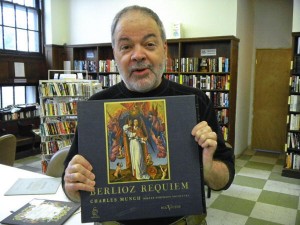

Harry Pearson, a characteristic pose. RMAF 2009, Denver, CO

With the death of Harry Pearson, Michael Mercer and I talked and decided that we would put our thoughts about his passing together in a pair of brief reflections, and publish them together. Others have already done so, and will probably continue to do so, at least, for a while. It's how writers deal with things. As you'll see, Michael's perspective is close-in, tight, and breathes the daily presence of the man as he knew him and came to understand him. For Michael, Harry was an editor, a mentor, a friend, a beloved tormenter, a jester, and a disciplinarian. His presence towered over Michael when he was young, and left a lasting imprint on his entire life thereafter, long after he had departed from TAS, and TAS departed from Harry.

In fact, Harry Pearson died on the day that Michael Mercer turned 40.

Timing. Harry had that.

Michael will be shoveling the aftermath and debris of this event for all of the rest of his future birthdays, I reckon. Some influences are inescapable; you don't lose them, you just live with them. Michael writes from the heart; you can mine his wordsmithing elsewhere in this issue.

My perspective is very different, as you'll see…from a distance, and without any of the sense of awe or extraordinary influence that others have mentioned. It is here as a counterbalance to Michael's outlook. Both are pieces of the puzzle that Harry Pearson was, views through different prisms, but neither are the "Rosebud" of his story. As with Charles Foster Kane (an allusion that Harry would appreciate deeply, I am quite sure), I don't think that anyone knows what key might unlock Pearson's life…perhaps there is none.

You can stop here, and go read Michael's very personal picture, and then return here, or you can stay here with my account, and then go on to his.

Either way, read on….

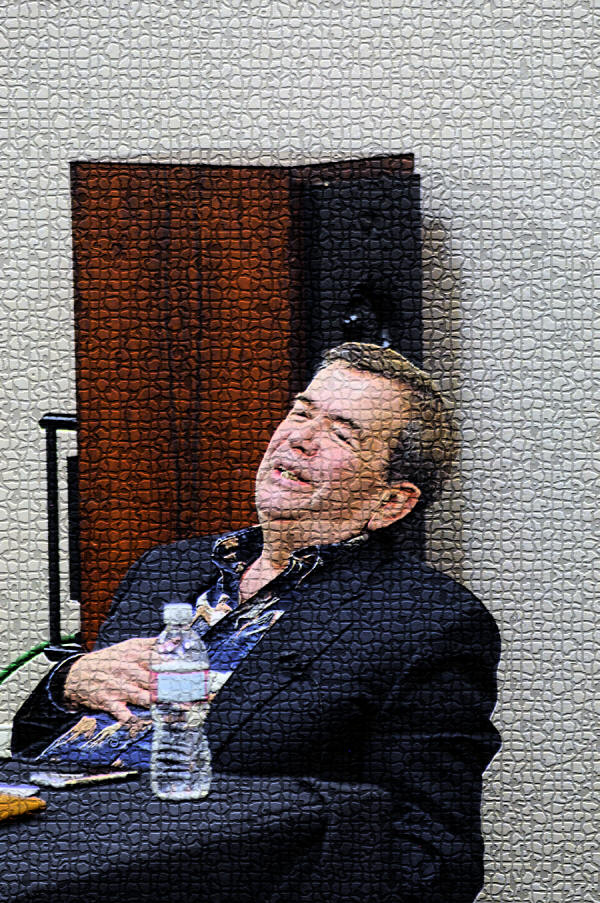

Harry Pearson laughing, RMAF 2009, Denver, CO

Love and Death. Salinas, CA, 2011. Photograph by David W. Robinson.

"Mistah Kurtz – he dead." Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

The word hit the virtual streets of high-audiodom hard last week. I saw it on Facebook, where it rippled outwards at the speed of networking, that ceaseless super highway of gossip, gawkery, and gosh. It hit audio discussion boards, IM, Twitter, and emails in moments. It echoed in that world, reverberating with a decay time that was measured in days, not seconds.

Harry Pearson was gone.

I heard it from Michael Mercer, whose memorium of Harry is published here in tandem with my own thoughts. In Michael's case, this was unsurprising: He knew Harry better than many people, and had worked with him on a daily basis in close quarters for longer than just a few days. Having been a young man when he started at TAS, "Mercer," as Pearson would call him, would dwell in the immediate shadow of a person who had already long since splintered into two separate things. On the one hand, he was a complex human being with a powerful mixture of real strengths and prodigious weaknesses. His close friends reported an engaging, outrageous, Capote-like figure that you could both love and hate, all at the same time. He was a roller-coaster, a tsunami, with opinions on all sorts of topics, high-end audio and music being only a couple of them. He loved film and home theater; he was a bona fide expert on film criticism.

