The great Trini Lopez (1937-2020) was a superb guitarist and singer. He was also an actor, both on film and on TV. The talented musician, who also hung with the Rat Pack, was born and raised in the Little Mexico neighborhood of Dallas, Texas. He started playing rock 'n' roll at age fifteen, and the first time he entered a recording studio was in 1957. As proven by his earliest recordings and by his mild-mannered studio albums from the mid sixties, Lopez created his best music before live audiences. In his early years of performing, he caught the attention of fellow Texan Buddy Holly. In 1957, Holly arranged for Lopez and his group The Big Beats to make recordings at Norman Petty's famous recording studio in Clovis, New Mexico. That same year, again with Holly's help, Lopez signed a contract with Columbia to issue records from the Clovis sessions. The result was the release of one 45 single, and then suddenly, according to Lopez in the documentary My Name is Lopez, the other two members of his band decided that they no longer wanted to have a Mexican as their leader. Disappointed to say the very least, Lopez parted ways with The Big Beats and signed a new contract with Cincinnati's King Records. With help from studio musicians, he cranked out more than a dozen singles for King, but he experienced little in the way of success, so on he went searching for better opportunities

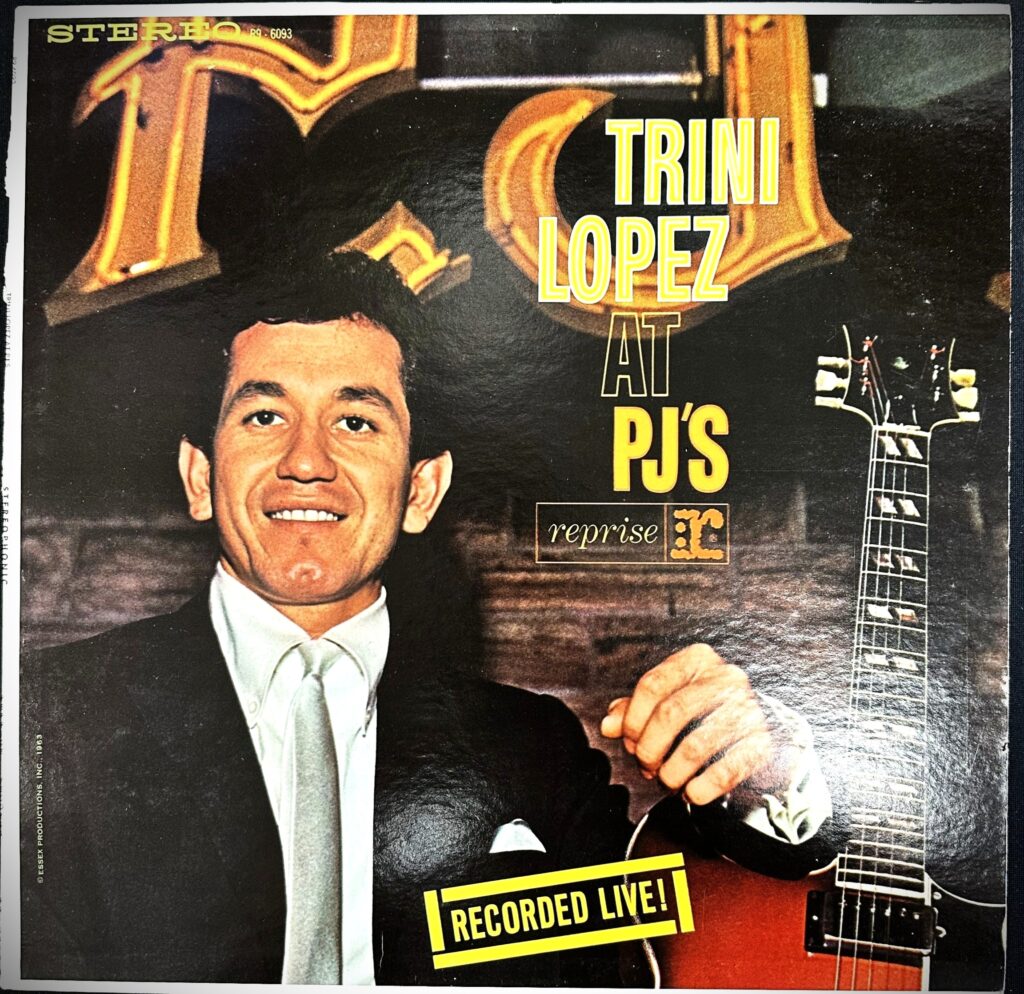

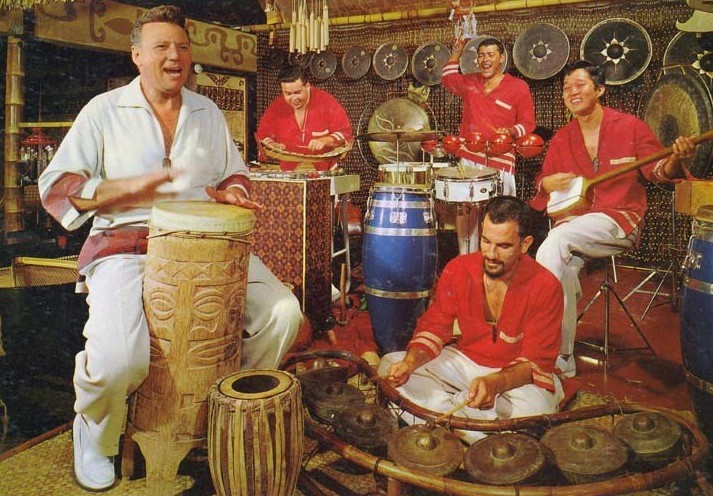

At the behest of fellow Dallasite Snuff Garrett, Lopez relocated to Los Angeles in 1960. Best known for producing Bobby Vee and Gary Lewis & The Playboys, Garrett, a former Lubbuck DJ, who also knew Buddy Holly, was searching for a new frontman for Holly's band, The Crickets. With few auditions and the project going nowhere, Lopez left Garrett and The Crickets. In need of work, he found employment at a lounge in Beverly Hills called Ye Little Club, and a short time later at P. J.'s nightclub in West Hollywood. After gaining a following as a solo act, he asked P.J.'s owner for a raise. With a little more cash in