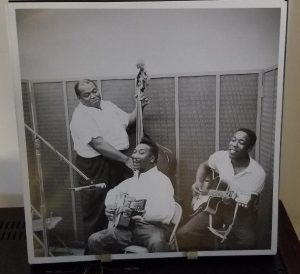

Commencing with the scintillating opening to Ernst von Dohnányi's Sonata for cello and piano, op. 8, and finishing with the abrupt falling phrase that concludes Shostakovich's Sonata for cello and piano, op. 40, Fernando Arias, cello, and Noelia Rodiles, piano, take us for a joyous ride through some superb music. Over the past several days I've luxuriated in this delightful new recording Slavic Soul—another outstanding recording from Eudora. Highly recommended!

Slavic Soul, Fernando Arias, cello, Noelia Rodiles, piano (2021 (DSD256, Pure DSD) HERE

Listening to pianist Noelia Rodiles is always a great pleasure, she has such a delicate, nuanced touch in her playing. I've written before about her earlier solo recording for Eudora, The Butterfly Effect, and I think you will enjoy exploring her performance here. I look forward to hearing more from her. So often one focuses on the cellist in works such of these, but, for me, Rodiles is the huge draw. Her pianism is a full equal partner (and perhaps creative lead) to that of her collaborator on the cello, Fernando Arias. Together these performers forge a partnership that is fully complimentary and synergistic, one not deferring to the other, both providing equal measure of musical insight, drama, and emotion.

Slavic Soul is a collection of works for cello and piano by Dohnányi, Janáček, and Shostakovich, each of whom has a unique flavor and outlook to savor.

Ernst von Dohnányi's Sonata for cello and piano, op. 8, is work that needs to be performed more often. I'm so glad to see it included in this album. Composed in 1899 when Dohnányi was 21, the work is, as Donald Tovey writes in Cobbett's Cyclopedic Survey of Chamber Music, "an important work. The first movement is weighty and majestic and the themes are well able to support the Brahmsian treatment. A lively Scherzo with a quiet trio shows that the intention of the work is not tragic and this is born out in the theme and variations of the finale."

Dohnányi lived from 1877 until 1960 and was one of the most important and influential Hungarian composers and pianists of the 20th century. Dohnányi and his friend Béla Bartók, three years his junior, always admired each other but could not have differed more in terms of style and character. This is apparent in their diametrically opposed approaches in their use of Hungarian folksongs, Bartók pursuing the cultural and social aspects of his collections of folk songs, Dohnányi presenting gypsy melodies in the Romantic fashion of Liszt and Brahms. Dohnányi's foundation in German Romanticism, notably the works of Brahms, is readily evident in the work here. But this work, while heavily indebted to Brahms, can firmly stand on its own with its bold harmonic language, sweeping melodies, and instrumental brilliance of both cello and piano. This is a fine work nicely suited for collaborators such as Rodiles and Arias who truly partner in their performances.

Leoš Janáček (1854-1928), as described in the enclosed booklet for the album, "is regarded as a late-blooming genius, a composer who did not find his own true voice until the later years of his life. Then, however, he enjoyed a genuine explosion of creativity that led him to assimilate the music of figures such as Debussy or Berg without losing his own identity, and to become one of the most respected composers of the first half of the twentieth century." His Pohádka (Fairy Tale) (1910), performed here, is a work of Janáček's maturity. "It is a powerfully dreamlike evocation of the ever mysterious atmosphere of childhood in three concise movements through which the cello and piano progress amid rhythms and colours tinged with an indefinable flavour." (booklet)

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) composed our final work, the Sonata for cello and piano, op. 40, in 1934, during a heady period in which Shostakovich experienced great success and approbation. It's first performance came just before the censure by Soviet authorities of his music, notably the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which was deemed too bourgeois and decadent for the Soviet people. The sonata is everything that Stalin and the Soviet press said his opera was not: disciplined, classically proportioned, sonorous, and eminently lyrical.

