The first fully functional HDD non-linear recording system, or how albums recorded using RADAR sound like

Digital Sound Recording – method of preserving sound in which audio signals are transformed into a series of pulses that correspond to patterns of binary digits (i.e., 0's and 1's) and are recorded as such on the surface of a magnetic tape or optical disc.

Looking at how people listen to music today, it's hard to comprehend how in a short time almost everything has changed in the industry. The way it is created, distributed, and reproduced has been revolutionized. Today, the vast majority of music resources are stored on HDDs, or SSDs, and the signal packed in WAV or FLAC files rushes through the highways of optical fibers, reaching smartphones.

Sometimes, but really rarely, if someone really cares about the full experience of the message in the recording, the music is played on specialized audio equipment, a file player or a computer connected to an external digital-to-analog converter. It won't be an exaggeration to say that sound eventually left the analog domain and hid in the bowels of computers saved as zeros and ones on mass storage drives. The few examples of analog recordings and analog carriers are not able to obscure this simple truth.

Ghost in the Shell

It is hard to dispute this state of things, because it is impossible considering the facts. It has been known for many years that HDDs and SSDs are an extremely unstable medium, and that some data is irretrievably lost after just one year. It is counteracted by installing matrices that duplicate information, preventing it from disappearing. However, this does not change the fact that—as it is estimated—every two years the contents of such a disk should be rewritten to a new one. However, as I say, it does not matter, because in this race of quality and durability versus convenience, the latter has won.

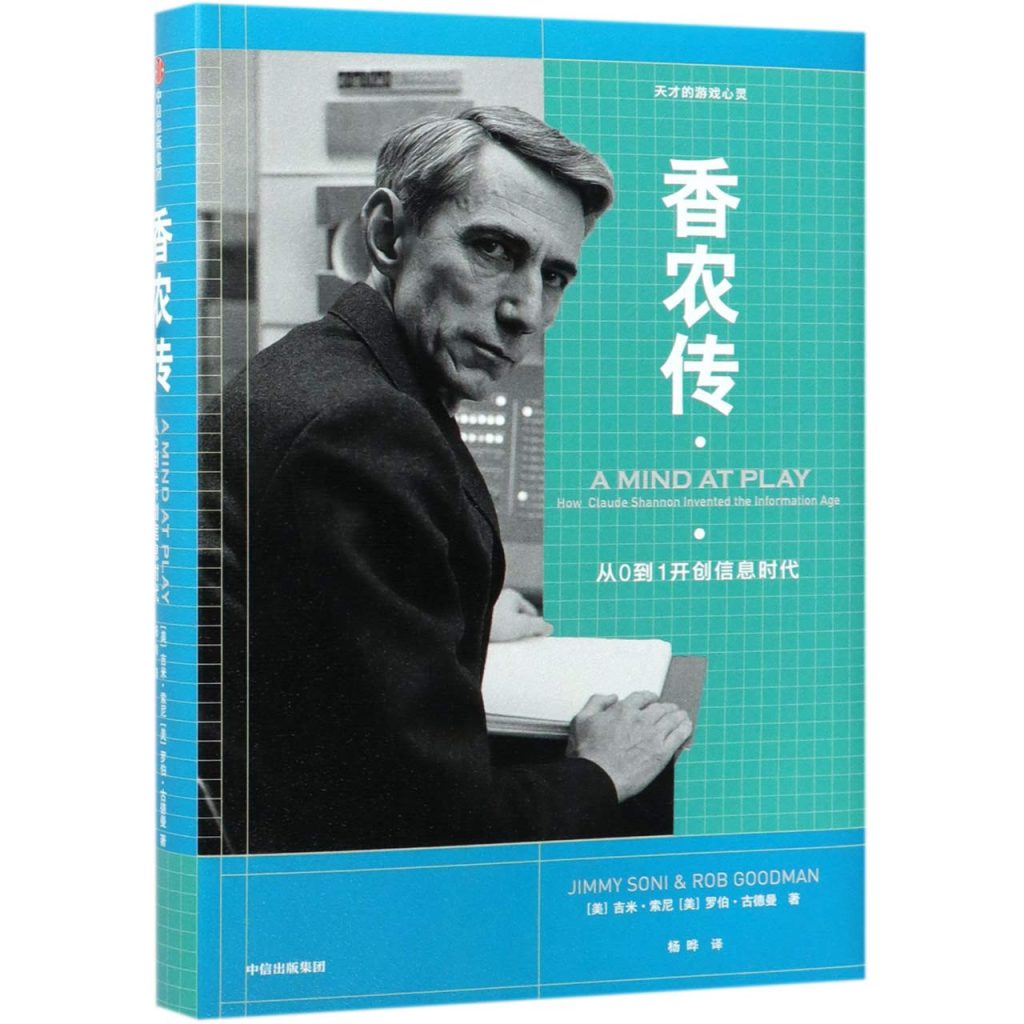

Claude Shannon's biography A Mind at Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age by Jimmie Soni and Rob Goodman, a Japanese edition (Simon & Schuster, 2017).

