Floyd Cramer (1933-1997) was one of the most prolific studio musicians who ever sat on a piano bench. During the early 60s he was a key member of Nashville's A-team of musicians who backed famous singers, such as Elvis Presley, Patsy Cline, Ray Price, Roy Orbison, Jimmy Dean, The Everly Brothers, and Jim Reeves. And that's a partial list. Cramer also made a series of successful, and well-recorded, albums of his own.

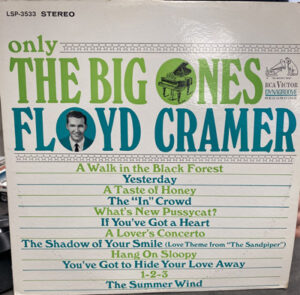

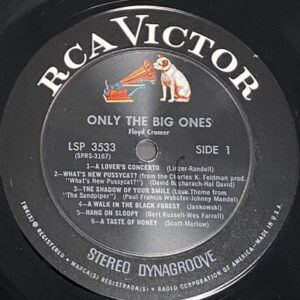

I can't remember if my first recognition of Floyd Cramer came from hearing his piano on other people's records or from hearing Only The Big Ones (RCA LSP 3533), which I bought in the late 90s. Since then I've added nine additional Cramer albums to my LP collection, but this title continues to be my favorite. His unique pianism, once you understand it, is easy to identify. Today Cramer's music is called countrypolitan, but in reality that term only applies to his work on other people's records. His own records are mostly straight ahead pop, and jazz-tinged easy listening.

Only The Big Ones was recorded in October 1965, and it was released in January 1966. As the title implies, all of the selections were hits. The album opens with "A Lover's Concerto," a song that I grew sick of decades ago. Cramer beats the original by a country mile, but my brain shuts down when I hear this melody, so I always start with the second cut. It's my very favorite Burt Bacharach-Hal David song, "What's New Pussycat." The original version, by the one and only Tom Jones, opened with a raucous tack piano, followed by the sound of shattering glass. On Cramer's version, arranger Bill McElhiney (1940-2025) substitutes the tack piano with a baroque-flavored woodwind trio. The winds appear on the right side of the soundstage. Soon the strings enter on the left. They, along with one big whack from a kettle drum (in place of the shattering glass), introduce a very confident sounding Cramer. The interplay between Cramer and the strings is a perfect example of superb music arranging. Cramer then plays skillful variations on the song's main theme. The cut features a beautiful bridge with the strings accompanied by solo flute, and the perfectly mic'd flute sounds amazingly real. In the music remaining after the bridge, Cramer shows off his innate understanding of jazz piano. If there's a better instrumental version of this song, I'd like to hear it.

Side one cut four is Jorst Janowski's "Walk In The Black Forest." I find the composer's original recording little more than sixties-era adult slime, perhaps better described as uninteresting. Cramer and McElhiney rework Janowski's music into something very tasty, and for the audiophile what they did is miraculous. The music opens with a flurry of strings, punctuated by a brush-smacked snare drum. The strings and the drummer are soon met by a delightful sounding marimba. (Brushed snare drums and marimbas sound amazing on tube gear!) There are fleeting moments when Cramer's jazzy chops remind me of Hampton Hawes, but overall the playing is simply Cramer in his element. Aside from a teensy bit of mic preamp overload on the piano, the sound is, as implied, demo quality.

Cut five is a swinging performance of "Hang On Sloopy." This is a cover of Ramsey Lewis' single, taken from the live album Hang On Ramsey! (Cadet LPS 761). I find pleasure in comparing the two pianists, as there are subtle differences in their approach to the identical arrangements. Both will get your feet moving. Need I say that both performances are indispensable?! There is, however, the sonics, and Cramer has the benefit of RCA's famous Nashville studio, and the talented Jim Malloy (1931-2018) as his recording engineer. By comparison, the Lewis recording sounds a little hollow because it was recorded, apparently, on a budget in a club. And, by the way, the club was the famous Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach, California.

