Sometimes, the most improbable juxtaposition of musical styles, sounds, and textures just works and, when spotlit in breathtaking clarity, as with Mobile Fidelity's Platinum Ultra Disc One-Step version of Miles Davis's Bitches Brew, it's brilliant.

When I was a child, my mother cooked and served our meals at home. Occasionally, some spillover occurred between the protein, fruit, vegetable, and grain (or starch) portions, and when that happened, my youngest brother, Pablo, protested vehemently—to which my mother would respond, "It all goes to the same place!"

I wasn't as fussy, nor was my brother, Luis Ayllon, who later trained in classic French cuisine at École de Cuisine La Varenne in Paris and became a noted chef in Chicago's suburbs at places like Suzette's Creperie and Cabs Wine Bar Bistro (where he was chef and owner for 18-plus years) with his fusion of various traditions with science and experimentation in his contemporary American cuisine approach.

Many music purists share a rigid view with music genres similar to Pablo's. However, acclaimed producer Quincy Jones took umbrage with this attitude when it came to the creation of Miles Davis' landmark album, Bitches Brew.

"People were telling us not to mix jazz with rock, that myopic mentality," he said. "That's bullshit. Miles, Cannonball Adderley, Herbie Hancock, and myself used to talk about this, how you should try everything." (Faroutmusic.co.uk)

Davis had been listening to a lot of funk and rock in 1969, including James Brown, Sly & The Family Stone, and Jimi Hendrix. "He wanted Bitches Brew to possess that same raw power and rhythmic drive, pushing jazz beyond swing and bebop into something more primal and hypnotic," wrote Eric Alper. "Tracks like Miles Runs the Voodoo Down are dripping with that influence, with gritty blues guitar, pounding drums, and an energy that feels more Woodstock than Birdland." (thatericalper.com)

Selling more than one million copies since it was released, Bitches Brew was viewed by some writers in the 1970s as the album that spurred jazz's renewed popularity with mainstream audiences that decade. As Michael Segell wrote in 1978, jazz was "considered commercially dead" by the 1960s until the album's success "opened the eyes of music-industry executives to the sales potential of jazz-oriented music" (Wikipedia.com)

"The album features a unique and spontaneous jam session approach, resulting in complex compositions characterized by impressionistic soloing and dynamic rock-inspired rhythms," wrote L. Moody Sims, Jr. Defying traditional jazz structures, it created a "new sound palette that influenced a generation of musicians and led to the evolution of fusion as a dominant genre in the 1970s." For all its commercial success, the fusion movement drew some criticism over its artistic merit for its alleged departure from jazz's authentic roots. Nevertheless, Bitches Brew laid a foundation for future explorations in Fusion, which "continues to be recognized for its eclectic nature and the exciting musical landscapes it crafted during its peak." (ebsco.com)

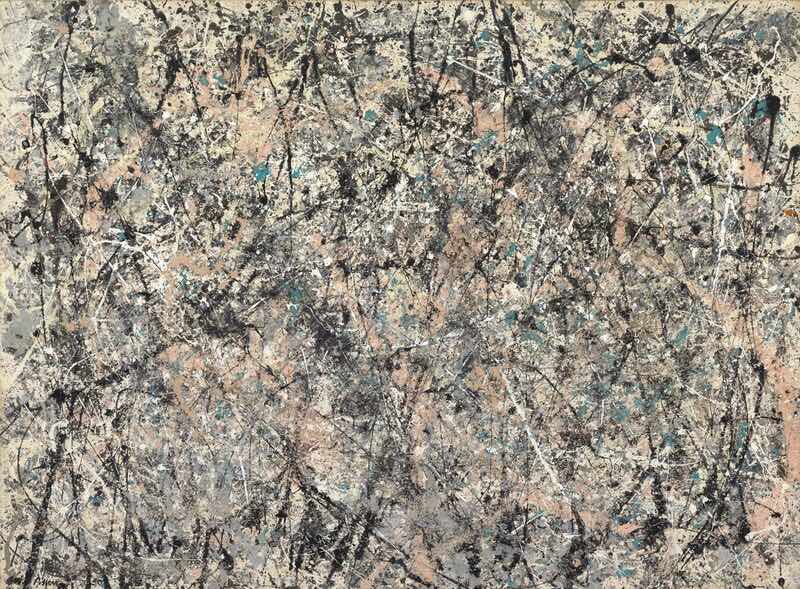

"Number One" oil painting by Jackson Pollock, a a leading artist in the abstract expressionist movement, 1951 (photo courtesy of /www.nga.gov)

