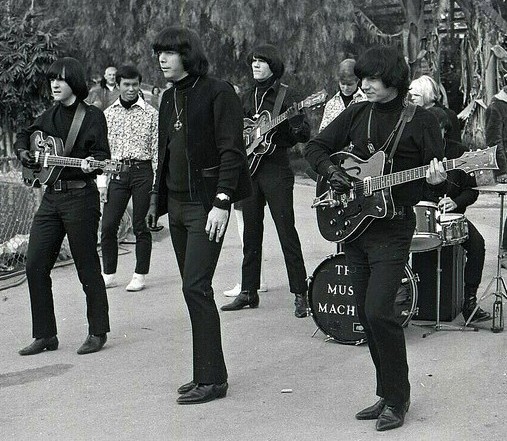

With the exception of a few songs by The Ramones, I dislike punk rock. However, I love punk-like songs from the sixties, the music that some experts now call proto-punk. Examples include The Kinks' "You Really Got Me" and "All The Day and All of the Night," The Who's "My Generation," and The Sonics' "The Witch." In addition to their aggressive style, another thing these songs have in common is they were singles which were later placed into mediocre albums. Mid-sixties rock albums tended to be shoddy. They were mostly slapped together by shirt-and-tie execs who just wanted something ready for the Christmas shopping season. In other words, something with an eye-catching cover that could be sold for more than ninety nine cents! Prior to the Doors' first album, and the Rolling Stones' Aftermath, The Beatles were unique in their ability to create strong albums. Having said all of this, there was a band from Los Angeles, who dressed in matching black clothes, wore matching black gloves, dyed their hair black, and made music that was aggressive, spooky, and sophisticated. And they, meaning the actual musicians, also created a great debut album in 1966 when most bands were struggling to produce two sides of a seven inch single. The band was The Music Machine, and the album was Turn On The Music Machine (Original Sound LPS 8875). Some historians call them proto-punk, while others call them a garage band, or both. To me, they were simply a unique band who created one great album.

