Confession is Good for the Soul

Those few pilgrims who've remained in touch, and kept up to date with RADIO FREE CHIP's infrequent musings, might just recollect how a persistent and recurring theme of recent columns centered around how contented I was with my rig, how my system had evolved to the point where I could not envision myself being any happier…least ways, not to the point of reinvesting in new and improved versions of even better gear, least ways, not to the point where I found myself lip synching choruses of "I HAVE TO HAVE IT."

Barely had such thoughts cleared the conning tower, escaped the Earth's gravitational pull, and settled into a long journey in the general direction of interstellar space—just a hop skip and a jump behind Voyager 1 and Voyager 2—when my internal radio telescope began picking up faint signals against the persistent background noise of the Big Bang.

Earthling…

You…Are…Full…Of …Shit…

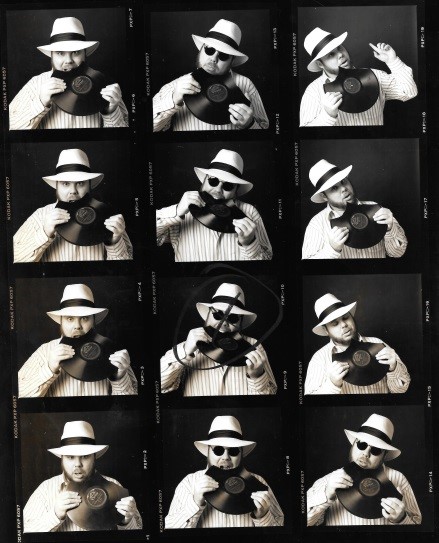

The lack of scientific decorum as transmitted by alien life forms notwithstanding, one could make the case that Chip's heart was willing and his flesh was weak, because no sooner did I speak, then sim-sol-a-bim, look what just arrived in my reference system.

Are these than my last territorial demands in high end audio? Possibly. Still, as I make my way into the wilderness in a quest for spiritual redemption and thus to bypass all temptation, David William Robinson often appears on Skype in the form of a Desert Jinn, whispering sweet nothings into my ear about Ethernet cables, Amazon Fire & Amazon Prime, 4K audio/video, and sophisticated mods deploying all manner of sepulchered triode artifacts, and I feel myself weakening.

Forgive me Lord, for I know exactly what I do.

Le Guerre est Finie...

When compact discs and playback systems first began appearing in the early 1980s, those who'd cut their teeth on the hi-fi breakthroughs of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s had decidedly mixed emotions. Yes, lack of skips and pops and scratches was cool for sure; so too was signal to noise ratio, frequency extension, transient impact and lack of compression, let alone the potential for something approaching the true dynamic range of live music.

Of course, while the Lord giveth the Lord also taketh away. And in short order, many amongst our ancient order of holy men, hunkered down defiantly with our turntables and LPs, telling anyone who would listen (assuming that anyone actually did listen) that something was surely amiss. Some mastering engineers, liberated from their temporal obligations to the RIAA curve, went bat shit, and began hot rodding new releases to the point where legal action for cruel and unusual punishment was called for: boomy bass and sibilant, screeching highs were the order of the day; and often, while the final products were very impactful, what does it profit an audiophile to gain a world of more impactful transients and greater apparent volume, yet to lose the soul of the music—those ambient cues which conveyed a sense of space and venue, not to mention how fatiguing it was to listen for even short stretches.

Additionally, when in the process of a direct A/B comparisons between digital remasters and the original analog sources, some among the throng suggested that there was something rather surreal about the digital variant. Or put less elegantly, "That is not how a real piano sounds" (or words to that effect). And in those productions where the acronym DDD appeared, some of us viewed this less as a promise than as a threat.

Not to belabor this point, but how many of you had cause to purchase the original all digital recording/mastering of Glenn Gould's Goldberg Variations? May we have a show of hands, please? Okay, and how many of you subsequently purchased the 3-CD reprise of Gould's A Sate of Wonder, his complete Goldberg Variations, sourced both from the pianist's famous 1955 recording, and his penultimate 1981 visitation in the twilight of his life, assembled from newly discovered analog back-up tapes, forgotten in the rush to get the original all-digital masters out and about. Once the AAD release trumped the DDD release, the DDD release slinked ignobly back into the shadows, so much more musical and human did the newer, less zippy version prove to the naked ear.

Having said all that, the art of digital recording, digital mastering, digital remastering, digital processing, digital streaming and all things digital, has come a long Goddamn way, some 35 years down the line.

