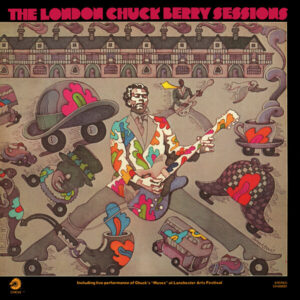

As one of the founding fathers of rock and roll, Chuck Berry (1926-2017) receives a ton of well-deserved respect as a musical innovator. Berry, along with Buddy Holly, was the first to define the image of the electric guitar-slinging rock star. However, despite his well-deserved status, the 1972 album, The London Chuck Berry Sessions (Chess CH60020) gets little fanfare. In the world of good albums, this one is mostly forgotten. Frankly speaking, the main reason I love this LP is because it's been a part of my life since I was thirteen. Although I am now somewhat critical of it, the music is permanently spliced to my DNA.

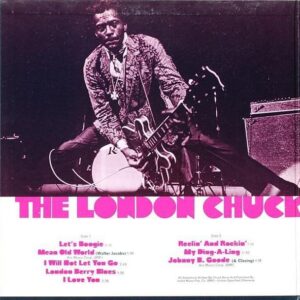

My interest in this album started when I received the single "My Ding-A-Ling" as a birthday present. Honestly, today the song sounds like the load of garbage that it always was, but when I was thirteen my ability to play a song wit h dirty lyrics was just plain cooler than cool. Returning to this album, thanks to a pristine first-metal (A/B) copy that I found in a thrift shop five years ago, reveals an imperfect but very decent album. When I was thirteen, pianist Ian McLagen (1945-2014) and drummer Kenny Jones were unknown to me, but today I know them as British rock royalty, and members of The Faces. Ian and Kenny are only on side one, as side two, the recorded-live side, features Owen McIntyre on piano and Robbie McIntosh on drums. These two men became famous as members of The Average White Band. Bassist Nic Potter is from the experimental band Vandergraft Generator.

Side one opens with a Berry original called "Let's Boogie." When I was a teenager, this kind of straight-ahead boogie made no sense to me. I was disturbed by its simplicity. Today, I love it for its simplicity, and I think it's the perfect way to open the album. Chuck's seat-of-the-pants guitar playing blends perfectly with the "sloppy perfection" provided by McLagen and Jones. The lyrics are weak, so what matters is the feeling, and the feeling tells me to crank it up! There were times when Chuck's voice sounded better, but it works fine on this cut. Again, it's the simplicity that makes the cut shine.

Cut four is one of the album's strongest moments. It's another Berry original, an instrumental called "London Berry Blues." Chuck's guitar playing sounds remarkably like Keith Richards', which is ironic, since Richards has spent most of his career sounding like Chuck Berry. Kenny Jones' drumming is to die for. If you loved Kenny's lyrical playing with The Faces, then this cut will be a special treat. Even when I was a teenager, when Jones was nothing but the drummer on side one, I heard something magical in his playing, and that magic is even stronger now that I can reproduce it so much better. I should add that this is the best sounding cut on the album, the only cut that I would use as a demo cut.

The live side, which is side two, opens with an old Berry original called "Reelin' And Rockin'." Even though Chuck recorded his original version in 1957, I prefer the matured version on this album. His voice is a bit ragged, but the stretched-out 7:07 minute version has a lot of great jamming to offer. A great bonus is the audience participation, and their rhythmic clapping is exactly what the song needed! Ironically, it is this 1972, albeit in edited form, that became the hit version. The original was the B-side of "Sweet Little Sixteen."

Side one cut two is "My Ding-A-Ling." One could call it a controversial song, due to its lyrical content. I'm perfectly comfortable calling it a pile of rubbish, although Chuck pulls a lot more life out of it than its composer, Dave Bartholomew (1918-2019), did in 1952. Eleven minutes and thirty three seconds is an awfully long time to endure such rubbish, but as a young teenager I loved every single minute of it. Unlike the original, Chuck turned it into an audience participation song. He coached the women to sing the word "my" and the men to sing "ding-a-ling." If you're new to the song, be my guest, and get right into it.

Cut three is the closing cut, and it's a supercharged performance of "Johnny B. Goode." I find it a true example of Chuck's talent that he could turn his 1958 classic into a genuine stadium rocker. I could go on and on, but all I want to say is crank this rocking mother up!

The ever important sound is quite good. As I stated above, the album only has one demo cut, but the likelihood of anybody grabbing this record for demo use is next to nil. On the other hand, I love the organic sound quality on side one, and the honesty of the live sound on side two. Nothing on the live side suggests any kind of post production reverb was used, and the use of reverb on side one is refreshingly minimal. In fact, the instrumental demo cut, "London Berry Blues," has no reverb at all!

I have to report that Universal's 180 gram reissue has one of the most beautiful jackets I've ever seen. The texture and the brighter colors make the original jackets look and feel boring. However, the reissue sounds like hell. It's absolutely dreadful. I swapped out my tired looking original jacket for the Universal jacket. However, most people lack my connections, and they would have to actually pay for the Universal reissue. However, if you really love this album you may want to consider the 180 gram reissue just for the jacket. My A/B original has the same exact sound that I remember from my teenage years. I found it amazing and wonderful that my EAR preamp and my Audio Research amplifier were able to take me right back to the moment when this music was fresh and on the radio. Let's face it, this has to be one of the best reasons to own a high end audio system. I have my speculation as to why the Universal 180 gram LP sounds bad. I'll bet the CD sounds a lot closer to the original LP.