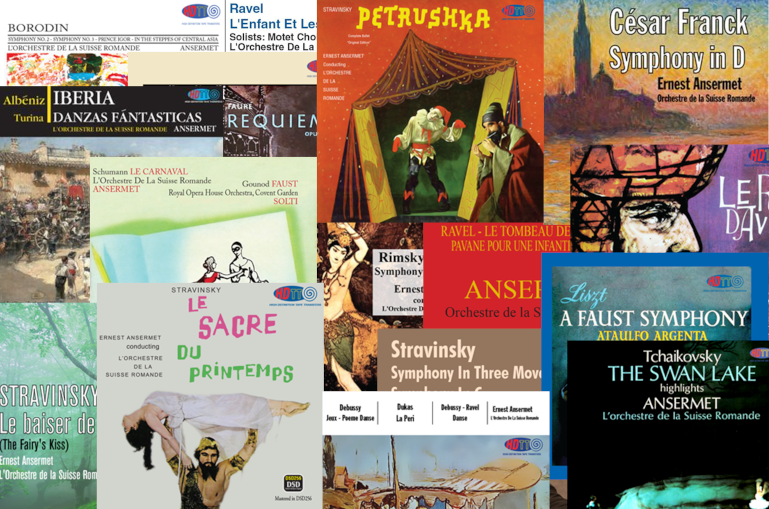

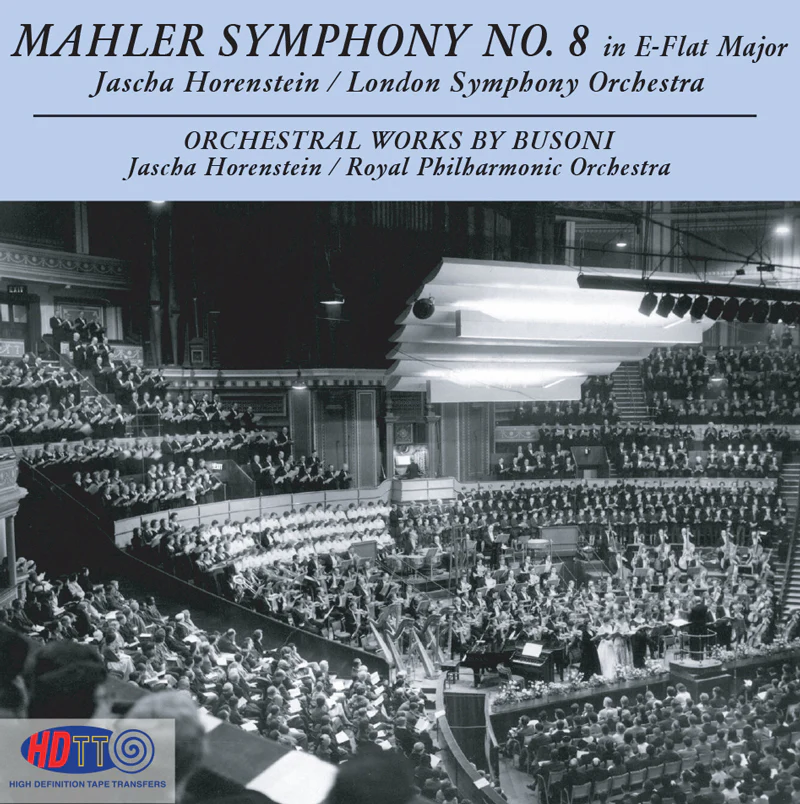

For anyone who values the early Decca sound, High Definition Tape Transfers is a treasure trove of music to explore. Here I'd like to share with you some of the outstanding recordings made by Decca's recording engineer Roy Wallace between 1956 and 1961. My hope is to give you a start to your own explorations of this marvelous catalog.

