RADIO FREE CHIP

Ourselves in the tune as if in space,

Yet nothing changed, except the place

- Wallace Stevens

The guitar is a small orchestra. It is polyphonic.

Every string is a different color, a different voice.

- Andrés Segovia

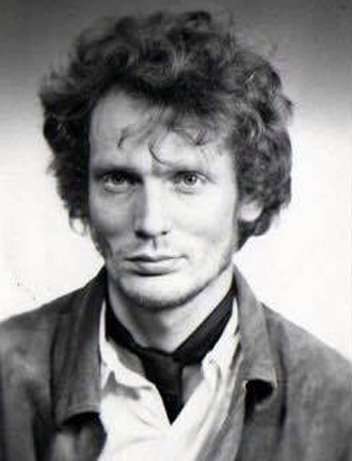

In January of 1987, Andrés Segovia embarked on what turned out to be his final tour of the United States, because on June 2 of that year, he passed away in Madrid, at the age of 94.

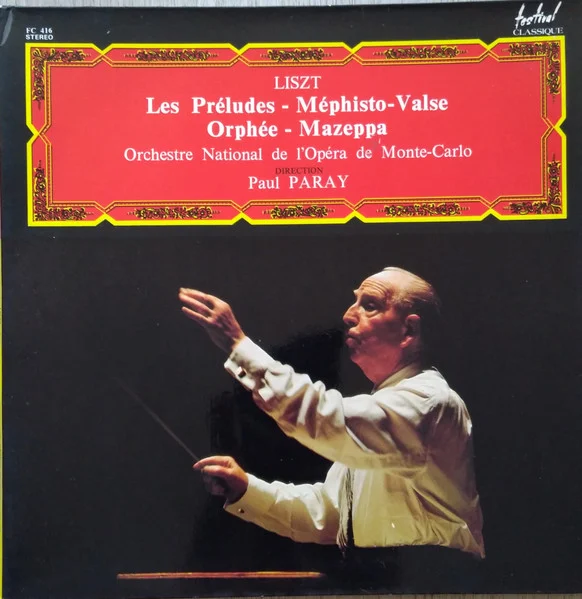

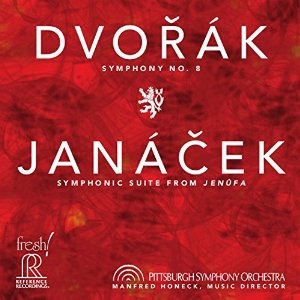

Born on February 21, 1893, in Linares, Spain, Andrés Segovia Torres championed the solo acoustic guitar as a concert instrument in the 20th Century. No, he was hardly the only instrumentalist to so elevate the instrument—the Catalonian Miguel Llobet and the legendary Paraguayan composer and performer Agustin Barrios Mangoré spring to mind—but he most certainly perfected and refined a commanding orchestral technique, inspiring many modern composers (and not necessarily just guitarists) to expand upon a performance repertoire which consisted in large part of music he'd personally transposed and transcribed from the baroque, classical and Romantic literature (most notably, for this enthusiast, from the J.S. Bach Home Companion, such as his legendary arrangement and performance of the challenging Chaconne from the Solo Partita for Violin in D Minor).

To many aficionados, Segovia's output from the 1950s marked his peak as a performer, and as a guitar tadpole, coming of age, I was particularly taken by two particular recordings—Segovia And The Guitar and Segovia On Stage—whose balance of acoustic intimacy and aural ambience simply transported me. There was something about the teardrops of his vibrato, the luminosity of his…tone.

I was lucky enough to hear him in performance twice, the first time back in 1972 with my mother on the campus of C.W. Post, a college on Long Island. I have a vivid recollection of the geeky suburban audience as they kind of shuffled to their seats in drips and drabs like a bunch of hobos, never you mind that he'd already taken the stage and was waiting for a moment of silence in which to focus.