his pocket, Lopez went looking for a drummer, and as luck would have it, he stumbled upon an incredibly good one, Mickey Jones (1941-2018). P.J.'s was a popular night spot for the Hollywood elite, and a man named Frank Sinatra took notice of him there. Sinatra signed Lopez to his record label, Reprise, and, soon, under the direction of producer Don Costa, an exciting and fast-selling debut album was released. In short order the world fell in love with Trini Lopez.

Although the seventies was the era of live rock albums, the early sixties were not. Lopez and Jones created a sensation at P.J.'s. The two—or three when they were joined by bassist Dick Shriver—shook the rafters and the place was regularly packed. Although Lopez wanted to make records in the studio, of which he would eventually make many, Sinatra witnessed something that his label sorely lacked, and he knew that the best way to get it was to record the electric guitar-playing Lopez in a live setting. Up to this point, Reprise had been a cocktail party, adult-friendly, music label where you wouldn't find this kind of excitement. The album Trini Lopez At PJ's (Reprise RS-6093) became the label's first record featuring rock 'n' roll. The album also became a worldwide smash hit, and spawned three successful singles, including the magnificent "If I Had a Hammer." Recorded by famed recording engineer Wally Heider (1922-1989), the album was released in 1963. In addition to its authentic sound quality, it featured the explosive energy that was happening between Lopez and Jones. This energy appealed not only to young record buyers, but also to the mature audiences that was Reprise's bread and butter. The record also inspired a slew of similar sounding live albums by Johnny Rivers, which also featured Jones on drums. Another effect of this record was the steady succession of recorded-live rock albums from the seventies. Deep Purple's Made In Japan, The Who's Live At Leeds, Frampton Comes Alive, Neil Diamond's Hot August Night, and The Allman Brothers' At Fillmore East are all part of the legacy that Lopez created.

