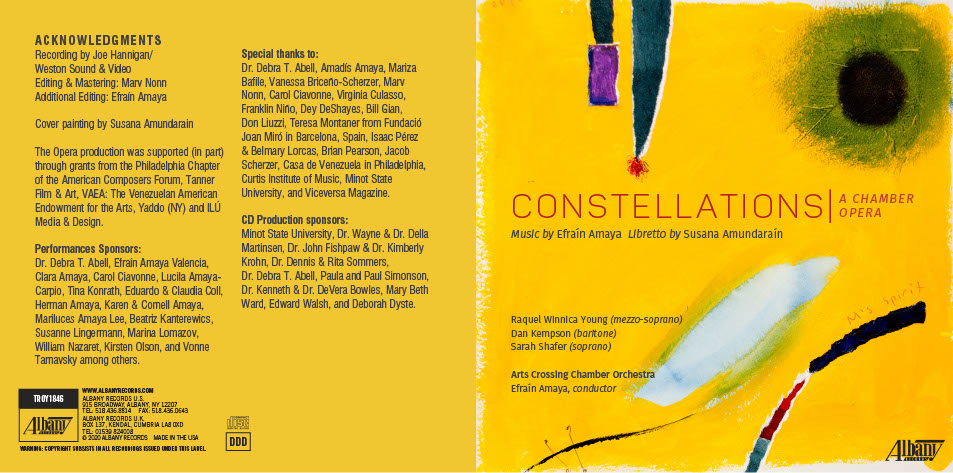

Sarah Shafer (s), Tessa; Raquel Winnica Young (ms), Pi; Dan Kempson (b). Arts Crossing Chamber Orchestra/Efraín Amaya. Albany TROY 1846. TT: 78.30

About a year ago—when it became apparent that the pandemic shutdowns would be dragging on for a while—the noted singer-actor Stephen Pasquale was interviewed by Classic Stage Company's Artistic Director, John Doyle (on Zoom, of course). On the subject of post-pandemic theatre, Mr. Pasquale hazarded that, when Broadway did return, we'd likely be seeing productions of more straight plays and small-cast shows, rather than a lot of panoramic blockbuster musicals.

The latest announcements suggest that Broadway won't be following that plan—counting instead on vaccines and proof thereof to keep large casts and audiences (relatively) safe—but opera could return, in smaller venues, via a similar route. The material is there, and I'm not just talking Mozart, Handel, and Pergolesi, though they're all fine. For decades, composers have been writing smaller, even chamber-scaled operas, partly to accommodate a stripped-down contemporary aesthetic, partly to encourage production by reducing the potential financial burden.

Efraín Amaya, a Venezuelan-born composer-conductor who currently teaches and conducts in Minot, North Dakota, couldn't have foreseen the pandemic when he wrote his "chamber opera" Constellations. But it's the sort of piece that would well suit a gradual return to the opera house, requiring just three singers (plus a non-speaking child actor) and a thirteen-piece orchestra.

Susana Amundaraín's libretto dramatizes a brief period in the life of Spanish artist Joan Miró ([ʒuˈam miˈɾo]—thank you, Wikipedia), when he was settled with his family in northern France, and had to be persuaded to escape to France and then Spain before the Nazis arrived. Besides the painter himself, the characters are his wife, Pi (Pilar), and the angel Tessa, reflecting Miró's interest in the subconscious and the metaphysical. Pi's disguising herself as a bird to communicate with her dreaming husband seems a nod to "magic realism," but she brings off the effect rather more mundanely, simply by making and wearing a bird costume.

I want to call Mr. Amaya's writing "eclectic," but that wouldn't be fair; rather, he has assimilated diverse influences into a cohesive, purposeful style. Working tonally, the composer has woven together intermittently dissonant, angular passages reminiscent of Menotti and curvaceous ostinato accompaniments harking back to Minimalism, to create liquid textures with crisp contours. The strong rhythms of Latin-American dances underpin several passages, while the distinctive, searching idiom of the thoughtful monologues is very much Mr. Amaya's own. His feeling for vocal writing is mostly natural, though the soprano's highest-lying lines militate against intelligibility.

Of the three soloists, Dan Kempson, as the artist, comes off best. His clear, forthright singing eschews the mannerisms that afflict so many baritones, and—save in a few uncertain moments at the start of Act II—his intonation is excellent. Sarah Shafer, as Tessa, offers a warm, compact soprano timbre, understandable except in the uppermost phrases, and a persona that, while sympathetic, maintains a discreet remove.

Raquel Winnica Young conveys Pi's concern, empathy, and resolve affectingly But she darkens her mezzo unnecessarily, rendering even her most important monologues incomprehensible without the libretto, and reducing her vocalism to a single, if attractive, color. Some of her English pronunciation is peculiar, with incorrect vowels and "r"s that become separate syllables, and, as the performance progresses, the top becomes noticeably strained.

The composer directs his thirteen-piece ensemble with authority. I'd have liked cleaner vertical coordination, though the sense of shape is unerring; in Pi's second vision of Tessa and in the final transition, I'd have liked a fuller sonority than these few players can manage.

The recording—apparently taken in performances, though the booklet doesn't tell us as much—is fine. Amundaraín's libretto has marked passages that are excerpted from other writings, but the booklet hasn't bothered to explain the identifying abbreviations. "JM," which tags Joan Miro’s own words (in English translation), is easy enough; "SJC" is St. John of the Cross and "STA" is St. Teresa of Ávila—Miró’s two favorite saints.

stevedisque.wordpress.com/blog