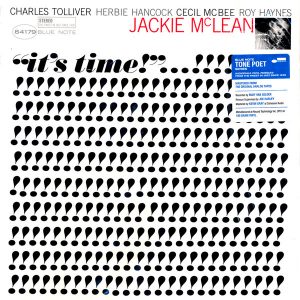

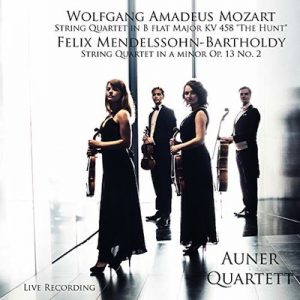

One can only hope that this release marks the beginning of a full cycle of recordings of the Beethoven Sonatas for Violin and Piano from Rachel Podger and Christopher Glynn. If this initial album is any indication of what might be in store, such a cycle would be a wonderful gift.

Beethoven Sonatas for Violin and Piano Op. 12 No. 1, Op. 24 "Spring", and Op. 96, Rachel Podger, violin, Christopher Glynn, fortepiano. Channel Classics 2022 (DSD256) HERE

Here we have two gifted musicians thoroughly attuned to playing music of the baroque, classical and early romantic periods now moving into the world of music Beethoven created. Beginning with Beethoven's first Violin Sonata, Op. 12 No. 1, written in 1798, then following with the fifth "Spring" sonata of 1801, and concluding with the calm ethereal beauty of his tenth and final violin sonata written in 1812, Podger and Glynn take us on a grand tour of exquisite performances.

Their performances don't sound anything like the performances we are attuned to hearing using modern instruments. Christopher Glynn plays on a straight-strung Erard piano from 1840—it has a completely different sound quality from a modern grand piano. Its tone is softer, more rounded, with a lovely woody resonance in the bass. Rachel Podger is playing the "Maurin" Stradivari violin of 1718 on loan from the Royal Academy of Music, an instrument with a silky beauty of tone but of excellent power. It is a "modern" instrument and was played by the first violinist of the Lindsay Quartet, Peter Cropper, so it's clearly not a "period instrument." Nonetheless, in Podger's hands the tonal qualities of the violin balance exquisitely with the sound of the Erard to deliver a rich blending of harmonic complexities to these performances.

This is simply a very different listening experience so very different than most performances with a Steinway "D" Model grand piano, as wonderful as those instruments are—far more evocative of the time period in which these works were composed.

Listening to these three sonatas is like being invited into the parlor for a pleasant conversation among erudite, cosmopolitan fellow travelers who can talk intelligently about the world. That conversation moves intelligently between violin and piano, neither taking primary stage, neither seeking a spotlight, but both having interesting points of view to share. In all three works, it is an engaging give and take that is occasionally in opposition, frequently in support. It is a musical collaboration which one feels privileged to overhear.

Violin and piano were the instruments Beethoven himself played and knew best. In a series of ten sonatas, Beethoven explores these instruments with an astonishing originality and invention that has never been surpassed. This originality did not win approval of audiences and critics in its day. As Clemens Romijn writes in the liner notes, "It was too brutal, too idiosyncratic, too restless, too obtrusive. The Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung in Leipzig was quite merciless: 'It cannot be denied that this man goes his own way. But what a bizarre and laborious way it is! Learned, learned, forever learned, no naturalness, no singing quality! Not a single melody, everything sounds recalcitrant, so Beethoven and the violin that one loses all patience and pleasure.' Beethoven riposted dryly: 'They understand nothing.' "

This same originality is still shocking to us today.

Says Rachel Podger, "It shocks because Beethoven’s musical language is embedded in the Classical style of his time (however Romantic it might sound), and his spirit of adventure and daring to push the boundaries of this style makes his music sound and feel fresh and revolutionary, even two centuries later."

Podger and Glynn add to the freshness with which we are able to hear these works by their carefully crafted re-thinking of how to present them. Podger is here moving forward in time from her roots in the Baroque and Classical and Glynn is moving backward from his more Romantic period roots. Where they meet is this delightful crossing ground from the models of Mozart, Haydn and Salteri and the later models of Schubert, Schumann and Brahms. It is this fertile early stage of the later Romantics that Beethoven so brilliantly innovated a revolution in music.

And the album follows this path of innovation. The first sonata, Op. 12, No. 1, published in 1798, audibly follows the models of Mozart and Haydn, with whom Beethoven had recently studied, even as his own individual voice strains at these 18th-century confines. So often it is played with a full-throated explosion of demonstrative sound. Instead, Podger adopts a more intimate, conversational unfolding of the music. Her sound is more contained, yet the interaction between the two players is palpably 'live’ and volatile.

The famous fifth "Spring" sonata (Op. 24) sounds full of contentment and lyricism. It received the nickname "Spring" not from Beethoven but from a contemporary who imagined he heard the spring in the lyrical opening melody. In fact, this lyricism runs through the whole piece. Podger and Glynn play the piece with a cheerful, joyful, good humor that engages throughout. There is no over-sentimentalizing here, they move the music forward briskly. Even the famous second movement, marked "Adagio molto espressivo" has a forward propulsion to lyrical expressiveness with which they imbue it. And the partnership of violin and pianoforte is perfectly aligned.

The final tenth sonata, Op. 96, was written at the beginning of Beethoven's visionary "late" period and it shares the lyrical expansiveness of works of that period such as the Archduke Trio, Op. 97. The closing movement of the tenth sonata is a departure from most final movements of the period. Instead of bravura and volume typical of the final movements of most Viennese compositions of the day, the Beethoven's tenth ends with a series of seven variations on a pleasantly humored theme. This is said to have been a concession to the French violinist, Pierre Rode, who did not care for such bravura sounds and who would be first to play the violin part of the work in a private performance with Archbishop Rudolph, youngest son of Emperor Leopold II and brother of Emperor Franz, at the piano.

Glynn and Podger have been delivering concerts of the Beethoven violin sonatas since 2020, with this their first recording. Perhaps their traversal of the sonatas in concert has laid the foundation for recording and releasing the remaining seven sonatas. One can but live in hope.

I cannot conclude this article without applauding the tremendous contribution recording engineer Jared Sacks makes yet again to my enjoyment of this album. Recorded in May, 2021, at St. Johns Church, Upper Norwood, London, Jared has once again found a seductively beautiful location to allow the sound of the instruments to fully blossom in a natural acoustic setting. His microphone placement then captures this as a live performance in which the musicians are brought into our listening space. Detailed, nicely resonant, with excellent capture of the texture and harmonic overtones of these lovely instruments, this recording is a "top-of-the-pile" recording for those seeking truly natural sounding "live" performances as their ideal for recorded music. Excellent once again!

Images courtesy of Channel Classics.