There's an old adage folks like to dust off whence we suffer some loss, as wrenching as it is inexplicable, not unlike a late April ice storm, midst that initial gush of springtime bloom, which heretofore has served to affirm the promise and wonder of life and renewal after such a long, harrowing winter: "They say only the good die young."

©Mandala by Mary Morgan Stern/Collage by John Potis

Be that as it may, from time to time, the ill-tempered Desert God of my Old Testament Tribe is apparently willing to sign off on a few exceptions of such profoundly creative temperaments, that one is tempted not only to embrace the notion that there truly is a Divine Intelligence, but that He-She-It has exquisite taste.

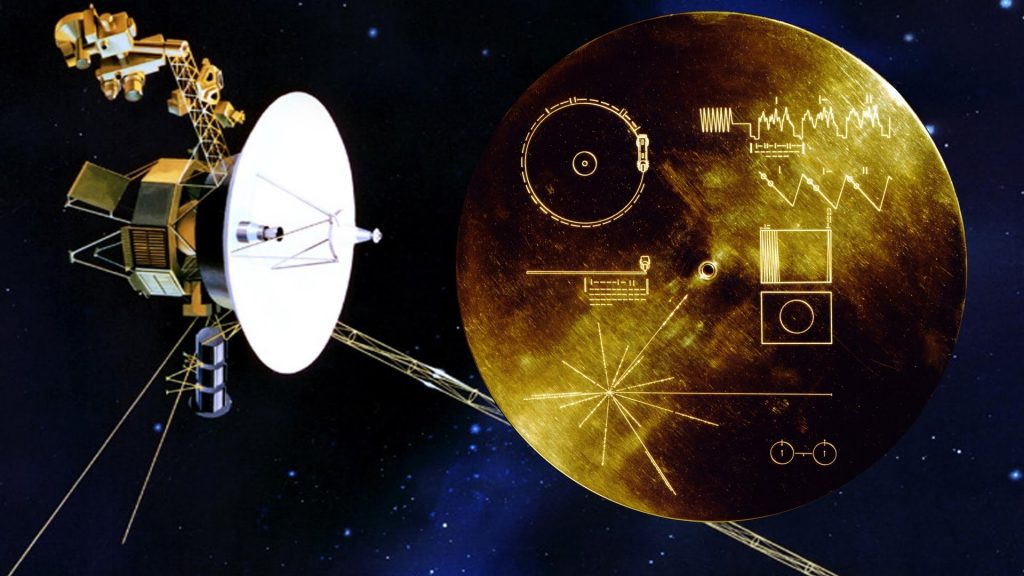

Which puts one in mind of a Steve Martin joke from an early episode of Saturday Night Live, wherein our Weekend Update correspondent reports upon the very first confirmed communiques from extraterrestrials, who responded enthusiastically to the Murmurs Of Earth gold LP that was included on both Voyager Spacecraft missions into Interstellar Space (containing greetings to our new friends in a representative sampling of global languages, and an eclectic playlist of music from Earth's different cultures).

And what was the import of that historic first message from our extraterrestrial friends?

"Send more Chuck Berry."

America's preeminent composer, Elliott Carter, was born in Manhattan on December 11, 1908, and had just turned 102 back in 2010 when I first began tracking my personal recollections, at which point he was not merely alive, but very much ticking and kicking—expanding every morning upon a post-modernist language of his own making.

Then, as now, to get lost in his uncompromising music was a transformational experience at once expressive of the tumultuous American century he helped define: intricate psycho-dramas that placed enormous demands on performers and listeners alike; which garnered him two Pulitzer Prizes for composition, when this lifelong New Yorker finally passed away in his Greenwich Village neighborhood a month shy of his 104th birthday on November 5, 2012.

After World War II, Carter began to fashion a decidedly personal rhythmic and harmonic language that was as old-fashioned as it was visionary—and decidedly avant garde. The music of this committed modernist often conveys the a sense of the overtone series itself morphing on up and out and into infinity, while his juxtaposition of tempos and ever-changing metric shifts portray a dizzying multiplicity of voices that never quite subsume the voice of the individual, struggling to find their place in a world all too complicated to fully comprehend.

Imagine the outer reaches of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie's soaring rhythmic syncopations and contrapuntal variations, without reference to the Earth's gravitational pull, let alone an incessant clockwork reference point or cyclical harmonic guideposts…the motion of the ocean, airborne creatures who've never known the touch of land—verily, the background noise of the big bang.

