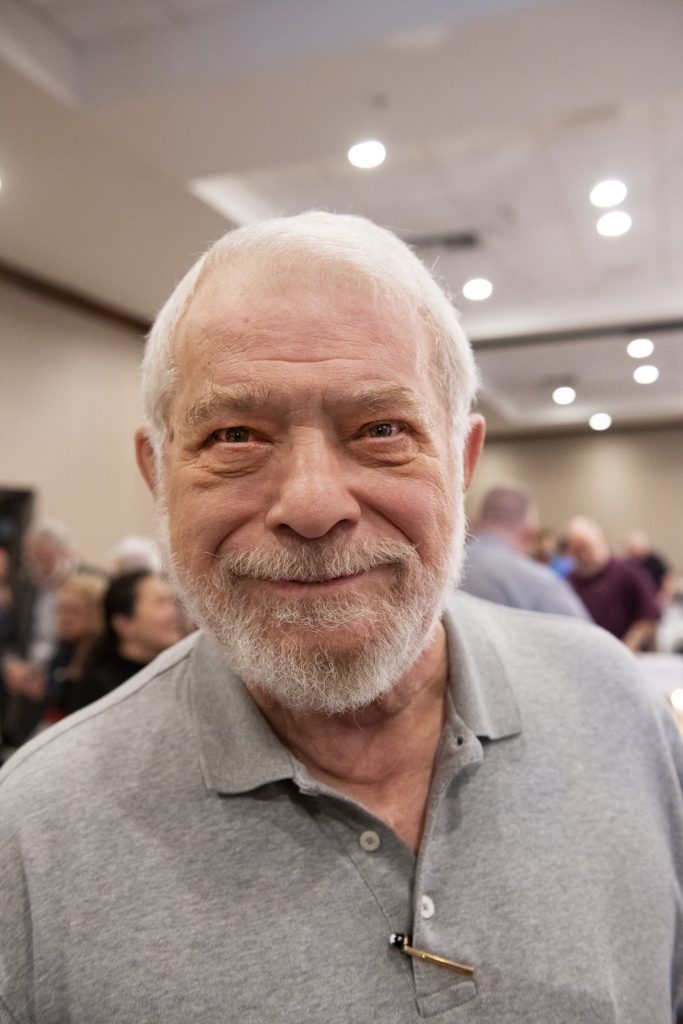

Roger Skoff explains…

We've all seen them: The LP turntable that's gold-plated, stands four feet tall, weighs hundreds of pounds, and costs as much as a small house before inflation set in. There's also the utterly gorgeous gold-plated or solid solid silver—meaning chassis, wiring, and even the wiring of the hand-wound transformers—electronics that have come out of Europe and Japan in recent times. Or the loudspeaker systems with unobtanium drivers, hand-blessed crossovers featuring exotic resistors and hand-rolled capacitors, and enclosures handcrafted from whatever material may be the most esoteric, expensive, or even, in accordance with Shinto beliefs, the most "spirited." (Including speaker horns machined from six-hundred-year-old cedar that might possibly—so it's implied—even be the homes of Hamadryads or Kodama [Japanese wood nymphs], which, unfortunately, have never yet been heard to sing along with the music.)

Another whole world of adventure is to be found in the sphere of High-End tube electronics. There, whichever tubes are the biggest, brightest, most oddly shaped or colored (consider the comforting green glow of the tubes made especially for just that one brand), or are hardest to come by, or most expensive to replace seem, just by virtue of their "wow" value, to have become the basis or the "secret ingredients" for a growing field of audiophile amplifiers—most of which seem to be stunning, at least in their purchase price.

It's easy to be attracted by the sheer bling of some of High-End audio's most expensive offerings but, at least for me, there are always the questions "What am I buying for all that money?", and "How much of what they're asking me to pay is for performance and how much just for the great looks?"

To answer those questions, two stories come to mind:

The first is where the title of this article came from. Many a long year ago, when I was just a young man, I and a friend were driving on Ventura Boulevard in California's San Fernando Valley. As we were about to pass it, my friend pointed out a sign on a roadside business that read: "Bar and Grill," and asked me what part of their business I thought the owners probably regarded as the most important.

When I told him that I had no clue—that, other than its sign, I knew nothing at all about the business or its owners—my friend corrected me, saying that the sign told us a number of things about the business, all of which, if we ever intended to go there, would certainly be worthwhile to know. One was the simple fact that the business was there. Another was that it served both food and drink. And the third and most important was that the business was primarily a bar, and only served food as something extra to bring in more customers and build its total revenue.