And yet, it was a dream of both computer scientists and a large number of musicians. The representative of the former should be Claude Shannon—scientist, mathematician of Bell Labs, author of the breakthrough work A Mathematical Theory of Communication. In 1943, the English mathematician and cryptologist Alan Turing, the father of cybernetics, visited Bell's laboratories, where he saw the young scientist and exchanged thoughts with him on—as James Gleick writes—"the future of thinking machines." Turing was indignant at the time when he heard Shannon's ideas, and he was most moved by futuristic plans for music.

Shannon wants to enter into the Brain [that is, into the computer] not only data, but also cultural stuff! […] He wants to upload music to it! Source: James Gleick, Informacja. Bit. Wszechświat. Rewolucja , translation: Grzegorz Siwek, Kraków 2012, p. 12).

In retrospect, Shannon's incredible insight and the surprising blindness of Turing, a genius after all, are surprising. However, many years passed before these dreams could come true and in this respect the British cryptologist, the father of artificial intelligence, was right—it was not easy.

In 1976 Xerox, then one of the leaders in scientific research, employing dozens of the best scientists and "producing" patent after patent, had something ready, which from some time later shook the foundations of the music world. Just before his European tour, the people of Xerox approached Herbie Hancock for help with a "project." Together with Bryan Bell, responsible for technical matters in the musician's band, they went to the Xerox PARC building in Stanford Research Park, where he had to sign a confidentiality clause for up to five years.

After passing the security gates and checking their passports, they were taken to the conference room where they were greeted by Alan Kay. As it turned out, Xerox developed what they called a "personal computer" called Dynabook. The computer was the size of a tablet and was the smallest of its kind. Its innovation consisted in the fact that, in parallel, elements that we now call "applications" were developed for it. Hancock was asked to rate the music app. In his autobiography, the pianist says:

Dynabook, a computer with a hard drive, could also record what I was playing and then play it back to me. I immediately realized that this device would change the way we create music forever. I'd never seen digital audio devices before, I only dealt with tapes. The idea that this little box could automatically remember and then immediately replay everything I "threw" into it was amazing.

I felt like I was listening to some science fiction story. Alan talked about portable devices, about batteries, about wireless connectivity, about more than sixty-four kilobytes of RAM. Source: Herbie Hancock, Lisa Dickey, Herbie Hancock. Autobiografia legendy jazzu, translation: Katarzyna Gawęska, Kraków 2015, p. 214.

To finish this story, let's add that in the 1980s Alan Kay started working with Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak for Apple, and that he is one of the fathers of modern computer science. The iPad, as you know it, is his work.

Towards HDD

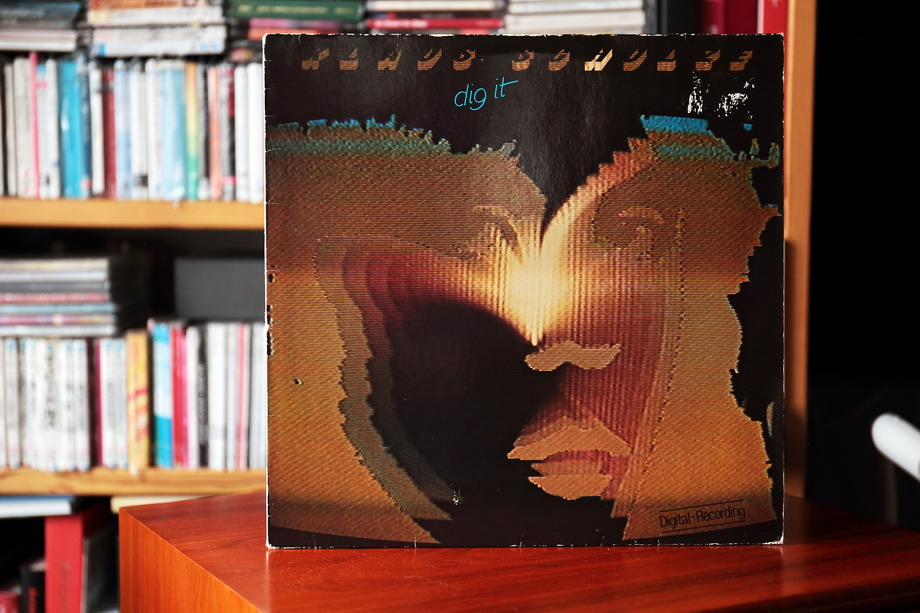

Recording music on HDD, however, had to wait until 1993, when the non-linear recording system RADAR—Random Access Digital Audio Recorder—was launched. Although in the late 1970s and early 1980s it was possible to record music digitally, but it was related to recording the sound of keyboard synthesizers. This is how, for example, the Klaus Shulze's Dig It was recorded, the cover of which reads: "All recordings by G.D.S. recording system at Klaus Schulze Studios."