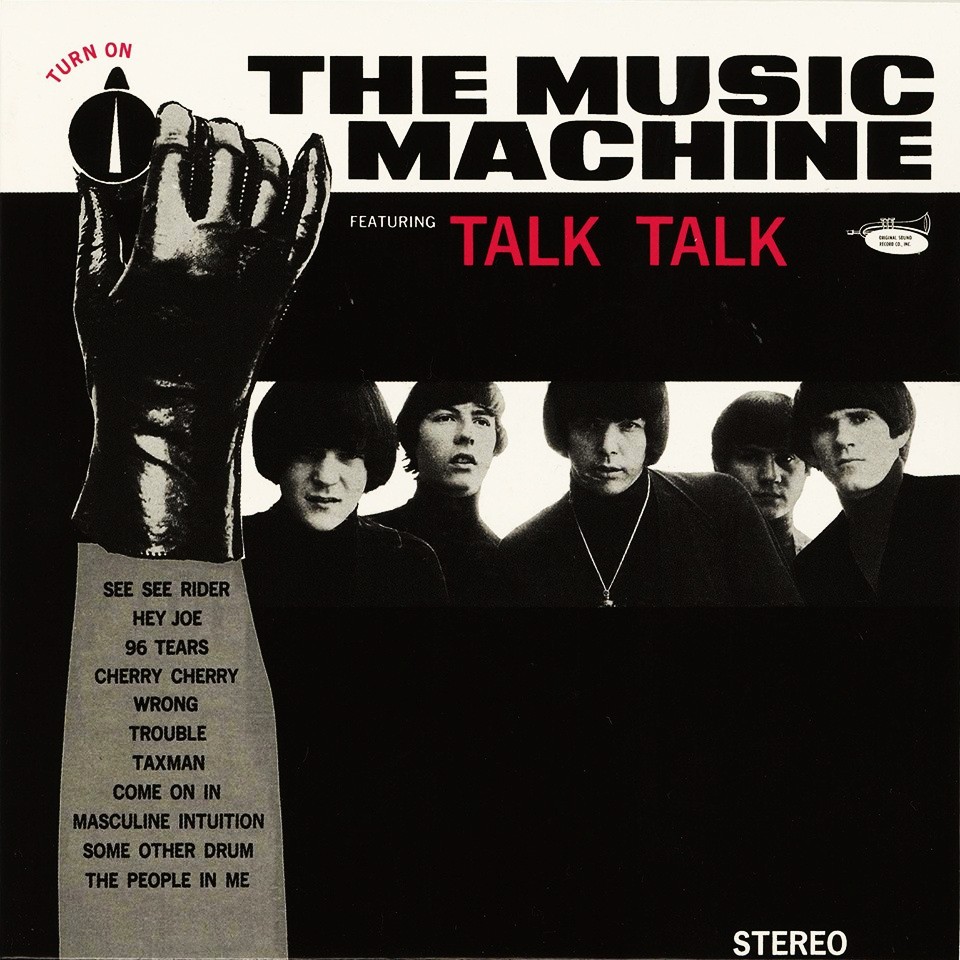

Before I tell you about the album, I'm going to tell you how I discovered it. The first time I saw the iconic album jacket was in a used record store in 1979. All I knew from this band was their hit, "Talk Talk," but for $1.99 buying the album was a no-brainer. It was also a stereo copy, and all that remains of it today is the jacket. The record was so scratched and filthy that I'm amazed that I played it, but persevered I did, through loads of surface noise and inner-groove distortion. In the process I fell in love with it. Some time in the mid-nineties, long after I discarded the trashed record, I found it on a CD (Performance Records Perf 397) and that's what I'm reviewing. And, by the way, the sound quality is excellent. And when I say excellent, I'm referring to an undoctored transfer of a mid-sixties master tape. The sound isn't squeaky clean, like a Steely Dan album, nor does it have a glistening soundstage like Love Over Gold, or subterranean bass, like Dark Side Of the Moon. Instead, it has a vintage all-tube sound that you can practically touch. More recently, it's been reissued with the mono and stereo mixes together on one CD. It can also be streamed in undoctored stereo.

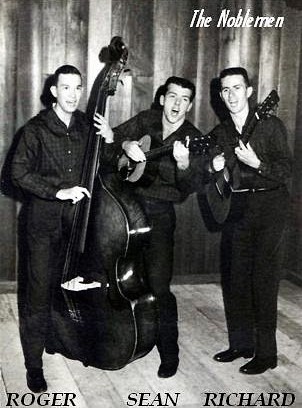

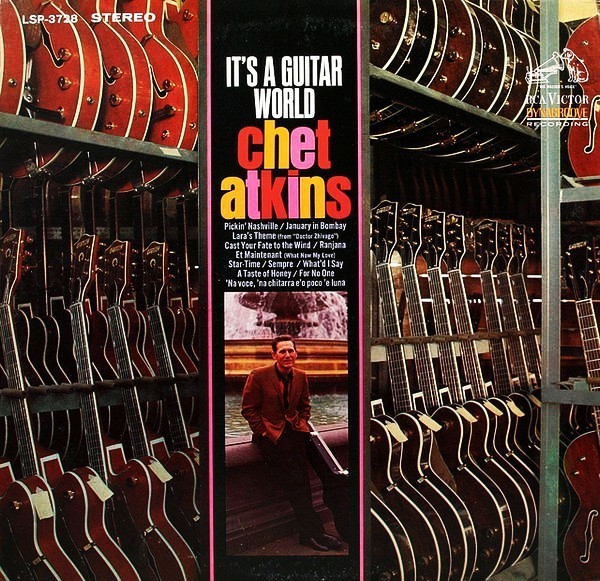

The Music Machine, originally The Raggamuffins, were formed in 1965, and their leader was folk-musician-turned-rock-n-roll shamen Sean Bonniwell (1940-2011). Bonniwell, the very definition of a cult artist, wrote all of the original material on this album, and I'm pretty sure he wrote all of the band's second and final album. The album also has five great covers. If you collect folk records, his name might be familiar. He was a member of a folk quartet called The Wayfarers who made three albums for RCA. Come Along With the Wayfarers (LSP 2666) was their debut from 1963. In the eighties, the album used to sell for one dollar and you could find it wherever used records were sold. I found my copy at my local Salvation Army in the mid-eighties. Seeing Bonniwell's name on a stereo copy (this time in good condition) made it another no-brainer. Unfortunately, the material was sappy and the sound was mediocre, so I didn't keep it. I did, however, keep their superior third album, a live recording called At the World's Fair (LSP 2966). Before The Wayfarers, Bonniwell was in a folk trio called The Noblemen. They never released a record.