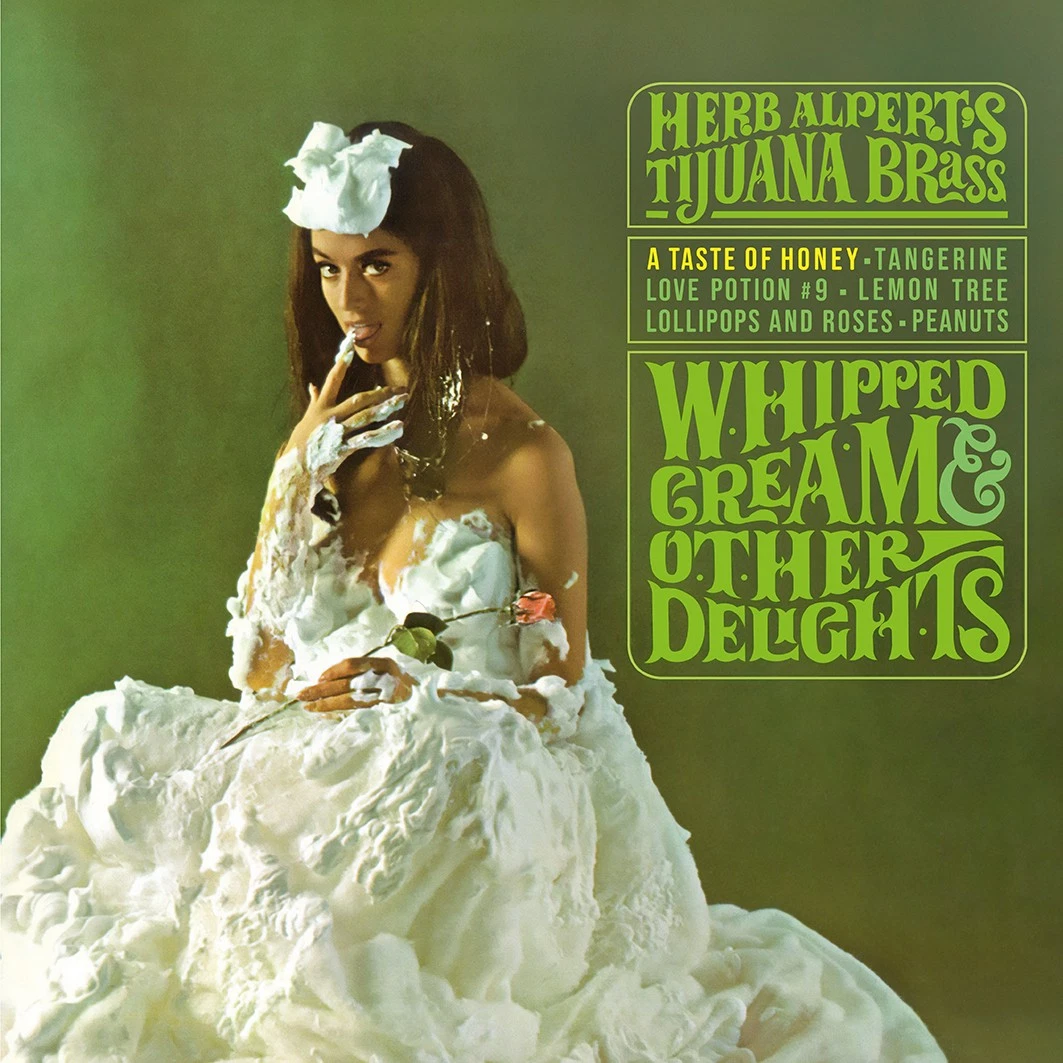

Side one closes with an excellent cover of Herb Alpert's "A Taste Of Honey." Cramer is jumping for joy, and all over the ivories. And that wonderful drummer, with his perfectly mic'd snare drum, is playing his heart out on the right side of the soundstage. I love how the drummer duplicates Hal Blaine's famous kick drum from the Alpert recording. Blaine's drum sounds a little bigger and darker, but the Nashville drum, which is just as impactful, was recorded with a better sense of room ambience.