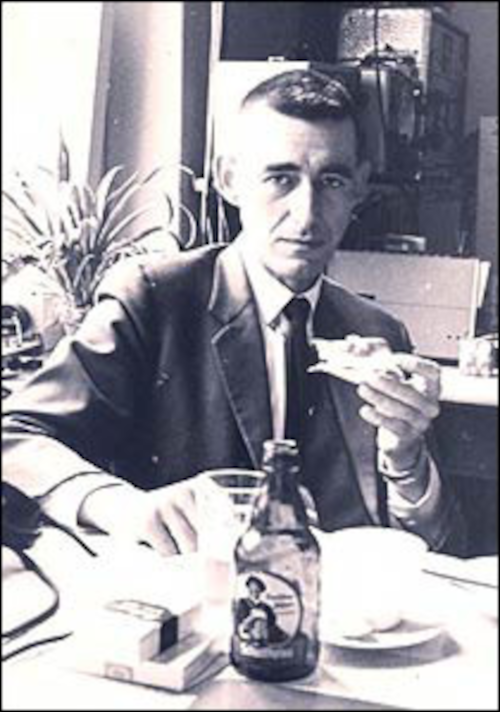

I've written previously about the wonders of the HDTT catalog for uncovering DXD and DSD256 downloads of some of the great recordings of the golden era of stereo recordings (HERE). And I've also written about the recordings engineered by Decca legend Kenneth Wilkinson that one can find at HDTT (HERE). In this article, I'd like to talk about the Decca recordings engineered by one of the early pioneers of stereo recording, Roy Wallace (1927 - 2007), who engineered many of Decca's classic recordings in Switzerland and Italy.

Roy Wallace. Photo courtesy Discogs

It was the collaboration of Roy Wallace, Kenneth Wilkinson, and Arthur Haddy that developed the Decca Tree spaced microphone array for stereo recording in the early 1950s (Wikipedia). Wallace made the earliest session recordings using the Decca Tree in Victoria Hall in Geneva in May and June 1954 (Rimsky-Korsakov's Antar, Ansermet conducts Glazunov Balakirev & Liadov; Decca Discography, p.34).

When this technique was first used by Roy Wallace in 1954 in Geneva, the microphones were Neumann cardioid KM-56s, tilted 30 degrees toward the orchestra. In short order, other microphones were tried including the cardioid M-49 (in baffles), omnidirectional KM-53, and the omnidirectional M-50 which Kenneth Wilkinson championed and which ultimately became the standard mike for the tree beginning in 1955. In Wilkie's opinion, the KM-56s, were not the way to get the best possible sound. "The 56 naturally gave a good stereo effect," he notes, "but I was never happy with the quality of the sound. I don't think a directional mike gives you a good sound from an orchestra anyway. It's very good on solos and solo work, but I don't think it is for orchestral." (Michael Gray article, see below)

But on the continent, Roy Wallace continued to employ his cardioid M-56 microphone array through at least 1959 (to my great joy), and it is with this array of cardioid microphones that many Ansermet recordings were made. To my ears, Wallace was onto something that Wilkinson dismisses too easily: a very precise stereo image with excellent capture of front-to-back depth in addition to lateral placement. And, while Wallace was also to gradually add outriggers to capture more details, it is this precise stereo image that has always attracted me to these early recordings made by Roy Wallace. So let's talk about a few...

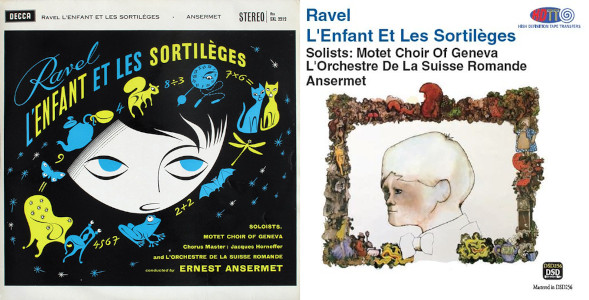

Original cover on the left, HDTT cover on the right

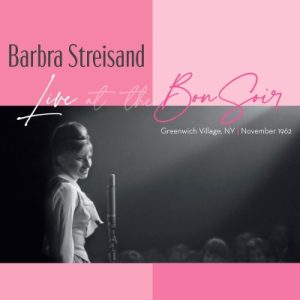

Ravel: L'enfant et les sortilèges - Ernst Ansermet, l'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. 1956 (PureDSD256) HERE

I've written before about this recording (original cover on the left, HDTT cover on the right) and rather than repeating myself, I encourage you to take a look at this earlier article. Suffice it to say, the recording is a real test of the resolution, accuracy, and transparency of one's system—I am blown away each time I listen. To clearly resolve the interplay of the instruments with each other and with the vocalists presents a real challenge; it takes quite a bit transparency in one's own system to cleanly articulate all that is going. It is available from HDTT in an excellent Pure DSD256 transfer from a 15ips two track tape.

