Roger Skoff writes about audiophiles and double-blind testing.

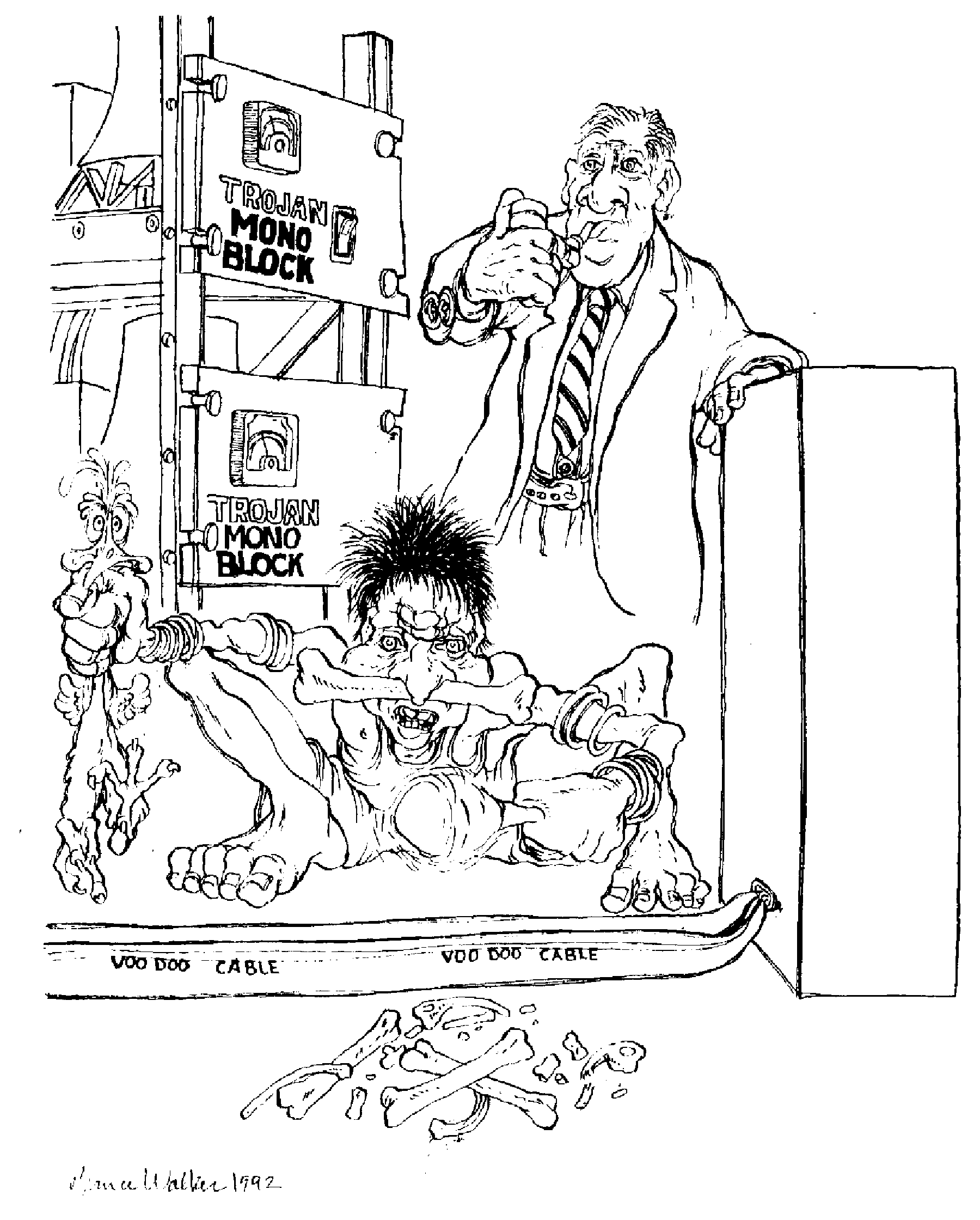

Yup, I was on Facebook, browsing one of the audiophile groups (you'll probably know which one from what I'm about to tell you) when I came across a slugfest between a long-time reviewer friend of mine and several "rationalist" "audiophiles" (Yeah, both of those terms are in quotes because I find both of them doubtful, at best). Somebody had written in to ask if a certain kind of cable (GOKK! Horrors!) actually made any real sonic difference. My reviewer pal responded that the proper way to find out was to listen to some cables and see for himself, whereupon; another guy leaped in to say that double-blind testing is the only way to get real information, and another guy said "yeah!" and somebody else said "No!' and the fight was on. Again. For the however many-eth time.

In case you somehow don't already know what "double-blind" testing is, here's the scoop. For comparative testing purposes, there are three basic kinds of approaches that may be taken: "Open," "Blind," and "Double-Blind."

An "Open" test is one where everybody (both the tester and the testee(s)) knows what-all is being tested and which one of a compared set of things is being tested at any given time. Because that's known to both the tester and the testee, it's possible that one or the other could cheat or pick a favorite and thus bias the outcome of the test. The open test format is therefore generally accepted as the least reliable for turning up "good" information.

In a "Blind" (also called "Single-Blind") test, while the tester knows both the things being compared and which one of those the testee is experiencing at any given time, the testee is, at most, only allowed to know what the options are, but is never, during the term of the test, allowed to learn which one he is actually being subjected to. This reduces the possibility of either "placebo effect" or a conscious bias on the part of the testee, but knowledge of what's being tested may still bias the tester, so this type of testing, while less subject to error than the Open test format, is still regarded as not entirely reliable.

The third type is the "Double-Blind" test, where, although both may know what things are being compared, neither the tester nor the testee is allowed to know which of the compared set is currently under test. For scientific and certain other purposes, this make double-blind testing the "Gold Standard"—the one which, because it is the least subject to either conscious or unconscious bias, is the most likely to produce reliable results.