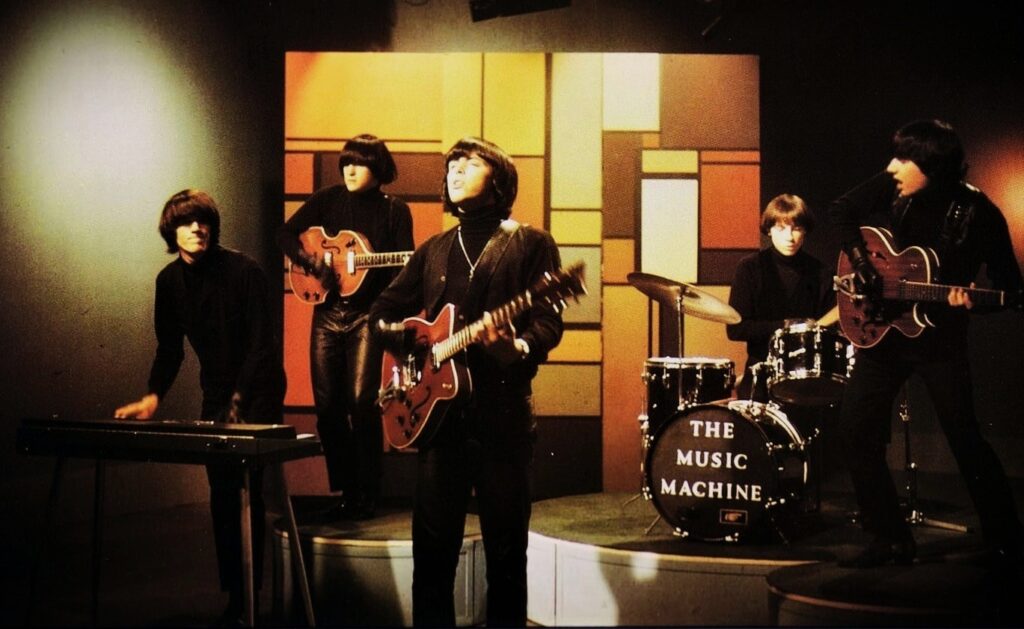

The members of The Music Machine were Bonniwell on rhythm guitar and lead vocals, Mark Landon on lead guitar, Doug Rhodes on keyboards, tambourine, and backing vocals, Keith Olson (1945-2020) on bass and backing vocals, and Ron Edgar (1945-2015) on drums. You might know Grammy Award winner Olson's name. He engineered and produced albums by Fleetwood Mac, Pat Benatar, The Grateful Dead, Santana, Foreigner, and Ozzy Osborne, just to name a few. Olson, who built The Music Machine's fuzz boxes, was also a folk musician. He played standup bass with singer Gale Garnett before joining The Music Machine.

The album opens with Bonniwell's best-known song "Talk Talk." The song describes the crumbling of a young man's world because his child was born out of wedlock. The bleak lyrics include "I know it serves me right / But I can't sleep at night / I have to hide my face / Or go some other place." And the lyrics that always stick in my mind: "My social life's a dud / My name is really mud / I'm up to here in lies / I guess I'm down to size." The powerful lyrics are matched by powerful musicianship. Here's a breakdown: It opens with explosive bursts from Rhodes' organ, and tom tom rolls from Edgar. This is quickly followed by more blasts from the organ, a cymbal crash, a slice from the highhat, and Olson's fuzz bass. The explosive intro comes out of the left speaker, setting the mood for what quickly comes out of the right speaker: Bonniwell's frenzied singing. At thirty seconds, also on the right, Olson's fuzz bass returns. At fifty-four seconds, again on the right, is Landon's power-packed lead guitar. At one minute, an aggressively played tambourine also appears on the right, effectively adding more agitation to the agitated mood. In short, this slightly-less-than-two-minutes song packs one of the hardest rock ‘n' punches ever captured on analog tape. The stereo mix, like many intended-to-be-released-in-mono singles from its era, sounds a little crude. The hard left/hard right stereo imagery is sonically akin to the first two albums by The Beatles. I'm a sucker for this sound, but I'm sure the mono mix sounds a little more cohesive. The rest of the album is stereophonically better, and Bonniwell's voice is placed where most people like it: in the center.

