"Black" Background – Roger Skoff writes about what it's really like.

Have you ever been to the beach? No, I'm not kidding. There really are millions of people—unlike us here in California or on either coast—who live nowhere a major body of water, and whose only idea of the beach comes from movies.

So, for those people, let me try to describe at least one aspect of the beach going experience—waves.

As you stand on the beach and look toward the expanse of the water—any body of water big enough to have waves—you notice that the waves come in, peak as the top of the water continues at speed but the bottom is slowed by the land beneath them, curl over, form whitecaps, and crash to the sand, only to withdraw to form again as the next wave comes in. And you notice that the whole process has a rhythm—a regular ebb and flow as the waves come in almost perfectly spaced in time.

That's the obvious part; the other part, equally important, is farther out from the beach—the more or less smooth-looking surface of the water where the waves are being formed, preparatory to coming in to the shore. There, although the water may seem anything from near-glassy smooth to peaked with countless visible wavelets, is where the real action is, and where all of the waves come from.

Consider this: water is a near-perfect carrier of energy, and—as can easily be seen in any (large or largeish) container—a bathtub or swimming pool, for example—any energy applied (throwing a rock in, stirring it with your hand, or whatever else), water will be moved, will form a wave, the wave will continue until it hits the side of the container, will bounce… and will keep on doing the same thing, forming more and more waves of diminishing energy, crossing each other, interacting, and creating new, smaller waves, until the entire surface of the container is covered with waves so small that you can't see them (the so-called "glassy-looking" surface) and still keeps moving until all of the energy has finally been entirely dissipated.

And that finally get us to the subject of this article, "The Myth of the Black Background."

I would tell you that the sound we hear is analogous to waves in water, but that would at least be an understatement: the sound we hear is exactly the same as waves in water. Sound is created when energy is applied to something—vocal cords, a musical instrument, one car crashing into another, a leaf stirring, or an entire symphony orchestra—to create a vibration, which causes a medium (for us, usually air, but anything that passes sound will do) to carry it forward until it dissipates.

And, just like water in a closed container (consider the ocean a big container), whenever the transmitted energy hits a "wall" or any other obstruction it bounces and keeps on bouncing, creating more and more waves (echoes to, finally, "nano-echoes") until the energy is dissipated and "gone."

And that leads, really to two subjects, room acoustics, which we'll deal with another time, and "the space between the instruments."

In a concert hall, a movie soundstage, a recording studio, a stadium, or on the street (where on a holiday, a marching band might be going by as part of a parade), or even in your listening room— anywhere at all that music is likely to be playing—what we have, sonically, is the same as that contained volume of water mentioned earlier:

There's not just an empty volume of air with one or more sound sources in it (performers, instruments, or speakers). Unless it's the world's best anechoic chamber (an-echoic = no echoes) there's the sound (pressure waves in an air medium) made in the current instant and also the sound of every past instant, reverberating, filling the medium with reflected (bounced) energy off every surface of everything in or that creates that volume.

In short, when your system is good enough that, when it's playing a symphony orchestra performing in one of the world great concert halls and you can hear not just that there are violins, but how many there are; how far apart they are; in how many rows; and where the string section is placed within the hall and in relation to all of the other instruments, you shouldn't hear silence or a "black background" to the music: The air between the instruments, like the "glassy-smooth-looking" water in the ocean, is alive with energy: The sound of this violin, of all of the others, of all of the other instruments, and of every bounce of every sound made by every performer and every instrument, off every wall, every person, every instrument, the venue's floor and ceiling and everything else possible since the first instant when the orchestra started playing and until all of the sonic energy has either been absorbed or otherwise dissipated.

That's what you'd hear in real life, and it's what your system ought to be playing for you, instead of some phony "black background!"

Is a black background really what you want? It is possible: In sound, as in nature, black is not a color; it's the absence of color. It's darkness instead of light. What I'd rather have is something nobody ever talks about—a white background, where white is, as in light and, I would imagine, in sound too, the presence of all colors. That's what I would hope to hear from my system and certainly what I would get in a concert hall.

If you really want a black background for your music, though, it's easy—especially in the digital realm: Just set your system so that nothing at all below a certain volume level or bit count will be played.

Your background—the surround for what you do hear—will be totally "black" and you will have filtered out all of the low-level information that gives music its character and "life." You'll also have filtered out all but the most obvious of the locational and soundstaging information—for me, HiFi's greatest joy.

Go for it, if you want, but it's not for me; I'd rather keep a black background a myth.

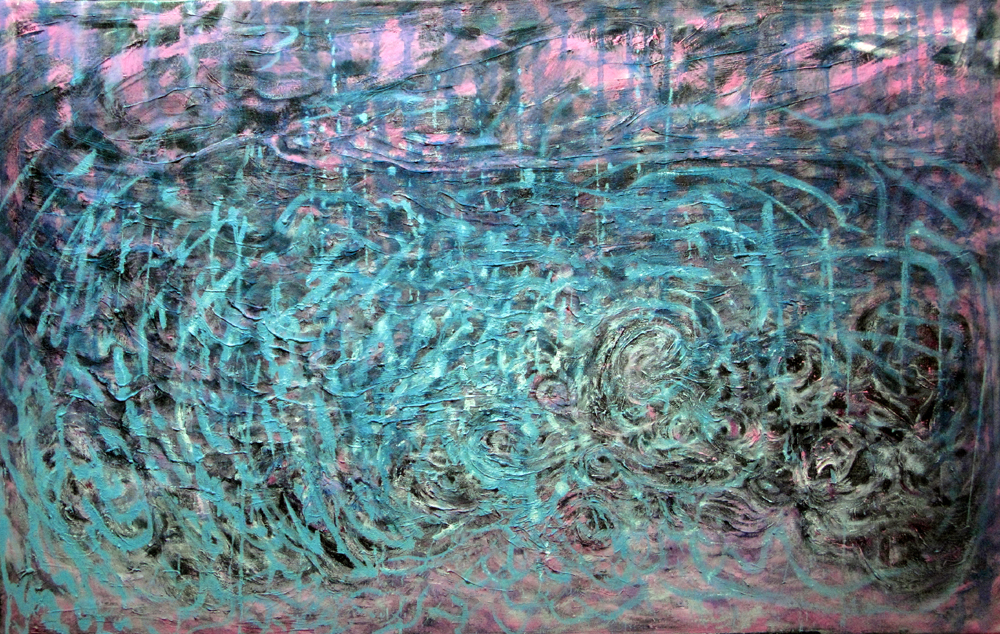

Painting and drawings by Dan Zimmerman.