There is more than a hint of satire in the biting, quasi moto perpetuo second movement, but the dynamism more than compensates. The following Largo movement is somewhat a precursor of his later style, "though it is far less angular and more compassionate than desolate, with an almost Schubertian degree of lyrical grace." (Gustavo Dudamel, LA Phil program notes)

The finale is again athletic and makes a ready impression, with technique and sass amply displayed in both parts. Rodiles takes the piano's pell-mell cadenza at the end of this movement in wonderful form with extreme energy. Simply a delightful conclusion.

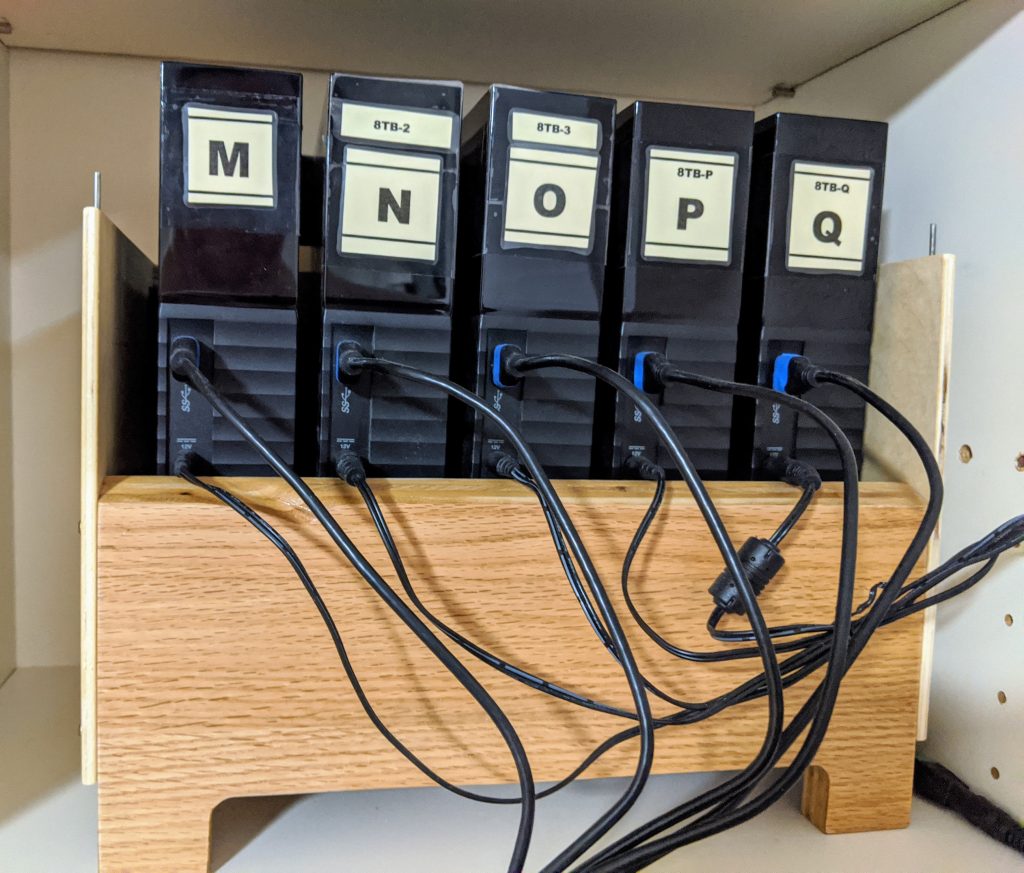

Gonzalo Noqué, founder and chief recording engineer for Eudora, has again done a superlative job with this recording. As usual, the recording is direct to DSD256 with no interim DXD processing, so it is Pure DSD. And it sounds like it: pure, clear, transparent, tonally natural. The miking cleanly separates the artists in space, but captures a holistic space full of natural acoustic ambiance. Congratulations on yet another marvelous recording!

Do I recommend this recording? You betcha.