While Carter found much inspiration in the work of iconoclasts such as Charles Ives and Edgar Varese, he was nevertheless fully grounded in those European traditions which emerged from medieval chant through Baroque counterpoint and classical sonata form, culminating in the likes of Gustav Mahler, Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg. Which is hardly surprising for such a studious, ambitious fellow, who though drawn to modernism and personally encouraged by Mister Ives himself, studied in Paris with the great Nadia Boulanger and subsequently spent the first forty years or so of his life working his way through elements of neo-classicism and Americana (a la Aaron Copeland), before decisively setting out on a path all his own after the harrowing chaos of World War II signaled that all bets were off.

You see, Carter was not only profoundly moved by what has come to be called, rather disdainfully, 20th century music, but by the coming of radio and recorded music; breakthroughs in psychology and the science of the unconscious mind; by Einstein's recasting of our Newtonian concepts of time as an orderly clockwork universe—as well as by all of the progressive streams of modern jazz, modern literature, modern painting, modern cinema and modern poetry with which post-industrial man made such a wrenching break with the previous two thousand years.

When Mister Carter first burst upon the 20th century in 1908, not only could he recall his first encounters with these new-fangled phonograph records, but coincidentally that was the same year as the initial rollout of the Ford Model T; and in bicycling all the way downtown to the Battery from his parents' home on 114th Street in Northern Manhattan, he hardly encountered a single car along the way and back. "My generation…was the first generation to grow up with modernism. Actually modernism was a desire to find a more emphatic and stronger way of presenting in the arts, life as it was lived in the present time. And there was this influence of psychoanalysis and this influence of machinery; we could fly, we could take automobiles and all of this changed our view about how one thought about music."

Abstract sounds such as Carter's—paralleling as they do the literature of James Joyce and the paintings of Pablo Picasso—very much reflect the conundrum of contemporary man: to maintain one's individuality amidst a diverse and seemingly unconnected swelter of voices; to reconcile the inner dialogs of our conscious and subconscious mind midst all the modern world's confusion; to work, if not in pure harmony, than in some loose manner of cooperation, amidst a constantly changing chorus of contrasting voices and conflicting rhythms, without falling into some sort of robotic lockstep—one thing commenting upon another, unto infinity—to reveal the underlying vibrations of the universe, and to make sense out of the illusion of…time.

"Of course the modern world is having a hard time being modern," Mister Carter once noted dryly.

Never heard of him? Follow this link to Counterstream Radio for a comprehensive interview with Mister Carter conducted by none other than Grateful Dead bassist-composer, Phil Lesh. This is a fine place to start.

Does all of this sound as if it would take you too far out into the deep end of the pool? Are you a-feared of descending into a maelstrom from which you might never return? Ah, ye of little faith…no sense of adventure—you'd rather linger a while longer with the mob, waiting for the bouncer to lift the velvet rope and let you in, thus confirming that you belong.

You think the likes of Bob Dylan or David Bowie or Prince gave a rat's ass as to whether or not THEY BELONGED?

Rather than engaging in some in-depth characterizations of Carter's music, I should rather you discover this brave new world of sound for yourself; to accept the demands it places on one to be an active, engaged, intrepid listener; to juggle a multiplicity of tonalities and rhythms and textures all at once…much as a host of listeners and concert-goers did in celebration of Mister Carter's 100th birthday through numerous recorded tributes and live performances—culminating in a glorious concert I attended at Manhattan's Merkin Hall in December of 2008, graced by the presence of the composer himself and such devoted champions of his work as the great pianists Charles Rosen and Ursula Oppens.

Let me instead share some personal vignettes and one very special encounter with Mister Carter himself, which upon reflection seems a blessed, privileged event—borderline mystical in its way. I shall also point you in the direction of some wonderful stocking stuffers, such as a fascinating DVD documentary and some provocative YouTube links with which you may begin your journey of discovery, inconveniently located at the deep end of the pool…but first, in the spirit of Mister Carter, a roundabout parenthetical prelude.

During my days as a humble ferryman guiding my charges upon the Stygian waters of New York's City's five boroughs (okay, so I was a cab driver), I often soothed my frayed nerves, and those of my customers, with some thoughtfully programmed music. As a rule, people were not expecting to step into a clean, air-conditioned cab on a humid summer day, only to encounter some peaceful, engaging music and a driver who was neither a demolition derby jockey nor an embittered sociopath speaking Farsi and off his meds.

