In the year 2002 the CD era was in full swing. CDs made up 93% of all recorded music sales—a huge slice of the pie. Vinyl record sales were 2/10ths of 1%. Into that vinyl-on-life-support environment Lamm Industries introduced their first phono preamplifier, the LP2.

Fast forward 17 years to 2019. Sales of all physical music media are down. From their lofty previous peak, sales of CDs—the "perfect sound forever" format—are now less than 6% of total recorded music sales. Vinyl sales rose from the near-dead to 4.5% of total sales. (Data from the RIAA. Used record sales not included.) The years 1973 through 2018 saw nearly $29 billion in new vinyl sales. Recent technology advances in record cleaning increase the viability of the medium; it's easier now to revive old records and preserve new ones.

Today, vinyl abides. Good standalone CD players are increasingly scarce, but 18 years since the arrival of the original Lamm LP2, its successor, the LP2.1, remains persistently in production.

Across those 18 years phono stage technology has not stood still. From support for multiple tonearms to variable impedance loading, from remote control to user adjustable equalization curves, modern high-end phono preamplifiers are feature-packed and bling-rich with user interfaces offering push buttons, dials, and touch screens. Lacking most of those extras that add convenient flexibility but also drive up price, the LP2.1 carries on. Can it survive in today's marketplace? Is it a viable choice in the face of modernity? Lamm Industries sent me a LP2.1 Deluxe version so I could gauge for myself.

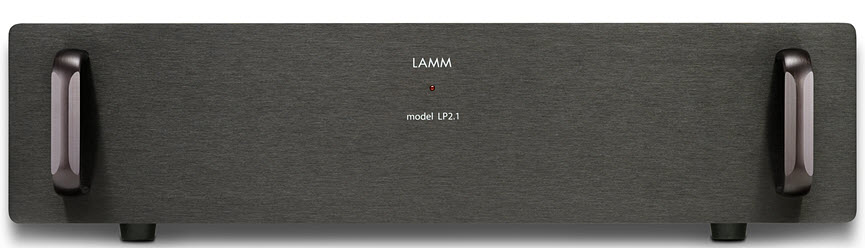

Outside its air-shipped wood crate, the LP2.1 Deluxe is a low-slung box measuring 4.5" high x 19" wide and 13.875" deep, plus rack mount handles. It is dense matte black, receding into my audio rack more like a stealthy Grumman skunkworks project than a shiny modern phono stage; only a tiny red LED centered on its faceplate gives it away.

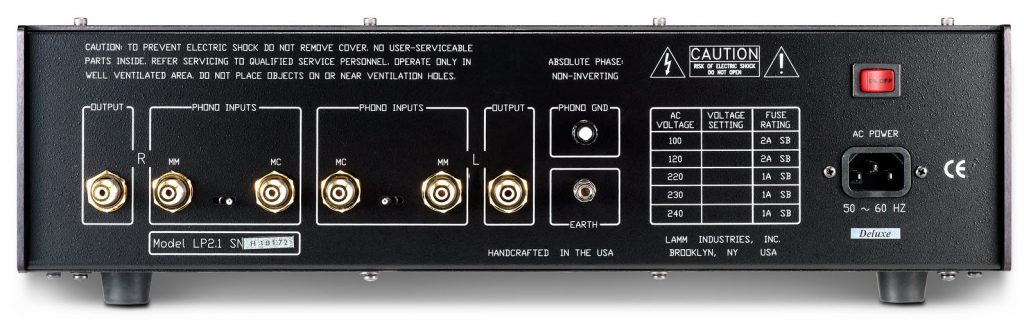

The rear of the LP2.1 tells you how simple it is to use. Connect your RCA terminated tonearm cable to either of the gold-plated Moving Coil or Moving Magnet inputs and flip two small switches to point at those chosen inputs. Connect output cables to the Left and Right RCA connectors to send signal to your linestage. Connect your tonearm's ground wire to the phono ground lug, plug in the power cable and flip a red on/off switch—you're ready to go. Output is muted for 45 seconds as the LP2.1's electronic protection circuity engages; that protection also applies if the unit experiences a drop in AC line voltage.