The second cut is Bonniwell's "Trouble." Just when you think the music couldn't smack you any harder than the first cut, "Trouble" will blow your mind to smithereens. It brilliantly picks up where "Talk Talk" left off. The lyrics deal with a Bonniwell specialty: mental trauma. He was a troubled soul. He left the music scene in 1969, and wrote a tell-all book in 1996, but more on that later. "Trouble" starts with a powerful buildup that lasts a mere two seconds. A big part of the buildup is Rhodes' ominous organ, which is also heard throughout the song. Landon's lead fuzz guitar is a big part of the song's appeal, and so is Edgar's impactful drumming. The incredibly tight musicianship is something you need to hear, along with Bonniewell's frantic singing. This amphetamine-laced song will make your body twist in ways you didn't think were possible. Do yourself a favor when you play it. Play it loud. And when I say loud, I mean your-neighbors-can-hear-it loud!

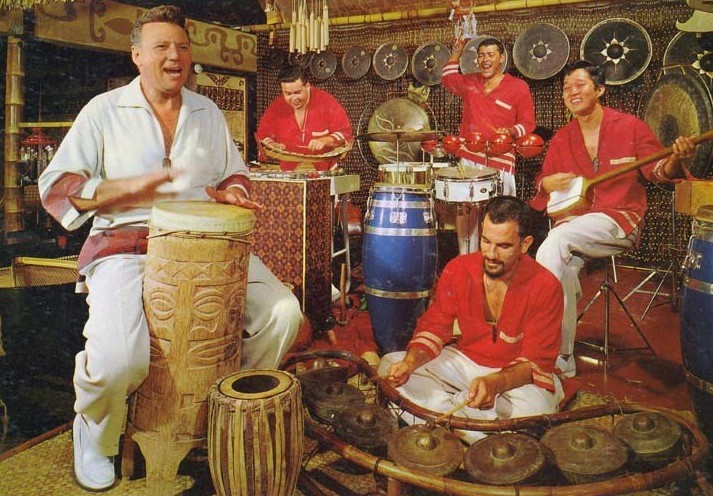

Cut three lacks the urgency that's typical of this band's music. It's a reimagining of Neil Diamond's "Cherry, Cherry." Instead of rocking the house down, Bonniwell and company went for a Caribbean sound, and added a flute. It's quite a stretch, but they pulled it off. I'd love to know who the flutist was, but the information is unavailable. It would be an awesome anecdote if the flutist was jazz legend Bud Shank. A year earlier, Shank played the flute on The Mamas & the Papas' "California Dreaming," so it's not impossible. Bonniwell's melodic singing harkens back to his time with The Wayfarers, and the vocal harmonies remind me of The Association. Olson plays an excellent fuzz bass solo which reminds us that they still had the capacity to rock. In short, this is a weird experiment that works.

Cut four is George Harrison's "Taxman." Some artists successfully reimagined The Beatles' songs into their own masterpieces. Examples include Joe Cocker's definitive version of "With a Little Help From My Friends," Stevie Wonder's socially conscious interpretation of "We Can Work It Out," and Sergio Mendes' very danceable reworkings of "Day Tripper" and "The Fool on the Hill." The Music Machine didn't reimagine "Taxman," but like Aerosmith's straight ahead recording of "Come Together," they performed an enjoyable no-surprises performance of a beloved song. It's a head-on assault with two groovy fuzzed-out guitars. This is the only cut where Bonniwell didn't sing the lead vocal. The unidentified lead singer sounds like a teenager from a high school choir, but the band's musicianship makes up for that.