Klaus Shulze, Dig It, Brain 0060.353, LP (1980)

In the first part of the article, we described the history of the RADAR system and showed the possibilities it opened up to record producers (HERE). In the second part, we went on to discuss examples of such recordings, focusing on albums released in the 1990s (HERE). We chose for the test following titles:

Blur, Blur, EMI Records, CD, 1997.

Bob Dylan, Time Out Of Mind, Columbia/Sony Records, CD, 1997.

Blondie, No Exit, Beyond/BMG Japan, CD, 1999.

This time we will check out another three albums released in the 2000s.:

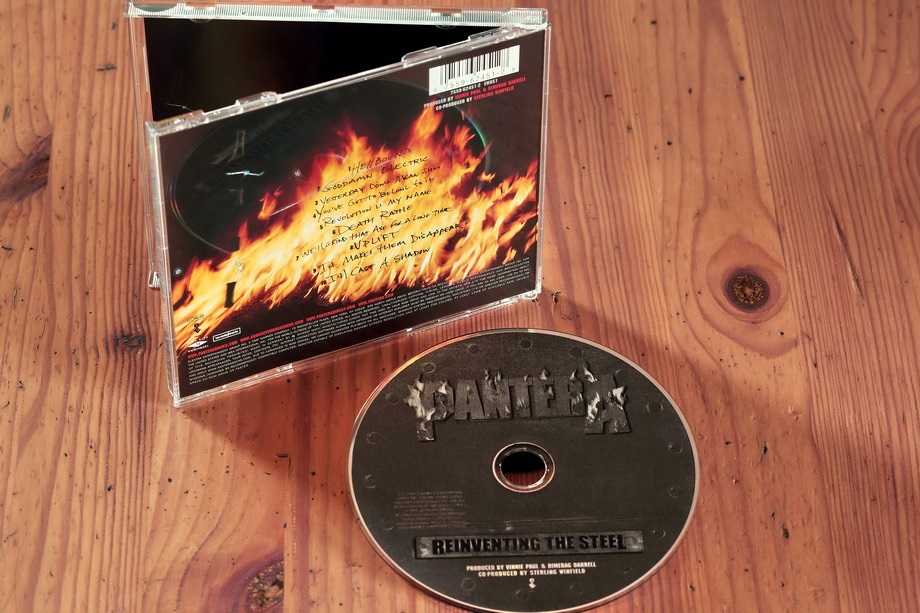

Pantera, Reinventing The Steel, EastWest Records America, CD, 2000.

U2, No Line On The Horizon, Island Records/Mercury Music Group (Japan), CD, 2009.