I tried not to blast my music, nor to feature large scale sounds that would clobber the unsuspecting customer and impinge upon their space. Still, I wasn't about playing background music, either, and I was always fascinated to observe how certain musical selections exerted a profound effect upon people, so much so that they would often spot me a significantly larger tip—my biggest money-makers being jazz pianist Herbie Nichols' Trios, the Louis Armstrong Hot Fives and Hot Sevens (with Earl Hines), solo acoustic guitarists such as Andres Segovia, Julian Bream, John Williams and Michael Lorimer, and delta bluesman Robert Johnson.

People were particularly thunderstruck by Johnson's blues, emerging as they did like some specter from beyond this mortal coil: "Who is that? Is he alive? Can I buy it?" was a typical response. I particularly cherish one encounter with this little sparrow of a woman, an elderly German lady, late one winter evening, doing her level best to hide this tiny dog in the crease of her overcoat, for fear that the bad old cabbie would give her the bum's rush, as Robert Johnson sang "Me And The Devil Blues": "You may bury my body, down by the highway side (babe, I don't care where you bury my body when I'm dead and gone); you may bury my body (ooooooooooooooo) down by the highway side; so my old evil spirit, can get a Greyhound bus and ride."

I always got a little verklempt when listening to Johnson intone his own epitaph, but on this particular night there was an added element in play, because my diminutive sparrow had surely caught the spirit, and I could hear this low, soulful moan emanating from the back seat, as she hummed along like an old delta bluesman, and it wouldn't have been much of a stretch if she suddenly burst into exhortations of "Well, well, well…" When we got to her stop, she poked her head through my partition—even as the little dog poked its head through her scarf—wherein she paid the fare, tipped me generously, and offered her sincere thanks: "Dass vas sum v-really gut musik."

Yes, music can have a profound effect on people, particularly the mysterious, the inscrutable…the unknown. But then New Yorkers always exceeded my expectations when it came to close encounters with straight-no-chaser, uncompromising sounds.

And while I was not looking to scare anyone, I was not above some occasional shock therapy, and if I were in a foul mood—which was often—rather than take it out on my customers, when cruising by myself between fares, I might play Albert Ayler and Don Cherry's performance of "Vibrations," Robert Johnson's "Stones In My Passway," the Sex Pistols' "God Save The Queen," James Brown's "Cold Sweat," the Max Roach-Cecil Taylor duets or Elliot Carter's "Changes" dozens of times in a row, until I was purged and able to lather down—but rarely in front of the customers, God forbid.

I mean, once, when I was obsessing over the solo guitar abstractions of Carter's "Changes" in front of an out-of-towner, the young man politely cut the trip short, and gave me a pretty righteous tip, though the shell-shocked look on his face suggested that he deemed it prudent to get out of my Crown Vic before I went Travis Bickle on his ass.

There was however one day of the year when I indulged my love for modern music without fear of dire reckoning, taking a defiant love it or leave it stance, and fittingly, that day was Halloween.

"Why are you playing this?" a young man queried in earnest disbelief one evening as I set before him a generous serving of Captain Beefheart from Trout Mask Replica. "Don't get me wrong, driver" he added, "I like it, but what's the point?" Recalling a Joe Flaherty character from one of those old SCTV skits, I answered in my best Count Floyd imitation: "Pretty scary kids, oww-wooo…" He laughed as we concluded a pleasant ride across town to the Upper West Side—which by a commodious vicus of recirculation, not unlike how the composer structures his music, brings us back by to Mister Carter and environs.

Now this one particular Halloween, I got out on the early side of the night shift. And as the afternoon daylight illuminated a breathtakingly clear, cobalt blue sky, I decided to start off my Count Floyd Mix with the First String Quartet, from Elliott Carter: The Four String Quartets by The Juilliard String Quartet (Sony Classical). This work was introduced back in 1951, around the time I was still lollygagging about in my mother's uterus, and it is often cited as a seminal breakthrough in the composer's free flowing, conversational use of multiple tempos and metric shifts—the blossoming of the unbridled modernist aesthetic which defines his work of the past 60 years and which had drawn him to the likes of Stravinsky, Ives, Varese, and Schoenberg as a teenager (and which first forthrightly revealed itself in his breakthrough 1948 composition, Sonata For Cello and Piano).

David Harvey has written that "Given the style of Carter's previous works, it might have come as a surprise to the Quartet's first audiences that its musical language is not at all superficially ‘American' in spite of the quotations from Charles Ives' Second Violin Sonata (in the first movement) and Conlon Nancarrow's First Study for Player Piano (in the last)."

Well, my first fare is a 40-something business woman, elegantly attired, who hailed me by Grand Central and who wants to make a short trip down Lexington, and form there, to proceed East on 38th Street. The Carter String Quartet was playing when she got into the cab, and we proceeded without comment. Next thing I knew, so bathed in alpha rays was your narrator that I blundered past 38th street, though my fare didn't notice it. I turned off the meter and apologized for driving right past her street.