A fact apparently lost on some Vestal Virgins who fancy themselves authentic audiophiles and keepers of the flame, and I cast that first stone as someone who has a nice analog front end, and over 7000 LPs in his grimy man cave.

Additionally, when this self-same Chip Stern produced drummer Ginger Baker's trio session for Atlantic records (Going Back Home) featuring Charlie Haden and Bill Frisell—Ginger's first recording as a leader to reference those original jazz inspirations which made him want to be a musician in the first place—Chip did so in the analog domain on a vintage Studer A80, running ½" tape at 15ips with no Dolby.

However, we also ran 24-tracks of ADAT as a digital back-up, which came in quite handy when we had a drop out on one tune, had to do a punch-in on another (where Ginger's bass drum pedal came loose mid-solo compelling us to do an edit and record a new ending), and finally on Ginger's ambitious arrangement for "East Timor" where we took advantage of the ADAT's multi-tracking options.

Still, having doubled down on my analog pedigree, I cannot tell you how utterly pissed off I was upon showing up at a dog and pony show in Brooklyn, staged by a Kings County high-end audio dealer to specifically showcase a friend's state of the art floor-standing loudspeakers, having spent several hours carefully assembling a CD demo disc, only to discover that this nosebleed did not have a digital playback medium in his reference system. I cannot tell you how much I wanted to excoriate this pretentious little dweeb, but for once, I kept my big mouth zippered.

Again, we are not in any way suggesting that the LP experience takes a back seat to the digital experience. Recently I had the opportunity to A/B a very nice digital mastering of Michael Jackson's Off the Wall, with a stock commercial LP I've had in my stash since the record was first released, and, in the interest of full disclosure…game…set…VINYL.

But again, it bears repeating, schmuck…render on to Caesar that which is Caesar's because, without putting too fine a point on it, LE GUERRE EST FINIE.

Chip's Digital Compilation Disc: Dog Yummies, Volume 1.

- Sonny Rollins - Way Out West

- Ahmad Jamal - Saturday Morning

- Ralph Toner & Gary Peacock - Beppo

- Bill Frisell, Ron Carter & Paul Motian - Pretty Polly

- Jon Iverson - Metalanguage

- Jonathan Faralli - Cartridge Music [by John Cage]

- Stevie Ray Vaughan - Tin Pan Alley

- David Bowie - I Can't Give Everything Away

- Georg Solti - Richard Wagner's Das Rhinegold [Scene 4; Schwules Gedunst]

- Georg Solti - Richard Wagner's Das Rhinegold [Scene 4; Abendich strahlt]

- Georg Solti - Richard Wagner's Das Rhinegold [Scene 4; Rhinegold Reines Gold]

- Rene Marie - Dixie/Strange Fruit

- La Rondinella - A'her Noghenim

The Post Modern Model-T of the Digital Epoch

Over the past 10-15 years, as professional music scribe and a consumer in my own right, I've had the opportunity to own and audition a number of digital front end components for varying lengths of time sourced from the likes of Magnavox, Marantz, California Audio Labs, Denon, Toshiba, Sony, McCormack, Njoe Thoeb, Linn, and Luxman. And again, to reiterate for the benefit of the LPs-or-nothing crowd, with the passage of time, my perception of the digital experience is that thanks to the interplay between end users and designers, the format has gotten progressively better and better, to the point where I found myself less focused on the digital experience per se, and more engaged by a progressively more natural, engaging sense of the musical presentation.

Having said that, in adjudging the natural balance between price and performance, it is hard to comprehend how comprehensively OPPO Digital has redefined our expectations of what constitutes a true state of the art digital experience, and what we may reasonably expect to pay for it.

Whether in my own system or in those of friends, be it an extended hang or a short kiss and tell, my experiences of OPPO universal disc players, and their continuing evolution from the BDP-83, through the BDP-95 and BDP-105, to the new UDP-205, has been a revelation.

I ponied up to purchase a new UDP-205 at the behest of PF Editor David Robinson, who believed both that it represented a profound evolution in performance and value over as good a performer as the BDP-105—and that it would prove to be a significant game changer in my system. Not to mention all of the new technology it accommodates, thus allowing me to spend more money on….oh, never mind.

Not that I ever doubted Brother Robinson, but even given my ongoing experience of the OPPO Digital sound signature, I was startled by how definitively how they had advanced the state of the digital art (based in large part on technological advances of OPPO's own devising). The OPPO UDP-205 sets a daunting new standard for digital front end components, at a remarkable price point of $1299 (only $100 more than the BDP-105 sold for). The price/performance balance proves even more compelling, when compared both to CD players and multi-format disc units costing significantly more.