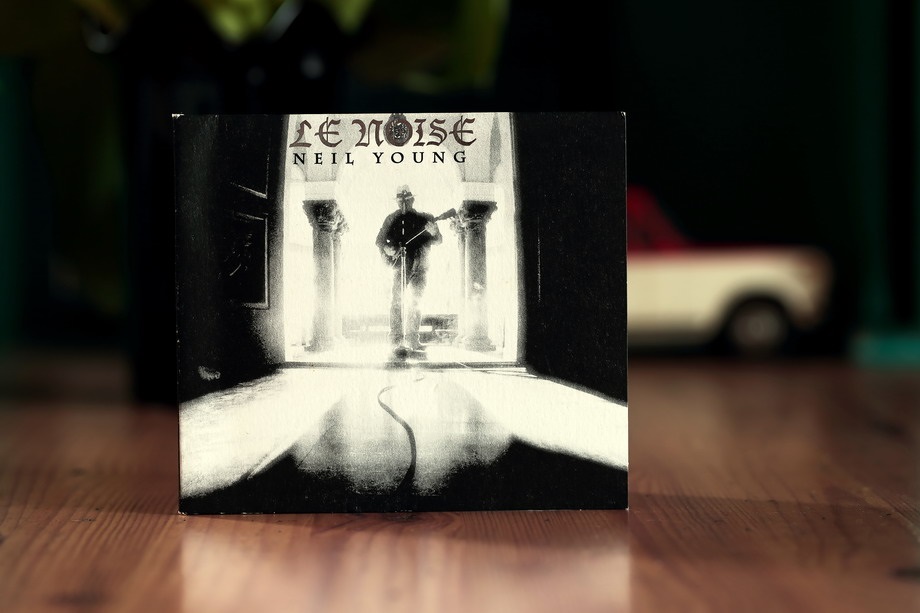

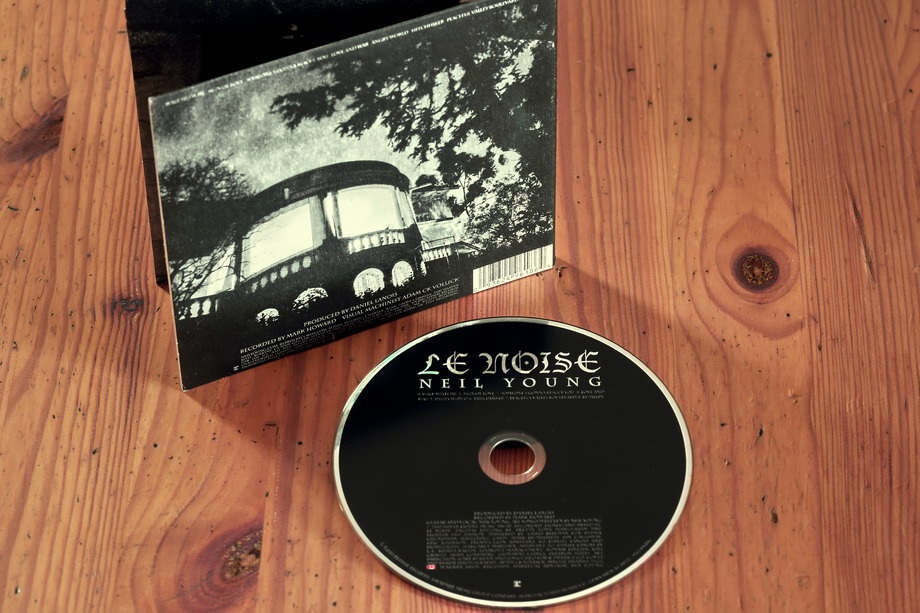

Neil Young, Le Noise, Reprise Records, CD, 2010.

As in the case of ADAT tape recorders, and previously all digital recorders, the recorders had a choice of several options regarding the method of Recording, Mixing, Mastering. Unlike in the "analog" era, we don't know too many details about the recording and mixing sessions. The most important source of information of this type has also disappeared, because the 1990s was a period in which Billboard magazine stopped informing about the methods of recording specific titles. However, we will try to reconstruct the most likely scenario, presenting it as:

Digital (RADAR), Analog, Digital (stereo, RADAR, DAT?)

Listening: Pantera, Reinventing The Steel

Pantera is the name of an American band performing a variety of heavy metal known as thrash metal, we also owe them popularization of its groove metal variety. It is associated with the so-called second wave of thrash metal together with the bands such as Testament, Sepultura, and Machine Head. Formed in Texas in 1981, it is known for its line-up starring the Abbott brothers, drummer Vinnie Paul and guitarist Darrell Lance, accompanied by vocalist Phil Aanselmo and bassist Rex Brown.

The band released their debut, Metal Magic, in 1983 thanks to the Abbott's father, a country music producer. After the release of their third album, the band changed their style by taking Phil Anselmo on board. The music got heavier, denser and it is referred to as a mix of glam and trash metal. In 1989, Darrell Lance joined the Megadeth band, which meant that the brothers devoted less time to their own band.

The most important album is Vulgar Display of Power, released on February 25, 1992, on which the band developed their "groove" style. After Anselmo overdosed on heroin in 1996, the band came back to working with him on the Reinventing the Steel, which turned out to be their last album. The Panther was officially disbanded in 2003. They have sold over 20 million records and received four Grammy nominations.

Recording

Released on March 14, 2000, Reinventing the Steel is the ninth and last official album of Pantera. In "Goddamn Electric" we will hear the guitar of Kerry King, the guitarist of the Slayer. To date, the album has sold over 600,000 copies.

The album was produced by the Abbott brothers—Dimebag Darrell and Vinnie Paul. The man behind the recording was Pantera's longtime collaborator, Sterling Winfield, a technician dealing with their bass guitars, and Vinnie Paul, who also prepared the mix and helped him. Howie Weinberg took care of mastering. In the so-called credits, also Roger Lian is mentioned, who edited and sequenced the material.

The band realized two projects simultaneously—the album we are talking about and, with David Allen Coe, Rebel Meets Rebel. As we read in the Guitar World magazine, "ready to experiment, they chose their own studio without the usual accompanying people as the place of recording, inviting Winfield to produce it." Sterling Winfield is currently working at his Boot Hill studio in Corinth, Texas. His portfolio includes artists such as Hellyeah, Damageplan, Hatebreed, King Diamond, Mercyful Fate, A Rebel Few, Texas Hippie Coalition, Vangough and—interesting fact—Erykah Badu.

The band then decided that they wanted to give the material a more "old school" feel. Winfield says about it like this:

They wrote and recorded exactly what they needed for an album. All unnecessary allowances were cut off, there was no extra material or extra approaches. Therefore, there is no unreleased bonus material in the reissue. Alison Richter, Producer Sterling Winfield on the making of Pantera's final album, Reinventing the Steel, www.guitarworld.com

To achieve that, they used the old analog MCI 500 console (MCI was bought by Sony), dating back to the 1970s, but with the old microphone preamplifiers replaced. These were put together in a small box by the band's friend, Jason Chamley, who Wienfield called "the genius of electronics." It is because of him that the studio where the album was made was called Chasin' Jason.