©Mandalas by Mary Morgan Stern

"I'm sorry, Miss, but I guess I was absorbed in the music," I explained. "So was I," she responded with some passion, as if wakened herself from a deep reverie, and after I circled back around to her drop her off in front of her building, she gave me a really righteous tip. Go figure. My next passenger was an older Jewish lady heading back over to the west side, and after a few minutes, she asked me what this music was. "Does it bother you miss?" I asked timorously. "No, not at all," she enthused. "It makes me think of the chase sequence in some foreign film."

Chalk up another big tip. The next passenger, yet another woman, heading up Eight Avenue, listened for a few minutes then laughed, "Only in New York City could you step into a taxi cab and find the driver listening to Elliott Carter." It turned out she was in the music business, and was Andre Previn's manager—a composer, conductor and piano player of considerable talent and acclaim. Another big tip, and a young man with a beard gets right in as she steps on out, heading across town and down Ninth Avenue.

"So, you dig Elliott Carter" he exclaimed, and proceeded to recommend some of his favorite Carter pieces, and confided as to how in the near future the composer was due to premier his very first opera ("What Next?"). Here I was half expecting an armed insurrection, and instead received an enthusiastic thumbs up from four very engaged passengers. Maybe our disposable pop culture doesn't give people enough credit for what's between their ears.

How then had I come to choose Elliot Carter as the featured artist for this late 1990s Halloween ritual? Funny you should ask.

A summer or two before, while driving on a Sunday afternoon, I was trying to make my way around all of the damn street fairs and parades that typically gum up the works on what should be such a quiet, relaxed day. Finally in frustration I headed uptown on Broadway, fixing to make a pit stop in the little boy's room at a gas station on 126th Street, and hopefully to circumvent the chaos downtown. As I approached the gates to Columbia University at 116th street, I was flagged down by a young man, who was hailing a cab for two very elderly people. After helping them into my cab, and a cordial exchange of goodbyes, much to my chagrin the old man requested I take them to 10th street in the Village, between Sixth and Fifth Avenues…YIKES…right back into the belly of the beast. Sigh.

I gathered from snippets of their conversation that they'd just attended a Beethoven recital of some sort at Columbia. Then as I made my way down West End Avenue, I overheard the man invoke the name of Conlon Nancarrow, another American original, whose rhythmically dynamic compositions for player piano are well out of Earth orbit.

Me, being a natural busybody, saw an opening with which to toss my two cents in: "Conlon Nancarrow sounds like the illegitimate son of Cecil Taylor and Willie ‘The Lion' Smith," I opined.

The old man just perked right up. "Did you hear that dear," he enthused to his wife, "the driver knows who Conlon Nancarrow is. Did you know Willie ‘The Lion' Smith, driver?" He had me there. "No sir, not personally; that's a little before my time, but I know his music."

Soon enough, the cumulative carnage spilled over on to West End Avenue, and we were stuck but good. Not surprisingly, frustrated by the traffic, the old man began to politely query me as to alternate routes; my own bladder ablaze, I offered to take any route he liked, but my sense of things was that we would be okay once we got below 72nd Street, and he quietly relented. Then, as we passed an elder hostel further down West End Avenue, his wife got testy and blurted out, "Look at all of those old people," which was pretty damn funny coming from a woman who looked to be 90 if she was a day. "There now, dear," her husband offered soothingly, "they're just elderly."

Finally, we made it past 72nd and I tried to make up for the all the time we'd squandered in gridlock. "How are you going to proceed now, driver?" the old man asked solicitously, and again I offered to take him any way he wanted, but indicated that I thought 46th street would get us cross-town without incident, and from there it'd be a straight shot down Fifth Avenue.

"Do you play an instrument driver?" his wife queried, and when I told her that I played drums and guitar she asked if I still played; I indicated that I did whatever was necessary so as I could remain in close proximity to music every chance I got.

Quickly shifting gears, she allowed as how "You're a very good driver," but before I could thank her, she asserted that "I used to drive a taxi cab." Well, good for you, I responded, but as we turned down Fifth Avenue her husband felt compelled to let me in on the joke: "I'm afraid she is pulling your leg driver," he chuckled. "But she did used to drive in Manhattan," he added. "And how," she blurted out adorably in the lexicon of a ‘20s flapper.