How did he know that? Actually, just a little thought about the sign made it obvious. First off, "Bar" was the first thing that it offered. (Think of the price-listing signs in front of gas stations: They always show the price of "Regular" first, because that's the fuel grade they sell the most of.) "Grill" was added to let customers know that they could order more than just drinks if they wanted to, but its second position on the sign reflected its second position in the business owners' minds. Also, the word "Grill" put it right on the sign that only one kind of cooking—the quick and easy sort of stuff that you can do on a grill—was available, and that there wasn't a full kitchen, as a sign offering "Fine Dining" might have indicated.

So, what does any of that that have to do with High-End HiFi? That's where the second story comes in.

I've told this one before, so you may remember it. Because it proves a point, though, please allow me to tell it again.

More than thirty years ago I bought a pair of solid-state amplifiers that, at $5500 each, were expensive for their time, but whose performance was so good that not only did I "have to" buy them, I still own, and regularly use them, even now. They were also physically gorgeous, done in what was called a "titanium" finish, with very thick machined aluminum faceplates and heavy, beautifully machined and finished front lifting handles to give them a look that was then, and still remains, truly elegant.

I liked the looks of those amps so much that one day, while I was talking with their designer (still one of the recognized "greats" of our industry, and still renowned for not only the sound but the unique visual appeal of his products), I complimented him on their great-looking faceplates and handles. His response was that it was a good thing that I and his other customers liked them, because that styling "package" had increased his cost of production so much that a full $1000 had had to be added to the retail price of each unit.

When I heard that, I was surprised, and asked why he didn't just leave off the fancy faceplate and handles and go with just simpler, cheaper sheet metal. "Wouldn't that let you drop the price to $4500 or thereabouts? And wouldn't that help you sell a lot more amplifiers?" I asked. "No." he said. "At $4500, but looking cheap, I might not have sold any amps at all."

And that, finally, gets to the point of this article: By its nature; by the amount of research that must go into developing it; by the quality of the materials and labor needed to produce it; and because it's never built in great enough quantity to allow for any significant economies of scale, good High-End audio gear has to be expensive. And because expensive gear won't sell unless it looks expensive, a significant amount of thought and expense has to go just into its appearance—which again increases its cost of production. And that's where the "Bar and Grill" thing comes in.

Bar and Grill owners can say, right out front, that they're there to serve drinks, and that whatever food they might serve isn't their place's main focus. And if the drinks and service are good and the people are congenial, they can get along just fine. Designers of High-End HiFi gear don't have that luxury: Because their products are expensive and have to look it, they can't just shrug the appearance factor off with a declaration that what they make is intended for listening and that its looks are of no interest to them. Great products—even great products at bargain prices—have done that and died.

Everything in High-End audio needs to look as good as it possibly can, and that has sometimes resulted in situations just exactly the opposite of what ought to be: There are now products on the market that seem to have gone so far in the pursuit of spectacular or exotic looks (and price tags) that they appear to have forgotten the goal of performance almost entirely, and simply become "luxury" goods.

Sometimes that can be successful: One "manufacturer" of CD players did virtually nothing, other than adding a classy name and a gold-trimmed faceplate to an ordinary (perfectly good-sounding) Phillips CD player and tripling its MSRP. Because the base product's sound was good enough for the needs and critical listening abilities of its buyers and because the price was still only a few hundred dollars, it was seen as a "bargain" luxury product instead of an overpriced cheap one, and people bought lots of them.

Perhaps it's not done quite as overtly as it was with that CD player, but there are still altogether too many instances where sellers charge a great deal of money for a good-looking product that delivers little more than just its good looks and "just good enough" performance.

That is not to accuse our industry or anyone in it of either "snake oil" or intentionally deceptive practices. The fact of it though, is that our is an "enthusiast" industry, where anyone who has the desire, the capital, and what seems to him to be a good idea, can start a business and offer what he thinks to be a worthwhile product for sale at any price level that he thinks the market might be willing to pay. (Just think, for example, how many "cottage" brands of cables and speakers there are, and how many variations have been offered of the basic Williamson tube amplifier). And think of what people are charging for them.)

Happily, there are other products out there too—a goodly number of them, if you look hard enough—that may not win any beauty contests, but that, for a fair or even bargain price, can provide far better sonics than you might imagine.

The way to find them is to, when you're shopping, ask those two questions that I mentioned earlier: "What am I buying for all that money?", and "How much of what they're asking me to pay is for performance and how much just for the great looks?"

Who knows, maybe you'll wind up with "gourmet" performance at a "bar and grill" price point.

Do it; shopping for new toys is fun, and finding them is the best fun of all....