On the other hand, he was a mythic figure in the tightly circumscribed world of fine audio – the HP, who was a mask, a persona, a role, and a legend. His influence was immense, but it could be very dark, cruel, and even cultic. Many were repelled by "HP," the hubris, the puffery, the vanity; I was one of them. At a distance, there was no way that I could come to know the human being; all that I could respond to was the mask.

Unlike many who are writing about Harry Pearson, I did not work with Harry at all, nor did I do any apprentice writing and editing in his shadow. There are a number of well-known audio writers and editors who did, but I'm not one of them. I had started earlier than that, you see.

I should explain this briefly, since it might help you to understand my relationship with Harry Pearson. Otherwise, you won't get the nature of the beast.

My experience with writing and editing goes back decades, starting with the study of journalism for three years in high school, in both California and Brasil. School papers, plus editing my own small underground magazine, whetted my appetite for writing and editing. I took the senior prize for creative writing in Brasil, together with its very gratifying award check, and then went on to college in Portland, Oregon. I did a couple of years of audio production work doing location recordings of local bands for KLC FM at Lewis and Clark College, as I pursued a double major in history and education. After graduation and my movement into teaching history full-time, I kept my hand in writing and editing off to the side by working with or freelancing for a diverse lot of publications over the years: Northwest Chess Magazine, Epson Connection, Northwest Computer News, and The Oregon Business Journal. I've published scholarly articles and book reviews in various university journals, both in-print and online. I have co-edited and co-authored an academic book, and have been paid for editing work in the realm of Information Technology. More are in the wings. I did another year or two in radio work with a local show on information technology issues.

In all of this, I wrote for fun and for profit, as a sideline, because I love doing it. That's why writers write, and editors edit.

In late 1989, I joined an effort to establish an audiophile group in Portland. It came to be known as the Oregon Triode Society. Launching in January of 1990, one of the activities of the OTS was to establish a newsletter. I contributed a small article or two early on. We had some help in the initial editing and layout from Michael Fox, who happened to be writing for TAS at this time. He was very concerned that Harry might find out that he was doing this, however, and so quit after the first two issues. The Board of the OTS then met at my place, and the result was that I ended up as the new Editor-in-Chief of Positive Feedback. I told them that I would do this only if I had carte blanche to take PF where I wanted to go. They agreed, although later I'm quite sure that some of them wish that they hadn't.

PF represented a fusion of three major new forces in publishing, just beginning to emerge in strength by 1990: The personal computer, desktop publishing, and the Internet. (I had first gotten onto the Internet in 1984, when you had to study Unix and have some friendly nerd contacts. Same year as the movie Repo Man. It figures.) As such, we were one of a new wave of small print publications that addressed high-end audio, and that challenged traditional print publication. Before this, freedom of the press belonged to the person who could afford one, as the saying went. But from the early 1990s onwards, that began to change. PF used the power of PCs, desktop publishing, and the ability to find and network with writers and editors all over the country and the world via the Internet, to build our journal. We were punk and edgy and underground from the beginning, with lots of attitude, and a growing editorial group. We were concerned about the audio arts and about community, and weren't much interested in the traditional turf wars that were prevalent between TAS and Stereophile. We also weren't too taken with some of the entrenchment that we saw. PF was therefore an attempt to establish not just a new voice in fine audio publishing, but a new way of looking at things.

As the years went by, we had a number of great writers and editors join the community at PF. It was something outside of the older publishing paradigm, and not subject to the command and control or influence of known figures like Pearson. Therein lay some of the tensions between Harry and me as time went by. The new models emerging from advances in technology were erosive of the earlier significant power that traditional publishing had, and the new audio underground was not willing to accept the status quo just because it existed.

Think Punk. Think Grunge. Think counter-culture.

And now it had computers, software, and the Internet.

Think Die Hard and, "Now I have a gun."

Once you know this, you'll understand more about my relationship with Harry. It developed over time, across a number of years, and via long distance. It wasn't close or personal, and was always edgy and difficult. In fact, it was generally confined to my contacts with him from time to time over editorial issues that he would voice his displeasure about. These usually had to do with his disagreements about what I published at Positive Feedback, my philosophy of the audio arts, the importance of creative community, and the way that I approached audio reviewing. He seemed to have assumed that I needed his grouchy pompous mentoring to "improve your content," and didn't get the fact that I didn't feel a need for his instruction in how to write or edit.

