Magnificently performed by the string quartet Matangi, this is music written in the second half of the twentieth century by Russian and Ukrainian composers that is ideally suited to the bizarre world in which we find ourselves today in March of 2022. It is intense music of challenge, protest, and criticism. It was intended to provoke and unsettle. And it is some of the most intensely beautiful music for string quartet ever written.

Outcast, Matangi. Northstar Recording 2022 (DXD) HERE

Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998) – String Quartet No. 3 (1983)

Valentin Silvestrov (b.1937) – String Quartet No. 1 (1974)

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) – String Quartet No. 8 (1960)

This album is an ode to musical troublemakers and outsiders: three Soviet-Russian-Ukrainian composers who wrote music that went dangerously against the tastes of the regime under which they lived. Described as "avant-garde" or "western," these composers stuck their necks out with their work, risking their careers or even their personal freedom. Shostakovich, for instance, always had a packed suitcase in readiness for his possible arrest by the KGB under Stalin.

The album opens with Schnittke's third string quartet which boldly quotes from Orlando di Lasso's Stabat Mater, Beethoven's Great Fugue Op. 133, and Shostakovich's DSCH theme from his String Quartet No. 8. This quartet demonstrates Schnittke's propensity to intertwine highly disjunct, abruptly contrasting styles and musical periods to create a new whole. It can be jarring. It is always thought provoking. His use of dramatic chromaticism throughout the work keeps one constantly off-balance, just as in the music of Shostakovich whose works Schnittke greatly admired.

The emotional world of this third string quartet is constantly falling apart, by turns confused, manic, hysterical, depressed, bitter, and utterly despairing. Yet it holds. It holds the unresolved tensions of these disparate sources through its embrace of them. As one music critic wrote, "Schnittke's Third Quartet astounds though the unresolved tension of these opposites, the passage of great art into wreckage, back into great art."

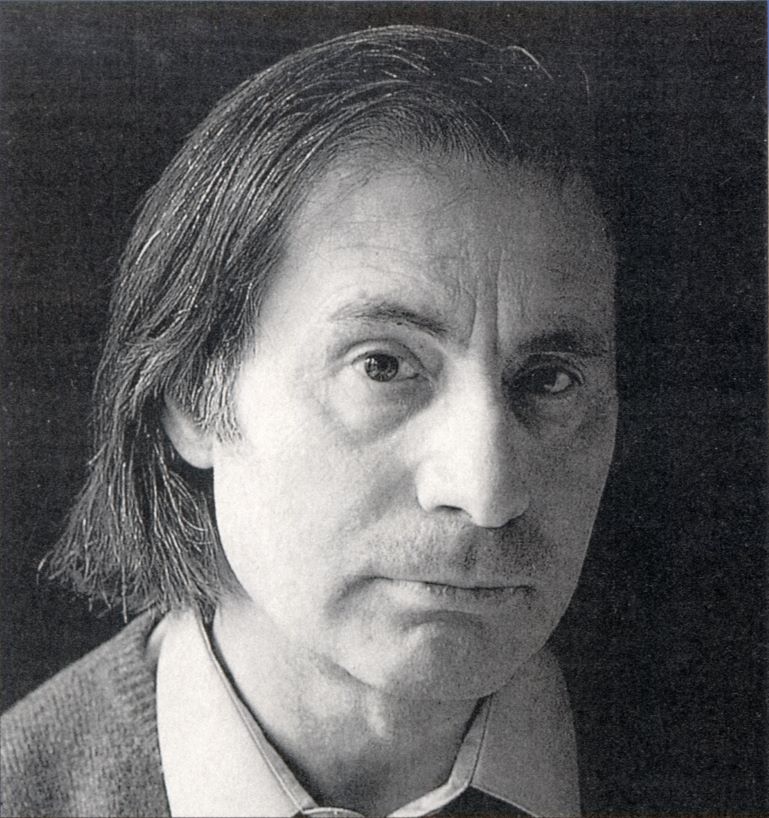

Alfred Schnittke, 1994 - photo by Ewa Rudling, public domain

Schnittke and his music were often viewed suspiciously by the Soviet bureaucracy. His First Symphony was effectively banned by the Composers' Union. After he abstained from a Composers' Union vote in 1980, he was banned from travelling outside the USSR. Schnittke's music became more widely known abroad in the 1980s, thanks in part to the work of émigré Soviet artists such as the violinists Gidon Kremer and Mark Lubotsky, the cellist and conductor Mstislav Rostropovich, but also by the conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky. Due to restrictions on performances of his compositions, Schnittke turned to writing film scores in easily digestible Socialist Realist style to make a living, just as did Shostakovich. In 1985 Schnittke suffered the first of two severe strokes after which he continued to compose. In 1990, Schnittke left the Soviet Union and settled in Hamburg, Germany where he died on August 3, 1998, following yet another stroke in 1994. This last stroke left him almost completely paralyzed and largely unable to compose except for some short works which he managed to complete.

