The history behind the band Mercy, from Tampa, Florida, is one of the more complicated rock and roll stories that I've tried to understand. On its surface, Mercy's story is a simple tale of a one-off single that nearly topped the charts, the release of the band's only album, and the band's eventual breakup. Mercy started out as a group of high school students led by Jack Sigler, who, while in his junior year of high school, wrote a song called "Love Can Make You Happy" for his girlfriend, who later became his wife. Mercy's story could have easily ended right there, except that the song which Sigler wrote became a timeless classic.

Another part of Mercy's story is their association with the famous record producer Henry Stone (1921-2014). According to Jack Sigler, their eponymous album was recorded in Stone's eight channel studio, located upstairs from his office, in Hialeah, Florida. Stone was the man who produced "Please Please Please" for James Brown in 1958. Later on, Stone would own TK Records, the record label known for establishing the successful Miami disco sound of the seventies. In addition to owning TK Records, Stone, along with his right hand man, Steve Alaimo, produced some of TK's best-known talent, such as George McRae, Bobby Caldwell, and KC and the Sunshine Band.

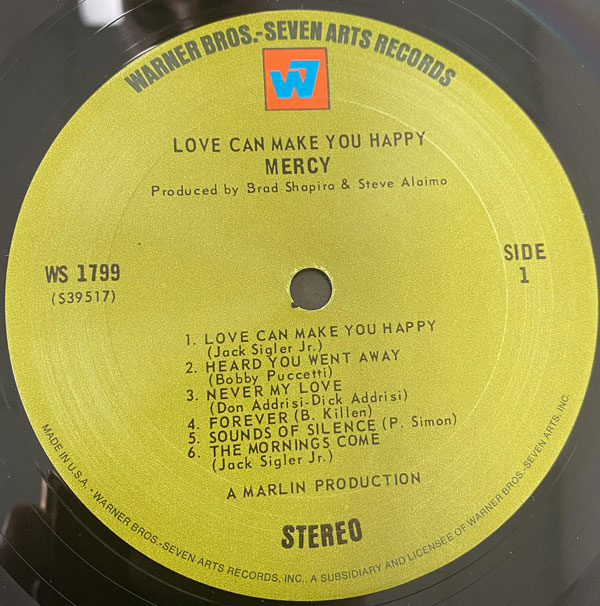

This is also the story of the hit song "Love Can Make You Happy," which Mercy recorded for the Tampa based label, Sundi, in 1968. In 1969 Mercy made a second recording of the song for Warner Brothers, which was done so Sigler could recoup his unpaid royalties from Sundi's dishonest owner, Gil Cabot. (It also makes sense that Warner would have wanted their own recording of the song, so they could promote the group's album.) In addition to their rerecording of their hit single for Warner Brothers, they recorded an entire album, one simply called Mercy (WS 1799), which is the subject of this review.

Music lovers should make themselves familiar with the song, "Love Can Make You Happy." In the realm of soft-rock love songs, it's one of the very best, rivaling, in my opinion, The Association's "Never My Love." It was released in 1969, and it became a huge hit. It even reached the number two chart position, missing the top spot only because The Beatles' "Get Back" stood in its way.

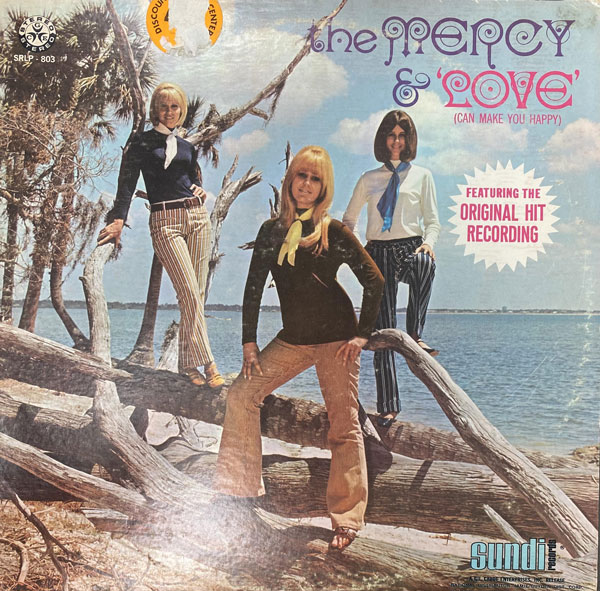

As mentioned, the Warner Brothers album Mercy is Mercy's only album. However, crooked Gil Cabot produced his own Mercy album, which preceded the Warner Brothers release. Cabot cobbled together, without Sigler's consent, an album that opens with "Love Will Make You Happy," and by adding ten forgettable easy-listening cuts, by unknown musicians, he created The Mercy & Love (Sundi SRLP-803). This album could be, sort-of, viewed as Mercy's first album, but it's only the first album to contain a song by Mercy.