The Moving Magnet (MM) inputs of the LP2.1 send signal directly to the unit's first gain stage where it acquires 40dB of gain with a 47k Ohm input impedance and a low 20pF of capacitance.

The Moving Coil (MC) inputs provide an additional 20dB of gain by first sending signal through a pair of Jensen JT-44K-DX step-up transformers (1:10 turns ratio) and then to the first gain stage for a total gain of 60dB – input to output that's a gain factor of 1000. Lamm offers an option to replace the 20db gain transformers with ones offering 30dB gain; that option yields a unit total of 70dB.

The first question a phono stage buyer asks is: will this unit work with my cartridges? That depends very much on the cartridge's voltage output. My own general guideline has Moving Coil cartridges that deliver less than 0.3mv needing, at minimum, more than 60dB of gain. There is also the issue of noise: a low output cartridge run into a low gain phono stage can mean turning up linestage volume which may, depending on the linestage, increase background noise such as tube rush or record surface noise.

The impedance load of the LP2.1 is fixed, and its default value is 400 Ohms. Lamm Industries may be able to accommodate a different specific value—talk to you dealer. Look to your cartridge maker's specification—they'll usually give you an impedance loading range. When a phono stage's impedance is too high, sound may be thin with too much bite or emphasis, for example on higher frequency brass instruments. If the phono stage impedance is too low the sound may be darker or compressed. Lamm's choice of 400 Ohms is a reasonable value for an array of Moving Coils having (here I borrow from Fremer) an internal impedance of 40 Ohms or less.

There are two versions of the LP2.1, Standard ($13,090) and Deluxe ($13,390, reviewed here). The Deluxe version uses high quality polystyrene capacitors to bypass film capacitors in the signal path, and it offers greater power supply energy storage (150 joules) versus the standard unit (125 joules.) To help mitigate the impact of mechanical energy from external sources, the Deluxe version adds mass in the form of a damping plate attached to the bottom of the unit. That brings the Deluxe weight to a hefty 41.5 pounds versus the standard version's 22 pounds. Lamm claims the additional mass "leads to a slightly more extended, coherent, and natural bass reproduction."