The recordings were a hybrid. Part of the material was recorded on 2-inch analog tape, and then recorded on Otari RADAR, to which the rest of the tracks were added. It was important for the band not to even "touch" the DAW (digital audio workstations) and WAV files while recording. The material seems to have been mixed in the same place with the same mixing console that was used for the recordings.

We mentioned Kerry King at the beginning—a curiosity about him is that he recorded his ending solo for the "Goddamn Electric" in a bathroom. It took place after the Slayer concert at Ozzfest in Dallas. Wienfield brought a Tascam DA88 and a Shure SM-58 microphone with him, and the guitarist added his solo to the raw stereo mix and returned to the stage.

Analog/Digital (multi-track RADAR), Analog, Digital (stereo, RADAR, DAT?)

The Reinventing the Steel originally was released only on CD and cassette. In 2012, a remaster was made and the material was released on an LP. The next remaster is from 2020. Celebrating the 20th anniversary of its release, on January 8, 2021, Rhino Records released a limited, three-CD edition of the album with re-mixed and partially changed material. The WAV 24/96 files as well as a triple (USA) and double (Europe) album with additional songs were released on the market. A year later, the LP version with the same remaster hit the market.

Sound

"Heavy" music is not associated with high-quality sound. It is no different with the Reinventing The Steel album. It has a narrow perspective and is massacred by compression. The drums sound like Vinnie Paul is playing cereal boxes, and the guitars sound quite screeching. But guess what? If you listen to such music, it makes sense. Pantera's music is about energy, anger, "power." And this is exactly what we get on the album in question. The fact that the band was sitting relaxed in the studio instead of going to Dallas to record really paid off.

The recording has a very good clarity, which is always difficult in metal genre, and the sound is not too bright. It is obvious that Phil Anselmo's vocal is set quite high, that it is compressed and has a small volume, that's all clear. And yet we are dealing with a sound that supports the music, not interferes with it. It seems that a good use has been made of the purity of the digital medium, such as the RADAR recorder, without going to the wrong side of brightness. It's good, strong performance within a metal idiom that has benefited from the technological advances in recording technique.

Listening: U2 No Line On The Horizon

No matter what we say about U2, it will be too little for their fans, too little, and totally wrong. When you deal with such a highly acclaimed, successful band that has had such an impact on rock music, that has been active for so long, which has sold over 150 million albums, has 16,839,117 likes on Facebook and 17,396,388 listeners (monthly) on Spotify, there is no other way, you'll never truly satisfy the fans. Nevertheless, let us present some of the most important facts about their career.

U2 – picture on the back of the No Line On The Horizon cover, photo: Antony Corbijn/press release Mercury Music Group

U2 is an Irish band, founded in Dublin in 1976. From the very beginning its members haven't changed: Bono, as a vocalist and rhythm guitarist, the Edge playing the guitar and keyboards, bassist Adam Clayton, and drummer Larry Mullen Jr. They started out as a post-punk band with the Boy (1980) album, which together with the next one, War from 1983, established their status as a socially and politically engaged band. However, it was their fifth album, The Joshua Tree from 1985, that made them a superstar.

Recorded at Hansa Studios in Berlin and released in 1991, Achtung Baby showed a new face of the band with music, in which critics heard alternative rock, industrial music and even dance music. It is the group's best-selling album, with 18 million copies sold. Subsequent albums were received with mixed feelings and it was only the All That You Can't Leave Behind from 2000, that had taken a long time to record, that allowed them to get back into fans' grace.

Recording

Recordings for U2's twelfth album No Line on the Horizon began in 2006, and Rick Rubin was chosen as its producer, we wrote about him on the occasion of Johnny Cash's My Mother's Hymn Book (2004). Sessions were quickly suspended, however, and the material recorded at that time was archived. The work was resumed a year later, but the producers were already Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois.

Recordings started in Fez, Morocco in May 2006, at Riad El Yacout, and subsequent sessions took place at Hanover Quay Studios (Dublin), Platinum Sound Recording Studios in New York, Edge's French studio, and London's Olympic Studios, famous for albums recorded there by Hendrix, The Who, Madonna, and Adele. The Moroccan sessions took place in the courtyard of a hotel rented at that time.

U2 in Olympic Studios, in London, while working on the No Line On The Horizon photo Kevin Davies

The main recorder was a 24-bit RADAR, which was no surprise. As we wrote on the occasion of the Bob Dylan'S Time Out Of Mind (1997), recorded using the same system, having his studio in Canada, the country where RADAR was developed, Lanois was involved in this first non-linear writing system from beginning. And only part of the session, like the one at Edge's house, was created on a computer with Pro Tools, using the Neve console.