Sometimes his comments would arrive directly. For example, he once scoffed at length about the importance of synergy in audio reviewing. I disagreed with him pretty bluntly. He was defending the old notion of being able to drop the "device under test" [DUT] into place, without any regard for system synergy at all, and being able to immediately evaluate the component. I told him that, in my experience, changing one thing changed everything. He got pretty surly; I told him that he was wrong. He was not happy; I didn't care.

C'est la vie, Harry.

Other times, these concerns were communicated via the back door, through writers or editors at PF who were also working with him. In the late 1990s, one of my senior editors called to say that he had just finished a conversation with Harry in which Pearson had communicated his concern about a photograph that he thought I was going to publish. It was a photo that Harvey "Gizmo" Rosenberg had sent to me after an audio show, with Gizmo in all of his kilted, tubed-headdress glory, and an arm around a rather reserved-looking Pearson. Gizmo thought it was a riot; so did I. Good fun, and a great chance for PF readers to see Harry in a crazy situation, with Gonzo-Dog Gizmo as his chaperone. (I'm pretty sure that Gizmo was not wearing underwear. Harry probably knew this.)

Anyway, Harry didn't call me…he called this mutual contributor to raise the issue. By God, if that photograph was published, he would sue my ass was the gist of what I was hearing from my friend. Our mutual friend, knowing me pretty well, assured Harry that such threats were precisely the way to get me to publish the image. (He was right.) Pearson finally calmed down, backed down, and asked him to ask me if I would please not publish it as a favor to him. Asked as a friendly favor, editor to editor, of course I said that I would refrain.

I didn't actually meet Harry face to face until about ten years ago, at one of the CES events. I remember that we talked briefly about our mutual interest in DSD and SACD, and his enthusiasm for the work of Ed Meitner at EMM Labs. He told me that SACDs and DSD, especially in multichannel, had finally provided the next great advance forward in high-end audio. He was very enthusiastic, and we chatted for a few minutes about it. But Pearson was late coming to this conclusion; I had been trumpeting Ed's great work in my own writing a several years earlier. By this time, around 2006 or so, Harry's prime time with TAS was well behind him, and his relevance to the next generation of audio advancement was no longer clear.

Michael Mercer and Harry Pearson, RMAF 2009: The passing of the torch.

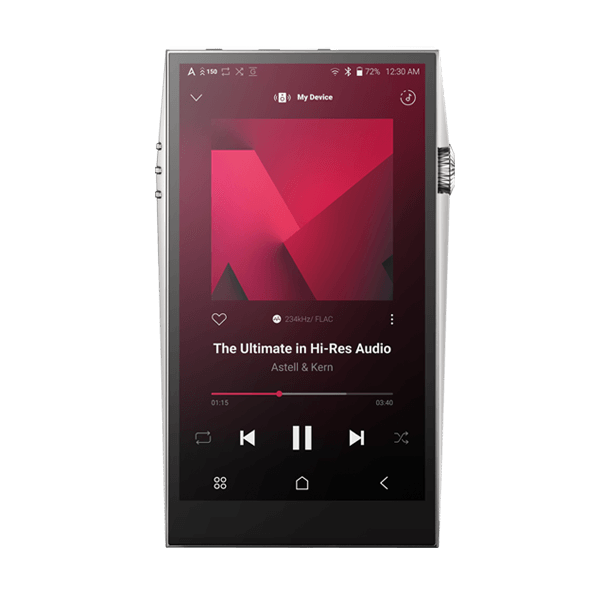

Harry could be quite charming and engaging, of course. In 2009 I saw him again at RMAF, when he gave a seminal seminar presentation on the future of high-end audio. He did make his ongoing support for DSD and multichannel clear. He also pointed to the coming of the personal-fi/head-fi space, and anointed Michael Mercer as a key figure in the next generation of audio writing for this new domain. His vision was clear, and I was impressed by his willingness to take courageous stands about where our audio future should go.

At that same event, I teased back and forth with him in the Atrium at the Marriott Tech Center, as he consumed one chocolate martini after another while flirting lightly with PFO's Carol Clark. Regardless of my numerous deep reservations about "HP," I admit that at such times Harry Pearson the human being was someone who could be a helluva lot of fun to be around. Perhaps if we had gotten a chance to really know each other, instead of simply knowing about each other, or running into each other as very independent people with definite (and conflicting) visions of what fine audio publishing ought to be, we could have been friends. I guess that some things in life you'll never know….

