Arlester "Dyke" Christian—along with James Brown—was almost singularly responsible for the infusion of Sixties funk and soul into rap music in the late 1980s. Yet ask the average man on the street about Dyke & the Blazers, and you'll generally be greeted with a blank stare in response. One of Dyke's biggest hits, "Let a Woman Be a Woman, Let a Man Be a Man" was one of the earliest tracks whose breaks would be sampled by some of the key figures in hip-hop including Public Enemy, Tupac, Cypress Hill, and Stetsasonic. Rap musicians liberally harvested from his catalog, sampling such tracks as "Funky Broadway," "We Got More Soul" and even the ballad "I'm So All Alone." Unlike James Brown, however, Dyke only enjoyed an intermittent flow of chart success, initially with "Funky Broadway" in 1967, which made it to No. 17 on the Billboard R&B Charts. Wilson Pickett was so taken by the infectious riffs of the tune that he simultaneously recorded his own version, which eventually went to No. 1 on the Billboard R&B Charts. Early on, "Funky Broadway" was a little bit of a sticky wicket for radio station programmers nationwide; this marked the first time the word funky had appeared in a song title, and there was some aversion to the use of the word. Some radio stations actually refused to play it because they felt that "funky" was offensive.

Dyke grew up in the Buffalo, New York, area, and played bass in a local bar band, Carl LeRue and his Crew. In 1964, LeRue received an invitation to bring his band to Phoenix, Arizona, to become the backup band for a new vocal group, The O'Jays. Dyke went along for the ride, but it ultimately didn't pan out, as The O'Jays headed to the east coast to find success, and LeRue and several members of his band headed back to Buffalo. Three members of the band, including Dyke, his childhood friend and guitarist "Pig" Jacobs, and saxophonist J.V. Hunt, had no means to travel, and decided to stay in Phoenix. Soon they teamed with another local band, The Three Blazers, and later added a dedicated bass player, which freed Dyke to concentrate on vocals. They re-emerged as Dyke & the Blazers, and in no time at all, had put together the basic structure for the tune "Funky Broadway," which became a big local hit in Phoenix. There's a fair amount of speculation as to whether the "Broadway" in the song refers to Broadway in Buffalo, or Broadway Road in Phoenix, a rough part of town which Dyke had developed a certain affection for.

The band was approached by local music producer Alvin Battle, who recorded "Funky Broadway" in his own Audio Recorders Studio in Phoenix, and on the success of the single, the group toured extensively. Dyke had even created a series of dance moves on stage for the song, and the band managed to get booked for a series of engagements at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. Unfortunately, the stress of playing those dates—and of touring in general—split the band, right about the time Wilson Pickett's version of "Funky Broadway" hit No. 1 on the R&B charts (it even reached No. 8 on the more mainstream Billboard Pop charts). With the dissolution of the Blazers, Dyke retreated to hometown Buffalo, but got a call in 1968 from record producer Art Laboe to come to Los Angeles and make records at his own Original Sound Studios in Hollywood.

In Hollywood, Dyke played with a group of studio musicians known as the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band. He was hesitant at first, but soon discovered that the group of studio players was top notch, and they quickly developed a consistent rapport. During a half-dozen studio sessions that were scattered over a period of not quite three years, enough tracks were recorded to fill out a couple of LP's worth of 45 rpm singles. And resulted in some of Dyke [& the Blazers] biggest hits, including "Let A Woman Be A Woman, Let A Man Be A Man," which reached No. 4 on the R&B charts, and No. 36 on the Pop charts. Those sessions also generated "We Got More Soul," which reached No. 7 on the R&B charts, and No. 35 on the Pop Charts. The Watts band played on all the recordings, and even though Dyke Christian was the only true remaining member of the Blazers, Art Laboe had all the 45's labeled for release by Dyke & the Blazers.

While preparing for a tour of England intended to bolster his popularity, and during a visit to Phoenix in 1971, Dyke was gunned down by another addict in an apparent drug deal gone wrong. He'd been using for years, but was so secretive about it that no one around him was aware of the extent of his drug habit, despite his increasingly erratic behavior. He was only 27 years old—and unfortunately another casualty of the infamous "27 Club." While definitely little more than a footnote to the funk and soul music of the period, the importance of Dyke's influence on future generations cannot be overstated. At the time of his greatest success, Dyke was considered by James Brown to be a serious rival, and funkster Rick James described Dyke's music as "revolutionary." Serious collectors know how devilishly difficult finding original sides by Dyke & the Blazers can be; these two new LP compilations from Craft Recordings document the importance of Dyke's contributions to both funk and proto-funk.

