Trigger warning: This article claims that power cables can change the sound of an audio system.

To me, a review of AudioQuest power products is necessarily an article about their designer, Garth Powell. I wish everybody who is considering a Niagara power conditioner or Storm Series power cables (and more so people who think it's all a load of codswallop) could attend one of Garth's live presentations. Look out for them at your favorite audio show.

Garth's demos are almost performance art. His passion for the subject takes over his body as he runs from one side of the room to another to mimic current flow, hissing and bubbling with voice and hands to show induced noise, clapping suddenly and loudly (very loudly, with an accompanying "BAM!") to demonstrate a transient peak.

This is not theatrical misdirection, and when I caught the presentation at the Los Angeles Audio Show (LAAS) in 2017, Garth used a track from a rare album Marshland by George Marsh and Mel Graves to prove it. "Moonfire" features Aeolian wind chimes and double bass, a sparse, clear recording that lets you really hone in on the leading edges of those chimes, and of course the presence and texture of the bass.

It also highlights that important point about musical transients—that these 5 or 15 or 25 millisecond peaks are the real load on an amplifier. If you've ever watched the VU meters on an amp, you'd know the averaged output of most music, even playing loudly on less-than-sensitive loudspeakers, is low. "But if you scope it," says Garth, "there are very, very fast peaks even for a guitar or a grand piano. You don't need ear-splitting levels to be getting right to the edge of most power amplifiers."

At LAAS, Garth was demonstrating the flagship Niagara 7000 power conditioner on a $250,000 system, incidentally one that used the first production prototypes of the three-conductor Storm Series. The difference between pre- and post-Niagara 7000 is the difference between really good playback of that wind chime, and the sense that you could walk onto the soundstage, reach up and run your fingers through the instrument.

Even if you don't attend a presentation, Garth's voice is right there on all the packaging blurb and in the happily overwritten manuals, a chatty but firm style I now immediately recognize. The introduction in the Niagara 5000 user manual frankly sums up why we need one in the first place: "The mammoth increase in airborne and AC-line-transmitted radio signals, combined with overtaxed utility lines and the ever-increasing demands from high-definition audio/video components, has rendered our utilities' AC power an antiquated technology."

Levels of Power

Over several weeks, I tried various combinations of audio components and the following AudioQuest (AQ) power products:

- Niagara 1000 power conditioner, $999.95

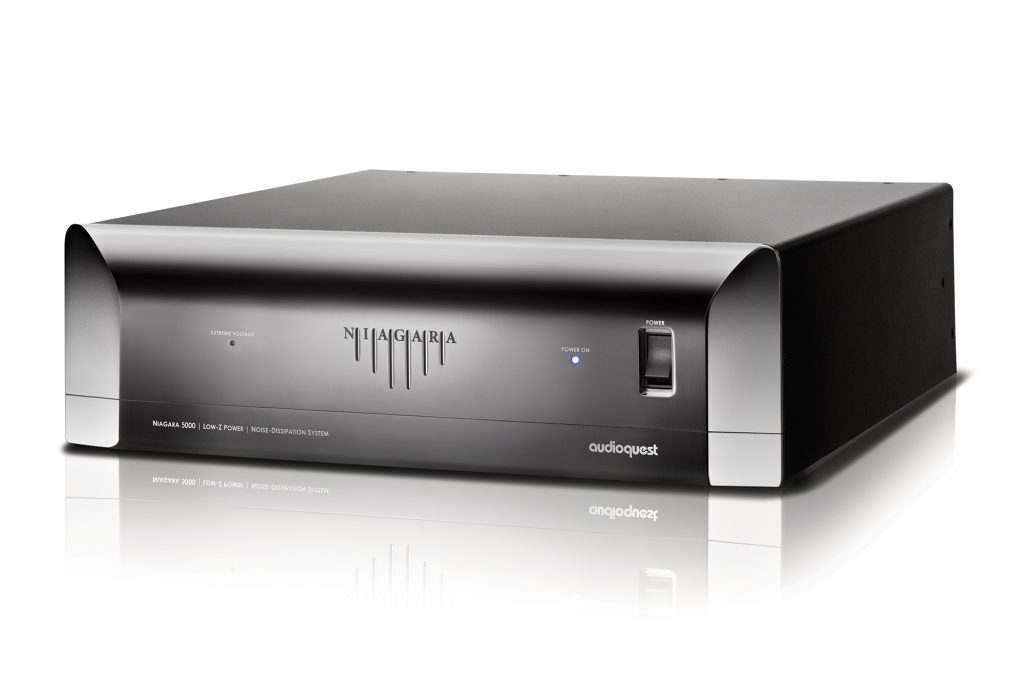

- Niagara 5000 power conditioner, $3999.95

- Thunder 15 A and 20 A power cables, 2m, $749.95 each

- Hurricane 15 A and 20 A power cable, 2m, $1999.95 each

Instead of "power conditioner" AudioQuest prefers to tag the Niagara series with two terms: "Low-Z Power" (Z is the sign for electrical impedance), and "Noise-Dissipation System". Garth approaches the cables as passive versions of the same system.

AudioQuest has a notoriously deep cable catalog, but here's a way to begin to make sense of it. For any given length, AQ cables can vary by conductor thickness, geometry, and metal type. The company uses only solid conductors, and going from cheapest to most expensive, we have long-grain copper (LGC), perfect-surface copper (PSC), a higher grade of perfect-surface copper (PSC+), and finally perfect-surface silver (PSS). Since many cables use multiple conductors, you can have different metal grades in the same cable, so as you go up the ladder, you might progress through some or all of these combinations: all-LGC to LGC / PSC to all-PSC, to PSC / PSC+ to all-PSC+ to PSC+ / PSS to all-PSS.

So, analyzing the Storm Series, the overall conductor gauge is 11 AWG. The entry-level Thunder cable is a mix of LGC and PSC. Next, and not featured in this article, is Tornado (PSC / PSC+), and then the Hurricane which is all-PSC+. Above Storm is the Dragon Series, which uses PSC+ / PSS and because of its cost (that's a lot of silver), AQ offers a thinner Dragon 16 AWG cable for source components. Both series feature the new filtered DBS, AQ's patented Dielectric Bias System.

Think of any combination of the AQ products I was sent, and the audio / video equipment I have at home, and I tried it. And guess what, I heard a difference. Every single time. Some were bigger, and some smaller. (There's a limit to how much a $700 wireless speaker system can be improved by a $2000 power cable.)

The general flavor profile involved the following ingredients: a drop in noise floor, better bass definition and extension, more detail, more air and space, a bigger, more precise soundstage, and a smoother sound and presentation. I couldn't perceive any change in coloration; it's the same white wine, just that instead of slopping it too warm or too cold into a cup, it's served perfectly chilled in the right wineglass. When you go back into the wall via stock cables, you realize that life before power conditioning was grainy and flat.

Corrupt Power Corrupts Absolutely

I started my experimentation with stock cables and the Niagara 1000, the baby of the power conditioner line. I was so amazed at what it did for the sound of a MOON by Simaudio 240i integrated amp, I had to ask Garth, "How is it so light, and yet so good?"

Garth has heard this question many times before. "People always assume it's empty and it's really not. It's loaded down with circuitry, but has a very thin aluminum chassis."

Garth half jokes that if he had to redesign it, he'd make it heavier just to satisfy audiophiles used to sound quality being directly proportional to tonnage. According to him, the Niagara 1000 contains 80 to 85% of the noise-dissipation circuitry in the 5000, at a quarter the price. Note, however, that there is only one high-current outlet, unlike the four in the 5000. So while the Niagara 5000 could handle a pair of monoblocks and a pair of subwoofers, the 1000 is better suited to smaller systems featuring, say, an integrated amp or a receiver.

After listening for a while with stock cables, I replaced the 15-amp power cord going into the Niagara 1000 with a Thunder. I expected only a marginal improvement—after all there was already active power conditioning on the circuit. It was such a jump that I actually cursed, because I now had to get my head around this new idea.

Garth hears that one a lot too. Even if you do use stock cords or somebody else's cords, he says, "I beg people to use an AudioQuest cord going into a Niagara because we're the only people—to the best of my knowledge—to have directional orientation for the noise-dissipation system. "

The patented system runs high-frequency noise back towards the wall to ground, and needs a cable with low resistance to those frequencies. The correct cable works with the noise-dissipation system rather than against it. "It's just like plumbing," says Garth.