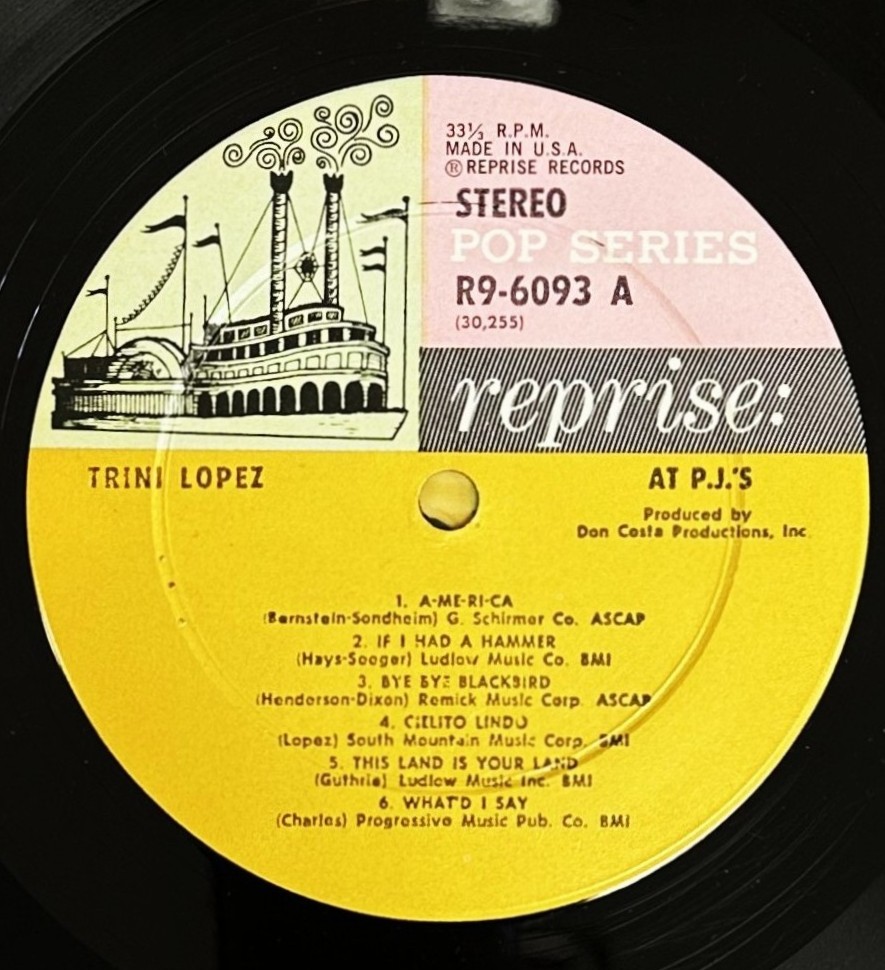

Before I get to the music on this record, it's worth noting that the setlist of the album isn't necessarily an actual setlist. I wish I could see a genuine P.J. 's setlist to see how many of the songs on the LP follow the same order. The last cut on side one, "What I say," was clearly taken from the end of a show, as Trini says "goodnight."

Side one of Trini Lopez At PJ's opens with the club's announcer enthusiastically shouting, "And now, P.J.'s proudly presents Trini Lopez!" The announcement is followed by a very danceable reworking of "America," from West Side Story. As the musical fireworks start, Trini asks "for a little hand clapping now," and does he ever get it! In addition to the audience's clapping in unison, is their singing voices joining Trini in the song's chorus. Mickey's drumming is insanely fine. Nobody ever struck the bell of a ride cymbal better than he could! His cymbal and tom-tom work is worth the price of admission, and so is Trini's loaded-with-Latin American-pride singing. The stereo sound, due to the minimal mic usage, provides the listener with the authentic sound of being inside a club. The music is so full of adrenaline that I find it difficult to describe the ever-growing gusts of musical energy. If you're playing this, hopefully nice and loud, and your body isn't moving, get some medical help!