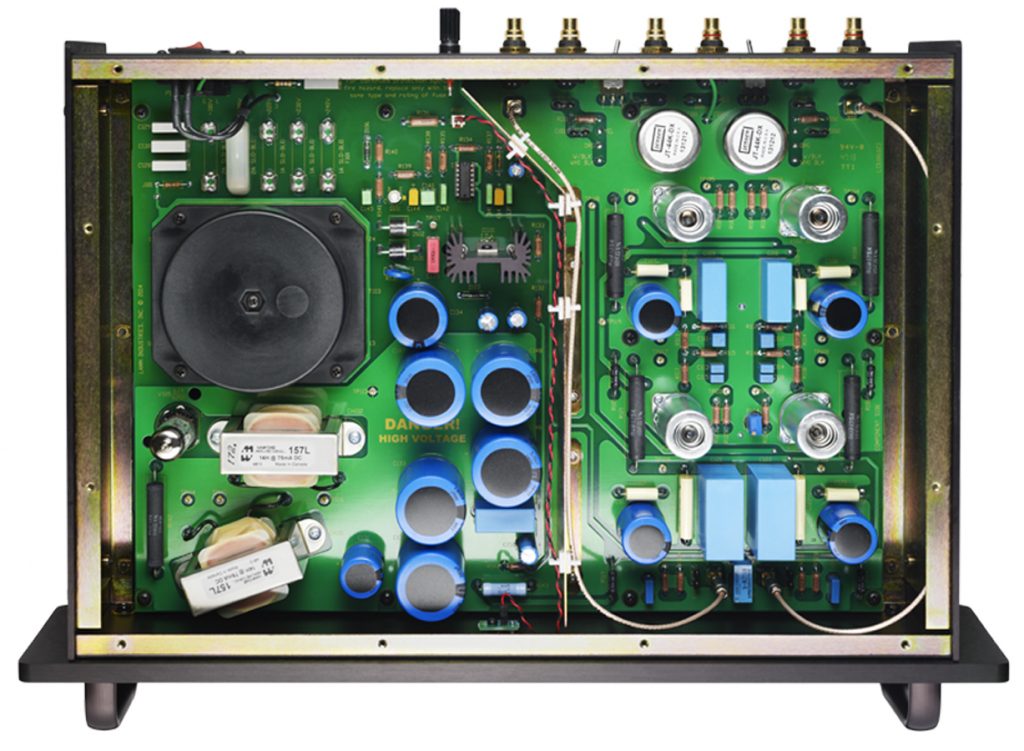

The LP2.1 operates in pure class A mode from input to output, and its dual-mono layout means excellent channel separation. It uses a no loop feedback circuit, drawing on a design that Lamm Industries uses in their single-ended ML2.2 and top-line ML3 power amplifiers. Tubes in the LP2.1 are the same as Lamm adopts for their reference LP1.1 Signature phono stage. The LP2.1's first amplification stage uses matched pairs of the Russian 6C3P (6C3P) and the second gain stage takes matched 6C45P-Es, (6C45P-E), one per channel. I've seen these tubes nowhere else but in Lamm equipment; count on buying replacements directly from them.

With a single exception (a Pass Labs XONO) I've always used a tubed preamp or phono stage in my system. One challenge is minimizing the sound of tube rush and avoiding microphonic tubes. Once introduced, such noise will persist through downstream amplification. I found no such issue with the LP2.1. It is easily one of the quietest, lowest noise tube phono stages I've tried. That quiet operation is not by accident. The high-transconductance tubes chosen for the LP2.1 are low in noise and microphonics. The added damping mass of the Deluxe edition helps reduce noise.

Vladimir Lamm observes that a power supply is an integral part of the signal path. Full-wave vacuum tube rectification (6x4 tube) in the power supply is followed by choke-containing filters to reduce any hum or buzz from the already low-noise custom-designed Plitron power transformer. Voltage rails to amplification circuitry are dual mono, each with its own Pi filter to reduce AC ripples on the DC signal and further reduce noise.

An accurate passive RIAA equalization circuit sits between the LP2.1's first and second gain stage. Across the full audio spectrum (20Hz to 20kHz) Lamm specifies equalization error at less than 0.5dB. Per the specs, plenty of headroom is available: 250mv for MM and 25mv for MC. Output impedance is 2.8KOhms. Lamm claims the phono stage will "drive any cable and any reasonable real world load."

For many audiophiles, specifications don't often tell us about the unique sound of a component. But, understanding how a circuit designer arrives at his product can say a lot about its overall character. Does the designer have a particular sound or a set of goals that guide him? Does he build a prototype, ask listeners to react to it, and then adjust things based on what they say? Understanding the methodology used in a component's construction can tell us a lot.

Vladimir Lamm was an orchestral percussionist, and to this day remains first a music lover and fervent listener. He is also an engineer and a scientist with a university background in solid-state physics and semiconductor design. His audio designs derive from his systematic research into psychoacoustics undertaken while working in the Soviet military-industrial complex as Chief Design Engineer of Research and Development at the Lvov Radio & Electronics factory. There, Lamm had plenty of resources and pools of test subjects available to him for conducting hundreds of blind and double-blind listening experiments about what happens when people hear certain sounds, particularly the complex sounds of live music. Using empirical data gathered through listening tests, he formulated a mathematical model to describe what he calls "the human hearing mechanism." He turned that model into electro-mechanical models implemented as specific circuit topologies.

From further testing with human listeners, many of whom were musicians and performers, Lamm discovered that only a very few circuit topologies suit the human physiology. Regardless of electronic properties and distortion specifications, as humans we perceive sound in a certain way. A successful design must be congruent with the rules of human hearing. The LP2.1's electronic design follows from Lamm's codification of countless hours of real world testing, which enabled him to create equipment with predefined and predictable parameters, and eliminated the need for a trial-and-error approach to designing his products; he will tell you it is based on the way we hear with the ears we have. "As humans," Lamm observes, "we are created in a certain way. We perceive sound on various levels as well as subconscious or intuitive. We perceive sound not just with our ears, but with the whole body." Thus, Lamm will answer the question about why the LP2.1's design has not changed in many years: "Its foundation in how humans perceive sound remains unchanged."