Often compared to a Swiss Army Knife, verily, the new UDP-205 is a post-modern Model T of the evolving digital epoch.

Having made that bold claim, if I might indulge yet another parenthetical tangent, before returning to this narrative thread, one of the reasons I heaped so much contempt upon that nose-bleed Brooklyn audio dealer with his pretentious anti-digital predilections earlier in this review, was because the nature of technology is such, that as years go by, the cost-value benefit accruing to the consumer have advanced to an astonishing degree over the past 35 years, and even more so in the past decade. I am not just referencing digital front end components, vis-à-vis musical playback, but the astonishing evolution of modern monitor technology, both in the Home Entertainment realm, and the world of computer technology.

As I have no doubt referenced in previous Positive Feedback musings, I can recall with some degree of bliss how utterly captivated I was by the initial roll-out of a 42" Plasma Monitor at one of Stereophile's High End Audio fandangos in [Los Angeles, circa 1998?]. I do not recall the precise brand, but I vividly recollect how they were playing a very simple shot of a bucolic nature scene, from the perspective of someone looking out a window upon a verdant hillside in the late afternoon California light. It felt as if I was looking out the actual window myself in real time. When I asked the company rep what this 42" Plasma monitor retailed for, he immediately dashed my hopes by saying $11,000, adding helpfully that in the previous year well-heeled first adopters were ponying up $14,000. Well now, that was encouraging. "I guess I'll get around to buying one in fifteen years," which turned out to be true, as my Panasonic 42" Plasma ended up costing me like $699 in the post-Christmas sell-thon of 2012-2013.

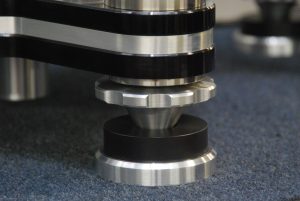

It is worth mentioning that part of the Desert Jinn's enticements vis a vis stepping up to an OPPO UDP-205 4K Ultra Audiophile Blu-Ray Disc Player, was not only that it was equipped with two advanced new ESS Technology ES9038PRO 32-bit HyperStream DACs for both stereo and 7.1 channel analog audio, but that it was capable of capable of playing both the new 4K UHD Blu-ray discs as well as 4K media files, and thus offered me the option of stepping up to the advanced new 4K TV Monitors, whose price in the marketplace had likewise come way, way down…SIGH…which brings us, dear readers, by a commodious vicus of recirculation, back to our tenuous narrative thread and audio environs.

Right out of the box, ice cold, and without any burn-in whatsoever, I was taken aback by how much better the UDP-205 looked and sounded than previous generations of OPPO Blu-Ray Universal Players. Straight away, in the audio domain, I was conscious that there was far more harmonic detail; significantly better timing; greater depth of field and a decidedly more analog sense of ease to the presentation.

Six hours later, having left the UDP-205 on in repeat mode, I returned to my listening chair to discover that the depiction of the soundstage, the overall sense of an acoustic venue, had deepened considerably. There was, at the risk of repeating myself [but when has that ever stopped me], simply a lot more there THERE. I could feel the soundstage starting to center and settle in as the midrange began to flesh itself out, images becoming more defined and palpable in and of themselves in a capaciously expansive, quiet black background—coming vividly to life with a distinctly [there's that metaphor again] analog aura in a palpably expansive acoustic space.

Over the next 50-100 hours, to advance the burn-in process, as I allowed my Blu-Ray of Lawrence of Arabia to cycle and cycle and cycle in a continuous loop, I became aware of how the folks at OPPO, not content to rest on their laurels, had not only achieved remarkable new levels of resolution, but that a wealth of heretofore shadowed digital information had blossomed in the light of day, owing no doubt to an advanced pair of ES9038PRO 32-bit HyperStream DACs deployed on the UDP-205—and, Chip would suggest, a much beefier, ultra-quiet new toroidal power supply. OPPO itself claims that their new toroidal power supply "provides superior power efficiency, virtually no magnetic field interference, and a very robust and clean power source to critical audio components." Again, I experienced this in the form of significantly enhanced signal-to-noise ratio, better timing, and a greater sense of…liquidity and ease.

Likewise, what OPPO describes a "true differential signal path from the DAC to the balanced output," allowed me to maximize gain, minimize noise and enhance detail and resolution by running things fully balanced from the stereo output of my UDP-205, to the balanced input of my tubed Rogue Hera II preamp (with a set of Acoustic Zen Absolute Copper Balanced Interconnects), and from there, still fully balanced to my Rogue M-180 monoblocks (outfitted with the splendid sounding KT-120 output tubes).