Valentin Silvestrov, 2009 - photo by Smerus, cc

Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov's String Quartet No. 1 of 1974 takes us into an entirely new direction—very quiet, very contemplative. But Soviet authorities considered this work to be avant-garde, and therefore inadmissible for the entertainment of the people. Silvestrov was refused membership in the Union of Soviet Composers, which directly resulted in his works being withheld from public performance. The consequences were far-reaching, and in the Soviet Union era Silvestrov was not visible to the listening public. But appreciation for his compositions grew in the West. The Koussevitzky Foundation awarded a prize for his 3rd symphony. The Dutch Gaudeamus foundation also awarded him a prize for his work Hymnen.

Though a leading figure in the former Soviet Union’s avant-garde in the 1960s, Silvestrov subsequently shifted his compositional landscape. As noted in the enclosed booklet, Silvestrov once said of his early days as a contrarian avant-gardist: "Composing radical music was like working with a mountain of salt that you used up completely. Now I take a handful of salt, just for the taste."

But here in his String Quartet No. 1, we are still full-on avant-garde. Albeit softly, quietly, introspectively so, for a thoroughly engaging 25 minutes of uninterrupted performance. The music starts with a lovely theme and then takes a winding journey through various musical landscapes, harmonious and dissonant, before arriving back to its beginning in nicely crafted resolution.

Perhaps this work is a prelude to his later, more well-known period of neoclassical post-modernist compositions. In this String Quartet, it sounds almost as though he is saying "Come with me. We will be walking into a new land soon, but not just yet." But, of course, this is just me fantasizing a bit as I listen to this piece because I know what came before and what will be coming after. This is Silvestrov demonstrating his observation that “the most important lesson of the avant-garde was to be free of all preconceived ideas, particularly those of the avant-garde."

Silvestrov's music is accessible and demanding at the same time. It cycles between modern chromaticism and melancholic tonality creating a continuing sense of ambiguity and disquiet. And it is guaranteed to stay in your head.

Dimitri Shostakovich, 1950 - credit Deutsche Fotothek, cc

Much has been written about Shostakovich's life and his constant struggles with the Soviet regime. I will not reprise that here. Instead, let's focus on this very famous and often performed String Quartet No. 8, an amazing deeply personal work. The piece was written shortly after he reluctantly joined the Communist Party in 1960, telling his daughter he felt that he'd been blackmailed. Shostakovich's friend, Lev Lebedinsky, said that Shostakovich thought of the work as his epitaph and that he planned to commit suicide around this time.

The Borodin Quartet's premier recording of this work in 1962 (Decca SXL 6036) towers over all the competition even today. Music critic Erik Smith wrote in the liner notes of that release, "The Borodin Quartet played this work to the composer at his Moscow home, hoping for his criticisms. But Shostakovich, overwhelmed by this beautiful realisation of his most personal feelings, buried his head in his hands and wept. When they had finished playing, the four musicians quietly packed up their instruments and stole out of the room."

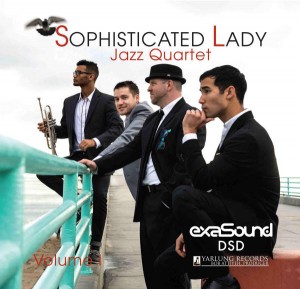

Original Decca SXL 6036 cover for performance by the Borodin Quartet from 1962 - courtesy Discogs

This performance by Matangi is powerful, insightful, and beautifully played. They capture the depth of emotion and anguish that Shostakovich poured into this work. Their performance of the second movement, Allegro Molto, is stunning—with immense power, dynamic contrasts, and drive. It fully equals that of the Borodin. And this is very high praise, indeed, as the Borodin's performance has been my benchmark for decades. They roll seamlessly into the Allegretto (third movement) playing the chromatic contrasts for all they're worth; and the opening of the fourth movement Largo simply reverberates with power, but then slowly, lyrically, and with a great sense of longing flows to a sublime conclusion.

In sum, one of my favorite string quartets is here performed superbly, with total command, total control, immense power, and in deep sympathy with the emotional depths which Shostakovich delves.

Throughout this album, Matangi have brilliantly exceeded all of my expectations. Their ensemble playing is superb, the unison in their massed strings attacks are precise and powerful, their navigation of dynamics and tonal contrasts unerringly on target, their ability to convincingly pull one into the emotional depths and drama of the music simply captivating. Theirs is the kind of music making one hears only from an ensembles who have been performing together for many years—in Matangi's case, for over twenty years. They seem to read each other's thoughts, their communication during performance appears innate and totally seamless.

Have I enjoyed their performances across these challenging works? Oh, indeed I have. And I can't wait to explore more of their music making. They are superb.

And I have to acknowledge that, as great as is my admiration for these performances, Bert van der Wolf's astonishingly clear, detailed and acoustically natural sounding engineering adds to my enjoyment of this album tremendously. All of the Bert's recordings are sonically exceptional. This album continues with that high standard to which Bert holds himself accountable. The recorded sound is so good, I simply forget about the sound quality and totally immerse myself into the musical performance Bert has brought into my home. Bravo!

My highest recommendation, all around.

Members of Matangi, seated, listening to a take during the recording session. Courtesy Northstar Recording.