MUNICH → TOKYO → KRAKOW

This is the story of how wireless, in-ear headphones belonging to the top-of-the-line "8000" series, model ZE8000, turned into my personal headphones, not only in the sense that I became their owner, but that they were personalized specifically for me. And it's not at all about cosmetics, appearance or equipment. It gave me the opportunity to experience what high-end service looks like.

Final Audio, formerly using the name Final Audio Design, is a Japanese brand known since 1974. Its first product was a Moving Coil cartridge, designed by Mr. Yoshihisa Mori. For a short time Final offered turntables, amplifiers, and speakers. In recent years, it's a company associated primarily with headphones. Its chief engineer is Mr. Kimio Hamasaki-san.

Walking around the halls, booths, and rooms of the Munich High End Show 2024, I was in no hurry anywhere. Events of this type are so huge that visiting every exhibitor would require extending the event to ten days, if not more. As one can easily calculate, listening to music at each of them and talking to selected representatives is an impossible task. After all, the MOC area covers more than 30,000 sqm and exhibiting 513 companies showcasing 800 brands and many thousands of products; more HERE.

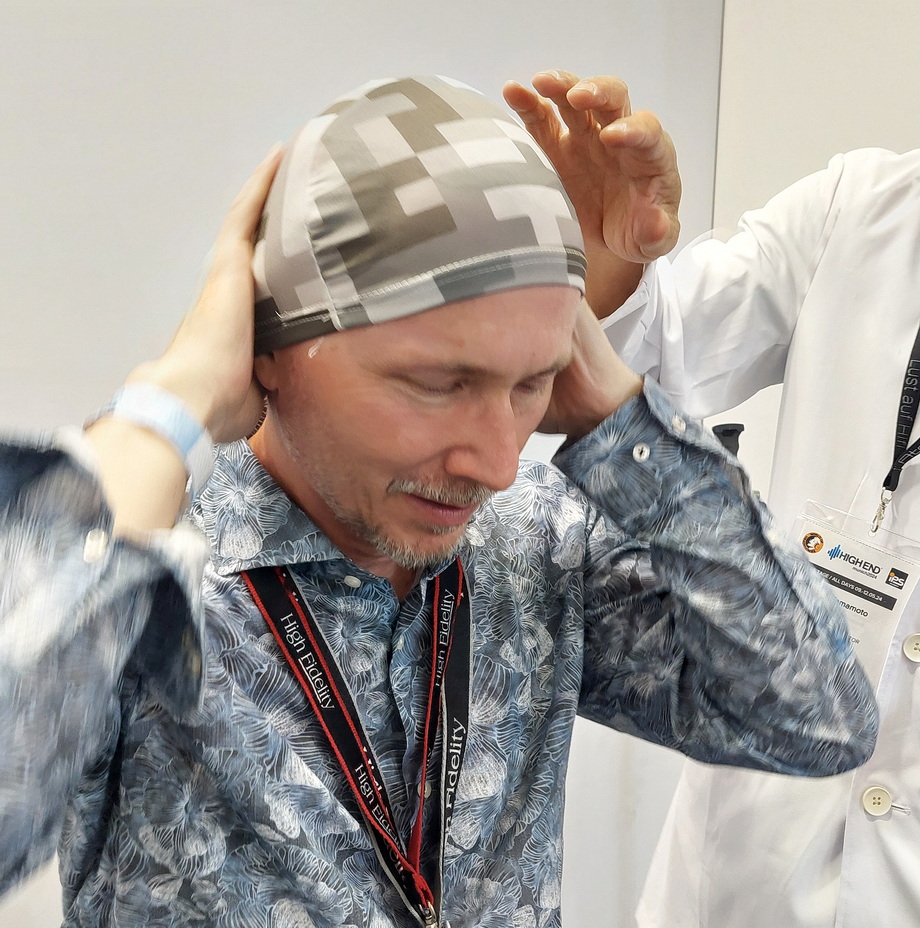

Yours truly puts on a cap to help scan his head.

That's why, for several years now, I don't rush anywhere. I wonder around the MOC, surrendering to the rhythm of the event, stopping if something piques my interest and indifferently passing by events that seem boring, pointless or that simply don't interest me. In a sense, I relax.