Side one of the Warner Brothers album, Mercy, opens with "Love Can Make You Happy." However, much to my surprise, the Sundi recording of the song sounds much better. So, with that said, cut one of The Mercy & Love opens with an eerie electric organ, which is combined with tambourine and piano licks. A drummer keeps the time with a simple smack of the snare drum. The ethereal chorus, which consists of Sigler and his three female friends, comes in at twelve seconds. The words "wake up in the morning with the sunshine in your eyes" is perfectly reflected by the backing music. The song's chorus, "love can make you happy if you find someone who cares to give a lifetime to you and who has a love to share," comes in at fifty seven seconds, and it returns at two minutes and fourteen seconds. The song‘s total time is a well-spent three minutes and fourteen seconds. There's nothing virtuosic to the musicianship, but the combination of eerie-but-captivating music, combined with Sigler's magnificent vocal arrangement, makes the song sound luscious. It's hard to think of a song that sounds more cuddly and soothing, although The Association's "Never My Love" and The Beatles' "Here, There and Everywhere" offer stiff competition. One thing that I love about this song is the way it sticks with me after I hear it. On the surface, it sounds like fluff, but fluff doesn't penetrate your mind as deeply.

Once you've played the title cut, from the otherwise cheesy Sundi LP, you then need to place the Warner Brothers LP onto your turntable's platter. Then you need to head over to side one cut three so you can hear Mercy's own interpretation of "Never My Love." While it doesn't match the famous version's lush arrangement, or have Hal Blaine's flawless brushwork, Mercy brings a gospel-like innocence to the song that I find appealing. The three girls sing it very much like it came from a late sixties teenage Christian pop record. As I own a number of privately-pressed Christian records from the same era, I like Mercy's secular-cut-on-a-religious-album vibe. Noteworthy is Brenda McNish's piano work that emanates magnificently from the right side of the soundstage. I also love this kind of sixties era stereo. It's beautiful in its simplicity. The drums are on the left, the vocals are in the center, and the keyboards (acoustic and electronic) are on the right. A tambourine is also in the center, and the piano's ample weight makes it sound believable. Although the recording was made in Henry Stone's eight channel studio, the recording has the beguiling charm of well-mixed four channel recording.

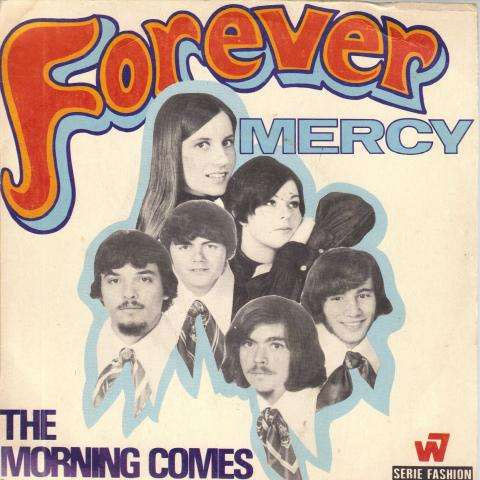

Cut four is one of the album's strongest selections. It's a cover of an obscure 1960 Chet Atkin's produced single called "Forever." It was recorded by the Little Dippers, a fictitious Nashville-based group that featured the great Floyd Cramer on piano, with The Anita Kerr Singers. The song is greatly improved by Mercy. In Jack Sigler's capable hands, the song finds its rightful interpretation. It's essentially an instrumental using scant lyrics to portray romance. As romance is Sigler's specialty, this is the standout cut of the album's first side, as the redo of the title cut was little more than a financial obligation. Stereophonically, the song is an audible example of architectural excellence. It opens with a lead guitar on the left, which is accompanied by a piano on the right. This time all eight channels of the tape recorder are utilized, so the singers are heard in panoramic stereo. The drummer's rimshots, which emanate from the left, are candy to my audiophile ears. Whether you're listening on headphones, or on speakers, the richly saturated and effortless sound invites you to raise the volume. The twangy electric guitar, which I assume is played by Sigler, is the only reminder that this song came from the land of fiddles and steel guitars. The bridge features a soprano who can really hit and hold the high notes! She starts her solo on the right side of the soundstage, then she moves to the middle, and eventually she ends up on the left. On my Sennheiser headphones she sounds like she's floating over my head. She's also a little distorted, which adds an appealing dash of psychedelia to the song. If you value great singing, great musicianship, and rich tonal balance, you're going to love this cut.

