The Flying Burrito Brothers were formed in 1968 by former members of The Byrds Chris Hillman and Gram Parsons (1946-1973), who both had similar backgrounds in rural music. Their debut album was the critically acclaimed The Gilded Palace Of Sin (A&M SP 4175), released in February of 1969. A few months prior to recording The Gilded Palace of Sin, Parsons, who was then the newest member of The Byrds, urged the band to embrace country music. The result was Sweetheart of the Rodeo (Columbia CS 9670), released in August of 1968. It was the mold from which The Flying Burrito Burrito Brothers were cast.

It goes against societal norms to mention The Flying Burrito Brothers without discussing Gram Parsons. The man was a good singer, and you can hear his singing on "You're Still On My Mind" and "I Like The Christian Life," both found on the Sweetheart of the Rodeo Legacy Edition CD. However, it is my assertion that his cult stardom is not driven by his music, Emmylou Harris, or his influence on The Byrds, but by the events surrounding his untimely death. The charismatic Parsons died at age twenty six from an overdose of tequila and morphine. It happened in a motel room in California's Mojave Desert, near where he wanted to be buried. This is indeed sad. However, the events following his death are downright creepy. After Parsons died, his body, which was at the airport to be flown to Metairie, Louisiana, for a proper burial, was stolen by his manager. And then the manager drove the coffin back out to the Mojave Desert and cremated Parsons by pouring gasoline in the coffin, and then igniting it. Nothing secures a rock musician's fame better than a drug overdose and an ignited coffin, right? One result of this is that Hillman, his friend, musical partner, and former roommate, has to deal with "Parsons mania" whenever he mentions Parsons' name in public. And I've seen the look on Hillman's face when it happens. Now that I've lifted this weight off my shoulders, the record I'm reviewing received no input from Parsons. The album is The Flying Burrito Brothers' third album, simply called The Flying Burrito Brothers (A&M SP 4295/Mobile Fidelity MFCD 772), released in June of 1971.

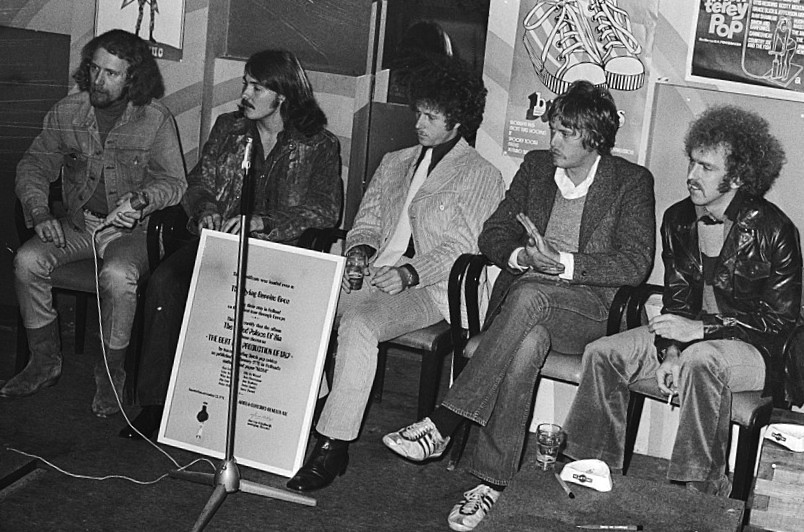

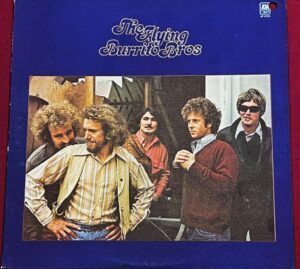

The short-lived version of the band that created the 1971 album The Flying Burrito Brothers was formed right after Chris Hillman fired Gram Parsons due to his unreliability and his alcohol and substance abuse. The new band consisted of Hillman on lead vocal and bass, Rick Roberts on lead vocal and rhythm guitar, Bernie Leadon on lead guitar and banjo, Pete Kleinow (1934-2007) on steel guitar, and original Byrds member Michael Clarke (1946-1993) on drums. If Rick Roberts' name sounds familiar, that's because you know him as the lead singer (along with Larry Burnett) of the hit-making band Firefall. Bernie Leadon should be a familiar name, since he's one of the founding members of the Eagles. Outside of the one and only Chris Hillman, the other holdover from the band's original lineup is Pete Kleinow (1934-2007), known best as Sneaky Pete. Also featured on this album is pianist Earl Ball. Folk legend Bob Gibson (1931-1996) played 12-string guitar on the song "Hand To Mouth."

Although I own a pristine pressing (M1/M1 metal) of the A&M LP, for decades I've preferred the convenience of Mobile Fidelity's CD. Sonically, it gives up nothing to the LP. Whoever performed the analog to digital mastering did so without any unneeded processing. Most analog master tapes, especially ones like this, don't need fixing as much as they just need to be faithfully transferred. And so I enjoyed hearing the Mobile Fidelity CD while writing this review.