Especially since I always try to find time to pop into town, have a coffee at a restaurant just off Marienplatz on the fourth, if I'm not mistaken, floor, or pop into one of the larger record stores I know, overlooking the Neues Rathaus. This year, in addition, I returned to the Alte Pinakhotek to see, once again, the incredible, mesmerizing Autoportrait in Fur (German: Selbstbildnis im Pelzrock, 1500), a painting known from countless reproductions, as well as da Vinci's magnificent Madonna of the Carnation, 1475.

But mostly at audio shows, including the one in Munich, I meet people. Or they meet with me. That was the case this time, too, and one of the most interesting and stimulating meetings was the one that resulted in the column you are reading.

I HOW IT ALL STARTED

At the beginning of the event in question, we bumped into each other with Mr. Nobumasa Mori-san, head of Fonnex, which is the Polish distributor of several Japanese brands, including Final. We were happy to see each other, because we hadn't seen each other in a long time (in Munich I meet a lot of friends from Poland with whom there is no time to see at home), but Mr. Nobumasa quickly asked me if I had time, because he would like to show me something really cool. Just moments later I was scheduled for some sort of meeting (presumably in the beer garden), so we agreed that I would come in an hour or two. And I did come.

I was greeted on the spot by Mr. Satoshi Yamamoto-san, Final's sales manager, dressed in a doctor's smock to emphasize the dual role he was playing, that of ENT specialist and scientist. After saying hello, he asked if I would like to listen again to the ZE8000 headphones I had tested some time earlier, but with brand new software. Of course I wanted to. So in a moment, I was sitting in front of Mr. Satoshi-san with a cap in camouflage squares on which was attached a small block clad in the same fabric as the cap. The sight was so idiotically funny that we immediately took a few pictures, which I sent to my friends.

The abbreviation JDH, or Jibun Dummy Head, is applied to the headphones

Thus began something that didn't have its finale until late June. That's when I received a shipment from Japan, which included ZE8000 headphones with the JDH abbreviation on them, the expansion of which is: Jibun Dummy Head, freely translated: "My own personal artificial head"; 'jibun' - 'someone else's, my own,' your own,' depending on the context, and in one of them has the same meaning as the decidedly masculine 'watashi.'

What is it all about? JDH is software that is designed to bring listening through headphones closer to the experience we have listening to music through speakers. However, it's not a simple audio "spatialization" program, even as advanced as the one in the dCS Bartók APEX Headphone DAC, which we test in the same issue of High Fidelity.