The Listening

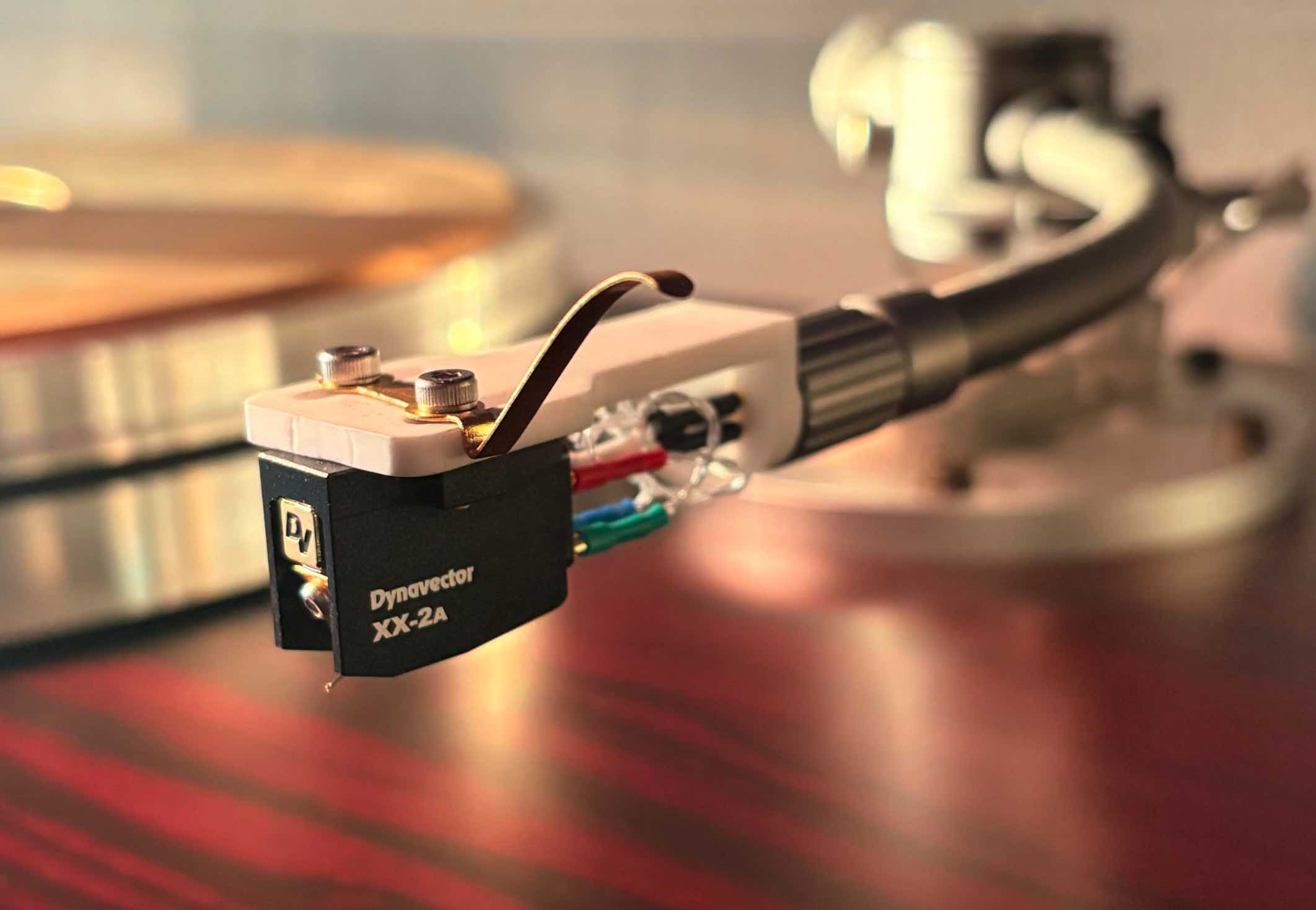

A light, audible blip signals that the stylus of the Dynavector XX-2A phono cartridge drops on side one of the record, and for a few moments, there's dead silence as the diamond tip glides along the vinyl's pristine grooves.

Why so silent? It's the 55th Anniversary Edition audiophile format release of Miles Davis' RIAA-certified, Platinum edition of Bitches Brew is an UltraDisc One-Step 180g 33RPM 2LP Set. Sourced from the original master tapes (1/4" / 15 IPS analog master to DSD 64 to analog console to lathe), strictly limited to 5000 numbered copies, and pressed at Fidelity Record Pressing in California, this definitive-sounding anniversary reissue enhances every element of a double album that established new possibilities for studio recording techniques.