And when said silence was not forthcoming, and the patrons kept drifting in, his face was contorted in disbelief, as if he were ready to blurt out, "Do you simpleminded motherfuckers know who I am?" Of course, being a scion of the late 19th century, he was too dignified for that, but he was not above a moment of pique, and suddenly this most elegant of performers violently strummed the open strings on his guitar with the back of his hand, making an appallingly gnarly sound.

I burst out laughing, as did a little boy sitting just in front of me, who proceeded to turn around and giddily eyeball the only other carbon-based lifeform who'd gotten the joke. And when even that didn't do the trick, Segovia stood up, calmly placed his guitar on a stand, and simply walked off stage—nor did he return until nary a soul could be heard shifting in their seats, rustling their programs or drawing oxygen.

Then he commenced to summon forth the most amazing performance. I particularly recall his orchestral reading of the familiar Sonata in A Major by Scarlatti (from Segovia On Stage), and I could not quite believe my ears. When I closed my eyes, I could plainly discern the moving bass and contrary motion of the top-most melody, as he simultaneously crafted a richly textured harmonic accompaniment; yet when my eyes were open all I could make out were boxcars of chords moving laterally up and down the neck of the guitar like a choochoo train. Whereas on a piano, the linear and vertical aspects of the music line up in a logical, sequential manner, on the guitar it seems more like a series of circles moving through adjacent quadrants, or so it appeared to this refugee from the Mel Bay Method, Volume 1…"Well," I remember thinking, "so, that's how he does it…okay…geez, what on Earth is he doing?"

Anyway, given the rocky start between Segovia and the audience, once he hit his stride, there was no stopping him, and the audience was so engaged, that as youngsters left their seats to sit in the aisles closer to the stage, he just couldn't stop playing—must've easily taken a dozen or more encores. Well, so inspired, when I was subsequently blown away by a performance of electric guitarist John McLaughlin's Mahavishnu Orchestra the following week, the week thereafter I quit school to buy a guitar.

The next and final time I heard Segovia in concert was at Carnegie Hall, in 1985 (in fact, this hectic eclectic actually attended the Segovia concert one night, and Wrestlemania One the next, thus encompassing the full range of human emotions from A-to-B). The house was packed, so much so, they even had listeners sitting behind the old man on the stage itself, like the peanut gallery on Howdy Doody (I half expected them to hold up signs like Olympic judges for performance and degree of difficulty).

Well, whereas in 1972, the old man was still at the peak of his game, some 13 years later he seemed extremely frail, and as he hobbled on stage with a cane, I held my breath. What followed was very emotional. Clearly he'd lost a yard or two off of his fastball, and while he wasn't playing any of the most demanding arrangements in his repertoire (such as the Bach Partitas), his guitar was messing with him big time, so much so, he had a devil of a time keeping in tune, and at one point his thing unraveled to such a degree, that this paragon of perfection actually hit a clam or two, stumbled, and had to stop, catch his breath and start over. Damn.

I felt like I'd been punched in the gut, and I began to cry; looking at the women adjacent to me, they too were tearing up. To see the old master humbled in such a way, given his Olympian stature, and the, for want of a better term…arrogance of his mastery, was very, very unsettling. Had he hung around too long? It put me in mind of watching the great outfielder Willie Mays stumble and fall chasing a foul ball, or boxers such as Sugar Ray Robinson or Muhammed Ali, well past their prime, their reflexes out of sync, hanging around for another payday, and having to avert one's gaze, as they got slapped around by ham and eggers.

Everyone was on pins and needles, after the intermission, as Segovia haltingly returned to the spotlight, and given the character of the man as an artist and a performer, you could readily discern how much he wanted to raise his game, and sure enough, he found his sea legs, and you could feel the crowd pulling for him after very piece—as he fed off of our love, and radiated it right back at us.

I was so moved by the humanity of the experience, of seeing Segovia so humbled, and of how he got up off the canvas and came back punching, that I went home and this recitative, THE BLUE GUITARIST, came pouring out of me.