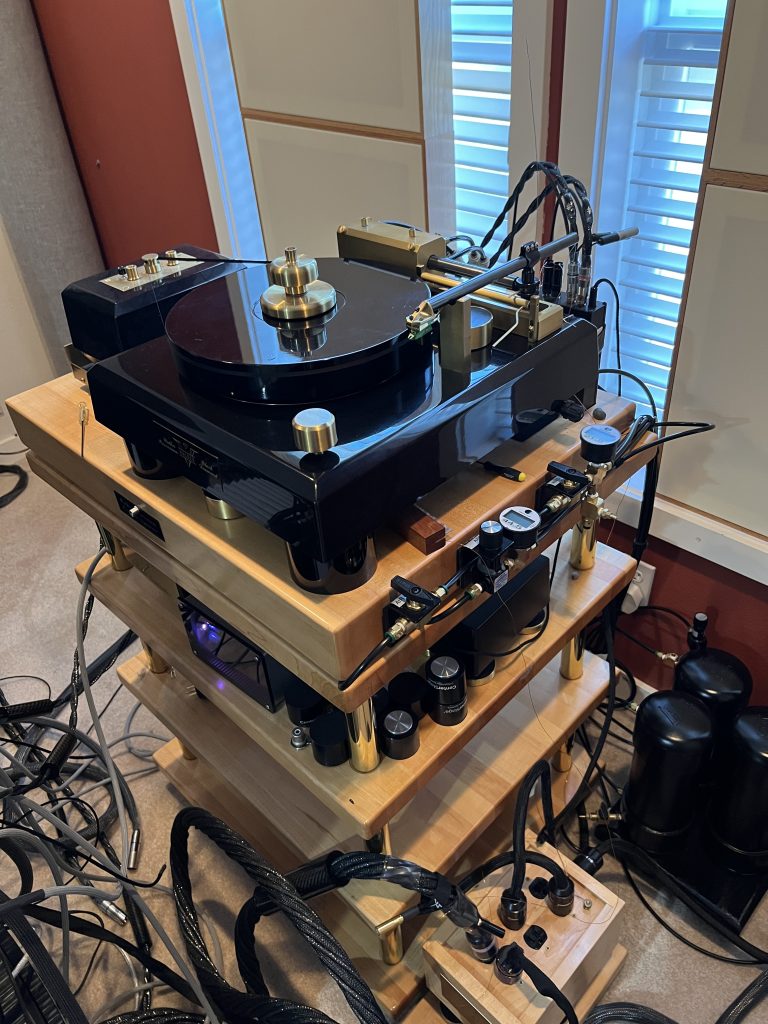

Less attractively, there was the time that Harry and I talked over the phone a couple of years or so ago. It involved a turntable that he had been reviewing, that was supposed to be shipped on to me here at Positive Feedback Online. It was long overdue, and I had been waiting for months for it to arrive. The American distributor had promised repeatedly, but had run into a brick wall with Pearson about sending the turntable in question along. It appeared that he was holding it as something of a hostage, hoping that the distributor would finally send him the model of turntable that he really wanted, instead of the one that he had accepted, and had done not much with.

The distributor was finally forced to put real pressure on Pearson, and Harry finally grudgingly agreed to send it along to me. But as he did so, he called me to tell me bluntly that I wouldn't like the turntable he was shipping to me; it was a real piece of shit, etc., etc. You know: Real "poison the well" sort of stuff.

Me, I was pretty shocked and appalled at this, even given my earlier history with Pearson. I would have fired anyone at PFO who had ever done such a thing. I have to assume that this wasn't the first time that Harry sandbagged an audio component. I informed the distributor involved; he was livid.

Can you blame him?

For me, it was another strike against the "HP" of legend, despite any personal appeal that I might have experienced at other times.

It was during this conversation that he proceeded to tell me that I didn't know what the hell I was doing at PFO – who did I think I was? (This was in our 23rd year of successful publication.) I told him that I didn't need his advice; he told me that he had won an award for his reporting, and that he knew better than me, and so on. I gave him a summary of my background and experience in journalism…we growled at each other back and forth…I told him to go to hell…and then he finally admitted that I might know what I was doing. This was the good, the bad, and the ugly of dealing with Harry Pearson, in a nutshell. He was maddening…but he could also be conciliatory, if you were solid and stood your ground. Not otherwise.

Even Gordon Holt, whom I had some contact with, groused about the legend of HP and his contributions to the rise of high-end audio. Gordon told me that he felt that Pearson's influence and significance were overblown, and that Holt's own foundational work at Stereophile in areas like reviewing and audio vocabulary had been slighted. Nevertheless, he conceded that Pearson had done some important work in helping to define the terminology of fine audio.