Silence gives way to brushed quarter notes on a snare and Hi Hat, and meandering, warbling keys and a plucked double bass—seemingly warming up—join in. Bernie Maupin's bass clarinet lows. McLaughlin's electric guitar teases a spare comp note or two, as does Davis with a little throaty trumpet squeak. One drummer's ride cymbal keeps time while another's rides the Hi Hat (Lenny White and Jack DeJohnette share drum duties). There's a nervous, pensive energy that gives way to more furious activity as nocturnal mice overcoming predatory fears to run rampant in a field, or a simmering soup approaching the boiling point.

The rhythm section is comprised of two bassists (one playing bass guitar, the other double bass), two to three drummers, two to three playing electric piano, and a percussionist, all playing simultaneously. (Tanner, Paul O.W.; Maurice Gerow; David W. Megill. "Crossover—Fusion". Jazz, 6th Ed.). This combination lays down unique musical textures and complex, dynamic interplaying as its foundation.

Miles plays a few long notes on trumpet, sounding very abstract with no clear melody, against the backdrop of a frenetic and circular, rhythm section backdrop.

Pa-pahhhhhhh! Pa-pah.

Pada-pa pahhhhh.

Pada pa da pahhhh.

Miles Davis' trumpet solo conjures a series of Pablo Picasso loaded brush strokes—bold and spare—over a Jackson Pollock canvas.

McLaughlin's guitar comps, and is replaced minutes later by the keys. Gurgling with activity, the soup is boiling over.

It's as if Jackson Pollock has re-entered the studio, shoved Picasso aside, and is dripping fresh paint on the canvas again. Then others take turn. Maupin's bass clarinet solos. McLaughlin riffs. Then it's Davis' turn. Maupin riffs again—served, alternatively, over the busy backdrop.

There's a brief denouement, with the pattering of congas, Hi Hat, and cymbals before the electric piano come alive again. Miles interjects, as if returning from a cigarette break, with a fusillade of quarter and full notes over the ethereal backdrop of keys, cymbals, bass, and congas.

I am reminded of a wine tasting back when I was drinking circa 2009, when tasted a French red varietal in a small wine shop called Wine Knows in northeastern Illinois. I fancied myself a wine snob, but when I first sampled a glass of this vineyard's red, my nose wrinkled at its borderline bitter taste. Noting this, the proprietor, Phil, cautioned me that French wines were drier than I might be accustomed. Nodding, I soldiered on and noted subtle textures and flavors relating to the roots and soil from that region of France. However, I later exited the store with a McManis Petit Syrah tucked under my arm. I realized that, French wines be damned, California red wines had just enough hints of sweetness to make them more enjoyable for my American palate.

Melody gives music that sweetness, helping it go down smoother for the listener—and its lack makes for a drier experience. Yesterday, I mentioned listening to Bitches Brew to an educator colleague of mine, and he said, "It's a rough listen."

Well, yes and no. I am reminded of a friend's fit father who trained with Hulk Hogan when he was in town, and said that he never used salad dressing, claiming that all the vegetables in a salad had distinct flavors and, if you took the time to savor them, you'd find them utterly enjoyable. Bitches Brew is like that salad sans dressing, and with the brilliant playing of musicians like John McLaughlin, Wayne Shorter, Joe Zawinul, Chick Correa, Dave Holland, Lenny White, Jack DeJohnette, and Miles Davis, it's a magnificent and seminal performance that by and large favors free-form improvisation over conventional melody.

And, lo, there are some majestic moments to be had. Bold, striking one-note phrases that are sustained and echoed enthrall, standing out against the fray like Mount Everest's summit, solid and stark against swirling dustings of snow and the jet stream's 100 mile-an-hour winds.

The use of panning and tape loops and other studio enhancements add texture and emotion. There are hints of a sonata, author Paul Tingen writes, as "Enrico Merlin's analysis notes 15 edits in the piece, including (as in "Pharaoh's Dance") several short tape loops that create a new theme (in this case at 03:01, 03:07, 03:12, 03:17, and 03:27). Another section that leaps out at the listener is the tape loop from 10:36 to 10:52, where Macero creates excitement by looping a short trumpet phrase, making it sound like a precomposed theme." (Jazztimes.com)

Throughout, you get a very organic and realistic presentation of the gorgeous tone and timbre of the trumpet, keys, and drum kit in compelling sonic landscapes. In one of my favorite passages, for example, low double meandering bass line is supplanted by a cymbals and distorted keyboards splash, and then Miles launches into an atmospheric and scintillating series of calls and refrains:

Ta da

ta da

ta da

Taaaaaa!