Dyke & the Blazers: Down on Funky Broadway: Phoenix (1966-1967)

To quote from Alec Palao's liner notes for the album, "Funky Broadway" was amongst the first records to bring the unabashed grit of the ghetto into the charts and thus the national consciousness. The unique noise that Dyke and the players developed...was unaffected and real. It projected in sound the same sort of statement that their raw-voiced frontman, in his evocative description of the street and its importance to the black community, was making. Dyke's metaphor of Broadway, and its "dirty, filthy" ennui, was entirely appropriate—this was dirty, filthy music, and soulful to its core.

"More importantly, what "Funky Broadway" did was, for perhaps the first time in a bona fide hit record, render down the groove to a veritable nub, laying bare its hypnotic, trance-like effect. This was not the slick rhythmic conveyor belt of Detroit and Chicago or the supple ensemble style of Memphis and Muscle Shoals. Instead, we experience a graceless beat that almost seems to celebrate its very crudity. It was the sweaty bandstand at the Elks Club in Phoenix, or any other black niterie around the U.S. for that matter, decanted straight to vinyl. And let's not forget that title. At the time, "funky" was still a difficult word for the general population, even if it was a staunch part of the black musicians' vernacular."

Dyke Christian wasn't a particularly eloquent or inventive lyricist, and he didn't possess the vocal finesse of some of his contemporaries. Through most of the runtime of "Funky Broadway" (Parts 1 and 2), he grunts, groans, and screams the tried and true devices of calling out every major music city in the US, as well as nods to other popular black performers. And he constantly is reminding the listener that this is his breakthrough hit; all these devices were intended to be ploys to improve the possibility that more radio stations would air the song and increase the band's sales. In fact, at intervals throughout the compilation's four sides, frequent references are made to "Funky Broadway." It may not be the most creative approach, but when you take into account the undeniably infectious grooves of the tune, it was definitely the smart move.

Even songs like "Swamp Walk" with its really hip horn breaks and "Swamp, swamp, swamp, swamp...walk" vocal refrain manages to squeeze in a nod to "Funky Broadway." "Uhh," which is a not-too-subtle booty call, has a really propulsive beat, along with a great guitar break from "Pig" Jacobs and those horns just never stop throughout the songs' six-minute runtime. "Why Am I Treated So Funky Bad" is an extended blues where the rhythm section lays down this totally delicious groove that just lopes along for most of the song's duration, as Dyke vocalizes about how badly he's been treated. The tune is punctuated with trumpet and sax breaks, then the entire cast joins in for the vocal chorus; this is definitely one of the album's highlights.

Dyke & the Blazers: I Got A Message: Hollywood (1968-1970)

When Art Laboe brought Dyke to Hollywood to record in 1968, Dyke wasn't too keen on Art's insistence that he work with the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band in the studio, but he eventually came around. And the results were nothing short of astounding, especially when compared to the more rough-hewn sound of the Phoenix recordings from just a year or so earlier. Dyke developed a good rapport with the Watts Band, and they played off each other musically to very good effect, and Dyke often sang live with the band. And that direct-to-tape live quality gave the songs a vibrancy and immediacy that overdubbed vocals just couldn't match.

I Got A Message: Hollywood (1968-1970) collects singles and unreleased takes from the three year period of recordings made in Art Laboe's Original Sound Studios. Shockingly, only about a half-dozen recording sessions took place within that span, but the quality of the tapes speaks volumes of the sympatico that Dyke and the Watts band achieved while there. They churned out singles like 1967's "So Sharp" and 1968's "Funky Walk," which both landed on the Billboard R&B charts. But they scored even bigger hits in 1969 with "We Got More Soul" and "Let a Woman Be a Woman—Let a Man Be a Man," with both tunes breaking into the Billboard R&B Top 10 and the Pop Top 40. And the funk kept coming, with the propulsively swinging "Uhh" in 1970, followed by an inspired rendition of "You Are My Sunshine" that was simultaneously searing and soulful.

The sky seemed like the limit, and Art Laboe still laments the fact that Dyke's immense talent and charisma was never given the opportunity to truly shine on a national level. Dyke's inability to make himself consistently available in the studio seriously limited the ultimate impact he might have had, and his deepening drug addiction and constantly unpredictable behavior were his ultimate downfall. Regardless, the tracks in this excellent compilation prove testament to his immensely influential talents as a singer and performer.