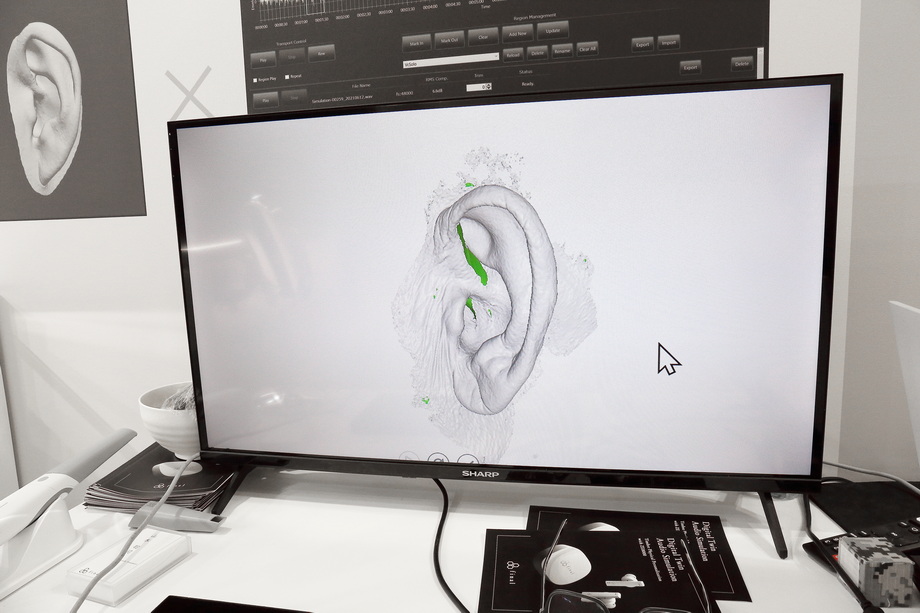

This is a full simulation of the reflection, refraction, masking and amplification of the sound wave that occurs when listening to music through speakers. To achieve this, the upper torso of the listener is scanned, and then the auricles themselves. A program specially written for this purpose allows these corrections to be made to the headphones' DSP processor. The result is a "Personal Dummy Head." At the time of writing this article, the service price for the people outside the industry was not set yet, but we knew the price under consideration - it is expected to be around 55,000 yen, which is quite a lot (that's about $1,350).

Dummy Head

The Dummy Head is, literally, an "artificial head," a dummy used to make binaural recordings. As I wrote in the article. Binaural. 120 Years in the Realm of Headphones, listening with them differs in significant ways from listening with speakers; full article HERE. With them, the effect of room acoustics on the sound is eliminated, and specific changes in the signal caused by ITD (interaural time difference) and ILD (interaural level difference) are eliminated.

Neumann KU-100 dummy head photo press material by Neumann, HERE

ITD and ILD are phase shifts and loudness changes caused by the distance between the ears and the anatomical structure of the nose and ears, which make us hear spatially. They are referred to as "head shadow;" that's head-related transfer function (HRTF). In short, it consists in the fact that when listening through two speakers, both ears hear both channels simultaneously, but differently. The left ear directly the left channel and the HRTF-modified right channel, and the right ear directly the right channel and the HRTF-modified left channel (more HERE).ITD.

So binaural recording techniques, that is, simulating human listening, have been developed specifically for headphone listening. Artificial heads with modeled ears, inside of which there are microphones, are used for this purpose. They are manufactured by companies such as Brüel & Kjær, Head Acoustics, Knowles Electronics and GRAS Sound & Vibration. The best-known model, however, is Neumann's KU-100, used by Telarc and Chesky Records, and found in the recordings of many others. Its specific use by Tchad Blake resulted in a unique sound on the Binaural album by the group Pearl Jam (Epic, 2000).

A 1974 album by the krautrock band Code III titled Planet of Man, recorded using an "artificial head"

However, recordings of this type have their own problems. One is the completely different operation of microphones, designed, after all, to work in the open field. Placing them in the earholes causes a change in timbre and phase. Another—the Dummy Head has a particular spacing of microphones and the shape of the auricles, not to mention the head, completely different from ours. The solution proposed by Final is therefore unique—with it we get sound given in a personalized way, taking into account our own anatomy. In addition, this applies to all recordings, not just binaural or Dolby Atmos encoded ones.

II HOW DOES IT WORK

Jibun Dummy Head is a service consisting of two components: scanning a person and applying the program to the DSP of the ZE8000 headphones. The manufacturer puts it this way:

This is Final's original service that maximizes the completely new music experience "8K SOUND" of the flagship completely wireless earphones ZE8000, tailored to each individual.

A "personal dummy head" is created from detailed data obtained from the upper body of each individual using a special measurement method, and then inputted into a uniquely developed "virtual sound environment," and the obtained data is used to align the sound on the ZE8000 to suit each individual.

Acoustic physical quantities are precisely derived through physical simulations using COMSOL based on shape data measured at 864 measurement points not only on the auricle but also on the entire upper body. Final's original software controls the acoustic physical quantities of the dummy head in the virtual sound space.

Dummy head, FINAL-inc.com HERE, accessed: 25.06.2024.

The idea is based on an insight that we all know about, but which few have taken into account until now. Or even if they did, they didn't know what to do with it. The idea is that when listening to music through headphones, it's about differences not only in the time it takes for sounds to reach the left and right ears (the "massaging" effect), but also about how the timbre then changes. And, as the manufacturer writes, "timbre is the most important factor in listening to music composed of different instruments and voices."