Side two opens with Paul McCartney's "Yesterday." As it's my least favorite Beatles song, I feel no inclination to discuss it, but side two cut three is John Lennon's "You've Got To Hide Your Love Away," and that's one of my favorite Beatles songs. It's also one of the few songs that I can sing perfectly, provided I'm by myself! Joking aside, this is the most thought-provoking cut on the album. It's the kind of cut that begs you to crawl inside of it, because it's so warm and comfy. It opens with an electric guitar on the left. Winds quickly appear on the right. Soon Cramer emerges, boldly, in the middle. Once again McElhiney uses his magnificent combination of strings and winds, but this time he adds a tambourine. The interplay between the strings, the winds, and a small chorus of voices, is mesmerizing. And, of course, so is Cramer.

Side two closes with Bobby Goldboro's "If You Got A Heart," which is one of the two Goldsboro songs that I love. It's a great country rocker with a wonderfully twangy lead guitar. Cramer recreates the vocal part so well on the piano that you can almost hear Goldsboro singing the words "I'd like to know if you cry." The lead guitarist that's heard on the John Lennon song is still playing on the left side of the soundstage, and he sounds identical to the guitarist on the original recording from Goldsboro's 1965 album, Little Things (United Artists UAS 6425).

When it comes to the Living Stereo Nashville sound, no recording engineer has received more praise than Bill Porter (1931-2010), and for good reason. Porter had a unique sound, which was lush and very wide, but often with uncontrolled bass. Jim Malloy (1931-2018) had a different sound, one that was more focused and punchier in the bass. Malloy worked for RCA in Los Angeles before moving to Nashville, at Chet Atkins' behest. I can't thank Malloy enough for providing such great sound on this album. The sound is wide, dynamic, and colorful. And the instruments are perfectly focused within the stereo stage. While Cramer's piano isn't as wide as the entire stage, the tonality and the natural bite of his unique piano style is well-preserved, and smackdab in the middle. I do not know if Malloy recorded this album on a three channel 1/2" recorder, or on a four channel 1/2" recorder. I'm guessing that he had four channels, due to the complexity of the mix. Regardless of what he had access to, the stereo mix is a work of perfection.

So much has been written about Chet Atkins that it would be foolish for me to write about what's already been written by better writers than I am. He was, of course, famous for his excellent guitar playing, but he was also one of the greatest record producers of all time. Atkins was instrumental in creating the sound that is now called countrypolitan, which in reality means country music that everybody likes. He removed the fiddles and the steel guitars from hillbilly music, and replaced them with strings and lush choruses. If it weren't for Atkins we may have never known the music of Jim Reeves, Bobby Bare, Waylon Jennings, Connie Smith, or Floyd Cramer. Over my years of record collecting I've come to regard Chet Atkins as one of my favorite record producers. This album is a prime example of what Atkins, the producer, was capable of.

Floyd Cramer was one of the finest studio musicians in music history. He's been labeled a country musician, because, of course, he was. His skill as a rock and roll pianist, primarily with Elvis, Orbison, and The Everly Brothers, rivaled the Los Angeles-based work of Leon Russell and Larry Knechtel. While writing this article, I decided to revisit Cramer's easy-going piano rival, Roger Williams. Williams was a fine pianist, whose sound was closer to that of a classical musician. The problem, at least for me, is that Williams didn't swing. Cramer constantly punctuated his music with jazzy licks. Williams, at least on the records I've sampled, never did anything like that. When I hear Williams I look out into space, and there's not much to see. With Cramer my body moves. The joy that was within Cramer's playing is hard to resist. Listen to what he did on Elvis' "Devil In Disguise", and then listen to Patsy Cline's "Crazy." Cramer's piano had no limit. He also had the benefit of excellent sound. By comparison, Williams' Kapp LPs are dripping in slimy reverb. In short, Floyd Cramer was a top-notch studio musician, a concert attraction, a successful recording star, and a musical force to be reckoned with.