Along with its sonic character, which we'll get to in a moment, the long term viability of the LP2.1 also comes from its quality construction, stable operation and Lamm's focus on high reliability. A brief look at its interior reveals a tidy organized layout. Parts are chosen for long term dependability and minimal sonic signature: Vishay resistors, Roederstein film capacitors, RCD wire wound resistors, and Electrocube polystyrene capacitors that parallel Vishay film caps—these are some of the names you'll see inside. Each part is checked, transistors are matched to 1%, and vacuum tubes are tested prior to installation. Lamm's parts acceptance rate is typically 1 out of 3. In the following interior picture you can see a steel wall separating the power supply (left) from the amplifier section. A flexible organization of fuses in the upper left allow the LP2.1 to work on any of the world's voltages. Shielded cables carry signal to the RCA outputs.

Lamm brought to his American audio company the same component-based modular construction techniques and industrial-level build methodologies found in military grade equipment. High reliability is at the fore. The LP2.1 uses high-quality printed circuit boards. Each module is burnt-in and tested for two hours continuous operation before assembly; another round of testing and measurements follows. Each completed unit then burns in for 72 hours. The LP2.1 comes with a 3-year warranty.

I won't walk through all the LP2.1's specifications. It's worth noting the company Web site provides thorough documented specifications, among the best in the industry.

Review Context

During the LP2.1's break-in period—I gave it 150 hours—I used a 10" Tri-Planar mk.VII with a Lyra Etna cartridge (0.56mv). I also used a van den Hul Colibri Master Signature (1.1mv) cut down to fit on my Tri-Planar 'arm. Normally I won't use an expensive cartridge to break in a component, but that cartridge was new and I wanted some hours on it. For the majority of review time I used a different vdH Master Signature or a Fuuga cartridge mounted on the latest Kuzma 11" 4Point tonearm. The tonearms mounted on a Grand Prix Audio Monaco 2.0 direct-drive turntable sitting on the top shelf of a Silent Running Audio Scuttle rack.

I used the 0.35mv output Fuuga into the LP2.1's Moving Coil transformer input with its 60dB total gain. I'm not skittish about turning up the volume on a linestage; the Fuuga performed fine with linestage volume control well past noon.

The 1.1mv output of the van den Hul Master Signature is atypically high for a Moving Coil cartridge. When run into the LP2.1's MC input, the number of volume steps available on a linestage is significantly limited. I tried the Master Sig into the LP2.1's Moving Magnet input, by-passing the Jensen transformers, for a total gain of 40dB along with 47KOhms input impedance, which is within the accepted range specified by vdH for that cartridge. I can tell you the signature of the Jensen's is miniscule, difficult to detect with A/B/A listening. I did not detect extraneous sparkle or brightness with the wide open load. Only with much focused listening—closer to the speakers (which I don't normally do) did I hear the 1.1mv Master Sig through the Moving Magnet input with maybe slightly more detail, maybe a bit more dynamic articulation. I did not get a sense there was more musical drive running through the transformers versus not.

Linestages on hand were a couple of two-box units: the Audio Research Reference 10 ($33k) and the Lamm L2.1 Reference ($27,990, future review). Along with the LP2.1 I used an ARC Reference 10 Phono ($33k). Amplification came from my long term standard the Lamm M1.2 Reference monoblocks ($33,990). Signal cable was Shunyata Sigma, power cords were stock and speakers were Wilson Audio Alexia Series 2.

Sound

When you close your eyes in the concert hall do you sense vivid three-dimensional images of performers and instruments? In your mind's ear are there precisely delineated rows of violins playing or musicians laid out in bas relief? Does your seating offer "illumination of the furthest corners of the soundstage?" My experience largely finds such effects not in concert halls but in listening rooms, where electronics along with room factors and speaker positioning help produce them. In the concert hall do you hear "velvety black backgrounds?" Do transients "pop like fireworks against a night sky?" Many audiophiles like these sonic characteristics and reviewers do write about them as the quotes (taken from real reviews) suggest. To my ears they are audiophile "virtues," psycho-acoustic idealizations of the live experience. What do you want your stereo system to sound like? I use live music as my reference.