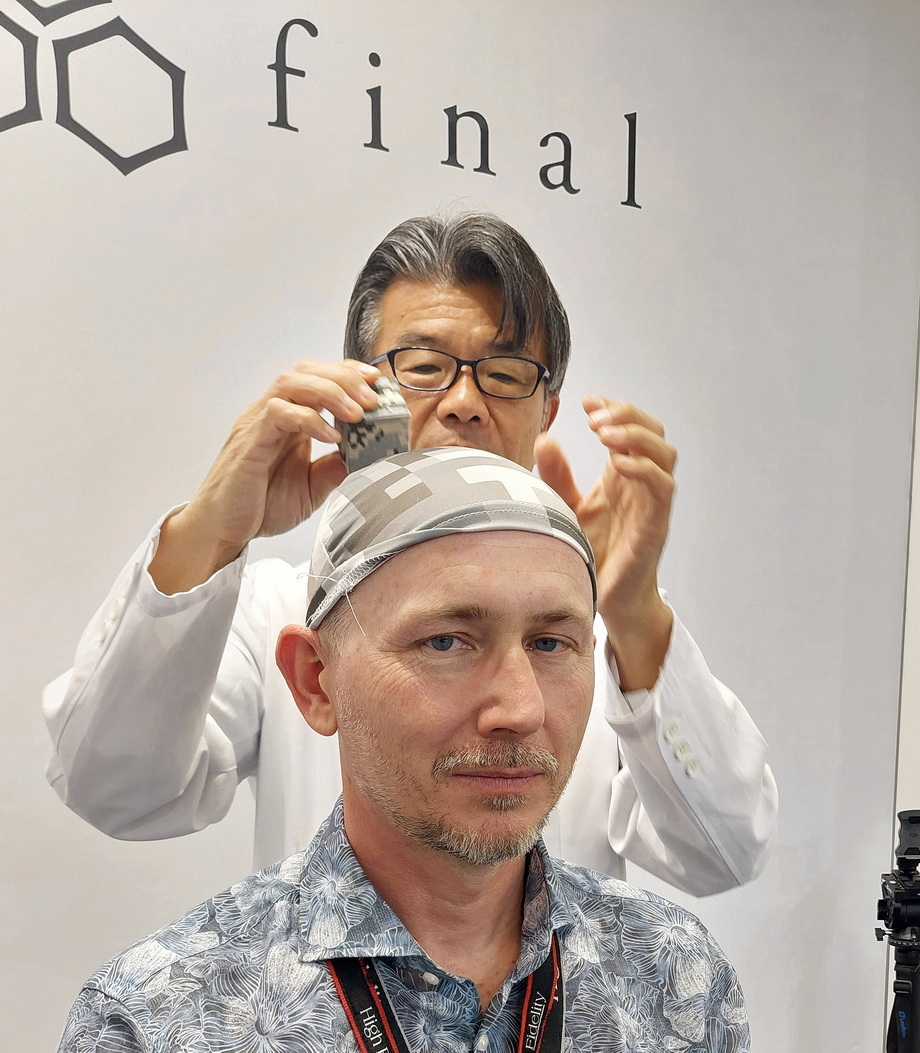

Satoshi Yamamoto-san, Final's head of sales. A moment, later I sat down in front of him, and he performed a scan of my ears.

All headphone sound-correcting systems that I know of are based on the former observation, and few, hardly any, on the latter. It takes a lot of work and money to make things work as expected. It is, in fact, a high-end service, in addition requiring the human factor, which Bartosz Pacula, privately my son, wrote about in his book:

(…) High-end service focuses primarily on a very attentive approach to the consumer. It doesn't matter whether we want to sell someone a road bike, offer them a unique overnight stay, or introduce them to an offer of fighting-cooking nannies: the key is always to be as attuned as possible to the needs of the person served, to listen to their desires, to take into account the smallest details of their lives.

Bartosz Pacula, High-End. Dlaczego potrzebujemy doskonałości, Znak Horyzont, Kraków 2023, p. 246.

In this case, "listening" to the client's desires takes on a completely different dimension, becoming a body.

DAY 1

The procedure in question here is quite complex, requiring time and expert personnel. It is divided into two parts, carried out over two days, separated from each other. In the first, the measurements I mentioned are carried out. This requires reporting to a representative who has the appropriate scanners. Today there is only one point, which is Final's headquarters in Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture; in my case it was a mobile laboratory in Munich—I was lucky. Perhaps in the future others will be established, including in Europe, but probably even then there will not be many.

