If you were buying music in the mid eighties, then you might remember when the music industry expected us to replace our records with "perfect sound forever" compact discs (CDs). Even though I own a lot of CDs, and I still buy them on occasion, few were ever purchased to replace the same title on LP. Truth be told, most of the music I bought during the eighties was of the second variety, and that translates into records. Sometimes I wonder what my life would be like if I had just rid myself of those pesky records when it was the hip thing to do. Well, for one thing, I wouldn't be writing this article, because I wouldn't know about the musical artist Martin Denny.

Like most gray haired vinyl-loving audiophiles, I love record stores that sell used vinyl, but even more so, I love hunting for vinyl treasures in thrift stores and at garage sales. Although records in those places have essentially evaporated, thrift shops and garage sales used to have tons of records, and the full spectrum of musical genres. In addition to the rock, classical, folk, and country records that I bought when inexpensive vinyl was so easy to find, I used to grab a type of music that's now called exotica. When you could find someone's entire classical record collection at a garage sale, you would often see exotica records in that same collection. Both appealed to people who had good taste in music, and even more so, good taste in stereo equipment. Back then the genre had no specific name. It was just Martin Denny, Arthur Lyman, and the other artists who sort-of sounded like them. I wrote about one such artist, Milt Raskin, HERE.

The kings of exotica (also referred to as lounge or Tiki music), who could also be viewed as the kings of stereophonic awesomeness, are the above-mentioned Martin Denny (1911-2005), and his former bandmate Arthur Lyman (1932-2002). I think about them every time I write for this magazine. Denny has been a frequent guest on my turntable for as long as I've had my own audio equipment, and I've known about Lyman even longer. Their music was an outlandish mashup of Hawaiian, Polynesian, South American, and Afro-Cuban music, combined with splashes of jazz. As both were part of Honolulu's bar scene in the fifties, and the release of their stereo records and Hawaii's statehood both happened in 1959, their music was originally marketed as Hawaiian music. As a young teenager, Lyman's records Taboo and Bwana Á were my favorite albums in my dad's record collection. Although both were recorded in Honolulu, neither album, nor any of Denny's (which were recorded in Los Angeles), features a ukulele or a steel guitar. Both artists used tons of percussion, and most Hawaiian records don't. Hence their music is arguably not authentically Hawaiian. However, I'm forever grateful to Denny and Lyman for introducing me to the magnificence of Hawaiian music. Today I'm focusing on Denny, only because I've owned more of his LPs. Lyman deserves a review of his own, and one is currently fermenting in my head.

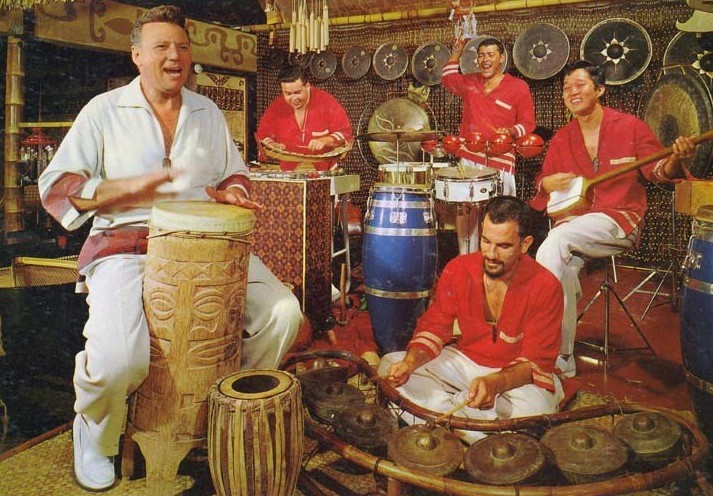

Pianist and multi-percussionist Denny, along with Julie London, Bobby Vee, and The Chipmunks, were the biggest stars during the earliest days of Liberty Records. And some of the best stereo sound ever captured on analog tape is found on Denny's albums. Liberty Records' founder Si Waronker gave Denny's debut album the title Exotica (LRP 3034), recorded in December, 1956, and released the following month. For a deeper understanding of Denny, you should know where exotica music came from. It was a 10" album called Ritual of the Savage (Capitol H-288) by Les Baxter, released in 1951. Many of the cuts on Denny's first album are covers from Baxter's album. Denny, who toured the world performing and collecting ethnic instruments from everywhere he went, reimagined Baxter's arrangements by removing the embellishments of strings and lush choruses. His stripped-down version of Baxter's music sounded more percussive, primitive, and appetizingly more ethnic. Denny's bandmates (primarily Arthur Lyman and Augie Colon) also mimicked the sounds of wild birds and they grunted like unhinged human beasts. This, along with boatloads of loads of African, Latin, and Asian percussion, primitive sounding woodwinds, and Denny's piano, made for one hell of a musical and audiophile joyride. And Liberty's vivid wide-soundstage stereo sound benefited from scant amounts of reverb, making the music sound immediate, impactful, and most of all believable. In short, Denny and recording engineer Ted Keep created music and recordings that still have the power to turn mild-mannered audiophiles into vinyl-addicted, tube-rolling, cable-swapping cavemen.

