Planar 3 and its Elys 2 cartridge. ("M" standing for moving magnet; there is a moving-coil version as well.)

Note: Prices on that website are in UK pounds and include V.A.T. Further, US prices will change a bit over time with currency fluctuations. At the time of writing this, the Revelation M with basic power supply was about $840. Without opening up any political cans of worms, it does appear that that post-Brexit-vote fall of the UK Pound on currency markets has made Graham Slee's UK-priced gear considerable bargains in The Former Colonies. Bruce included the deluxe power supply unit, a circa-$200 option. So the Revelation M, the upgrade power supply, shipping, and estimated US customs duty at present total about $1200. (There are also a few US retail audio dealers who carry some products.)

The first thing to say is, playing back an RIAA LP, the Revelation M sounds just wonderful–engagingly lively, but never harsh or jittery. Smooth but detailed. I loved the sound! I was pleasantly surprised at the compliments my David Oistrakh Cleveland Brahms concerto LP rip received. Steve Daniels of The Sound Organisation (Rega's US importer) gets the prize for conciseness: "Wow."

So, Point No. 1: if you are looking for a plain-vanilla RIAA phono stage, I recommend you talk to Bruce Kohl about what Graham Slee can do for you at various price points. You can start that conversation by emailing me HERE. I will then put you and Bruce in touch with each other by email.

These days, good RIAA playback at many price tiers is a given (almost). However, the "Unique Selling Proposition" of the Revelation M is that its toggle switches allow for 12 different playback-EQ curves. (The Graham Slee website has information on which curves apply to different releases HERE.) To test that capability, I first made a digital transfer of the US Decca release (Decca Gold Label DX-141) of David Oistrakh's 1954 Mozart Violin Concerto No. 5 (with the Saxon State Orchestra (Dresden) under Franz Konwitschny) using the RIAA playback curve, and then a separate digital transfer using the proper Decca "ffrr" curve. ("ffrr" standing for "full frequency range recording.") For both excerpts, the analog-to-digital converter was from Sound Devices.

The difference between the RIAA and ffrr playback EQ curves is that the treble cut is 13.7 dB for the RIAA, but 11 dB for the ffrr .

2.7dB might not sound like a lot; but, what matters is the "area under the curve." I think the perceived difference is major, especially on a violin recording. Here are the two sound samples from this original monophonic LP from 1954.

Mozart Violin Concerto No. 5 (Movement 2, Adagio)

David Oistrakh, violin; Saxon State Orchestra (Dresden), Franz Konwitschny.

RIAA playback EQ.

Mozart Violin Concerto No. 5 (Movement 2, Adagio)

David Oistrakh, violin; Saxon State Orchestra (Dresden), Franz Konwitschny.

ffrr playback EQ.

Nerdery note: I am aware that the Decca LPs in this two-record set were cut from master tapes recorded by Deutsche Grammophon (or from a pre-EQ'ed DG LP-cutting master tape). However, my research indicates that in the early 1950s, DG's and Decca's playback curves were essentially identical.

To sum up: if you are an institutional archivist on a budget, or an audiophile who listens to pre-RIAA LPs (or who wants to digitize pre-RIAA LPs), Graham Slee's Revelation M is the best solution I have found. If it fits your needs, I recommend it most highly.