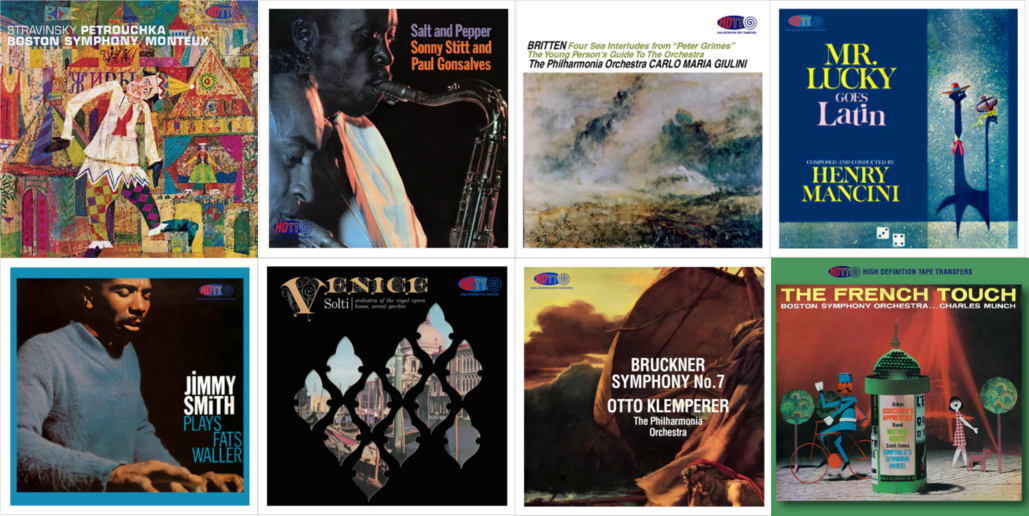

Saint-Saëns, Symphony No. 3 "Organ Symphony," Paul Paray, Detroit Symphony Orchestra, with Marcel Dupre organ. 1957, 2023 (DXD DSD256) HERE

Paul Paray's 1957 performance of the Saint-Saëns Organ Symphony is another of the great recordings in the Mercury Living Presence catalog. Its release by HDTT in gorgeous high resolution sonics is cause for celebration!

The Mercury Living Presence recordings which I so loved throughout my days listening to vinyl have a very distinctive sound. It is very much a third row presentation, very upfront and impactful. But, these great Mercury recordings also present a huge soundstage, with excellent inner detail, superb micro-dynamics, and a marvelous sense of three-dimensional air around instruments. That three-dimensional air around the instruments is what creates, for me, the sense of real instruments performing in a real acoustic space—and it's all part of the Mercury Living Presence magic.

And this release by HDTT brings back that Mercury Living Presence magic.

As is so often the case with the HDTT releases, this release sounds better to my ears than the CD in the recent 2022 box set from Universal. Pitch is now corrected (for perhaps the first time ever) providing fuller, richer string tone and better match to the organ. The volume of the organ has not been diddled. It is left as found on the tape and not boosted as on the Universal CD. In the second movement (Poco Adagio) we can once again hear the organ providing its dark, mysterious support to the lower strings, not playing the dominant protagonist (again, matching my recollection of the LP). But most importantly, we once more get to hear the three-dimensional air around the instruments, the sense of real instruments performing in a real acoustic space. The orchestra sound once again has depth and dimensionality.

That dimensionality of which I speak, that sense of real instruments performing in a real acoustic space, is soooo dependent on the delicate upper frequencies that capture the harmonics. It's those upper frequency harmonics that give a sense of real life to the recording, and without which the timbre of the instruments is not as immediately apparent. Unfortunately, it is precisely this aspect of the recorded sound which is so easily damaged in mixing and mastering. The loss of this information is what so often disappoints me listening to various reissues. But, here in this new reissue from HDTT, that dimensionality, that sense of real instruments performing in a real space, is back!

This new HDTT release, in either its DXD or DSD256 formats, is back to what the Living Presence magic was all about.

If this HDTT release is now ON PITCH, how did they determine that the other reissues were sharp, including the tape from which they were making this transfer? I asked John Haley about this, and he replied:

1. It is extremely likely that a big pipe organ, at least in this country, would be tuned to A equals 440 (like a piano). They would have tuned the orchestra to match it. It is a whole lot of trouble to retune a pipe organ, and they would not have retuned it to match a higher-than-440 orchestral pitch. In contrast, it is relatively easy to retune an orchestra--they all tune to the A given to them by the oboe.

2. To raise the tuning 1 percent (where it is on the Universal CD), they would have to have tuned the orchestra to north of A equals 444. Putting aside the organ issue, that would be REALLY high. That's not impossible but awfully unlikely.

3. Subjectively, 440 just "sounds right" to our experienced ears for this recording, as compared to how it sounds from raising the pitch by 1 percent. Keep in mind that tuning high will brighten the sound of an orchestra just a little, but it will not change the timbre of the instruments in the same way that raising the pitch of a recording will. For example, the change in the sound of the strings effected by incorrectly raising the pitch is not at all what the change in the sound would be by the orchestra tuning high. Strings should remain silky even tuned a little higher, whereas raising the pitch (from where it should be) will move their sound along the path toward thin, harsh and screechy. Similarly, brass tone moves toward unpleasant, away from rounded and full.