And so, having put well in excess of 100 hours on my OPPO UDP-205, confident that I have arrived at some fully fleshed sense of is presentation and performance, I feel confident to offer some conclusive observations.

Frequency wise, the highs smoothed out and revealed a wealth of upper partials and harmonic detail without any hint of hot-rodded brightness, fatiguing glare or sibilant treble artifacts, or as Sun Ra was wont to chant, Space is the Place, and was there ever a lot of it—a smooth operator, to be sure.

In auditioning the agelessly innovative pianist Ahmad Jamal's "Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child" (from his most recent release, Marseille), I was struck by how silky smooth and natural the depth and breadth of the midrange proved, contributing to the kind of capacious soundstaging cues I crave, all the more engaging given the UDP-205's image specificity and palpably enhanced sense of space—projecting a more believable aura of an acoustic venue than I ever experienced with either the 95 or 105, with which I never lodged any audible complaints—I must say, that it is genuinely truly impressive to experience something already so satisfying, getting significantly better. All the more so, on this same Jamal track, given the UDP-205's ability to convey what I can only describe as a lifelike, triangular, three dimensional depiction of Jamal's piano, James Camrack's bass and Herlin Riley's drums on the soundstage (and seeing as how I was moving back and forth between my audio sweet spot, and my drum kit in the adjacent room, when I got back to my listening chair and heard how precisely the UDP-205 conveyed the shape, sound and physical presence of Riley's ride cymbal in an acoustic space, without in any way sounding etched or analytical, it took my breath away).

However, did I neglect to mention that this trio is augmented by a percussionist who functions as something of a textural wild card? Manolo Badrena is a special talent, who has a genuine gift for echoing and italicizing the character of each instrument in the band, sometimes with firmly articulated tuned skins, other times with barely perceptible little colorations—bell-like metallic sounds, airy whistles, serpentine rattles—skittering across the soundstage a like flotilla of purposeful fireflies. Again, to hear these little sounds so firmly yet delicately depicted by the UDP-205, often intermingled with street sounds five floors down on 181st Street, made the skin tingle, and conveyed that sense of a live acoustic that all devout audiophiles cherish…and inspire them to reach for their credit cards, God Willing.

Then there was the balanced, focus and taut, chewy immediacy of the bass I was able to achieve on some uniquely challenging recordings, to particular effect in fleshing out the elusive presence of Steve Swallow's acoustic electric bass guitar with John Scofield on "Wildwood Flower" (from the guitarist's album County for Old Men), and Billy Cox's leviathan Fender Jazz Bass vamps from Jimi Hendrix's Band of Gypsies on "Who Knows."

Again, by way of an explanation, allow me to backtrack. I have never deployed loudspeakers with Leviathan woofers (presently, three-way Meadowlark Ospreys, with a 7" Scan Speak woofer, 5" Vifa Midrange and 1" Scan Speak Tweeter), my priorities are to achieve spacious, holographic soundstaging with tight, tuneful bass in my main reference rig. Which is not to suggest that my system is wanting in low frequency snap and slam (not when powered by my winter amps, the Rogue Audio M-180 monoblocks, putting out roughly 150-watts per side into 8 ohms in UltraLinear, while my winter amp, the hybrid Rogue Medusa, is slam personified, putting out 200 watts per side into 8 ohms, with a damping factor or 1000).

The reason I referenced these two tracks was to ascertain how the UDP-205 might flesh out and focus the bass, because these recordings are curiously challenging in their own way.

Swallow's Citron AE5 Signature Model (an acoustic-electric 5-string bass crafted by the renowned Luthier Harvie Citron, and fitted with a high C string, whereas most modern players opt for an extra low B) does not jump out at you in terms of our accustomed sense of transient snap, and the leading edge thereof. Swallow famously plays with a pick, uses mostly upstrokes, and favors a very warm sound that suggests the low end moan and spread of the organ pedals on a Hammond B-3, more so than the bite and attack of a solid body Fender. On this performance of "Wildwood Flower" his sound remains in the basement of the mix, never leaping, propelling the swinging 4/4 groove as adjunct to the drums, a harmonic reference point for the guitar. The UDP-205 in no way italicized Swallow's sound, nor did it flesh it out in the coarser sense of that term; no, the OPPO illuminated its image, delineating the outlines of this ultra-low end instrument so that it was neither flabby nor indistinct, fleshing out its sing-song characteristics, while depicting the acoustic space between guitar, organ and drums, so you could literally point to it, and go, thar' she blows. That is to say, you could always see Swallow's bass, even if given the cloak of invisibility this most supportive of players proudly portrays, you couldn't always hear it, if that makes any fucking sense.