That's why virtually all medical testing—as for the current development of a vaccine for COVID 19, for example—is done double-blind, with two test groups; one given the subject vaccine; the other given a placebo, and neither the test subjects nor the testers knowing, until after the test is over and the results have been tabulated, which group got which.

Now, before I go any further, let me say that I agree with the advocates of double-blind testing. Where it is applicable, it is definitely the best method for comparative testing yet devised! The problem with double-blind testing is that it's not applicable to either music or to music listeners.

For double-blind testing to work, there must be only one tested variable. In the COVID-19 case, for example, that variable was the presence or absence of an actual vaccine. (As evidenced by the health outcomes of the two groups; one getting it and one not getting it) This "one variable" requirement is absolutely essential for valid comparative testing because any more than one variable will allow for uncertainty about the cause for whatever different results may be reported, and the more variables there are, the less certain the cause will become.

For the testing of just sound or the electronic signals that go to produce it, it is possible to isolate one single factor for testing. That might be anything from—as with the vaccine—the simple presence or absence of signal ("Is there any signal there?"), to amplitude ("Which is louder, tone A, or tone B?"), to frequency ("Are these two frequencies the same or different?"), to duration ("Which tone lasts longer?"), or to any other of a broad range of perceivable and isolatable things, none of which is by itself, as you can easily understand, of any significance whatsoever in trying to choose or evaluate hi-fi gear.

Truly, who really cares about any of those things except in a musical context?

When music is the "test signal", however, there's never just one single variable to test. Music always has more than just a single characteristic present at any given instant, and changes from instant to instant over any piece of music and over any length of time.

Some of these changing characteristics include frequency content (the frequencies, from lowest to highest, that are actually present at any given moment), amplitude (overall and relative at the present instant), harmonic structure, dynamic range (the difference between the loudest and the quietest tones possible and present), transient attack and decay, and many more—just in the music, itself. Then, when the recording and playback process is considered and, unless headphones are used, the acoustics of the listening room, the positions of the speakers within it, and the position(s) of the listener (or each listener) relative to the speakers are added, the potential number of variables possible at any given instant may range into the hundreds, or even more.

And there are at least three more factors that must be considered: Listener bias, musical content, and listener attention span.

The fact of it is that different people listen for different things, depending on their own personal tastes and preferences. For me, personally, the first things to catch my ear are imaging and soundstaging, and then all of the other sonic characteristics follow, in declining order of my interest-in or response-to them. With other people, it's much the same thing, but perhaps in some different order. One of my HiFi buddies is an absolute freak for transient attack and decay. Others are bass fans, or listen first for "clarity," or "harmonic envelope," or "believability" (how do you quantify that?), or whatever else turns them on. According to one psychologist friend of mine, (who, incidentally, used to be a reviewer for TAS) many women don't pay much attention to the sound at all—the first thing they listen to on any song is the words!

In short, when a piece of music is playing or is the subject matter for a test—regardless of whether open, single-blind, or double-blind—the testee may all be listening to the same thing, but what they actually hear may be significantly different!

Of equal importance with listener bias is the matter of musical content. The easy stuff—the stuff that can be meaningfully tested by a double-blind protocol— is all distinguished by one common characteristic: every moment of it contains all of the points of information possible. The test material will always be of the same frequency or frequencies; always be either present or absent; and always be at the same amplitude and every other definable characteristic, regardless of whether the test is a minute, an hour, or several days long.

Music, however, unlike any signal suitable for double-blind testing, is constantly changing. At any moment its frequency content can (and likely will) change to include anything from a single tone and its harmonics to virtually any combination of sounds imaginable. Its amplitude, too, is constantly changing; ranging from the total silence between the notes and phrases of virtually any musical score, all the way up to the full orchestral and double-choral tutti of Mahler's Symphony #8. (Symphony of a Thousand) HERE. And that's just considering total amplitude, without any regard for the volume relationships of different sounds or instruments within the musical construct.

What this means is that, when music is used as a test signal, not all of the information possible will always be there to be listened to and made part of the comparison process, and that, therefore, at any given moment some element(s) necessary to a fully correct judgment will almost certainly be lacking.

When this is added to listener bias toward certain musical characteristics and away from others, the combination has to cast serious doubts on any double-blind testing of musical material: One can never be certain that any particular bit of potentially significant information will be included in the test sample. And, even if it is, one can never be certain that a listener will be focused on it...or even hear it at all.

When, finally, listener attention span is brought into the mix, and we consider that, even when we're doing serious and concentrated listening, our mind may still momentarily wander from the music at hand to something else, is it any wonder that the results of double-blind testing of audio products conducted with a music signal have tended to show no significant differences?

It may be because a particular piece of gear has its greatest strength or weakness in one particular performance area and that particular performance area isn't included in the portion or kind of music presented during the test. (There are no drums in a string quartet) Or maybe it was there, but it's not the kind of thing we listen for. Or maybe it was there and the kind of thing that we listen for, but at the moment that the music presented it, we were "wool-gathering" and simply not listening. Either way, we're not going to hear the difference and, in all honesty—even to ourselves—we will believe and declare that none exists.

What I've just written is not new. I and others have written about it before, and genuine scientists know that it is true. Even so, in the name of "Science" audiophiles and amateurs will continue to seek their "Gold Standard" in a test protocol that must either, when it is confined to a single test variable (an unchanging test tone), as is required, produces results that are of no interest or significance, or that, when a music signal is used, produces results that can never be relied upon.

It's happened again, and it apparently will continue to happen until audiophiles actually learn to use and rely on their own ears instead of somebody else's test results.

Our ears are the real and only "Gold Standard!"