The album opens with a remarkable reimagining of Merle Haggard's "White Line Fever." As much as I adore Haggard's incomparable baritone voice, this is one time where one of his songs needed someone else to make it work. And that person is Chris Hillman. (I urge readers to listen to both versions.) This three minutes and sixteen seconds piece of country magic begins with five descending notes from Bernie's lead guitar on the left. Two seconds later Earl Ball's piano enters on the right. Arriving simultaneously is Hillman's flawless voice, with a little bit of vocal help from Roberts. Hillman has had many fine vocal moments throughout his long career, but this one may very well be my favorite. Ball's piano playing is another vital ingredient to the song's magic. Michael Clark's drumming is restrained and poetic. As strange as it may sound, I've always felt the desire to play a cowbell along with this song. I'm pretty sure it's because I've always heard a quiet clank that sounds sort of like a cowbell emanating from the left side of the stage. I think it's Clark's cowbell, but I wouldn't swear by it. Again, I am completely lost inside Hillman's magnificent singing. It's easy to hear how much he loves this song. His voice sounds appropriately road-weary, a quality which, ironically, Haggard lacked on his original recording. The song's title suggests that it's about cocaine, but by all accounts it's not. It's a trucker's lament about loneliness on the road. Haggard's white lines are the lines on the highway, and the lyrics clearly convey the inescapable feeling of loneliness on the open road. However, as Haggard was no stranger to controlled substances, I can't help but wonder if the song was secretly about cocaine. Interpret it as you wish. John Lennon claimed that "Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds" was not about LSD, and Peter Yarrow insisted to his dying day that "Puff The Magic Dragon" was not about marijuana. As I hadn't played this album in years, I honestly wasn't sure if I still loved this song as much as I did in the past. Foolish me! Some of my old records haven't aged well, but the songs on this album are as strong as they ever were. Upon hearing "White Line Fever" afresh after all these years, I felt like I was hugging an old friend.

Cut two is the Rick Roberts song "Colorado." Rick was born in Florida, but he's lived in Boulder for most of his adult life. The song is a lament from a touring musician who misses his beautiful Colorado home and the lady he's left behind. I've tried for years to just let the song play, but I can't do it. It's just not for me, but critics have referred to it as one of the standout cuts on the album. Linda Ronstadt covered it on her album Don't Cry Now (Asylum SD 5054). I think she brought a teeny bit more to the table. Try them both and see what you think.

Cut three is the Roberts-Hillman song "Hand To Mouth." I love how this song thematically picks up where "White Line Fever" leaves off. The song starts soft and slow, but builds to an amazing climax and a jam session. The song is written from the point of view of a touring musician who is constantly living paycheck to paycheck, and, as the song says, is "never in one place too long." It opens with two beautifully strummed acoustic guitars and a double-tracked Hillman singing lead, with just a touch of Roberts in the background. The two are quickly greeted by some huge power chords from Earl Ball's piano. Ball's piano sounds like a dam that's ready to burst, and the dam bursts when Michael Clark's drums introduce the rest of the band at 0:54. I'm guessing that the song was originally an unplugged number intended for Hillman and Roberts and their guitars, since the only amplified instrument, Hillman's bass, could easily go unnoticed. The only thing missing is top-notch sound, which the rest of the album has. The sound isn't exactly bad, but it's a little dark and recessed next to the other cuts. However, my audiophile nitpicking is just that, nitpicking. This powerful song wears its faded jeans with pride, and it ought to be performed.

Cut four is "Tried so Hard." It will be for many the best song on the album. It's what forced me to buy the album back in the early 80s. It was penned by The Byrds' most prolific songwriter, Gene Clark (1944-1991). Gene's story is a complicated one. He was a tortured soul by most accounts, but he wrote some great songs. This one comes from 1966 during his post-Byrds period when he recorded an album with the Gosdin Brothers. Readers should hear both versions, so they can hear the striking difference between the original and the Burrito reimagining. Vocally, this is a group effort with an occasional lead by Hillman. It opens with powerful acoustic guitars on the left and the right, and an electric guitar in the middle. On this cut the electric bass sounds just as powerful as the guitars. It's easy to hear how the Eagles were inspired by the combined voices in this song.

Cut five is the Roberts-Hillman composition "Just Can't Be." It opens with an incredible blues groove coming from a very well-recorded electric guitar. The pace of this song is easy going, and you can practically feel the heat coming from the tubes inside the amp. And there are a lot more guitars to be found, including some incredible sounding slide guitars. I say "guitars," because whoever was playing the slide guitar overdubbed an additional slide guitar part, providing the sound of two slide guitars. The singing is by Hillman and he's double-tracked, so he sounds like a duo. The lyrics aren't memorable. This song is simply a vehicle for the guitars and the always-welcome sound of Hillman's voice. Funky country blues is the best way to describe this song.