If a key to understanding the Lamm LP2.1 is familiarity with the research, modeling, and design that took Vladimir Lamm to its implementation, a key to appreciating how it sounds is to experience live acoustic music. Before he built prototypes, Lamm the empiricist, the scientist, derived his mathematical models from human hearing, from listeners' exposure to real music, not to stereo systems. To gauge the LP2.1 for yourself, go to a concert hall before you go to an audio show.

I'm not saying that the LP2.1 transforms your audio system into a concert hall or you cannot distinguish it from live music, but the Lamm unit does not overreach the acoustic music experience by exaggerating or highlighting certain musical characteristics the way some modern audio components do. So often we reviewers choose the previous model component as an evaluation reference rather than the musical source.

The overall character of the LP2.1 is modest and somewhat difficult to describe in audiophile terms. It lays so little character of its own upon a recording. Nonetheless, every audio component has its signature. My approach is to describe what I hear.

What the Lamm LP2.1 offers is a sound that is affinitive with what I hear from live acoustic music. But I never mistook it for more than an ingredient in the reproduction chain. My initial reaction to the unit was not "there's more of this and less of that"—my ears simply took to it straightaway, like wearing my favorite jeans or sitting in a comfy chair.

The LP2.1 does a fine job of portraying the ambience and context on a recording of a large orchestral performance, a soloist on a stage, a quartet in a church, or a jazz group in a small venue. It lays out the soundstage well. On some recordings I had a greater sense of energy in the venue than I did dimensional depth. Back and side wall reflections are rendered appropriate to the recording, but without drawing attention. And yet, whether it is the complex harmonic mist hovering above a section of massed strings, or vibrations bouncing around inside a cello's resonance chamber, this Lamm phono stage is capable of realistic "you are there" moments. I sensed the sound of performers and the sound of their venue together. The Lamm's perspective is less granular and more of the whole.

The Lamm LP2.1 is a big picture phono stage. It does not have an analytical cast that pulls perception into audiophilic focus on this or that sonic feature. Its sound is integrative, holistic, if you will. Holistic—that's a rather fuzzy word—it reflects my listening experience as more than a bundle of audiophile adjectives. Consider this: if you break a piece of music into brief phrases, the basic elements are dynamics, timing, and tonality. Take any of those away and the phrase is gone. The sound of the LP2.1 does not encourage doing this. Its focus is the whole musical presentation, which is no focus at all. But… audiophiles, or at least we reviewers, seem fated to analysis. If you take your listening mind out of the moment, if you break the gestalt and intentionally look at pieces, you'll find they are there.

The orchestration for Aaron Copland's "Fanfare for the Common Man" (Telarc, 10078) includes 4 horns, 3 B-flat trumpets, 3 trombones, 1 tuba, a bass drum, timpani and a tam-tam—all and only brass and percussion, the traditional elements of a fanfare. Let's analyze the sound coming from the music's first measures. In the first two bars, the tam-tam (likely an orchestral-sized brass Chau gong) receives a single strike at double forte and a second strike at forte. The idea is to get your attention and, believe me, it does—big whacks at a big gong.

With the LP2.1 in place, both strikes of the tam-tam filled the entire front of my listening room with a massive brassy bloom and then, as its sound developed further, a wee touch of metallic brass "tizz." The giant gong's harmonics flowed outward, a diaspora of sound waves rippled from a point, like a still pond hit with a big drop of water. Without the gong being struck again, this resonance continued on its own for the entirety of the next three bars. Simultaneous with the first tam-tam strike, percussionists struck the timpani and bass drum repeatedly in unison with double forte force. Copland's score notes say "very deliberate." I could tell the bass drum was a big one hit with a soft mallet. I heard an attack against its skin but more so a "push," the movement of a large mass of air; the low bass sound was full and deep. At the same time a hard mallet attack on lower register timpani skins tuned to F (~87Hz) and B-flat (~116Hz) was tonally obvious but almost consumed inside the massive whumpf of the bass drum. Those opening bars yielded a sound of unquestionable mid-to-lower bass authority and heft. Perhaps even more impressive was the low frequency tonal density and differentiated pitch through the Lamm phono stage.