After scanning us the measurements are recorded and sent to Japan, for analysis. Its basis is a paper by Gunther Theile entitled On the Standardization of the Frequency Response of High-Quality Studio Headphones, published in 1986 in the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society; available HERE (accessed June 25, 2024).

The in-ear headphones return to us in a personalized form, with a sticker informing us about the owner and a short thank you note.

Let me remind you, that Gunther Theile is head of the Audio Systems and Engineering Section at the Institut für Rundfunktechnik (IRT), a research and development institute for public broadcasters in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. He's one of the people with direct influence on our digital daily lives, as he's behind developments such as the MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 codecs, and he also headed the ITU committee making recommendations on 5.1 surround systems. As the bio on the Audio Engineering Society website reads, his recent work focuses on wavefield synthesis, 3D surround sound and binaural systems; more HERE.

Based on these insights, Final's young—their young age Mr. Satoshi emphasized several times—engineers, working under the leadership of Mr. Kimio Hamasaki-san, the company's chief engineer, wrote a program to simulate the shape of our body, correcting how it affects sound timbre. In an interview with a Japanese portal, Mr. Hamasaki-san explained it this way:

Sound is scattered and reflected when it hits the head, upper body or ears. This changes, among other things, the timbre of the sound. How does it change and how does the brain perceive sound when it is heard? The answer to this question is difficult. For example, a violinist can distinguish between the different tones of Stradivari's and Cremona's famous instruments, but it is difficult for a novice listener. Therefore, we know that experience also plays a big role in this process.

However, personal optimization doesn't have to go that far. The solution to this, theoretically difficult problem, is simple: try applying sound to an avatar with exactly the same shape as the user, measure how the sound changes according to the user's body shape, and play it back during playback. If the accuracy of the measurements and calculations is then improved, it will be possible to reproduce the sounds that the user hears every day, only that when played through headphones. The technique used to optimize the timbre in this case is our Dummy Head program.

AV Watch av.watch.impress.co.jp HERE, 7 February 2024, accessed: 27.06.2024; translated using: DeepL.

Journalists note that when the parameters obtained from measuring the user's body are stored in the ZE8000, the sound played through the headphones changes. So how is it produced and how is it changed? As we read, usually when we hear "adjusting the sound," "adjusting the sound with an equalizer" comes to mind. And then... "If all you have to do is tweak the sound a bit with an equalizer, then indeed, 55,000 yen seems like a lot of money." But... the most common type of digital signal processing is an equalizer, which uses an IIR (infinite impulse response) filter. However, the Dummy Head software in our case does not use an IIR filter, but an FIR (finite impulse response) filter. I won't go into details, but IIR requires relatively little computational processing and can be handled even by a not-so-powerful DSP processor, and the results of the calculations are immediately available, so adjustments can be made in real time while checking the changed sound. FIR filters, on the other hand, require a large amount of processing and time, so they cannot be processed in real time.

The analysis of the measurements and their input into the program must therefore be carried out "by hand" by programmers at the company's headquarters. This seems to be a rather complex process, as at least a month passes between the scan and the next step. In certain cases, it can take even longer.

DAY 2

On the second day of the procedure—as I say, it could be in a week or two or more—Final contacts the ZE8000 owner via the Internet. This time it's about the final tonal adjustment taking into account our preferences.