And just when you think the music couldn't get any better, Trini hits you with another salvo. It's his reworking of The Weavers' "Hammer Song," known to everybody—after Peter Paul & Mary retitled and popularized it—as "If I Had a Hammer." Written by Pete Seeger and Lee Hayes in 1949, in Trini's hands it became the happiest protest song ever created, or better said: one of the happiest records ever recorded, which just happened to be a protest song. Much different than The Weavers or Peter, Paul, and Mary, the lyrics still meant everything they did before, but now the song had a swinging beat. As music lovers, and, of course, as audiophiles, we love the harmonies and the acoustic guitar magic of The Weavers and Peter, Paul, and Mary, but we don't dance to their music. We just lower our moving coils onto their records and listen to the clarity of their blended voices, the guitars, and the impressive soundstage. When Trini came along, he noticed that the song needed his secret blend of Mexican spices, and when he added them the song exploded! Even as I sit here in my office, typing my thoughts and sipping coffee, I feel compelled to warm up my eight KT88s and party my brains out to this song.

I always skip cuts three and four. Every pop record seems to have weak moments, and that's why we have cuing levers and skip buttons. Did Trini really go from rocking our souls and inventing folk-rock with "If I Had a Hammer" to a family-friendly singalong of "Bye Bye Blackbird?" The answer is yes, so I lifted my tonearm and moved over to the next cut, which is a singalong performance of "Cielito Lindo." Not my cup of tea. Time for the next cut.

Cut five is a return to what makes this album great. Trini had an affinity for folk music, and he shows it on "This Land Is Your Land" with the same gusto which made "If I Had A Hammer" a masterpiece. Mickey is again a vital part of the music's magic. His ability to punctuate the beat was second to none. And, just like in the opening cut, hearing the audience singing is a pleasure.

Cut six is a driving performance of Ray Charles' "What I Say." You can feel the intensity in the room as Trini opens with the famous piano riff on his electric guitar. The interplay between the band members is mind-blowing. Not to be outdone is Mickey, whose drumming is controlled and explosive at the same time. It's a tragedy that neither Sinatra nor Costa didn't have the show filmed. To make up for the lack of visual excitement, I found this similar performance from The Ed Sullivan Show (HERE). Yes, it features some offstage brass, and the guys are jamming a little longer, but otherwise the approach to the song is the same. I also recommend the version found on Trini's Live At Basin Street East (Reprise RS-6134), as it's just as exciting, and a little longer.

Side two opens with that most famous Spanish language rock 'n' roll songs, "La Bamba." As we're all accustomed to Ritchie Valens' version, the first thing you might notice is that Trini sings it a little faster. Trini's history with "La Bamba" goes back to his childhood. Like Valens, Trini wanted to create a rock 'n' roll version of the ancient Mexican folk song, but Valens beat him to it. I like Trini's version just a wee bit better, mostly because I love his voice, and because I'm hooked on Jones' drumming.

The second cut is the Mexican folk song "Granada." Trini's voice is magnificent, but the song has the worst sound on the album, making it disappointing. Then there's the third cut, a medley consisting of "Gotta Travel On," "Down By The Riverside," "Marianne," and "When The Saints Go Marching In." The sound is good, and the drums sound great, but I would have preferred hearing my favorite of the three songs, "Gotta Travel On," in an extended performance on its own.

Side two closes with an exciting performance of Ray Charles' "Unchain My Heart," and it sounds like it came from the same session that provided us the first two cuts on side one. The energy from side one has returned, and Mickey is the star of the cut. His kick drum and cymbals sound fantastic. A little treat for us audiophiles: His kick drum packs a nice solid punch.