I fondly remember the first time I spun a Denny record. It was 1986, and the album was The Versatile Martin Denny (LST-7307). My audio system consisted of a Luxman PD289 turntable, a Grado F1+ cartridge, and a low-powered (seven watts per channel!) Nikko receiver driving Infinity ES1 electrostatic headphones. I miss that system. And I miss how it sounded on percussion. With this early sixties LP the sound from coming out of those insanely good headphones was like sitting on the studio floor surrounded by live musicians. However, even more interesting was that this guy, Denny, sounded just like Arthur Lyman. I soon learned that it was sort of the other way around.

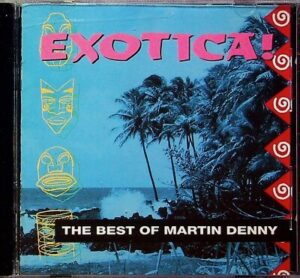

The CD I'm reviewing is called Exotica! The Best Of Martin Denny (Rhino R2 70774). Although I currently own five Denny LPs (I used to own twelve), when I need a Denny fix I mostly reach for this disc. It also provides me with something that every audiophile needs: A realignment of my sonic judgment. There are days when I don't know if my finicky audio system will please my even finickier ears. Even though my mood is usually the culprit rather than dirty electricity, this disc has helped me through some rough times. The sound on selected cuts is stellar, and the music makes me happy. In other words, it's like having an audiophile reset button. Also, two of my friends are trapped in the HiFi jungle. They are hooked tweaks. Be it power cords, digital cables, DACs, fuses, interconnects, wall sockets, or the aftermarket feet under their components, these two cavemen are constantly screwing up their sound. And when everything sounds like dreck, who do you think they call? They call me, but not before they make things even worse by seeking advice from ChatGPT. I don't whip out a phone to fix a stereo. I use hard-earned experience and great sounding albums. This CD (along with some vintage Willie Nelson) is a perfect tool for fixing the damage caused by audio savagery. I should mention that this isn't the only Denny CD that's available; it's just the one I own.