Cut five is Bonniwell's "Some Other Drum." It's the only unplugged cut on the album. Some might see it as bubblegum filler. And that's how I hear it, but I love it anyway. Now that I'm older and a bit wiser, I noticed that parts of the song resemble The Lovin' Spoonful's "Did You Ever Have to Make Up Your Mind," recorded a year earlier. Another similarity to John Sebastian's song is the double-tracked lead vocal. Additional overdubs include a piano, finger cymbals, and an acoustic lead guitar. The song is proof that the innocent folksinger was still a lingering part of Bonniwell's persona.

Cut seven, "The People In Me," is my favorite cut. Bonniwell succeeded in writing one of most power breakup songs ever created, and right now I can't think of a better one. The words "When you see the people in me/Minus you/What will you do" will echo in your head when the album is over. It's menacing, haunting, and mesmerizing. It's also balls-to-the-wall rock ‘n' roll. And holy intermodulation distortion, Batman, Landon's fuzzbox is going to explode! Not to be outdone by Landon is Bonniwell's intense singing, and Edgar's impressive drumming. And like a plush carpet under everything is Olson's super ripe electric bass. If you're not playing air guitar, pounding on air drums, and not playing it freakin' loud, your local morgue has a table waiting for you.

Cut eight is a cover of The Animals' "CC Rider." It's my favorite cover song on the album, and it's also my second favorite cut. "CC Rider," originally "See See Rider Blues," was first recorded by Ma Rainey (1886-1939) in 1925. She also wrote the song, but her record sounds nothing like the rock classic. This seems to be a pattern with rock songs based on old blues records, and I cite Cream's cover of Skip James' "I'm So Glad" as another example. I could have described it as The Music Machine's interpretation of a song that's been covered by many artists. However, their template is the single by The Animals. And I learned it from The Animals, but as much as I love them, I haven't felt the desire to play their version since I discovered The Music Machine. And it's not because Bonniwell sings better than Eric Burdon (that would be impossible); they just play it so much better! Compare the two for yourself. With Edgar's viciously pounded skins, Rhodes' pumping organ (it's a Farfisa organ), and Landon's screaming lead guitar, you won't find a better performance of this song anywhere. You can practically see the sweat rolling down Bonniwell's face while he sings. If your foot isn't tapping to the beat, seek medical help. And, by the way, this isn't a Haydn string quartet, so honor the band with some respect. Crank it up!

Cut nine, "Wrong," is a frantic song about being wrong, when you thought for sure you were right. We've all eaten crow, but as adults we learn and move on. But Bonniwell wasn't one to surrender. He knows he's wrong, and he's having such a tough time dealing with it that he wrote a song. In this song he turns that crushed feeling into rage. His lyrics, his maniacal singing, the menacing backup vocals, and the band's frantic playing creates a rip-roaring flood of emotion. And the energy is so powerful that you won't be able to resist it! Rhodes' pulsating organ, Landon's fast guitar playing, and Edgar's ever-intense drumming add fuel to Bonniwell's utter madness. Noteworthy is Rhodes' masterful tambourine playing. (The Tambourine had to be an overdub, but you'd never know it.) If your listening chair lacks a seatbelt, hold onto it tightly!

Cut ten is a great performance of "96 Tears." It would be impossible to improve upon the original by ? (Question Mark) And The Mysterians, but hearing it performed by The Music Machine is a blast. They open the song with a short introduction of their own. A stark contrast to the the original is the use of a fuzz guitar and a fuzz bass. The original relied heavily on Frank Rodriguez's Vox Continental organ, while Rhodes' used his Farfisa. The original featured the tenor voice of Rudy Martinez, while The Music Machine has Bonniwell's baritone. All of these factors contribute to an appealing but different flavor of the classic song. Thanks to The Music Machine, you can have 192 tears instead of the old 96! The stereo imagery is fantastic: The instruments are beautifully focused. During the intro Olson's bass bass on the left, but quickly he's panned to the middle. The drums are also on the left, Bonniwell's voice and the organ share the middle, and the lead guitar is on the right.