A word, though, about that braided cable design of the Storm and Dragon Series. It has nothing to do with performance. An early prototype of this three-conductor design was enclosed in one sheath, which Garth described as "a spear". So the weave pattern is just to make the cable more flexible. It helps to remember, when you're struggling to get any of the Storm Series to make what should be an easy turn between wall and audio rack, that this is actually the usable version.

All Cables Matter

I remember when Naim Audio—one of my favorite brands—long a proponent of using just the basic cables that shipped with its systems, introduced an audiophile power cord. The Power-Line sold for what I thought then was an insane price for a power cable, $1000. In its suggested upgrades on the Naim website, the first option for many systems was not a better component, but the Power-Line. It puzzled and even disappointed me—I was among the many audiophiles who had judged without listening.

The experience of changing the stock cable on an amp to the AudioQuest Thunder is going to stay with me, because for the first time I clearly heard a huge, undeniable improvement from a power cable change alone. It was, in fact, so much like connecting the Niagara 1000 (using stock cable), that I recommend the $750 Thunder cable as a significant upgrade, especially if your audio system is built around a high-quality component that does more than one thing, such as an integrated amp with a DAC.

The higher grade Hurricane in place of the Thunder brings a little more of that ease that truly high-end gear has, so look at the Storm Series and figure out what would work best in your system, depending on both budget and system quality. Obviously, I'm not suggesting you buy a $2000 power cord for a $2400 amplifier, but if, like many of us, you're on a journey, you're not going to lose by buying the best cable you can. These products can stay through many, many rounds of upgrades.

My eventual "flagship" Niagara 1000 combination used a Hurricane cable from wall to power conditioner, and a Thunder cable from conditioner to the integrated amp and DAC, which was connected to Alta Audio Io loudspeakers, and fed by the S/PDIF output from a Sony Blu-ray player. When this system settled in and started playing, I actually texted a friend, and former employee of AudioQuest, asking why he'd left, because I wanted to call and yell at him. A fat, chromed power strip and two braided cables should not be able to make a basic system sound like it could retail at three times its cost. And yes, $3700 for just power accessories is the cost of a whole component, but this is performance far in excess of a component upgrade.

Proof by Subtraction

Eventually, I unpacked the full-chassis Niagara 5000, and moved over to my main system. I had a pair of class D power amplifiers on home trial, the PS Audio Stellar M700. So my first question to Garth was, "Would they need the power reserves of the 5000?"

"This is a common misconception among audiophiles," he said, and explained how a class D amplifier would actually benefit more from transient power correction than other topologies. A class A amplifier is running on full power all the time, so has the least dynamic power draw at the wall outlet when there are transients in the music signal. The highly efficient Class D, though, is running at a low idle for a steady signal, and when there are transients, it doesn't have a lot of reserve to draw from. Once on the Niagara 5000, those already dynamic M700s had their leading edges honed to nearly the sharpness you expect from live voices and instruments. And though these monoblocks are incredibly clean and detailed straight out of the wall, the noise-dissipation of the 5000 made them startle me every time I pressed "Play", as if Scotty with a super-fast transporter was beaming everything up (or down?) into the soundstage.

Garth prides himself on designing systems that remove noise linearly across all the octaves, ensuring that the product stays neutral and doesn't act like a dynamic graphic equalizer. With noise-dissipation, it's important to stress that most of the benefits are in the spaces between. It is not changing the perception of the fundamental, but uncovering all the harmonics and texture and detail that's 60, 70, 100 dB below the main signal. If your system is well set up, it's not so much that you hear details you never heard, but that those details take on a timbre and presence. Much of the improvement is in the "air frequencies" which is where you find so much of the magic of all this crazy gear we love.

Magic sure, but Garth stresses that he is an engineer, and all his claims can be measured. But how? It turns out to be elegantly simple: a difference file. Play a track on a digital system with stock power cables from the wall, and digitally record the output. Then add audiophile power cables or a power conditioner, and record the same track. On a computer, align the recordings perfectly so they start and stop at exactly the same point. Flip the phase on one track and add them together. What you get is a difference file—if the two files are identical, the result would be total silence. If the power cable or conditioner is making a difference (hopefully an improvement), the difference track should be playing all the information that was masked in the stock playback.