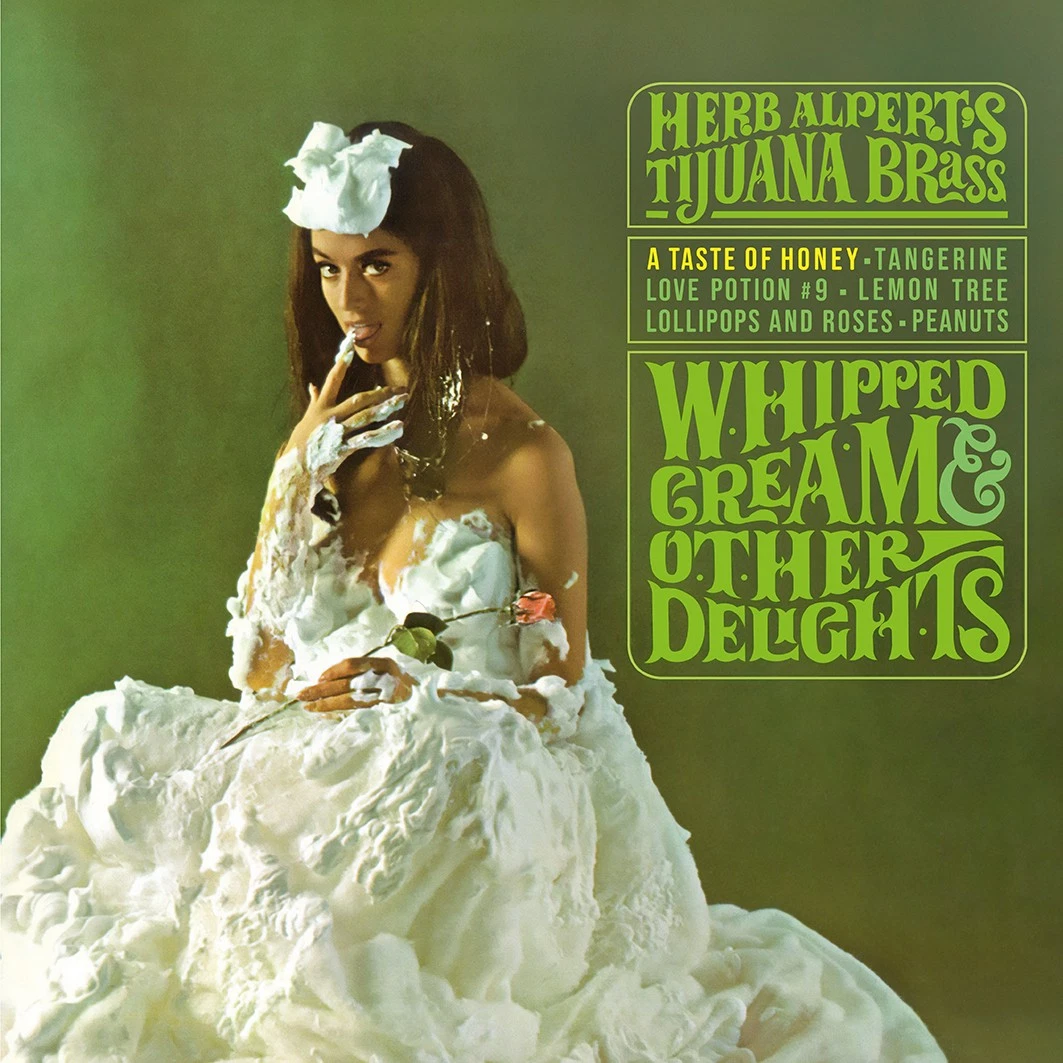

The members of Denny's group in 1956 included Denny on piano, Lyman on vibes, John Kramer on bass, and August (Augie) Colon on congas, bongos, and whatever else he could bang on. By 1957, Lyman had left to form his own group, and he took Kramer with him. Future Tijuana Brass member Julius Wechter was Lyman's replacement. Kramer's replacement was Harvey Ragsdale. As every member was a multi-percussionist, their combined percussion was an important part of the Denny sound.

The CD opens with Denny's famous redo of Les Baxter's "Quiet Village," the single that spawned the entire exotica movement. The cut opens with the scraping of a grooved cylinder to mimic the sound of a croaking frog. This is accompanied by a crude-sounding wooden flute which acts as a warning that danger is just around the corner. Following the flute are Denny's piano and a plethora of indescribably wild sounding instruments. Soon a flesh-eating jungle bird (voiced by Lyman) enters. He's telling you to go away, but you can't stop yourself from going deeper into the rainforest. From this point on you're lost and there is a feeling of imminent danger caused by Denny, who is now playing the main theme on his piano. We're at the seven second mark, and you meet face to face with that wild and crazy beast Colon, and he's playing a djembe, making the music even more menacing. And, by the way, these musicians sound hungry for human meat. Although you fear for your life, you are compelled to turn the volume up to eleven, because you're under a wicked spell. At one minute and forty seconds, as you go even deeper into the forest, Lyman enters with his shimmering vibes. The music works like a drug. You can't turn back! After three minutes and forty one seconds, you suddenly wake up and realize that all that you've been experiencing is a mono recording from 1956.

Cut four is "Love Dance." It's another piece of music lifted from Ritual of the Savage, and two things are prominent: Denny's piano and the pounding of a large drum in the back of the room. Perhaps the drum isn't really in the back of the room, but that's the way it sounds on this remarkably good mono recording. A closely mic'd maraca is also heard, as are Lyman's vibes, and Colon's savage howls. Is this deep music? Hell no! And you don't care! Also, here's proof that a mono recording can portray a sense of depth. The deep bass provides the music with its size, and the clever mic placement, courtesy of the great engineer Keep, allows for the sound to have a sense of depth.

The rest of the cuts in this review come from Denny's post-Lyman period. When Wechter replaced Lyman, the sound of the band changed. As colorful as ever, the band's haunting sound became whimsical. Another big change was the benefit of stereo recording which the band and the recording engineer took full advantage of. By this time, Denny had collected even more exotic instruments, and he used them to create spectacular sounds. I could have easily picked more cuts to comment on, but I stuck with my favorites.

Cut eleven, which comes from the 1959 album, Afro-Desia (LST 7111), is one of my two favorite cuts on the CD. It's called "Tsetse Fly." I have no idea what the deadly tsetse fly sounds like, and I hope that I'm never close enough to one to find out. The cut opens with a didgeridoo on the left side, and it sounds awesome due to its deep bass. This is quickly followed by the sound of a large flying insect. I think it's the air being leaked out of a balloon, but it sounds great. In three seconds comes some impactful percussion. The percussion includes a huge bonk from a large leather-headed drum on the right, and Wechter's marimba on the left. Soon we get more of that big drum, and congas in the middle. Are you drooling? Good, because I am! At this point the band breaks into a jam, and Denny is having a ball on his piano. I don't know if Wechter brought two marimbas to the session, or if Ted Keep panned him to the right. Or maybe there's a second marimba player, which knowing these guys is quite possible. I don't care that the music isn't deep, because it's so much fun, and so is the demo sound. This is a generous dose of crank-it-up goodness.