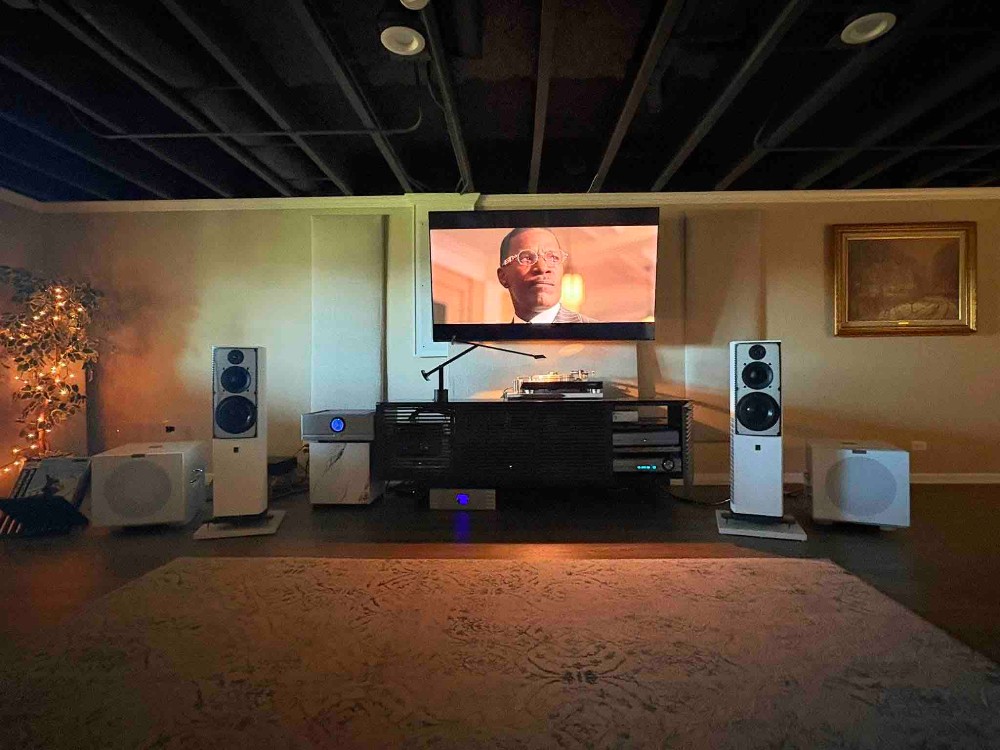

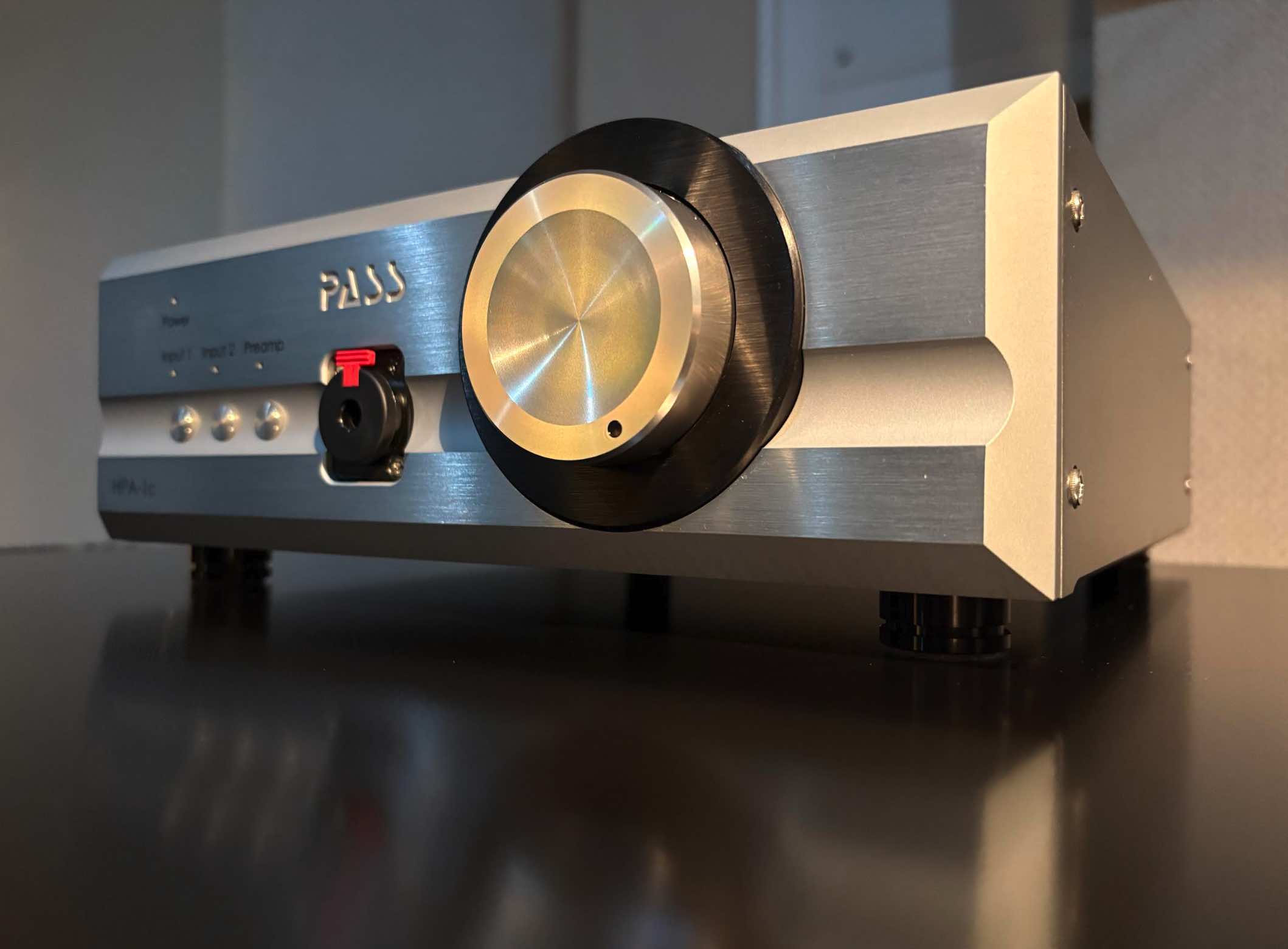

His open horn playing is a pan-seared steak at a posh steakhouse—boasting a bloody rich, softer, and rounded tone through the middle but a packing a hard-edge crust in the highs. Rife with reverb, echo, and effects, it's a golden moment in the annals of audiophelia, taking me back to the first time I heard it in a dimly-lit, packed hotel room full of rapt listeners at AXPONA (Audio Expo North America) years ago—but only better. I am hearing it in a more acoustically-optimal space, over my carefully curated equipment, and on Mobile Fidelity's UltraDisc One-Step vinyl.

A Word on One Step

"Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab's UltraDisc One-Step (UD1S) technique bypasses losses inherent to the traditional three-step plating process by removing two steps: the production of father and mother plates, which are created to yield numerous stampers from each lacquer that is cut," their press release reads. "For UD1S plating, stampers (also called "converts") are made directly from the lacquers. Since each lacquer yields only one stamper, multiple lacquers need to be cut. Mobile Fidelity's UD1S process produces a final LP with the lowest-possible noise floor. The removal of two steps of the plating process also reveals musical details and dynamics that would otherwise be lost due to the standard multi-step process. With UD1S, every aspect of vinyl production is optimized to produce the best-sounding vinyl album available today."