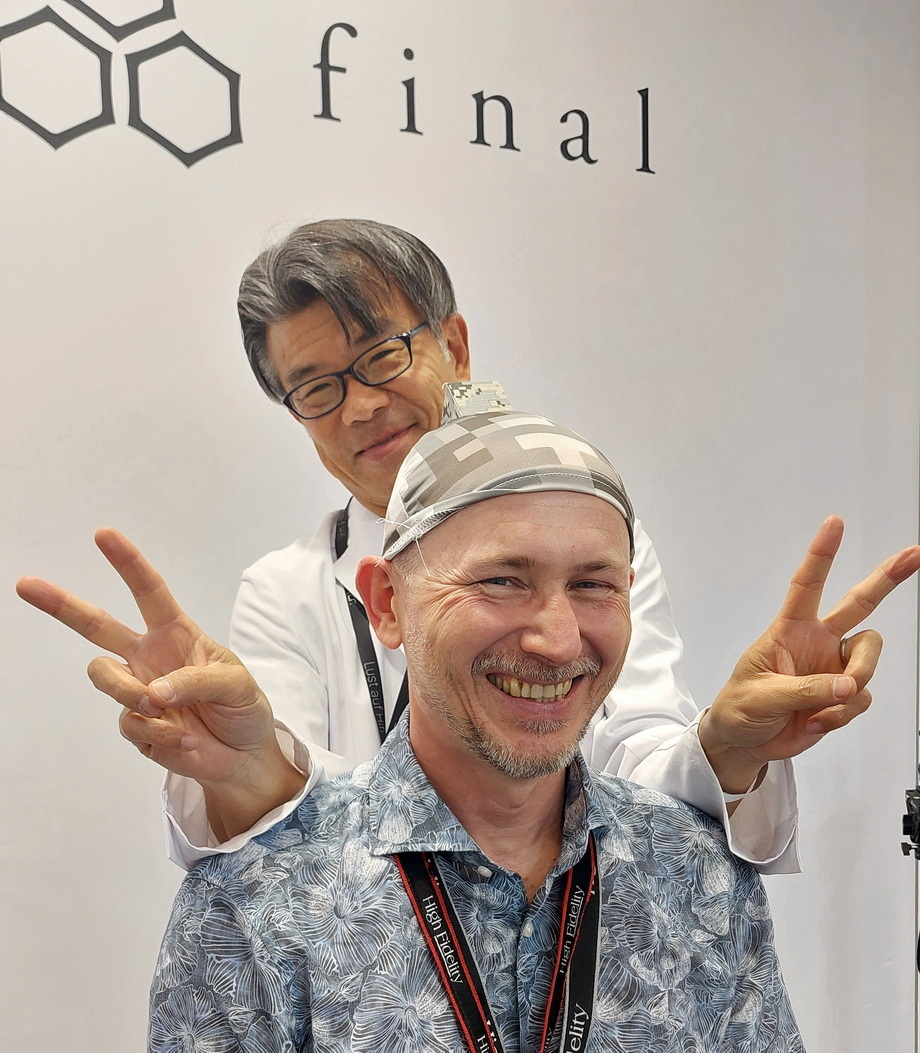

Just a small cube on the top of the head and we can start…

During the Zoom meeting, we will be asked to listen to excerpts of some tracks from different musical aesthetics, genres and types, with voice, solo instruments, orchestras and ensembles, near and far. Each example is given in three versions—A, B and C, differing in the depth of correction. Our task is to point out the ones we think sound best. We do this with the headphones we received as a replacement for our copy, sent earlier—I forgot to say it—to Final’s headquarters.

Our choices are then analyzed and as final—nomen omen—corrections are made to our body measurements. In a while, a courier will arrive with a package, in which there will be our headphones with the JDH logo and a sticker confirming for whom they have been personalized. Along with the headphones, we also receive new silicone earbuds called Dummy head. These are based on the earbuds developed for the Mk II version of the ZE8000 headphones. Final writes that they have an improved seal and better air retention, because "with constant wearing position and sound pressure it is necessary to equalize the timbre, which is the premise of this service."

III HOW DOES IT SOUND

To find out what changes the Jibun Dummy Head algorithm introduces, you need to go to the Final Connect app and open the tab titled, no surprise here, Personal Dummy Head. When clicked, it opens a page with four settings: Reference, RF None, RF+n and Off.

Our target "audiogram" is stored under the first of the buttons. In turn, under RF None and RF+n, algorithms with parameters that slightly change the assumptions of the physical impact of the acoustic virtual sound environment on Dummy Head (i.e., on our measured avatar) relative to the reference parameters are saved. RF None is the opposite of RF+n: the correction level is slightly smaller, while with RF+n it is larger. This can be set permanently or changed depending on the song. But there is also an "Off" button, which makes comparing the sound of the headphones with and without the correction algorithm instantaneous.