Listening

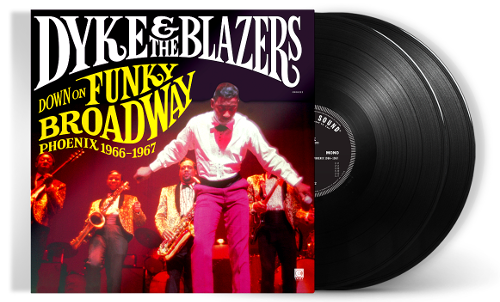

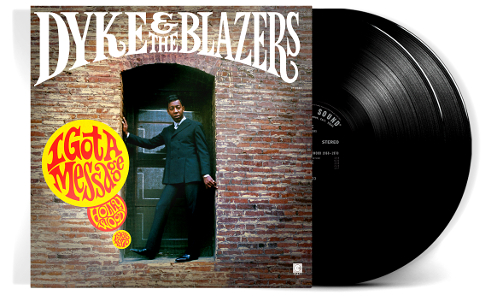

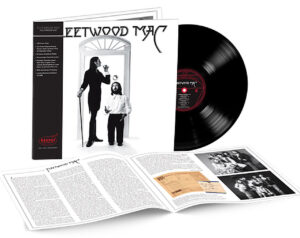

Down on Funky Broadway: Phoenix (1966-1967) was recorded in mono, and the pair of LPs is presented in glorious wide mono. By the time Dyke & the Blazers recorded I Got A Message: Hollywood (1968-1970), stereo was all the rage, and the pair of LPs is presented in superb Sixties stereo sound. Both LP sets were remastered (and in the case of I Got A Message: Hollywood (1968-1970), remixed) by Dave Cooley at Elysian Masters from the original tapes. The LPs were pressed by MPO in France; the disc surfaces were exceptionally glossy, and all arrived perfectly flat.

Each two-LP set is about as perfectly realized as seemingly possible. The double gatefold LP jackets are tip-on style on heavy paperboard, and the LPs are housed in deluxe rice paper-lined inner sleeves. Multi-page booklets included with each set feature extensive (and rare) images of the band and a variety of memorabilia, with new liner notes from Alec Palao (producer for each set). Each booklet includes oral histories and archival interviews with band members and other key players, including manager Art Barrett, and legendary radio personality Art Laboe, who released Dyke & The Blazers' music on his Original Sounds label.

My listening was done through very different setups this time around. The mono LPs were played using my Rega P2 turntable, with Rega's RB 250 arm, modded with the Michell Technoweight/Stub and Rega glass platter upgrade with ProJect leather mat. The arm was equipped with an Ortofon 2M Mono cartridge, and the mono signal was fed into a Sutherland KC Vibe Phono Preamplifier. The stereo LPs were played using my ProJect Classic turntable fitted with a Hana SL moving coil cartridge, with the signal fed into a Musical Surroundings Phonomena II+ phono preamp that's powered by a Michael Yee linear power supply. The output signals of both turntables were fed into a new setup (that's in for an upcoming review) featuring a Wells Audio Commander tube preamplifier and the Wells Audio Inamoratta II solid state power amplifier. Those drove my Magneplanar LRS loudspeakers, which were supplemented with dual subs from Definitive Technology and REL.

With regard to the sound of Down on Funky Broadway: Phoenix (1966-1967), I'm a firm believer that mono LPs should only be played with a true mono cartridge. Fortunately, I have a perfect setup with the Rega table and the Ortofon 2M Mono cartridge; the stylus geometry of the Ortofon cart is such that it rides the mono grooves more perfectly than a stereo cartridge can. Resulting in a greatly improved presentation of sources recorded in true mono versus how a stereo cart interprets that same information. The sound quality was never less than superb on the mono LPs, with a broad and deep soundstage and virtually no trace of any groove modulation noise. The pair of mono LPs from MPO were among the finest mono sound I've experienced in my system. I also downloaded the digital files for this title, but in terms of sound quality, they were handily bested by the LPs played via the Ortofon 2M Mono cart.

The stereo sound of I Got a Message: Hollywood (1968-1970) was also absolutely superb; while the mono LPs are rendered with shocking realism, the stereo spread broadens the soundstage and definitely improves image localization. The stereo LPs also exhibited very little groove modulation or any noise of any kind—these are remarkably quiet pressings, which has been my overall experience with anything from MPO.

Arlester "Dyke" Christian lived a tragic life; his band's failure to achieve a major level of success and his struggles with addiction were unfortunately very commonplace in the music industry at the time. His untimely death in 1971 cut short what could have been a very promising career, but his influence on a generation of funk and rap musicians is made clear in this excellent pair of compilations from Craft Recordings. Fans of great Sixties funk-and-soul will really enjoy these records, and from a historical standpoint, they're indispensable. Highly recommended!

Dyke & the Blazers: Down on Funky Broadway: Phoenix (1966-1967). Two 140 gram black vinyl LPs: $29.99 MSRP.

Dyke & the Blazers: I Got a Message: Hollywood (1968-1970). Two 140 gram black vinyl LPs: $29.99 MSRP.

Available from Craft Recordings.

All images courtesy of Craft Recordings.