Stravinsky: Le Sacre Du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) - Ansermet, l'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. 1957 (PureDSD256) HERE

At the dawn of stereo recording "le Sacre" was represented by three recordings: Ansermet with the OSR, Monteux with the Paris Conservatoire (both recorded by Decca teams), and Markevitch with the Philharmonia by HMV. While the OSR doesn't have the power of Markevitch's orchestra, what they do provide is a satisfyingly lean, tough, sinewy performance. "Wiry" comes immediately to mind. The distinctively astringent sound of the OSR's woodwinds fits well as they play well beyond their reputation. But it is the excellence of the sound quality that always strikes me; it perfectly matches the performance: detailed, precise, impactful, with striking transparency and superb inner detail. Available from HDTT in a PureDSD256 transfer.

Stravinsky: Le Sacre Du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) - Monteux, The Paris Conservatoire Orchestra. 1957 (DXD) HERE

This Sacre was also recorded by Roy Wallace and the Decca team in 1957, but here the recording is with Pierre Monteux in Paris and on contract for RCA. Different hall, different orchestra, different conductor, but the same recording engineer and technology being applied. Results? To my ears: the same soundstage, resolution, and detail; a bit of tape overload on climaxes; a warmer, richer sounding recording hall with bloomier bass; a different interpretation by the performers. Not as driving, not as "barbaric" as the Ansermet/OSR interpretation. I vastly enjoy both recordings. How could one be without the modern recording by the conductor of the original 1913 performance? This time HDTT has resorted to transferring in PCM at 24-352.8, presumably because the source tape was not in sufficiently good condition to allow a straight DSD256 transfer.

Faure: Requiem - Gérard Souzay, Suzanne Danco, Ansermet, l'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. 1955 (PureDSD256) HERE

Ansermet's recording of the Faure Requiem has both admirers and detractors. The Penguin Guide calls it "technically immaculate…sympathetic and stylish performances [of the orchestral works], highly regarded in their day and still sounding well." Gramophone says, "Gerard Souzay sings the baritone part most beautifully and for this, and for Ansermet's grave and distinguished treatment of the lovely work, the reissue is most welcome…In almost every respect an ideal performance."

BBC Music Magazine is less kind, but when reviewing a competing performance allows that, "The conductor Ernest Ansermet could claim an involvement with the musical life of Paris from the earliest years of this century, so his 1955 Decca recording of Fauré's Requiem has at least the stamp of authority. You can feel it in his bold colours, keen articulation and generally robust approach to work that many conductors choose to swathe in pastel-shaded cotton wool. You have to put up with tape hiss, warbly choristers and a soprano instead of a boy treble in the 'Pie Jesu', but it is worth it to avoid the lugubrious mellifluity of (conductor not to be named here).

The reviewers at MusicWeb (HERE and HERE) basically wish they'd not been forced to listen to it, one commenting, "Even Ansermet's most devoted acolytes would be hard pushed to defend the performance of the Requiem enshrined in this Decca Eloquence disc. Admirer of the conductor though I am...I'm afraid that there is little to salvage from the recording other than the singing of Gérard Souzay."

For the record, I'm with Gramophone on this performance. There are perhaps others that I would place higher on my list of preferred performances (e.g., John Rutter's supremely musical, beautifully balanced reading on Collegium), but I would never kick this recording out of my library notwithstanding its rather over-reverential pacing.

To the matter at hand, however... The reason for mentioning this recording is the sound quality captured by Roy Wallace in this recording from 1960. It is top notch, with an almost perfect capture of the soloists and choir. Once again, Wallace is capturing this performance using his coincident KM-56 microphones in the classic Tree configuration and the sound is focused, detailed and with excellent depth of field. As a further bonus, HDTT is once again able to give us a direct DSD256 transfer from a 15ips two track tape, with excellent transparency.