PAST

My experience with headphones goes back to my early childhood, when, at about three, maybe four years old, I received my first LPs with children stories. Since we lived in a 24-square-meter apartment, which was more than modest, I got headphones from my father connected to some kind of headphone amplifier he had constructed on the board.

… and ready—as you can see Yamamoto-san is happy about the results

While I don't remember what it was, I vividly remember the shape and grayish-red colors of the Tesla headphones I got in turn when the vinyl with children stories were replaced by a small Philips cassette recorder. It was from that time that a love for such wonderful fairy tales as The Summer of the Moomins and Pinocchio remained deep inside me.

The first of them, based on a theatrical performance based on the prose of Tove Janson, was released in 1978 by Wifon and Pronit (on LP and cassette); the performance was directed by Andrzej Maria Marczewski, the lyrics were written by Bogdan Chorążuk, and the music was composed by Tadeusz Woźniak. The second one, based on a text by Carlo Collodi, was released in 1976 by biggest Polish label Polskie Nagrania and directed by Wieslaw Opalka. The soundtrack was created by Ryszard Sielicki. Voice-overs were done by the most outstanding Polish actors, including Bończak Jerzy, Lipowska Teresa, Bogucki Andrzej, Emilian Kamiński.

PRESENT

This shaped me. That's why in my later musical development I frequently reached for headphones, and the point of arrival for me was working with them in the recording and production studio of the Slowacki Theater using my own Beyerdynamic DT-990 Pro in the first 600 ohm version. Today I own more than a dozen different models, from the Audeze LCD-3 to the Sennheiser HE-80.

I listen to music through loudspeakers mainly during tests, shows and presentations, as well as at meetings of the Krakow Sonic Society. Most of my time, however, is spent with headphones over or in my ears, with HiFiMAN HE-100 v2s driven by a Leben CS-600X amplifier and with Lime Ears Anima and Pneuma with a S.M.S.L CD-200 CD player. Moving around town, I use Focal Sphear corded headphones. They all have cables.

A portable scanner used to make a 3D model of my ears.

I respect, but do not desire wireless headphones. I understand their usefulness, handiness and functionality. It's a technology that dominates the modern model of music consumption and will remain so. What can't be forgotten, however, is that it is nevertheless a way of listening fraught with Bluetooth system problems. And even in the highest specification Snapdragon Sound aptX Adaptive, that is, with relatively low compression, the sound will not be the same as when listening via "cable." There's no chance of that.

However, when I come across something like the Final ZE8000, I find a place for them in my heart. As I wrote in their test, their sound was very pleasant, smooth and dense, so you can listen to music with them for a long time without getting tired. I pointed out that Final's designers had done a great job in getting the best out of the available technology. The conclusion was clear: "If I were looking for Bluetooth headphones for everyday listening away from home, the ZE8000s might be it;" full test HERE PL.

FUTURE

Having another unit to listen to, I recalled those hours spent searching Tidal's resources, and the feeling of complete comfort returned. Let me remind you that during their test I used the company's upsampler called 8K Sound, as well as a slight equalizer adjustment. It was very cool. When I got a pair of ZE8000 Jibun Dummy Heads prepared for me, I found that in no way did this experience prepare me for what I heard.

The interview referenced above talks about the equalizer settings that almost all wireless headphones are personalized with. It really works and is helpful. So it would seem that the optimization proposed by Final would boil down to just such—perhaps more detailed, more sublime, but still—correction. Nothing of the sort—the changes in the sound of the ZE8000 come at an absolutely fundamental level, and the timbre correction only serves to "anchor" them to our sense of "real sound."

What the personalization of the sound of these headphones gives you is stunning. Literally. At the first moment we don't know what to pay attention to and we even wonder if we are sure everything is right. For here is the adjustment we are dealing with is fundamental and forces on us a change in our habits and expectations of headphone listening.

I started with an evocation of my childhood for a reason—I wanted to show that the pattern of "headphone sound" is inherent in my body. That is why the first contact with the sound prepared based on the measurements of my person was disorienting for me. However, I quickly got used to this new sound. So much so that I just as quickly stopped switching between the "Reference" setting, i.e. with the correction algorithm, to "Off", i.e. without it. Anyway, in the latter case I could not use the upsampling, now part of the whole algorithm.