Cut twelve, the closing cut, is a uniquely slow and brooding version of "Hey Joe." What will be interesting to some is that The Music Machine released their slow "Hey Joe" eight months prior to the release of The Jimi Hendrix Experience's debut album, Are You Experienced?. Prior to these two recordings, "Hey Joe" was traditionally a fast song; The best examples are the recordings by The Leaves and Love. In the mid-sixties, recording "Hey Joe" was a rite of passage for American garage bands. The Music Machine's slow tempo was a break from normality, and to my ears they lack some of the magic that makes the Hendrix version more enjoyable. But I've heard more versions than I care to count, so I'm guessing that readers will love it. It's really spooky.

The Music Machine were ahead of their local competition in one area: Their tight musicianship. The Byrds were better at vocal harmonies, and their collective songwriting provided us with timeless songs, although it took them a few albums to create them. And until their fifth album, they were sloppy musicians. Prior to The Doors, the only Los Angeles band in my record collection that featured the musical chops of The Music Machine was Love. But Love's talent was crumbling by their second album. And by their third album, the celebrated Forever Changes, they needed help from studio musicians, like bassist Carole Kaye and drummer Hal Blaine. Turn On The Music Machine didn't require outside help.

I couldn't help but wonder what Mark Landon did after leaving The Music Machine in 1967. From 1969 to 1971 he was the touring guitarist for The Ike & Tina Turner Revue. However, despite his work for the dynamic duo, there is no evidence that he played on their records. Later, he became an Emmy Awarded makeup artist. His work includes The Young and the Restless and Roseanne. He is not related to actor Michael Landon.

Along with Landon, Doug Rhodes left The Music Machine after a promotional tour for their debut album. Bonniwell became too much of a control freak. He played in a number of bands, and he did some studio work. Here's an interesting piece of history: He played the celeste on The Association's "Cherish." In 1971, he moved to Victoria, British Columbia, and became involved in traditional jazz and klezmer music.

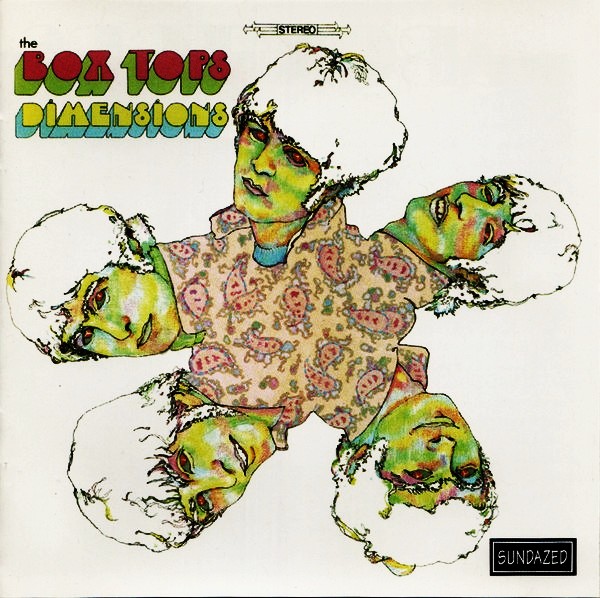

Articles about Bonniwell are becoming fewer as time goes on. This is sad. Prior to his death in 2011, his residence was a one room apartment in Visalia, California. I've had zero luck finding his book. Regarding the music he made after the band's debut, they or he (depending on your interpretation) released a second album in 1968, The Bonniwell Music Machine (Warner Brothers WS 1732). Part of the album features members of The Music Machine, while the rest features a different band. It's been reissued in various forms, including a Sundazed CD called Back To The Garage. On numerous occasions I've attempted to enjoy songs from the second album, and I failed every time. According to various sources, including Landon, Bonniwell penned enough songs to fill the debut album. Allegedly, their producer forced them to record covers. But were they forced to play those same covers on stage? I doubt it. I saw a setlist featuring the same covers they recorded. Also, I love the covers on the album, especially "CC Rider" and "96 Tears." I think the album would be inferior without them.

This is a great album heard as a whole. Here's some advice to my streaming friends: Let the whole thing play. Pour yourself some bourbon, or a cup of coffee, and swallow the whole thing. It's wonderful!