For reference, a half step is a little more than 5.9 percent.

People want the certainty of "trusting" their equipment to give them the correct pitch without their having to think about it or deal with it. The truth is that there is no more rash assumption than that old master tapes and their copies are recorded precisely on pitch. Older tape recorders back in the 1950's could not even be relied upon to play a consistent exact pitch when playing from the beginning of a tape to the end. The reel of tape is itself fairly heavy, requiring more strength from the motor to move a full reel than an almost empty one. This is even more true for half inch tape. And we are talking about fairly small speed errors here. Also, a tape machine that has seen a lot of use may not play exactly as it did when new.

Unless double session tapes were recorded at the recording sessions--one to cut up for editing (by splicing) and one to keep, many edited (mixdown) masters start as copies of the session masters. This means two different tape machines are involved already. Plus a production master having no splices in it is by definition yet another copy. And we generally don't know what the practices were that generated a "master tape" when we pick one up to dub it 50 years later. Bottom line--it is never that simple, and you really have to check pitch every time, especially with old tapes. For home recordings and live recordings, multiply the likelihood of pitch inaccuracy.

This is obviously a big topic, with lots of variables, but the solution is always the same--check the pitch. Yes, sometimes we need to know something about tuning. I have collected materials about that over the years. Variations from 440 tend to be geographic. For example, London is pretty reliably a 440 town. However, orchestral tuning in Vienna is generally 442 or 443. Pianos in Vienna are generally tuned to 442. This introduces some uncertainty, but we do the best we can. Very often, where pitch errors exist, they exceed these small differences.

Some additional notes for those likely to ask:

- No, HDDT did not use the Plangent Processes in transferring the tapes

- No, HDTT did not have the original master tapes to work from

- No, HDTT does not tell us what source tapes they used

- Yes, to me this does sound better than the recent Universal CD box set release

So, there you have it. To my ears, the result of Bob Witrak's and John Haley's efforts is a decided improvement, particularly in the strings which now have a full, sweet sound, in the balance of the organ, which is now back to what I recall hearing in the original vinyl, and in the depth and dimensionality of instruments and orchestra.

So, what about the performance?

Oh, sorry. I presumed most would know this recording and performance, but was reminded that not everyone has been around since the dinosaurs like me. Allow me, then, to expand a bit about this performance.

First, why do you want this performance if you already have the superb RCA Living Stereo recording by Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra that I enthused over just a few months ago HERE? The simple answer is: You may not. The Munch is a great performance and a great recording. It is the recording on which I first imprinted and one I hold in high regard. If you are only looking for one performance of a given piece of music, you could stop there.

Throughout the half-century since its initial LP release, Munch’s 1959 RCA recording of the Organ Symphony with the Boston Symphony has been universally hailed as the reference against which all others are to be measured (and invariably fall short).

But I'm of the school that believes serious music is far more nuanced than any single performance can ever reveal.

If, like me, you enjoy hearing different ways of performing a work, or you'd prefer something a bit less romantically infused, or you'd prefer a more upfront, third row seat to the orchestra, then this Paray recording may be just what you need. Paul Paray's approach to the music is cooler, more precise, with more stress on clarity of articulation than sentiment. But still with fire, power, and massive color. Some may find his approach a bit too fierce. I find it the perfect contrast, perfect antidote, to the Munch.

As Peter Gutmann notes in his excellent article surveying various of the recordings of Saint-Saëns' Organ Symphony, "Paray bestows a magnificent idiomatic reading of elegance, grace and precision, complete with an authentic 'French' sound from the orchestra he had trained in Detroit... With prominent inner voices, Paray's lithe, supple, evenly-paced approach with restrained dynamics revels in the score’s abundant coloration..." HERE

And, as he goes on to note, the precise stereo imaging of the Mercury recording (all achieved elegantly by Bob Fine with only three microphones) "captures the clarity of the textures and invites understanding and appreciation of Saint-Saëns' gifts of orchestration that the blurrier acoustic of Munch and many others tends to obscure."

For a note about the Paray performance on the original Mercury Living Presence LP, I recommend to you the article by Positive Feedback's Greg Weaver who says, "I can’t lie, I LOVE this record." HERE

Overall, this is a very remarkable release and I highly recommend it to you!

You might also be interested in further exploring some other recordings by Bob Fine, the legendary recording engineer behind the Mercury Living Presence recordings, or the recordings by Paul Paray. HERE and HERE.

For the adventurous who might like to explore other performances of the Saint-Saëns Symphony No. 3, HDTT offers five additional recordings by different conductors and orchestras: Maurice Abravanel, Ernst Ansermet, Zubin Mehta, Charles Munch, Georges Pretre, Hans Swarowski. Wonderful to compare, each is very different. Available via this search link.