The timpani and bass drum strikes continued through the third and fourth measure. The score to Fanfare shows the entire fifth bar as pure silence; the musicians stopped. Copland's instruction says, "Let it vibrate." When it's on the recording with the venue at hand, the LP2.1 excelled at conveying a sense of sound in space. The tam-tam (not struck since the second measure) continued its outward blossom. I sat mesmerized, as if I were inside the large acoustic space of Atlanta Symphony Hall, the orchestra unmoving. Across the four beats of that fifth measure time seemed to slow, the once vigorous tonal energy from three percussion instruments spreading, fading, and gradually dying away.

Out of that dying resonance a solo trumpet emerged with the iconic theme. Transients from high octave trumpets present a challenge for any phono stage, particularly those with less than adequate power supply reserves. With its 150 Joules of energy storage, the LP2.1 Deluxe never flinched. The highest note typically scored for a trumpet in orchestral music is a B-flat, near 1 kHz, almost two octaves above middle-C. Fanfare contains several instances of that high note. From the opening solo and throughout the performance, the LP2.1 fed by the Colibri Master Signature—a cartridge capable of excellent top-end energy—rendered trumpets as direct, clear, and pure, the archetype of brassy sound with a whisper of golden sweetness. I heard the trumpet's opening solo without thinness, forward piercing, or harshness on the leading edge. That's not to say the LP2.1 rounds off the initial attack; rather it revealed the strength of the performer's breath, embouchure, and skill at launching the note. From lows to highs, the LP2.1 let this Fanfare for the Common Man come alive.

On first hearing it took maybe five seconds to realize Ellington Indigos (Impex/Columbia 8053) is a superb album—perfect for late night listening. This 1958 recording features the polished, cultivated sound of a swinging jazz orchestra honed to a perfection of synchronized precision, the kind that comes from playing together nightly as the group toured cities across America.

The soundstage is broad and layered with Duke Ellington's piano at center stage, faultlessly mic'd, its top open wide. I heard that unique piano sound of hammers striking strings, resounding within the piano's chamber and off its lid. Ellington's touch is simply wonderful—to my ears no one in jazz comes close to his nuance with the ivories. He can play softly at so many levels while gently emphasizing certain keys, giving evidence to the LP2.1's facility for both a fine micro-dynamic gradient and rich tonality. Particularly in the lows and mid-bass, this phonostage lets you hear the initial strike that sets the pitch, the sustain and then decay with no thinning or loss of harmonics.

The LP2.1 is wholly capable of delivering an instrument's sound according to the varying recording contexts from album to album. If you've ever sat near someone playing a grand piano you know the sound up close is more complex, more resonant than twenty feet away. Here, those complex harmonics were very much in evidence. The piano's single string bass notes and multi-string mids and highs were defined and very realistic. As Ellington turned notes into chords and phrases with both left and right hands, shifting the music's center away from and then back to consonance, the LP2.1's tonal rightness—its density and weight—was among the most realistic I've heard. Occasionally I heard the mechanical sound of Ellington's pedal press and I could easily tell when he used either the damper or the sustain pedal.

On the tune "Tenderly," Jimmy Hamilton's closely mic'd clarinet, in solo or duet with Ellington, sounded as a live column of air. Having played the instrument myself I know that the LP2.1 revealed its tone as neither warm nor cool; it had that magical lit-from-within character with no sense of producer applied reverberation. Saxophones had a bit of added reverb, but that did not take away from hearing the breathy altos or that wet reedy grunt from the baritone. I heard the defined pluck of stand-up bass strings yet the production did not over-emphasize them. Gentle metal brushes on cymbals sounded with swirly texture. Across the orchestra it was easy to modulate my focus, catching slight dynamic shifts and subtle note-bendings from sections and individuals while taking in the precise syncopation of the whole group playing together. Their music flowed so easily, rising and falling. The band sat in an acoustic space defined by its own boundaries with little to no back or side wall reflection, yet within the group there was plenty of air and energy and its overall scale seemed just right. Together, this album, the Colibri Master Signature and the LP2.1 evinced a delightful synergy.