I thought, some 32 years down the line, as I share one of the more poetic pieces of writing I ever crafted (upon the occasion of re-launching my blog, RADIO FREE CHIP, in a new platform), that it would be germane to share this backstory and much of the relevant music with you as well.

Do some artists and athletes hang on past their prime? No doubt. I experienced it with Segovia. I experienced it in an even more personal, intimate manner with Dizzy Gillespie and Papa Jo Jones. But can you blame them for wanting to die with their boots on, as the old saying goes? For every master musician such as Julian Bream or Gary Burton, who can discern the slippage, even if the audience cannot, and decide to call it quits, there are others for whom breaking up is hard to do. So cut them some slack, why don't you. A lifetime of give and take, the bonding between performer and audience—the creative act of channeling all that love, direct from the creator to you—is hard to put in the rear view mirror of life.

The blue guitarist swooned ever so slightly towards his constant companion, the beckoning shadow, half-remembered reminiscences of Linares, Granada, and past triumphs murmuring like a river of no regret. No regrets.

Yet again may we not indulge your attentions, your respect, as if we'd only just met, for I have so much to share. Fret not Andres, pluck slowly yet again, for the last dance has not come.

May it be as it was.

Dreamlike. This third leg moves me slowly. Poetry of the moment. They rise as if I were again young. Thank you for this state of grace.

Ah, if you could have seen me then—the arrogance of my mastery in full bloom—the gods themselves did blush. My heart, my vision—my only guides.

You will relent. I shall not.

For better and for worse I link my instrument to fate. You shall see. Stand by my side as we plot this brave old world. The guitar shall stand fast for no man made of mortal hands. Salon, so long, the stage of our destiny awaits my children.

Canción del Emperador. Mille Regretz. Emperors indeed, de Narváez.

Kings did bow. Ah, I was princely proud then.

Again? My quiver is empty. Fate mocks me, for I hear the music still, but my hands cannot follow. After eighty years I and this guitar are one; yet I feel so very far away.

Damn, these strings are not gut! This plastic age—I will not relent. Perhaps they did not notice. Improvise an arpeggio; it will not be so obvious. They are too kind. But I noticed.

Relent.

That andante of Haydn's—I can dance it yet. Echoes of harpsichords and massed bass viols. Courtly days past.

Relent.

These strings shall obey me. Be in the moment, not in the past. They cannot return with you. A rest.

Berceuse d'Orient. Oh, Tansman my friend, it is returning to me. Hear how the silence haunts our every phrase; the dark ardor of the moving voices, the muted rays of heaven, the low moan of those still on Earth.

Ah, the preludes of Villa-Lobos. I shall not relent. That woman, caught up in the moment, an insight lighting her eye.

Not yet...not yet. One more dance, a final bow.

How this music moves me, comes through me, in red wines and Moorish minarets, Parisian applause and Andalusian sunsets.

A pause. My own little orchestra, the spirit eternal, a ringing. For thee.

Be.

Ring vibrato, ring, ring right through the center of it all like some stately French horn.

Fall.

Make them take notice, for my time is past.

All my children. They shall carry forth this vision for a thousand years. All not in vain.

Dance Granados, dance once more. Let us take them on a journey that if they may not follow, at least they shall know.

I remember it all now, those curves—I could not take my eyes off of you. Weren't we the grand pair then? Again. I can make no fast moves, but no tempo shall intimidate me, not when they indulge me so with their love.

Caught up in the moment, shoulders stooped in a final embrace, the blue guitarist forgot his future, forgot even his past, falling, falling into her amour once more.

No pain, no regret. He was kingly yet.

You shall not see my like again. A thousand beginnings commence with one such moment, one final farewell.

Peaceful, composed amidst the turbulence and bluster around him, the blue guitarist took a final bow.

Grand. Graceful. Courageous. Commanding. Nobility.

Segovia.