Debussy Jeux - Dukas La Péri, Ansermet, L'Orchestre De La Suisse Romande. 1958 (DXD) HERE

Debussy wrote his last ballet and last orchestral work, Jeux, (or Games) for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballet Russe, with Vaslav Nijinsky as choreographer and lead dancer. The first performance puzzled its audience, and as it took place only two weeks before the tumultuous premiere of Stravinsky's Le sacre du printemps, it was nearly forgotten in the uproar. But Jeux was every bit as revolutionary and forward-looking as Sacre and even more daring harmonically. Debussy's most nearly atonal work.

And as the last piece on the album Decca has juxtaposed Dukas' final significant work, the 20-minute ballet La Péri, his most Impressionistic score. The juxtaposition of the two one of the reasons I enjoy this album so much, musically.

Of course, the other reason I return time and again for a listen is the pure luxury of the sonics once again captured by Roy Wallace (way back in 1958) with his Decca Tree setup. As with the other albums I'm highlighting for your exploration, the orchestra is captured with excellent stereo spread, pinpoint localization of instruments, and with utter transparency. It simply punches all of my little audiophile fanatic buttons.

Tchaikovsky The Swan Lake Highlights, Ansermet, L'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. 1958 (DXD) HERE

Wonderful sound, excellent transfer, great performance. What more to say? Ansermet is a master of these ballet works. This recording needs to be in one's collection no matter what other fine recordings one may have of this work. (The other must have recording is Ansermet's Royal Ballet Gala Performances recorded in 1959 by Kenneth Wilkinson in Kingsway Hall, perhaps even better sonically and also available from HDTT; discussed earlier HERE.)

Ansermet conducts Honegger & Ravel, Ansermet, L'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. 1960 - 1963 (DXD) HERE

Ansermet was an indefatigable advocate for the Swiss composers Arthur Honegger and Frank Martin. He conducted first performances of many of their works, and Honegger's Pacific 231 (heard here) was dedicated to Ansermet.

Honegger's Symphony No. 2 is a war symphony, begun in 1937 but with interruptions not completed until 1941. It charts the same course as Beethoven's Fifth, the course from darkness to light. Opens with a weighty Molto moderato wrenched into a bludgeoning Allegro, moves through a "somber, not to say, at times, positively hopeless" Adagio mesto, and ends in a climactic Vivace non troppo—Presto. A completely engaging and thoroughly compelling work that I return to regularly. The Pacific 231 sounds as if it depicts a steam locomotive, an interpretation that is supported by the title of the piece. Honegger, however, insisted that he wrote it as an exercise in building momentum while the tempo of the piece slows. An interesting work that was written as the first movement of his third symphony, but now most commonly performed independently of the remainder of the symphony, as here.

Le Tombeau de Couperin is a suite for solo piano by Maurice Ravel, composed between

1914 and 1917, heard here in the orchestral version produced by Ravel in 1919. Written after the death of Ravel's mother in 1917 and of friends in the First World War, Le Tombeau de Couperin is a light-hearted, and sometimes reflective work rather than a sombre one which Ravel explained in response to criticism saying: "The dead are sad enough, in their eternal silence."

So what about the sound quality on these recordings? Oh yes, the sound quality is all sublime goodness. By 1960, Wallace was fully capturing the weight and body of the orchestra as well as the soundstaging, detail and transparency. There is some tape overload on orchestral climaxes (notably the very end of Pacific 231), but otherwise the sound is just lovely. Very much recommended.

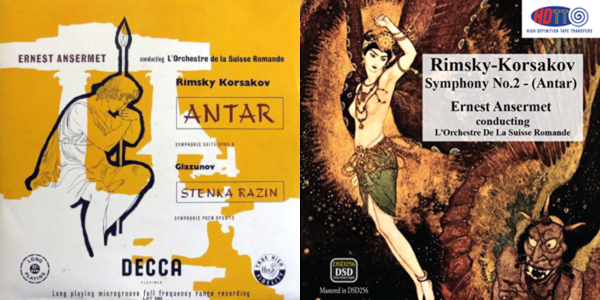

The cover on the left is the original release from the mono recording team because no stereo SXL was issued—Decca deeming the recording to be experimental, the stereo tape just went into the vault.