Cut six is a Bob Dylan song called "To Ramona." It does nothing for me, and neither does Bob's original, so I never play it.

Cut seven is the Rick Roberts song "Four Days Of Rain." I love it. Contrary to the dreary title, it's a happy song about being in love and sunshine. It's Southern California's answer to Paul McCartney's "Good Day Sunshine." Adding to the happy-go-lucky lyrics is a band playing at top of their game. My notes say "this sounds like Firefall." Well, yes, of course it does, because Roberts is the singer. He opens the song by playing a beautifully picked acoustic guitar. He's quickly met by the sparse sound of Michael Clark's gentle bell shot, balanced by a thud from his kick drum. Clark does this twice, the second time a little softer. A treat for us audiophiles is the perfect timbre of the pillow-stuffed kick drum. The song becomes colorful at eleven second mark where we're greeted by the song's main theme, played by Sneaky Pete on his steel guitar. Soon we have Clark pounding the song's beat on his snare drum, Robert's wonderful vocal, and the rest of the stellar band. Feeling great is this song's purpose, and I feel great whenever I hear it.

Cut eight, "Can't You Hear Me Calling," is a hot number about running down to the local bar, getting drunk, and having fun. There's a little bit of girl trouble mixed into it, but, hey, country rock contains country music! Bernie Leadon's lead electric guitar playing is smokin' hot. Heck, the whole band is smokin' hot. And if that isn't enough, the sound is smokin' awesome. This is the album's best demo cut. Musically, this is as close to cruising down the road in a shiny new sports car as country rock can convey. My gut tells me this was performed when the band returned from intermissions. My scribbled notes say "Pour me another drink and let me get loose and crazy." Just don't forget to turn the volume up, but not before you grab me a cold Guinness! The lead vocal is once again Hillman and he sounds superb. He's also laying down the funkiest bass lines I've ever heard from him. And, I should add, Clark's drumming is in-the-pocket perfect.

The album closes with a bluegrass song, a Roberts' original called "Why Are You Crying." Considering the bluegrass backgrounds of both Hillman and Leadon, and Roberts' upbringing with sixties era folk music, I'll bet a bluegrass set was part of the band's concert repertoire. I've caught myself singing this song many times throughout the last four decades. It's catchy. The only instruments are Leadon's banjo and Roberts' acoustic guitar. This ought to be a bluegrass standard, as it rivals the best I've heard. Roberts' vocal on this bittersweet love song is sincere and riveting, and the sound quality is super clean. My only gripe is borderline trivial. I think it would have been nice if the recording engineer had chosen to record this scaled-down cut with just two mics, thus capturing some additional room ambience.

As much as I love The Byrds, I can't ever remember listening to them and thinking "Man, that Clark is an incredible drummer," but on this album he rises to that level. In fact the entire band is equally tight. It's amazing that this album is still a secret. I'm sure it's streamable, but I have no idea if or how it was mastered for the format. If it's cloned from the Mobile Fidelity CD, that would be better than a modern de-noise job. Speaking of CDs, I checked to see if one is currently available. Yes, one can be found. It's an Australian import on Raven, but I'm always leery of weird imports. Many of them just don't sound right.

There's something about Chris Hillman's voice that comforts me. I'm sure it has a lot to do with the fact that two of my favorite songs by The Byrds are "Have You Seen Her Face" and "Time Between," both Hillman originals, which he also sang the lead vocal on. The words that kept going through my mind during my recent visit with this album are: "This is the best Chris Hillman album I've ever heard." And it is! Hillman's contributions to rock and bluegrass are enormous, but with all due respect to Bernie Leadon and Rick Roberts, I hear a Chris Hillman and friends project. Perhaps it's because I've seen Chris three times in concert. I can't think of a rock legend who seems more like an old friend than Mr. Hillman. I'm glad to have had the opportunity to shake his hand at the now defunct Coffee Gallery in Altadena, California. (I shook hands with Gene Clark after a Ringo Starr concert at the Greek Theater, but the experience was not as positive.)

Hearing Rick Roberts is like visiting with that favorite friend of your best friend. He's a great singer, songwriter, and guitarist. I can't help but wonder why he and Chris didn't write more songs together, or why they haven't performed together in decades. Then again, Rick spent a lot of his time creating music with his Firefall mate, Larry Burnett. The record collector in me has never, and will never, pass up a clean garage sale copy of Firefall's self-titled first album (Atlantic SD 18174). Perfect it's not, but four of the album's cuts are excellent. Larry Burnet's "Cinderella" is a folk-pop classic, and the Roberts penned "Livin' Ain't Livin'" is a power-pop masterpiece that's always a delight.

There isn't much more I can say about this album. It speaks to me. The band's previous albums do not, and the Mobile Fidelity CD sounds great on my Audio Research-driven Legacy speakers!