Cut thirteen is another cut from Afro-Desia. It's called "Simba." The cut opens with three ultra- ripe-sounding thuds from that same big drum, but this time it's in the middle, and the drums' head sounds looser. (The room must have been cooler.) At the four-second mark, the didgeridoo returns to mimic the sound of a roaring lion. And again, we're lost in the forest, and we're surrounded by cavemen, who just happen to be skilled musicians. The sound they're creating is filled with countless colors and the dynamic range is huge. We even get to hear them chanting. And the reason is because they captured a girl, and she's chanting with them! There's so much percussion and rapid changes that it's impossible for me to keep track of the instrumentation. And, by the way, those flesh-eating birds are back, and they brought with them some monkeys. This is musical mayhem, and the sound will blow your mind! Can you imagine what it's like to be surrounded by musical instrument-playing men wearing loincloths? You're being cooked and served with boiled carrots and potatoes, and you don't even care. As the cut closes the tempo increases to a wild pace, because this is a celebration of an upcoming feast. Please make sure that I'm served with only the finest of dark ales, thank you.

Cut fourteen is "Aku Aku," also from Afro-Desia. Denny's band is performing a sacred ritual for us audiophiles, and they're doing it with help from studio percussionists, as it would be impossible for four musicians to create something that sounds this massive. I'm way over my head in my ability to describe this cut, but it's the most impressive cut on the disc. You need to hear it to believe it. This is one of the greatest percussion ensembles ever recorded on analog tape. Holy Indonesian ritual, Batman! This cut features vibraphones, xylophones, congas, and gamelan gongs.

I love to finish evenings with Martin Denny by playing cut fifteen. It's called "Martinique," and it comes from the album Quiet Village (LST 7122), which is also where you can find the stereo rerecording of its title cut. It's mellow, melodic, and it has a lot more reverb than the previous cuts. It's not really a demo cut. It's just a great way to cool down after the intensity of "Aku Aku."

Perhaps it's strange that in the first paragraph I was slightly dismissive of CDs, and yet, here I am praising a CD. I have nothing against CDs, and, frankly, it's been a long time since I did. I'm behind any digital format that's used to capture and preserve the unvarnished truth. Denny's recordings are prime examples of tube era stereophonic sound. The musical colors are fully saturated, and the air between the instruments is what we audiophiles love. The recordings don't need fixing; they just need preservation. Having said this, I know from a recent response to one of my reviews, and from a similar response from one of my colleagues in the Las Vegas Audio Society, that some people would like me to review streamable albums. I don't check to see if albums are streamable, but I know that Martin Denny's music is.

The only concern I have with digitized Denny that's newer than this 1990 CD is this: Many mastering engineers treat old analog recording as flawed. Flaws are supposed to be fixed, right? The result of this "fixing" is that much of Denny's music, or at least most of what I found on Youtube, includes heavy-handed de-noising. And I fear that this is what Warner Music Group now deems as releasable. If you don't play CDs or records, your only choice is what's currently available for streaming. I don't know if streaming provides access to the earlier and less-doctored transfers of Denny's music. My use of the word "doctoring" refers to the de-noising process. It's a great tool for cleaning up excessively hissy tapes, which Denny's tapes are not. It's also good for cleaning up noisy transcription discs when no tape exists. It's been my experience that too many mastering engineers use de-noising when it's not even needed, or they use it too heavily. What does de-noising abuse sound like? It sounds airless, ambience is thickened, and to end air is absent. For sure, the noise floor is always low, but so is the sense of realism. De-noising, like its cousin digital reverb, leave in their wake a synthesized substitution of the source's top end. And the better my audio system gets, the more I hear a gelatinous, airless mess on CDs that used to sound acceptable. De-noising isn't exclusive to CDs and YouTube. It seems to be around every corner.

To my fellow LP collectors, I think it's important to mention that there are two different versions of the album Exotica. Although the tunes are the same, the mono version is the original album from 1956. It's also the album that I take a little more seriously, and, based on my research, so did Denny. The stereo rerecording is from 1959, and the cover photo, featuring the lovely Sandy Warner, is the same. And they both have excellent sound.

Lastly, I think I've made it clear that I'm crazy about this CD. I couldn't imagine having a music collection without it.