Side one cut five is an angelic sounding performance of Paul Simon's "Sounds Of Silence." The cut opens with Sigler's acoustic guitar, and singing by the three girls. They sing it like they're in church. The stereo mix is disappointing. The vocals start off in stereo, but as soon as the drummer emerges on the right, the singers are panned to the left. Again, I hear what sounds like a four track recording, but not a good example of one. The sound is also a little dull and a little smeared compared to the better sounding cuts.

Side two opens with Mercy's cover of "Aquarius," from the musical Hair. It's their attempt at sounding like a freaked-out psychedelic band. Unfortunately, freaking-out was not their forte, so it comes off sounding amateurish. A side of me likes it, because the drums sound really good. Something is happening here, but I really can't put my finger on it. Whatever it is, it's not reeling me in.

Cut four is a cover of Paul Mauriat's "Love Is Blue." As I've failed miserably at finding a good sounding copy of Mauriat's Blooming Hits (Phillips 6500-248), Mercy's performance is a pleasure to own. They offer an equally fine performance, with much better sound. And thanks to Sigler's arranging, I can finally enjoy this great tune, with the added benefit of great singers! The sound is rich and tuneful. Drummer Roger Fuentes (1947-2012) is practically visible on the right side, and his close-mic'd rimshots sound incredible. The sound is so good on my solid state driven HD650s, that I can't wait to hear it on my Audio Research driven Legacy speakers. My notes say "stereo excellence," and indeed it is!

Cut five is a Sigler original, and it's awesome. It's called "Do I Wanna Live My Life With You." This song picks up where the title cut leaves off. Mercy's vocals can be addicting, and on this cut the singing is nothing short of mind-blowing. Once you've hitched your wagon to Mercy's vibe, you're going to love this cut. And the sound is excellent. "Do I Wanna Live My Life With You" features that unique blend of Sigler's voice combined with his three female singers. The stereophonic landscape on my headphones is spectacular. The only sonic flaw is some tape overload at the end. Sigler's lyrics are interesting. It's a love song, but the lyrics aren't as direct as the title cut. I Googled the lyrics and discovered that reading them while the song is playing makes the song sound even better.

I wish there was a way to find out why some of the cuts sound great, while others sound merely OK. Some of the songs sound like rush-job mixes, while others are mixed to sound wide, rich, and downright incredible. What I suspect is some of the songs were recorded as a rush job, using a half inch four channel recorder. The better sounding cuts sound like they came from higher budget sessions, using a one inch eight channel recorder. It's possible that the album was recorded during a period when the studio's designer, Terry Kane, was upgrading Henry Stone's recording studio. It's also possible, and I suspect, that the better sounding cuts were recorded at Miami's legendary Criteria studios, as both producer Steve Alaimo, and engineer Ron Albert, whose names appear on the album's jacket, are famous for their work at Criteria.

My original intention was to review the Warner Brothers LP, while only mentioning the existence of the Sundi LP. However, as the title cut on the Warner Brothers LP sounded pretty bad, I chose to review the opening cut from the Sundi LP as its substitute. The two performances of "Love Can Make You Happy" are remarkably similar.

Mercy never made a second album, and that's because Sigler was drafted into the Navy right before the recording of the Warner Brothers album. When most bands would have been touring and making TV appearances to promote their record, Sigler was in the navy. By the time of his discharge, Warner Brothers, who was by then making records by edgier acts like The Grateful Dead, and Neil Young, had lost interest in Mercy. The band was dropped from the label. Such was the fate for one of the more interesting what-if bands of the late sixties.

I want to thank my friend, Mr. Gypsy, from St. Louis, who helped me with my research. Without his vast musical knowledge, an important part of this article would be missing. A few years ago he directed my attention to "Forever," which turned out to be one of best cuts on the album. Mr. Gypsy is the only person I know who remembers the original recording by the Little Dippers. I can't remember which one of us bought Mercy first, but we've been comparing our audiophile notes on this album for years. Every time one of us changes a phono cartridge, Mercy will eventually hit the platter, and one of us will call the other.

I also want to thank Jack Sigler, not only for his songs, and his superb arranging, but also for taking my call. I wish him the very best.

As an album, this title is spotty, but the best cuts are genuine masterpieces. Mercy had a vocal sound that is unlike anything I've ever heard, or ever expect to hear again. Jack Sigler wrote some songs that never made it onto this album, and he's written even more in the intervening years between then and now. He is planning to release a new album called Evolution Of Love.