Declan Gaffney, sound engineer responsible for the most of the material said:

The main thing about working with RADAR is that you can very quickly move from one song to the next. When U2 have put down an idea they'll come up with new ideas during the next playback and will just pick up a microphone and start singing or playing guitar, and with RADAR you can drop these things in on the fly, without stopping. I couldn't imagine doing a writing session with these guys using Pro Tools, because you simply don't have time to create three new tracks and put them in record. That new guitar or drum part could have vanished into thin air by then. Paul Tingen, Secrets Of The Mix Engineers: Declan Gaffney, www.soundonsound.com

We don't have much information about the mixing process, but almost certainly the sound was recorded using an analogue mixing console. The mixes were hybrid, some analog (at Platinum Studios it was the SSL K series console), some "in-the-box," that is, in Pro Tools.

It is known, however, that as a result of many spontaneous sessions, so much of material was created, that nobody was able to make any sense of it anymore. The scarce information also shows that also the recording was a hybrid process, although the material was recorded in the RADAR system, its editing and processing took place in the Pro Tools DAW station. The album was mastered at Mastering Studios in Chicago by John Davis. Supposedly as many as 20 people involved in these two years of recording, mixing, re-recording and re-mixing and editing.

The album, initially planned as two EPs, was released in February 2007 as a full-length album. The music on it was more experimental than on the previous albums. However, sales of 5 million copies were disappointing for the band (!).

Digital (multi-track RADAR), Analog, Digital (stereo, RADAR, DAT?)

Releases. No Line on the Horizon exists in many versions, the main difference being the way it was packaged. The album was released on a CD and a double LP, the digital version had releases in various countries. Part of the edition was released in a box with a DVD, and another part with additional printed materials.

In 2014, the material was re-mastered and the machine started working again. It is worth noting that the SHM-CD version was released in Japan, and the LP was released on transparent vinyl. We are reviewing the first Japanese release from 2009.

Sound

We have been used already to the fact that the U2 albums sound quite "high," it is no different here as well. From the first lines, sung by Bono in the title track "No Line on the Horizon," we hear this signature. The upper midrange is "extended," and the vocal has a strong compression, which places it quite close to us, despite the fact that it has a lot of reverb.

The perspective of the album is rather shallow, although when producers use the effects creatively, as in the second track on this album, "Magnificent," the sounds come from the side and back for a while. But only at the beginning, because everything soon returns to "normal." And the norm for this album is compressed, slightly hollow sound with small phantom images and a shallow stage. It is also problematic to shape the timbre in which the upper midrange is dominant and there is no saturation, not to mention the bass.

Perhaps it was about simulating the use of an analog tape, with its strong saturation. Same happens with Bono's vocals, who seems to almost swallow the mesh of the microphone, making it sound as if he is standing on the stadium stage. So perhaps the idea was to achieve such a rather dirty and "raw" sound—I don't know. I do know that it doesn't sound very good

Neil Young, Le Noise

Music

Canadian-American folk and folk-rock singer, songwriter, and music writer Neil Percival Young was born on November 12, 1945 in Toronto. In the 1960s, he moved to Los Angeles, where he performed with the Buffalo Springfield band. Since the beginning of his solo career, that is since 1969, he has been recording with the band called Crazy Horse, with which he recorded his most famous albums, including the Harvest from 1972. Throughout his career, Elliot Roberts was his manager at Reprise Records, whom he shared with Joni Mitchell.

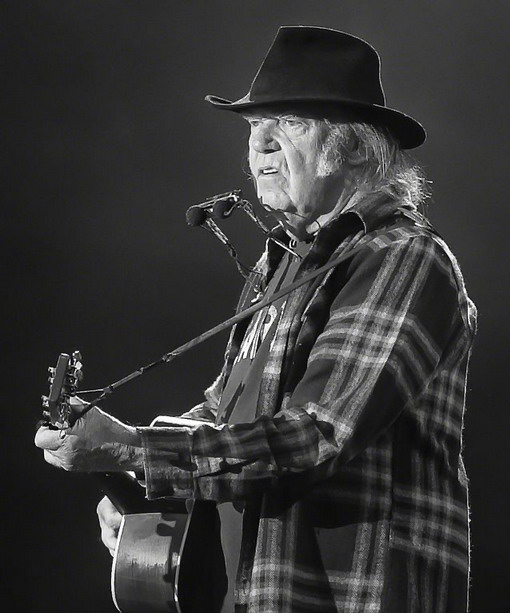

Neil Young on the main stage of the Stavernfestivalen in Norway July 07th 2016 photo Tore Sætre/wikipedia CC

A long career means the possibility to collaborate with many artists. And this is the case of Young. He played in Crosby, Stills, and Nash, with Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, and The Band. Linda Ronstadt and Emmylou Harris made appearances on his records as well. The 1980s are considered the time of "experiments" in his career. At that time, albums were created using electronic instruments, including a vocoder, synthesizers, and electronic percussion. In the following years, he returned to neo-folk and proposed different music.