Likewise, Bill Cox's Fender Jazz Bass with a Band of Gypsies. Clearly, given the solid-body nature of his instrument, and the wall of Marshalls Billy was plugged in to, not to mention the visceral nature of Hendrix's sound and the sheer volume, Cox's bass guitar is clearly a horse of a different fire department. And whereas Noel Redding, who played with a pick, tended to shadow Jimi's chords and melodies, Cox operated more as an adjunct of the drums, Buddy Miles being a more centered, less discursive presence than Mitch Mitchell. Still, while hardly indistinct, in all the years I've been listening to "Who Knows" and "Machine Gun" and all of the iconic performances from New Year's Eve at the Fillmore East, half a lifetime ago, I always found Cox's bass guitar, given his reliance on a more traditional form of low end equalization, to be tonally a tad lugubrious, though rhythmically chiseled in stone. Again, the OPPO UDP-205 does not substantially fatten or spotlight the bass, so much as clearly frame it through a deft depiction of the acoustic space. That is to say, the UDP-205 illuminates the silences themselves, elusive as they might be, in this cauldron of sound, while sustaining the physical impact that rock listeners relish in a live performance; it lends a degree of subtlety, a touch of refinement, to an experience, that when taken at something like concert hall volume levels, sustains the physical impact of a seat in the audience, while exerting the kind of welcome control generally only experienced by the sound engineer at the board, tweaking the house mix, or the musicians on stage (monitors and God willing).

Color me impressed.

However, in bringing my aural ruminations to a close, I must say that the most telling and engaging aspect of the OPPO UDP-205's presentation for me, was shortly after the burn in process began, how much more profoundly holographic and dimensional the entire presentation became.

That is to say, my sense of a point/source was practically obliterated.

Less a sense of bearing witness to an event, than BEING IN THE EVENT.

This idealized yet accurate portrayal of an aural painting was particularly vivid when listening to the spooky intimacy of guitarist Jakob Bro's trio performance of "Shell Pink" from his ECM recording Streams. On this particular track, drummer Joey Barron, a master of touch and tuning, draws the listener in with his supple brush work, and a small yet uncommonly resonant bass drum sound (the resounding presence and low end oomph a product of how loosely Baron tensions the bass drum heads, giving each delicious baby boom the caramel allure of calf skins). Then add the magisterial sepia grandeur of Thomas Morgan's upright acoustic bass, beautifully buttressed by the OPPO's supple control of bass dynamics; it's accurate rendering of complex bass tonalities—just add Bro's sublimely ambient, ruminative electric guitar, and it makes its own gravy, for an aural dog yummy of Alpine grandeur.

What else can I say, save to gild the lily?

So it handled the make believe ballroom acoustic impressionism of a modern recording studio on the modern digital Monet paintings ECM is so adept at depicting, but how about the great analog recordings of yore, which old codgers such as myself love to partake of through the SACD and Blu-Ray mediums?

Again, the UDP-205 got out of the way and allowed the music to breathe without adding any sense of what for a better terms I would characterize as digital etching—that is to say, too damn real, sort of out of scale with the original acoustic event, if that makes any sense. I have always been an enormous enthusiast for the acoustics of Chicago's Symphony Hall as captured on those classic RCA Red Seal with conductor Fritz Reiner in the wheelhouse, while producer Richaed Mohr and engineer batten down the hatches.

The UDP-205 excels at being able to sort out and backlight individual images while maintaining the essential balance of the acoustic event, and in the SACD mastering Reiner and Van Cliburn's 1961 recording of Beethoven's Piano Concerto #5 (the Emperor), there is no hint of digital caffeine jacking up the performance, for those who are hard of hearing. The analog/acoustic event, the warmth balance of the hall, the perspective of an orchestra seat, and the elemental stereo expanse of the orchestral soundstage (presumably rendered in a classic three microphone configuration), represents in my mind the apex of the analog concert hall sound. Not only does the OPPO handle all of the big sweeping gestures, but I vividly recall one passage in the first movement, where the UDP-205 did not sweat the smaller details of Van Cliburn's upper register fantasias, before rising to the dynamic demands of the soloist and orchestra when the pianist brought down Ludwig's hammer, and the orchestra responded in kind.