These analytic-critical listening descriptions may not be the way to appreciate music, but they expose how the LP2.1 together with the rest of my system responded sonically to the signal coming off the cartridge. Leading edge transients could be ever ever so slightly relaxed compared to high-contrast units, but the Lamm always sounded with vivacity, never dull or rounded. I sensed no homogenizing effect as attack intensity or relative sharpness varied with the record and performers on hand. The LP2.1 may show a slight emphasis in the low-midrange through mid-bass that accounts for the unit's capacity for rich timbral shading, but it never sounded thick, or sentimental. If you're looking for a warmish presentation, this may not be the phono stage for you.

Listening to complex music with high pitched sounds from the likes of harps or glockenspiels on the perimeter of the orchestra (positioned further away from the microphones) the LP2.1 may not be the final word in tippy-top-end extension—that's in terms of amplitude not frequency. It is not as naked or transparent as, say, an OTL preamp, yet the LP2.1 has such a low noise floor that I never found clarity wanting. You'll need to spend more on a different model or brand of phono stage—a lot more—to achieve the LP2.1's level of tonal rightness, dynamic grip and articulation. It's easy to nit-pick with words. Maybe I'm casting about for something to criticize. Listen first to what you hear from live acoustic music, and then assess. In essence this Lamm phono stage brings little notice to itself while raising the bar for downstream components. Like a nice day, the LP2.1 charmed me. It helped draw me into music, into a relaxed state where I stopped taking notes, stopped thinking about my system and simply enjoyed the flow.

Listening to complex large scale classical music through this Lamm phono stage does not disappoint. On big orchestral works, my suspension of disbelief requires solid, articulate mid-to-low bass along with a sense of space, scale and perspective—a sense of an orchestra laid out in a hall. Dynamics, timing and tonal character must hold together across the frequencies. The system must offer coherent resolution across orchestral peaks and shifts.

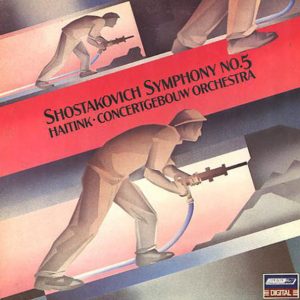

Some Western critics consider Dimitri Shostakovich's 5th Symphony to be his answer to Pravda's (Stalin's) condemnation of an earlier composition. Having written it at age 30, the composer characterized the 5th as a "narrative representation of a hero's life and death." It is more lyrical and psychological, less styptic but, at times, no less raucous than some of his other works. It won him praise and a reprieve, perhaps saving his career as a Soviet composer.

When the needle dropped on a performance from Bernard Haitink and the Concertgebouw Orchestra (London LDR 71051), the LP2.1 did nothing to hide that album's digital origin. The recording was made in 1982 at the start of the CD era. From the outset of my listening I sensed it as overlaid with a very fine grained patina of nervousness. Regardless, Haitink has things well in hand; the performance was nicely balanced and its sound clear.

At the outset, I heard hall resonance increase as violin sections increased their volume, not so much in terms of back wall reflections but greater harmonic energy and shimmer, filling the air around them. Playing ostinato, low-end strings set a backdrop for melody and themes. I heard the basses and cellos as sections, the sound of their rosiny bows moving, churning with ebb and flow, yet never as one large instrument. Subtle dynamic and timing changes spoke of a collection of individuals playing together. Inventive composers keep their rhythm sections busy with interesting lines and phrases while undergirding higher register interest. The LP2.1had no problem parsing these meaty bass lines handed off between sections at different pitch. Plucked notes from strings were firm and distinct. Mallet strikes on bells had a crisp metallic ring without glare. Horns bloomed, trombones growled, sharp trumpet attacks bit into notes without shriek or hardness.

The composer is so adept at building low frequency tension and foreboding, then suddenly breaking into a riff of sweetness and light for a few bars, catching the listener off guard with its beauty. I heard violins hold a single shimmery high note, very high at pianissimo volume, as the background for a brief duet between a harp in its upper octave and a flute in its mids. The LP2.1 caught the delicacy of this music just right, evincing its easy pace and the exquisite timbral and textural differences between the instruments. Detail was plentiful as I heard the flute as breathy, rounded with excellent timbre, along with each distinct pluck of the harp resonate into gossamer wisp. In the far left corner, background bells repeated upward moving arpeggios; very light in touch, yet with every note audibly clear.