In May 2010, the singer's friend David Crosby revealed that Young is working on a new album with producer Daniel Lanois. As he said, "it will be an album straight from the heart" and that it would be, in his opinion, "a unique album."

Recording

Released September 28, 2010 Le Noise is Neil Young's 30th studio album. It was recorded entirely in one location, in the Le Noise studio in Los Angeles, and was produced by Daniel Lanois. The title of the album: Lanois = La Noise, was taken from the name of the producer's home studio where the album was recorded.

Three the same mixing consoles Neve BCM10, that were to be used for the recording session in the Le Noise (Silverlake) photo: Daniel Lanois

Young called Lanois in early 2010 with an idea for an all-acoustic album. The producer picked up on the idea, but the concept changed during the development of the first song "Hitchhiker," written in the 1970s. Young decided then that an electric guitar would suit him better, and so almost the entire album, except for two acoustic songs, was recorded.

However, the guitar sound is unique on this album. The musician got it by playing a Gretsch White Falcon with a stereo pickup connected to two Fender Deluxe amplifiers, and the whole thing was processed in the sub-harmonic sound generator Eventide H3500. During the recording, two effects were applied live: Lexicon Prime Time and TC Electronics Fireworks.

The producer of the recordings was Mark Howard, said in an interview for the Sound on Sound magazine:

Another reason for using the Radar is that I don't like the sound of Pro Tools, and I also don't think it's a reliable platform: it crashes too often. You also end up doing things inside of it with plug‑ins, and you end up dealing with the issue of latency. Plus people using Pro Tools are listening with their eyes instead of their ears. I like the Radar because I grew up using tape recorders, and it is like using a tape recorder. You record something, you play it back.

You don't have to think about anything else, or spend hours studying how to use the software or get something to work again when it crashes or doesn't open. With the Radar, you can spend these hours on dealing with the music. Recording with Radar is much quicker than with tape or Pro Tools. Rewind and playback is instantaneous, and you don't have to constantly wait for things to load, unlike with Pro Tools. It's such a frustrating tool for me. If I ever have to use it, I get a guy to do it for me, so I don't have to look at it."

Paul Tingen, Daniel Lanois & Mark Howard: Recording Neil Young's Le Noise, www.SOUNDONSOUND.com

The album was recorded almost completely live, but in an unusual way. The recording was made in three different rooms. In order not to run around with the recording system every time, the RADAR and three of the same Neve BCM10 mixing consoles—one per room—were set up in the hallway. Ultimately, however, it turned out that most of the material was recorded using one console - Neve Melbourne.

Howard recalls that he was listening with a pair of Tannoy Gold speakers featuring 15-inch woofers, supported by four (!) Clair Brothers stage subwoofers, each with an 18" driver. At the rear he placed a couple of Klipsch speakers. As he says, he conducted the auditions at "full volume," and "when you put your hand on the wall you felt that everything was shaking".

Lanois and Howard recorded Young in an extremely minimalist way, using the 24-track version of the iZ RADAR 24 (24-bit) system and the GP2 BL990 mic preamps made with Mark Howard and Brother Bob. As he says, he does not use tone controls or compressors. He only introduces corrections during the mix, on the digital Midas 4000 console. Mastering was done by CHRIS BELLMAN in Bern Grundman Mastering.

Digital (multi-track RADAR), Digital, Ditital (stereo, RADAR, DAT?)

Releases: Le Noise was released on CD, LP, as well as AIFF (24-bit), AAC and mp3 files. In the "deluxe" version, the album was available together with a DVD, on which you could see Young while recording the music. There have been no re-issues, apart from the unofficial 2013 release.

SOUND

Right from the first sounds of Le Noise the power of the presentation is surprising. Young's vocals are cut back and you can hear that it was recorded with a dynamic microphone (Shure SM58 Beta). They sound more blunt than capacitive microphones, and are often used to help control a singer's speech problems or produce other effects. It was, I think, about matching the vocal sound to the guitar sound. This is why the voice is positioned far behind the line connecting the speakers, and in addition to that on a long reverb. But not always—already in the second track, "Sign Of Love," the voice was processed in such a way that it comes from the sides. This is done using phase reversal effects.

But let's get back to the guitar. The first track was very powerful because an incredible bass was generated from this instrument—it will be a challenge for any system. The second track shows the guitars in a more classic way, but only in "Someone's Gonna Rescue You," the third track of this set, you can hear the natural sound of the guitar more clearly. Here, too, the sound is distributed in the channels, but you can already hear what instrument we deal with.