Take that experience, and magnify it by ten on the remarkable 24/48 Blu-Ray box set of Georg Solti's historic Wagner Ring Cycle, of which I am only a recent convert, having never had access to the 21-LP box set with which to primp and strut before less well-endowed audiophiles. Sniff. And when I say Box Set, you'll forgive me for suggesting that there are a host of CDs (the 16/44 Box comprises four complete operas on 2-4-4-4 discs respectively) encamped in this black and gold sarcophagus. There is in fact, only ONE DISC, and it contains more than 15 hours of music. I am a big fan of the Blu-Ray format for audio as well as video purposes, and for gear audition purposes, I often turn to the conclusive three scenes from Das Rhinegold, recorded in 1958, when the Gods ascend to Valhalla, the apotheosis of the emerging stereo format, and some of most majestic music I have ever heard. Whereas the Reiner/Van Cliburn Living Stereo SACD is the apotheosis of a concert hall experience, simply and directly rendered and conveyed. Solti and his fanatical Decca producers and engineers, deployed the acoustical grandeur of Sofien Hall in Vienna, Austria, a multiplicity of meticulously positioned microphone feeds, elaborate editing stratagems and state of the art 1958-1965 stereo technology to present a Unified Field Theory depiction of Wagner's complex universe in what is widely considered to be one of the greatest recordings ever made, if not THE GREATEST. And for good reason, correlating as it does a swelter of complex orchestral, vocal and choral group gropes, while maintaining an acoustically synergistic unity over the course of four widely separated, marathon recording sessions, years apart. The OPPO helped me to discern why so many people I respect hold to the opinion as to Solti's Ring Cycle's place of honor in the Alpine peaks of the audio experience.

The OPPO's handling of the enhanced dynamic range and resolution inherent in the Blu-Ray format is likewise both as elegant and natural as my SACD experiences, save that the immensity of the soundstage and the illumination and image specificity of all those voices amidst such a capacious orchestral pallet, is just so big, yet in scale, that it steals my breath away. That immense soundstage, capturing as it does the massive sweep of each and every section of a gigantic orchestra, is rendered with an expansive grandeur, a tonal detail and dynamic complexity that would put the feet to the fire of any digital delivery system. And yet once again, the OPPO handled both the biggest and smallest passages, the most demanding transients, with a sense of ease, and touch of the poetic. I mean that big crack of an anvil/hammer, and the timpani explosion which it sets off, in a system which tracks such passages with less control than the UDP-205 exerts over such big gestures, would simply break up like a dried cracker (that dreaded, oh my God, to I have a blown tweeter sound).

Speaking of blown tweeters, I have blown yet another deadline, given my obsessive tendencies, and so I hope you'll forgive me if I hop, skip and jump over significant advances which the UDP-205 offers in the way of its improved new headphone circuit and in the area of video performance, which in many ways, might be even more dramatic and readily discernible that the audio refinements. I promise I will return to both when I've had a chance to do a more in-depth analysis somewhere down the line on the coming year.

In part because I am only like 15 years late in submitting a review of the remarkable Grado PS1000e headphones. "Not 15 years, Chip. Tut Tut." Really? Are you sure? "Absolutely not, but you have been obsessing for an unconscionably long time while you burned them in, schmuck." However, I may no comfort myself with the knowledge that the headphone circuit of the OPPO UDP-205 is such an upgrade over that of BDP-95 and BDP-105, that I have a much truer, more accurate and refined source to readily report on the Grado's reference quality attributes, knowing that I can now bet the ranch on what I am listening to. Because at the default volume of 75, straightaway, the sound is really fucking good; the gain structure is much more subtle and refined than that of the BDP-105: Less apparent volume yielding more resolution, if that makes any sense—a really balanced sound from top to bottom.

As for the video, well, I was straining in my heart of heart to define what I divine to be the greater resolution, truer colors, more supple balance and more discernible detail the OPPO has to offer…again, a significant uptick over the BDP-105, itself no sloucher. But then, my audio buddy, the gifted photographer Arnaldo Vargas (and his faithful dog, Pele) came to the rescue. I put on my Blu-Ray disc of the restoration of Lawrence of Arabia, one of my favorite movies, with its extraordinary desert vistas, and complex contrasts of space and light. I was trying to explicate how much more…contrast there seemed to be, how my sense of say, the light of dusk in the desert was so much more…amber…so much more…vivid…more fleshed out.