A nearly finished scan of the left ear; the green color indicates parts of the auricle not yet examined.

The sound with the Final headphones is flawlessly spatial. There is a clearly defined depth of stage, there is a wide panorama, and finally there is what we call panorama or stereoscopy in speaker listening. None of the third-party spatialization software comes even close to this. And rendering space in this type of environment is incredibly difficult. Manufacturers do it in various ways, and that is by tilting the drivers, as in Crosszone or Ultrasone headphones, and once in the famous AKG K1000, sometimes they also use passive components, as in Beyerdynamic DT-990 Pro. Others, finally, rely on DSP processing.

But the Japanese company gives us something completely different. The space, with its fantastic detail, tonal dynamics and "breath" that I got from the ZE8000 was downright moving. I perceived it regardless of what kind of music I was dealing with. Because even mono recordings benefited from it, presenting a much clearer, three-dimensional bodies of vocals and instruments. Which reminded me that this was exactly the kind of thing Mr. Koji Tono, who from 1980 to 2023 was one of the heads of research at Sony, mainly in the headphone department, was talking about.

In an article just published on its website, Stereo Sound magazine writes:

In my experience with headphone sound design, I was always conscious of creating a sound that would allow a wide image of the sound space. The sound source you listen to with headphones is adjusted for speaker playback, and when speakers placed in a room play music at a certain distance and with the indirect sound of the room, the sound is filled with an appropriate sense of space and richness. However, when playing this sound source with headphones, it is difficult to reproduce the sound elements of the room's space, so for headphones, I aimed to create a sound that would allow you to easily imagine the sound image from a distance.

Koji Tono, The birth of the Walkman and the CD was the catalyst for the evolution of Sony headphones. Looking back at the beginning (Things you should know about headphones 01), Stereo Sound, 27-06-2024, online.stereosound.co.jp HERE, accessed: 27.06.2024.

To some extent it succeeded, and the 1989 Sony MDR-CD900ST professional model was exceptional in this regard. But even it doesn't have anything like the space provided by the modified Final headphones. It's a realistic, three-dimensional soundstage, with a foreground—finally, I don't have to write 'foreground' in quotation marks—and wide edges.

And at the same time their timbre is also rich, deep. The sound is much more open than without the algorithm. Turning it off and boosting the high-frequency EQ also opened up the sound, but rather in the sense that it brightened it up. And the Jibun Dummy Head opens without brightening. There's bass here, too, although it's more distant than in classical listening. That's because it doesn't hit the head, but is moved beyond its outline, as if the musician were really standing on stage.

And there is something else—I don't know if you remember, but I once wrote about surround systems designed for headphone listening, including Dolby Atmos. And maybe also, that I'm not a fan of this solution, since most of the material is an automatic render, not a separate mix for headphones; more HERE. With the modified Final headphone software it finally started to make some sense. Because the sound was substantive, powerful dynamic, really interesting.

On the second day, after the torso and ears are scanned - left side - final adjustments are made using excerpts from musical pieces - right side. photo Final

This is why I believe that Final's solution should be licensed to all companies offering headphone amplifier DACs. The processing in question is done in the digital domain, so it would be a shame to go from analog to digital and then back to analog (AD → DA). Unless we treat such a solution as a "black box" and listen to the turntable this way as well. Because this may be the future of headphone listening. Certainly with high-end wireless models, and someday maybe with cabled headphones.

If this kind of personalized approach to a customer who doesn't want to spend millions yields such spectacular results, why is it a niche approach? Why is it so rare to find a high-end service for virtually everyone in this industry (neither the ZE8000 nor the cost of personalizing them are all that high)? To answer, I will once again quote an excerpt from the book High-End...:

Ultimately, each of us will have to answer the question: then, is the realm of premium services really high-end? Or does the reality in which most of us operate, simply works poorly, belonging to the low-end domain? And if so, what does this tell us about the modern world?

Final shows that with knowledge, persistence and a bit of madness in your blood you can change this world a little. Improve it.

text by WOJCIECH PACUŁA

images by High Fidelity, Final, Neumann

translation Marek Dyba