Rimsky-Korsakov Antar, Ansermet, L'Orchestre De La Suisse Romande. May 1954 (PureDSD256) HERE

And come we now back to the first of Roy Wallace's regular session recordings, from May 1954, the Rimsky-Korsakov symphonic suite Antar. As David Hurwitz writes in Classics Today, "How nice to see Ansermet's Antar, Decca's first official stereo classical recording, back in the catalog. It remains in a class by itself interpretively, and the 1954 sonics still sound remarkably good, if slightly thin. Right from the opening, with its punchy accents from the bassoons, you can tell this performance is going to be special, and so it proves. Ansermet's fluid tempos and crystal clear balances conjure up the perfect fairytale atmosphere, whether it's in the first movement's graceful second half, the exciting ensuing “Anger” movement (that in its intensity and bravura cleverly disguises the rudimentary nature of Rimsky's counterpoint), the colorful third movement march, or the luscious slow finale. The orchestra itself is on its best behavior."

As Hurwitz observes, the sound of this first recording is a bit thin compared to some of the recordings to come just a very short time later. But what a wonderful recording to hear from the history of stereo. It bears all the key strengths of later recordings: terrific stereo imaging, good location specificity of instruments, excellent detail.

Anyone who enjoys Scheherazade should try Antar next, as this music is almost as inspired.

And HDTT honors the recording with a direct DSD256 transfer, tape warts and all. It is a copy of this recording as true to the tape as I may hope to ever hear. I am grateful to be able to listen to this recording in this pure state. Thank you, Bob Witrak.

Victoria Hall, Geneva. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Most of the albums listed above were recorded in the gorgeous hall in which the Suisse Romande recorded, Victoria Hall in Geneva. It was possibly the best recording venue of its day, possibly of all time. So many amazing sounding recordings were made there; I don't know of another venue with such a rich history of recordings except perhaps Waltham Town Hall and Kingsway Hall in London. There is a lovely richness to the sound, yet clarity and transparency are not sacrificed. The sound captured in that hall in these recordings is as wide, deep and three-dimensional as any. But what makes the sound of these recordings so special is the weight and power of the brass and the timbral accuracy of the instruments in every section.

Additional reading: I am consistently fascinated by the many excellent recordings from the early years of stereo, particularly the work from the Decca teams of that era. But, I'm a sound junky who loves to hear the a full orchestra being captured accurately in a three dimensional natural acoustic space. And that is what these early recordings made by the Decca recording engineers deliver. For those seeking more information about the evolution of the Decca Sound, I recommend:

Michael Gray's article, The Birth of Decca Stereo, from the ARSC Journal (1986), HERE, in which Kenneth Wilkinson is quoted as saying: "You set up the Tree just slightly in front of the orchestra. The two outriggers, again, one in front of the first violins, that's facing the whole orchestra, and one over the cellos. We used to have two mikes on the woodwind section—they were directional mikes, 56s in the early days. You'd see a mike on the tympani, just to give it that little bit of clarity, and one behind the horns. If we had a harp, we'd have a mike trained on the harp. Basically, we never used too many microphones. I think they're using too many these days."

Michael Gray's article, From the Golden Age, that appears in The Absolute Sound magazine, Vol. 11, No. 42, pp.103 – 110. (not available online)

An excellent article that is available online, The Decca Sound: Secrets Of The Engineers, contains far more detail and historical photographs, in which the author writes that Michael Gray had obtained access to the Decca archives beginning in 1984 when the editor of the Gramophone classical music magazine, Malcolm Walker, asked him if he would like to work with record collector and discographer Brian Rust, who was creating a Decca discography. Michael Gray is quoted as writing:

"As a result, Malcolm and I began to look at paperwork and there was a lot of it. On the producers' side—there was something called the Musical Record of Session, which was taken at the session itself with all the takes. Then there was the Log Sheet, which was a summary of all the information that went into tracking, or putting the sequence together for the LP record."

"Then I discovered there was something called the Electrical Record of Session, which was kept completely separate by the engineers, and these almost invariably included a date of session, or at least the first session, plus an indication of the microphones being used, their placement, the tape recorder and tape being used, and who was responsible at the session—that is to say, the initials of the engineer and tape operator."

"Well, those records were particularly fascinating to me and, as I was taking notes on the dates of sessions, I started to take notes on the microphone setups, which in the 1950s were very, very simple."