Well, Arnaldo, who as a photographer, deals in issues of contrast and light the way some of us might breathe, understood instinctively what I was trying to convey, and cut immediately to the chase: "There's something special about the resolution of the new OPPO. It visually showcases the full dynamic range of the blacks. That explains why you feel like you're able to see so much deeper into details that were previously hiding in the shadows. I mean, that's what the OPPO is doing so well, so your sense of lights and colors, foreground and background is so much more vivid. When people talk about a screen having a 1:10,000 contrast ratio, that's all well and good, but the weak link in taking advantage of that spec is usually not the TV or the media, but the playback device itself."

And there you have it. Would be nice for sure to have access to some state of the art gear to cross-reference against the UDP-205, given all of the flowery experiences I have enjoyed in breaking it in, you know, some pricey stuff, because audiophiles tend to distrust gear that is too reasonably priced, or as one self-inflated douche nozzle once dismissed me: "Chip Stern? He has no credibility—he uses $4000 monoblocks." Ah, yes, what they used to characterize in the old Nucoa Margarine commercials as "the higher priced spread." Oh, ag-oh-knee.

Be that as it may, I was worried I wouldn't have enough to say about the OPPO and the audition process, and as per usual I have already exceeded 5000 words, so let's just leave it at this. I have been referencing and cross-referencing gear, in search of audio nirvana, all my life, and as a certified, professional high end audio scribe for the past twenty years, so I have muscle memory of a lot of gear, in a lot of systems, in a lot of combinations.

And basically, for as long as I can remember, the weak link in my audio signal chain was invariably my digital front end, both because as we've already discussed, the growth curve of the format over the past 35 years has been a series of baby steps, because the higher priced spread in terms of the technology's cutting edge, was invariably well out of reach, financially.

Again, there have been period as a professional scribe where I've enjoyed extended conjugal visits with the high priced spreads, and so, I could readily understand how high the bar had been set, and what I was missing—if only me and those cash challenged pilgrims who follow my audio ruminations were more well-heeled…alas.

Well, my muscle memory of the higher-priced spread is such that in my own system I have come to comprehend what sets apart chicken-salad from chicken-shit, so to speak. Which is not to say that's I've been suffering, because in audio, out of sight is often out of mind; if you can't be with the one you love, love the one you're with—everything is relative, and a good system is often more than the sum of its parts. Just throwing money around does not guarantee that you will achieve system synergy, and that things will ideal couple with your own personal acoustic space. I have always been impressed by music lovers who get more out of less, and make their compromises work for them.

So I feel safe in saying, with some sense of spiritual certitude, that the OPPO UDP-205 represents no-compromise audio-video performance at something resembling a real world price, where you won't have to dread remembering the words of the old fairytale, "…and Rumpelstiltskin was his name."

If you have high end audio aspirations, but department store budget—and in the real world, the OPPO's price of $1299 is a considerable sum of money for many mere mortals—then take heart. Because the UDP-205 plays all of the modern formats, and is oven ready for the emerging 4K technology (of which I am not an intimate); it easily looks and sounds as good—if not one hell of a lot better—than CD players and multi-disc format platforms costing, two, three, ten times as much. Not to say that there aren't disc players that match up favorably or raise the bar considerably—but at what cost?

Friends, the UDP-205 is that good, so much so, that I dread the inevitable call from my cigar-puffing Desert Jinn extolling the latest new formats, and the dramatic enhancements in the UDP-305. I no longer have a land line, so I can't take my phone off the hook. What's a music-lover to do?

"How ya gonna keep ‘em down on the farm, after they've seen Paaah-reee?"

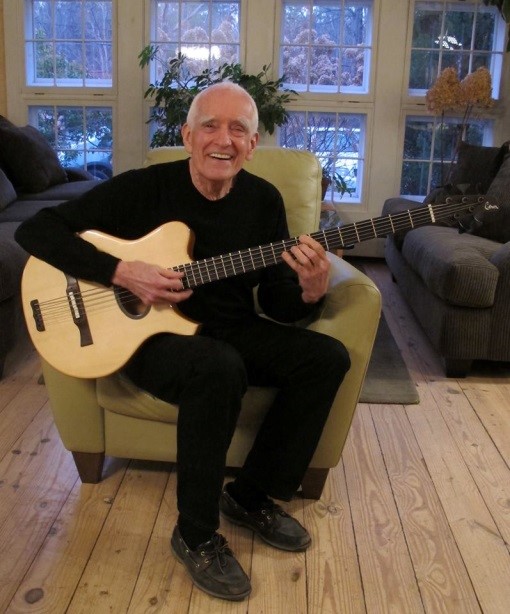

Sonny Rollins & Elvin Jones, Forever Young... We are thrice blessed that Sonny Rollins is still with us, that there are so many recorded documents which speak to his enduring greatness, and that he recorded with so many of the most innovative drummers, notable among them, a 30-something Elvin Jones way back yonder in 1957.