When I finally got them to their apartment building, I reckoned they could use some help getting out of the cab, and while the old man exited on the curb side, I went over to the street side, where the old lady was kind of trying to rock herself upright. "Here darling," I said, extending my forearm, "Let me offer you a helping hand—one cab driver to another."

She smiled broadly at me as she made her way around the back of the cab, crossing paths with her husband as he came back alongside to pay me. When I made eye contact with him a little bell went off in the back of my head. "Gee, sir, you look familiar—are you a composer?"

"I'm Elliott Carter," he said simply, at which point I took off my fedora and banged my head against the roof of the cab like the schmuck I was… here I'd had J.S. Bach in my back seat and I hadn't really engaged him…and me a devout music person, for God's sake.

At which point I vainly tried to crowd about an hour's worth of enthusiasm into roughly 30 seconds, as he made his way back to the street and his waiting wife. I told him that we had a mutual friend in pianist Ursula Oppens; he smiled broadly and expressed genuine enthusiasm for her musicianship. At which point his wife came up to me, affectionately embracing my hand in both of hers, thanked me for a lovely ride and added consolingly, "Everything will be all right, young man, you'll see. When you have music, you have everything."

As she made her way through the entrance, Mister Carter thanked me for being so nice to his wife, and politely sought to take his leave of this wide-eyed groupie, explaining that he had to attend to her. I concluded by telling him how I'd once taken a pass at his composition for solo guitar, "Changes," but that after about four bars I realized I was in way over my head: "Man, it just fried my mind." Mister Carter nodded knowingly, and allowed as how "It is really quite difficult," as he made his way to the front door. At which point, he stopped, did a comic double take, and turning on his heels, addressed me one last time, with a solicitous smile on his face: "I'm sorry."

While ferrying passengers across the Village over the next couple of years, I used to see Mister Carter and his wife walking along 10th Street, and one time when my taxi was empty, I took the opportunity to call out after him and Mrs. Carter in a real Mel Blanc, toidy-toid-and-thoid kind of Brooklyn field holler. They stopped and listened oh so politely as I recalled our cab ride, and they wished me well.

I subsequently waited patiently after the Merkin Hall Concert in December of 2008 to shake his hand, remind him of our meeting, and to thank him for all of his inspiration as a player and as a listener. Of course our meeting was but a grain of sand in the greater hourglass of his century and counting upon this planet, whereas it was as vast as the Sahara in mine own mind's eye, but I was grateful that I could wish him a happy hundredth birthday, and that I'd been able to experience such an intimate encounter with the likes of Elliot and Helen Jones-Carter.

Helen Jones-Carter passed away during the filming of Elliot Carter - A Labyrinth of Time (2004), a revealing documentary about the man, his times, and his music, by director Frank Scheffer, who was introduced to this extraordinary man and his remarkable body of music by his good friend, a famous Elliot Carter-enthusiast, guitarist-composer Frank Zappa (who during his formative years was likewise inspired to become a composer by one of Mister Carter's own inspirations, the iconoclastic composer Edgar Varese). Besides A Labyrinth of Time, Scheffer has produced several documentaries on major musical figures of the 20th century, including Conducting Mahler (1995), Frank Zappa: Phase 2 - The Big Note (2002) and Varese: The One All Alone (2009).

I must confess to being unfamiliar with these works, a faux pas which will be remedied shortly, but for any of those who might be curious about Elliot Carter's music, this film is simply a gem. Visually, in its conception and execution, it is something of a metaphor for Mister Carter's music, offering intimate but subtle insights into his thought process; the historical context and evolution of his sound and the plaudits of admirers such as Charles Rosen and Pierre Boulez. Scheffer does a wonderful job of illustrating how the poetic, humanistic qualities of the man are reflected so vividly in his art.

In closing, the evocation of Helen Jones-Carter's passing, and the dedication of the film to her memory, is handled with great simplicity and dignity, her abiding presence in Mister Carter's life reflected through unspoken shots of her sculptures, and dream-like juxtapositions of Elliott's thoughtful visage against the backdrop of his beloved Brooklyn Bridge, which like the man himself, speaks not merely to its time, but to the ages.

"In the end," Mister Carter concludes, speaking from the perspective of a man whose life straddled the dizzying transformations which mark the transition from the old world of the 19th to the brave new worlds of the 20th and 21st centuries, "what we're living through at the present time is kind of strange; a mixture in confusion will wear itself out and that people will become much more sensitive and aware than they are now.

"They will have to be, because as society becomes more complicated, more full of people and more different kinds of things happening, people will have to become much cleverer and much sharper—then they will like my music."

©Mandalas by Mary Morgan Stern