One thing that became apparent after spending an entire week of indulging myself in all things Trini Lopez: He was a seriously good guitarist. Although he mostly strummed his lead guitar, his sound was assertive and appealing. As I became engulfed by his music, I wanted to learn about his equipment. When Trini recorded this record, his electric guitar was a Gibson Barney Kessel. After the success of the album, he worked with Gibson on creating a new guitar. The result was actually three guitars, the Trini Lopez Standard, the Trini Lopez Deluxe, and in 1968 Gibson issued the Trini Lopez Custom. From that point on, if Trini was seen with an electric guitar, it was one that bore his name. I can hardly stop myself from gazing at the Trini Lopez guitar. With its diamond shaped f-holes, it is gorgeous, especially in red! As shown by this short video on YouTube (HERE), Dave Grohl also loves the Lopez guitar in red. He also loves how it feels and sounds, as he played his 1967 Trini Lopez guitar on all of the Foo Fighters albums.

I was hoping that I could find out what guitar amp is heard on this album, but there is no available information on that. Although Lopez owned a 12 watt Fender Princeton Reverb, which was auctioned in 2021, the only photo that exists from an unspecified date at P.J.'s shows him playing his Barney Kessel through an 80-watt Fender Showman. The bigger amp does seem more appropriate for club usage, right?

I can't write this review without giving Mickey Jones his own paragraph. After approximately three years with Trini, Mickey went to work for Johnny Rivers, and a little later he worked with Kenny Rogers in The First Edition. Jones' cymbal crashes on "Secret Agent Man" never fail to blow my percussion-loving mind, but so does his perfect shuffle beat on "Ruby, Don't Take Your Love To Town." As Levon Helm of The Hawks opted out of Bob Dylan's 1966 world tour, Jones was Dylan's top choice replacement. And it was during the tour that Dylan started referring to his backup band as The Band. So, in a sense, you could say that Mickey Jones was The Band's first drummer! Jones was also an accomplished actor, often seen on TV shows, such as Tim Allen's Home Improvement. He acted in many films. You might remember him as Billy Bob Thornton's drummer in Sling Blade.

In the eighties, when good quality used records were plentiful in thrift shops, yard sales, and church rummage sales, I bought countless copies of Trini Lopez At PJ's. Over time, I discovered that no two copies ever sounded the same. I currently own three pristine copies, and they all have A-1/B-1 matrix numbers. However, they do not sound alike. Only one of my copies is demo-worthy on side one, while all of my side twos sound pretty much the same. It helps if you play this record with a fast moving coil, like my current tonearm resident, a heavily modified Denon 103R from Paradox Pulse. The album's rich balance allows you to play it loud without listener fatigue. And when you play it loud, the drums and Trini's voice sound excellent. Although Trini's voice is close mic'd, he's also coming from a PA system, so, yes, there's a little bit of PA coloration on his voice. This isn't bothersome. As the recording was made, according to Trini, over a period of two or three nights, the sound varies from cut to cut. I hear many variations in Wally Heider's mic placement. There's also what I refer to as the "tale of the missing bass player." As I stated above, Trini and Mickey sometimes worked without a bass player, and I think that's the case on some of the songs here. One of my listening projects was to listen very carefully to hear a bass player was present on every cut. On some cuts, I could hear a bass line, while on others the bassist is either missing or so far from the mic that you can't hear him. Funny, unless you're actively searching for the bass player, it's unimportant if you hear him or not. Trini and Mickey played like a perfect machine with or without a bassist.

So there you have it. Trini Lopez At PJ's isn't perfect. Most records aren't. However, the best cuts on the record make the album a must-have title. It's also an historical album: It gives the listener a chance to hear the birth of folk-rock, it's groundbreaking in terms of on-location rock recording, and it's the debut album by an artist who bridged a special gap between adult pop and rock 'n' roll. Also important is how Trini Lopez opened the door—and our ears—for Latin American pop musicians, such as Tony Orlando, Vikki Carr, and Carlos Santana. If you've been passing by this album in the used bins, it's time to grab your own copy. History was made at PJ's, and you can be part of it.