And Why Isn't This UD1S Pressed on MoFi SuperVinyl?

Bitches Brew is one of the few Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab UltraDisc One-Step releases—since their advent of MoFi SuperVinyl—that was pressed on 180g black vinyl rather than MoFi SuperVinyl. Why? They maintain that it simply sounds better on 180 gram black vinyl. After they closely auditioned Bitches Brew on different vinyl formats, MoFi's expert engineers determined the music on this 1970 album translates with superior definition, clarity, presence, dynamics, and balance on this version. They assert that their opening of MoFi's sister plant, Fidelity Record Pressing, with their ability to press dead-quiet 180g black vinyl, gives their engineers more options when it comes to high-quality vinyl.

All That to Say

Adam Behr, a lecturer in contemporary and popular music at Newcastle University wrote, "(Bitches Brew) launched the next generation of jazz leaders from what previous alumnus—saxophonist Jackie Mclean—had called "the university of Miles Davis," uncovering new paths for rock and studio practitioners of all stripes as it did so." (theconversation.com) And with the MoFi UltraDisc One-Step 180 gram version, you get to hear these veritable giants of jazz up close, in superlative vinyl, living and breathing with startling clarity and presence in your listening space. Now, that's sublime. But don't take my word for it; give it a spin in your own space!

Miles Davis, Bitches Brew UD1S 180 gram 33 RPM 2 LP Box Set

Retail: $125

Mobile Fidelity