Garth sent me two difference tracks, one from a Niagara 7000 and one from Power Conditioner X, retailing at $5000. The tracks were created about a year ago at Bernie Grundman Mastering, and compared the Niagara 7000 to a number of competing conditioners. I expected to hear a collection of unidentifiable blips and clicks—random leading edges and low-level details. Instead, I heard music. It's metallic and thin sure, and there's little low frequency information, but you can identify the track; here, the opening bars of "Mediterranean Sundance / Rio Ancho " from Friday Night in San Francisco by Paco de Lucía, John McLaughlin, and Al Di Meola. You can hear the cheers and clapping, and clearly identify the guitars and follow the melody. I was startled, because that's a lot of information to lose. Power Conditioner X's difference file was a lot quieter and even went silent for a few moments, showing it was doing less work than the Niagara.

"But still," Garth allowed. "It's doing something. It's better than coming straight out of the wall."

Engineering Critical Thinking

Garth has been using this difference method for years—from his Furman days—to check all of his designs. He mentioned it when I asked him about the people who get upset when you talk about audiophile power cables, and insist its either placebo or outright rapaciousness turned retail.

When the critic is a non-engineer, Garth simply and peaceably says he can't do anything about previous situations where a person has tried something and it hasn't worked. Nor can he take responsibility for any other company's "fanciful marketing campaign with science that may or may not subscribe to basic stuff like Ohm's law". He has less patience for people he calls the "Double-E's" (electrical or electronic engineers) who get on the internet and talk about Garth's life's work being snake oil and hokum. And life's work it is—Garth is 56 and has been doing this since he was 15. "I want them to get off their- and you can quote me on this... I want them to get off their lazy rear ends and do some work. Because this stuff is so easy to measure, it's pitiful that they're not willing to do some work."

This is the same passion (though with the phase flipped!) that Garth showed at the LA Audio Show presentation. As an audio consumer, I'm happy he's so outspoken. One of the reasons I love being an audiophile is that I have preconceptions shattered all the time—my notions about power cables being the most recent. After I hear what I hear, it's important to know these products are designed by people who really care about what they're doing, and are not just "slinging big metal," as they say in the industry about people who sell a lot of high-end cable.

This is a good moment to mention what, for me, was the most interesting deployment of a power conditioner during my testing. I had my main system on the Niagara 5000 and it was sounding fantastic. On a whim, I connected my NAS, network switch, and router to the Niagara 1000, up in the cupboard where I keep them. (I told you I tried nearly any combination you can think of.) The sound eased up even more, with an even lower noise floor. Damn.

I wrote to Garth, asking him if he was surprised at this. He wrote back that network components will always benefit from RF noise filtering and dissipation, and that the Niagara 1000 is a great choice for those devices.

"Even though packets of zeros and ones will likely survive the data transmission intact, this issue is the Trojan Horse of induced RF noise that comes along for the ride," he said. Eventually that noise will hit an analog D/A circuit, and that's when the noise masking and other troubles begin.

And Finally...

In 2018, it's important to keep in mind the intersection of two technological developments—the proliferation of gigahertz frequency transmissions, from wi-fi routers to cell phones to Bluetooth devices, (with new items such as refrigerators, light bulbs, and door locks joining every day), and the use of low-noise, high-bandwidth, high-resolution digital audio systems. As Garth and any cable engineer will tell you, shielding against gigahertz frequencies is fiendishly difficult, and impossible to do completely. These tiny wavelengths are able to get in from everywhere and couple with musical signals, distorting them. Yet, both as consumers and industry, we are prone to looking at power cables and conditioners as if we're still 20 or even 30 years in the past, where this kind of induced noise wasn't as much of an issue.

After weeks of intensive listening with my selection of AQ products, I have one main conclusion. Paying attention to power cables and power conditioning is not obsessive tweakery for only the most committed audiophiles (you know, the ones who literally hear voices while alone in padded rooms). It is for anyone who pays attention to system choice and setup at any level—a fundamental and utterly essential part of getting good sound. Bring it on, triggered Double-E!

Niagara 1000 Low-Z Noise-Dissipation System

Retail: $999.95

Niagara 5000 Low-Z Noise-Dissipation System

Retail: $3999.95

Storm Series Thunder Power Cables, 15 A / 20 A, 2 m

Retail: $749.95

Storm Series Hurricane Power Cables, 15 A / 20 A, 2 m

Retail: $1999.95

AudioQuest

The author would like to thank Sunny Components (www.sunnyaudiovideo.com) for freely lending accessories and electronics to allow for a more comprehensive evaluation.