Until in the song "Love And War" we hear a pure acoustic guitar and vocal, in which the only effect, apart from a short reverb, which introduces the ping-pong effect that was used, seems to be phasing. We have a short delay applied to the guitar, which can be heard as the sound repeats when it decays—Howard mentions that he did not use any reverb during the recording.

And so you can enjoy every track—each subsequent piece is an exercise in the imagination. This is based on adding different types of effects to the guitar, multiplying it, etc. The same happens with the vocal—sometimes it is close to us, sometimes further away, sometimes it is more processed, sometimes less so. If I read something like that, I would be almost sure that it the sound was terrible—and it wasn't, it was just different, completely different.

The sound of this album is incredibly coherent and dense. Its timbre is embedded in the lower midrange, which gives the impression of fullness and saturation. The panorama has an extremely wide stereo base and an excellent depth. I talked about various ways of using the effect on a vocal track—this is a test of system differentiation. Le Noise is a great release offering brilliant music and sound.

A short career of RADAR

Released in 2010, the Le Noise was a death-knell for the RADAR system. Even then, it was already an anachronism, just like analog tape recorders before. The digital technique appeared in the recording industry in the 1970s, but it was not until the 1980s and 1990s that it was accepted by major recording studios. However, the transition from analog tape to digital tape and then to a hard drive was not a smooth and hassle-free process. Older and newer systems functioned side by side, and their use was usually determined by habit and the so-called "workflow" of producers and recording engineers, and sometimes also musicians.

Cited by Samantha Bennett Stephen Street, responsible for the sound of, for example, Blur's Parklife album said:

Once you get used to a system, you'll always have a hard time adjusting to something else. So when Pro Tools came out, I didn't like it because it was too different for me from what I got used to when working on C-Lab. In my opinion, if you feel comfortable with something, try to be good at it instead of trying to change too many things.

Samantha Bennett, Modern Records, Maverick Methods, p. 128.

However, the "new" was already there and was getting ready for an absolute victory. From the mid-1980s, the platform on which many sound engineers worked was the Apple computer. In 1987, the Mcintosh II model was presented, which was a breakthrough for the industry. Soon before, in 1984, the American company Digidesign presented a program called Digidrums, the version of which from 1989 was already called Sound Designer, and which became the basis of work for many producers and sound engineers, as well as musicians who wanted to modify recordings in the easiest but also deep way.

That same year, Digidesign also introduced Sound Tools, an early version of Pro Tools. In this way, the computer became a "workstation" - a DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) on which it was possible to record, edit, and later also mix and master music recordings without leaving the computer environment. Thanks to the opportunities they offered and the low price, DAWs from various companies revolutionized the music industry very quickly. In 1992, over 3000 Pro Tools systems were in operation all over the world. Soon after, with the v5 version, recordings made with it entered the charts to dominate them in a short time. Today, albums are almost exclusively recorded this way: we live in the world of Pro Tools, for good (sometimes) and for bad (usually).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Entry: Pantera, in: wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org, accessed:: 30.11.2021.

Entry: U2, in: wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org, accessed:: 30.11.2021.

Entry: Neil Young, in: wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org, accessed:: 30.11.2021.

Entry: Le Noise, in: wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org, accessed:: 30.11.2021.

5 Things You Didn't Know About Pantera's 'Reinventing the Steel', www.revolvermag.com March 21st 2018; accessed:: 30.11.2021.

Alison Richter, Producer Sterling Winfield on the making of Pantera's final album, Reinventing the Steel, www.guitarworld.com Aug. 15th 2020; accessed:: 30.11.2021.

Chris Krovatin, 10 Famous Albums Where Everything Was Crazy Behind The Scenes, www.kerrang.com; accessed:: 30.11.2021.

Tonymusic.org; accessed:: 3.11.2021.

Paul Tingen, Secrets Of The Mix Engineers: Declan Gaffney, Sound on Sound June 2009, www.soundonsound.com; accessed:: 3.11.2021.

Stephen Pate, Daniel Lanois dislikes the sound of Pro Tools DAW, njnetwork.com Feb. 22nd 2011; accessed:: 3.11.2021.

Bob Boilen, First Listen: Neil Young, 'Le Noise', choice.NPR.org

Paul Tingen, Daniel Lanois & Mark Howard: Recording Neil Young's Le Noise, Sound on Sound Feb. 2011, www.soundonsound.com; accessed:: 30.11.2021.

Brandy Lewis, Neil Young and Daniel Lanois clickon ‘Le Noise', Los Angeles Times Sept. 19th 2010, www.latimes.com; accessed:: 30.11.2021.

Howard Massey, Behind The Glass Volume II. Top record Producers Tell How They Craft The Hits, Backbeat Books, San Francisco 2009.

Samantha Bennett, Modern Records, Maverick Methods. Technology and Process in Popular Music Record Production 1978-2000, Bloomsbury Academic, London-New York 2019.