The Fourth Movement of Symphony 5 is fantastic—its upbeat martial character obvious at the finale—although some critics find its optimism a bit feigned, bending to the orthodoxy of Stalin's will. From a reflective Third Movement, themes shift as the Fourth opens with a high energy swagger. Bam, bam, bam comes the attack from timpani with weight and solidity, and it was easy to hear their heads resonate undamped. There is no doubt about the LP2.1's capacity for defined low-end heft on timpani and other instruments with even lower pitch. What I heard told me this phono stage is capable of dynamic thrust and punch. With raspy trombones, upper octave trumpets, percussion and basses going full tilt I heard no distortion on dynamic peaks as the sound did not falter in the face of full symphonic demands. The Lamm unit captured the music's quick dynamic gradients, step by step upward. In my mind's ear the orchestra laid out before me as a shifting carpet of sonic texture. It yielded a coherent soundstage that escaped the 11-foot distance between my Alexia 2 loudspeakers, and filled the full 16-foot width of my listening room.

A brief contrast with the Audio Research Reference 10 Phono

The Ref Phono 10 (RP10) is a $33k two box (control unit and power supply) phono stage that is the current top-of-the-line model from Audio Research. Normally I like to discuss differences between the review subject and a unit in the same economic ballpark, but that's not happening here. If you think this is "unfair," well okay.

Listening to the 45rpm 2 LP reissue of Blood Sweat & Tears' album of the same name (ORG 133), the sonic differences between the two phono stages were easy to hear. With both high and low voltage transformers and amplifier-level capacitance, the RP10 presented leading edge transients as more sharply defined than the LP2.1 while demonstrating greater overall dynamic contrast. This was particularly evident on bass guitar and percussion. Although both units had plenty of mid-to-low bass depth and weight, the RP10 sounded faster with greater punch and authority. Listening to Hammond Leslies rotating in their cabinets on "Spinning Wheel" (and having played a Hammond B3 with Leslies) I found the LP2.1's tonality more lifelike and harmonically right, whereas the ARC unit sounded ever so slightly lighter and thinner. David Clayton Thomas' voice had a richer more realistic tone through the LP2.1, although it sounded more articulate with slightly more detail through the RP10.

Both phono stages were very quiet. On Dorati's Firebird (Mercury/Classic Records SR90226) the RP10 offered a greater sense of dimensionality, making back and sidewall reflections and overall depth more evident. Spaciousness is a hallmark of the Audio Research sound. Instrument separation and outline definition were in higher contrast through the RP10—more so than I hear live in concert. The LP2.1 had slightly better center-fill. Through the ARC unit glockenspiel and strings playing pizzicato were finely taut with occasional front-of-note edge, while its upper-mids and highs could, in contrast, sound a wee bit silvery in character. I'm drawing contrasts here; don't underestimate the RP10 as a highly resolving component.

Conclusion

Vladimir Lamm likes to say the perfect audio review consists of a single word that defines the component. Obviously I needed more than one. But if forced to pick one word to describe the LP2.1, my word is: believable.

Unassuming in appearance and straightforward in features, the Lamm LP2.1 evokes the natural sound of live acoustic music. Its capacity for tonal rightness and harmonic complexity makes it a standout performer. It is neutral in character while easily revealing differences in cartridges and performances. It doesn't try to draw attention to itself and it is not high-contrast hi-fi. This is a listener's component, a musician's component. It consistently drew me in to each performance.

Although its feature set flies under the radar, its sonic performance competes with or betters any phono stage I've heard under $20k. The review unit functioned flawlessly throughout my time with it.

Lamm LP2.1 phono stage

Retail: Standard version: $13,090 (USD)

Retail: Deluxe version: $13,390 (USD)

Lamm Industries, Inc.

2513 East 21 Street

Brooklyn, NY 11235

USA

718.368.0181