So, as a RADIO FREE CHIP bonus addendum to our OPPO ruminations, we choose to honor Sonny, revel in the sound of Wilbur Ware's beefy un-amplified acoustic bass and the Afro-Cuban inflections cum swing of Elvin's cathartic vamp-and-release drumming, with a performance of "Old Devil Moon" on the 60th Anniversary of the Blue Note/Rudy Van Gelder remote recordings of A Night at the Village Vanguard by sharing part of some conversations I had with Elvin one afternoon at his crib, in which he spoke of those formative years, a good three years before he commenced his iconic work with John Coltrane, and of how he just so happened to stumble on to a Sonny Rollins recording session.

CS: Did you always have that sound which you ultimately manifested with Coltrane in your mind's ear? Or were you always working towards finding the right context where you could implement your conception of how to hear the band? For instance, on those Blue Note Village Vanguard sessions with Sonny, I first heard those a number of years after I'd heard the entire range and breadth of your work with Coltrane, when I guess certain of your thoughts had crystallized and come together.

Because on Sonny's music your playing is very combustible and exciting. I was always very inspired by the manner in which you and [bassist] Wilbur Ware handled the vamp and release transitions from an Afro-Cuban vamp to a swing release on "Old Devil Moon." That's a wonderful performance, but it sounds as if you're sort of reaching for it; it didn't sound like in your own mind that everything you were hearing you were quite able to get to.

EJ: Well, I tell you what, it's interesting that you should say that, because I didn't even know they were recording, and this happened at a time when I'd just gotten fired from J.J. Johnson's band [laughter], the greatest thing that ever happened to me.

CS: May I ask if he gave cause?

EJ: Well, we just didn't get along. That's enough cause for me [laughter]. We just didn't get along. These are marvelous musicians, certainly, and he's a fine man; I like him otherwise, but to work as a sideman, it always seemed to be rubbing him the wrong way and vice a-versa. So anyway, it didn't work out. We'd made this year tour in Europe.

And first of all, I bought another new set of drums then and I borrowed the money from J.J., and of course I had to pay him back weekly, like half of my hundred and fifty bucks a week I had to give back to him, so in eight weeks or so I gave him back the three hundred and then some. And so I was living in Europe, and covering hotel bills and food on seventy-five dollars a week—that wasn't very much. And of course that kept me in a state of high tension [laughter]. Hunger does that to you. So then, at any rate, our last gig was over at the Red Hill Inn in Pennsauken, New Jersey, and that was my swan song.

And so I came back to New York, back to my apartment I was living at in the Village, and I ran into one of my brothers. So he saw me with my long face and said, "What's the matter?" And I didn't want to talk about it too much. So he said, "Well, come on—let's go out and get drunk [laughter]." So we started wandering around. And we got to Seventh Avenue…I don't even know where we were going. I think we were heading for the Eighth Avenue subway so that we could take the A Train uptown—and I think that was our motive for wandering that way.

And we came out there on Greenwich Street by the Village Vanguard and Wilbur Ware was standing outside under the marquis, and when he spotted me he said, "Jonesy! Sonny's looking for you." And I said, "Sonny who [laughter]?" I didn't know Sonny. So Wilbur said, "Come on downstairs—he wants you to play with him." I figured we could go down here and get a drink here just as well as anywhere else. So we went down the steps. And Pete LaRoca and Donald Bailey were playing—that was his regular trio. And I thought, "How am I going to play? Pete LaRoca's playing. What am I supposed to do?" So at any rate, as it turned out, Sonny wanted me to play that set with him. And I did. And that's how that album came about. So those were Pete LaRoca's drums.

CS: I'll be damned. That's the exact opposite of what I thought—I thought Pete was sitting in on your drum set and that it was your gig. Because when I heard him play, I thought, "Well, Pete tunes his drums high but he doesn't tune them that high. That must be Elvin's kit."

EJ: No. I was just sitting in. And when I looked up I saw Rudy Van Gelder sitting there and Frank Wolff was standing around or Alfred Lion or somebody…maybe both. And I said, "Well, I'll be damned—they're recording." So that's how that came about. They gave me exactly seventy-five whole dollars for that. I should have had it framed, but I needed the money [laughter].