Of course, I wasn't alone in my ups and downs with Harry Pearson. I had a number of friends in the audio industry who shared stories with me privately about their experiences with Harry. Many stories of this kind are already circulating in the remembrances and memorials online, and I'm sure that we'll see more in print soon. Some were pretty sad, having to do with very expensive dinners charged to manufacturers and distributors, outrageously-priced bottles of wine likewise put on someone else's credit card, equipment that would sit around Harry's place in Sea Cliff without a review for very long periods of time, repeated refusals to return review samples in anything like a timely and professional manner, a music collection greatly enhanced by free donations of LPs, allegations of quid pro quos, sexual innuendo, Harry's strange ideas of dress or undress with his staff at Sea Cliff, an expensive lifestyle that could not be supported by the finances of TAS…it was a long list. Unfortunately, it would appear that some of what I heard over the years is being triangulated as true now, given some of what I'm reading.

Over time, I came to see Harry Pearson as succumbing to his own cult of personality, of being unable to resist the temptation of playing the public persona for whatever complex of reasons drove him to do so. He benefited from his cultic status among many – though not all – audiophiles, and his pronouncements were viewed as the equivalent of papal decrees. In his prime, Pearson could make or break products, and even some companies, and they knew it. Thus, even those who would tell me confidentially of their repulsion at what they saw as dubious or even (allegedly) corrupt practices would play along, hoping to benefit from Pearson's largesse. One did not wish to commit the sin of lèse majesté with HP, which was a fact that he banked on for many years – until the world changed so much that he was left more-or-less behind the curve of the world that he had helped to create.

I sensed that those of us who were indifferent to his influence and fulminations were a frustration and puzzlement to him.

When Positive Feedback finally merged with Dave and Carol Clark's publication, audioMusings, and then went to full-time online publication in 2002 under the name Positive Feedback Online, it marked the fact that the sea change of audio publishing moving to the Internet via Web-based technologies was well underway. By this time, Harry had already long-since lost TAS to new owners, suffered the indignities of the palace revolt represented by Fi, had actually done some writing for Stereophile(!), and was no more than a very frustrated figurehead at a TAS that he no longer exercised any editorial control over at all.

The full irony was at hand: HP was now a stranger in a world that he had helped to create, the founder at TAS who had been set aside in favor of more businesslike persons who would not recklessly spend the magazine into oblivion. "Businesslike" was something that HP himself never was. (That's how you lose ownership of a magazine, you see.) He was, you see, like Winston Churchill, who famously observed, "My tastes are simple. I am easily satisfied with the best." That way of life had cost him the ownership and control of TAS, and would leave him on the sidelines thereafter.

Internet-based publication, a world that could have given him a platform and a fulcrum for his work, was something that he never seemed very comfortable with. Via mutual friends, I offered to give him an entire section of Positive Feedback Online to publish freely on any area of audio and video that he wanted to. It never came to anything. He tried working with others to go online with his work, but it never seemed to gel. Seventy-seven years of age when he died, he didn't have the energy or the determination to sustain his vision in that setting. Too little, and too late, was our Harry, to the brave new world.

Dr. David W. Robinson, Editor-in-Chief of Positive Feedback Online. Photograph by Lila Ritsema.

And so, what to say in conclusion about Harry Pearson, as I think about his death?

I think that Harry was complex, complicated, intensely human, and subject to the temptations of fame and influence that he could not resist. At his best, he was a very appealing person with a powerful vision of what fine audio could do to transform our experience as human beings, a natural teacher, a wordsmith with perfectionistic tendencies, and a mentor to those willing to put up with his many foibles. His contributions to the language of fine audio, its concepts, and its paradigms were very significant. And he had formidable sensibilities and insights, though some of his judgments were undoubtedly debatable.

At his worst, he was overborne by his strengths, blinded by a certain hubris, was tempted by his fame and influence, and became a victim of his own role and legend. He did not do well with the power and influence that he had for a season, and was capable of misusing it. He was an artist, not a business person, which is not a good thing for an Editor-in-Chief. His concept of "the absolute sound" was itself very suspect in my mind from early on in my own thinking, and was, I believe, an incorrect basis for the audio arts. And Harry's self-indulgence overmastered self-discipline in ways that ultimately undermined the success of his creation, TAS. It would cost him the publication that was his home base, his foundation, and his fortress.

Nevertheless, the world of high-end audio would not have been the same without this very extraordinary, very unique, very flawed human being. No matter what may follow, his passing is the end of an era….

[All photographs and image processing by Robinson, except the portrait of Robinson, by Lila Ritsema]