Wayne Goins, doing his thing...

This next chapter starts with Grant making major moves after his successful adventure with Jimmy Forrest. In our last issue, Grant and the Forrest-led band had completed their first album recorded on December 10 and 19 in 1959 at Delmark Records in Chicago, entitled All The Gin Is Gone (with the second album of outtakes released as Black Forrest about five years later). Grant had returned to St. Louis and, like many other black musicians, was working in strip joints that paid low wages and were run by bar owners who didn't much value the musicians or their worth— they treated them as easily disposable commodities that could be swapped literally for a song. Not all the owners were that way, though—there were a few exceptions, and you're about to be introduced to one of them.

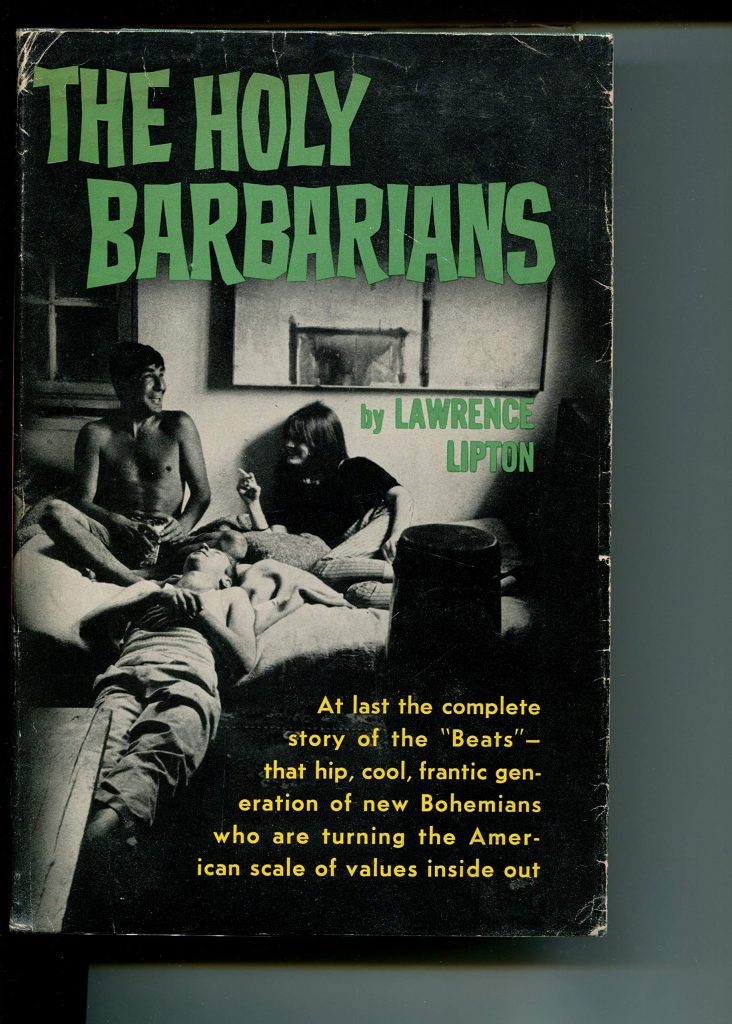

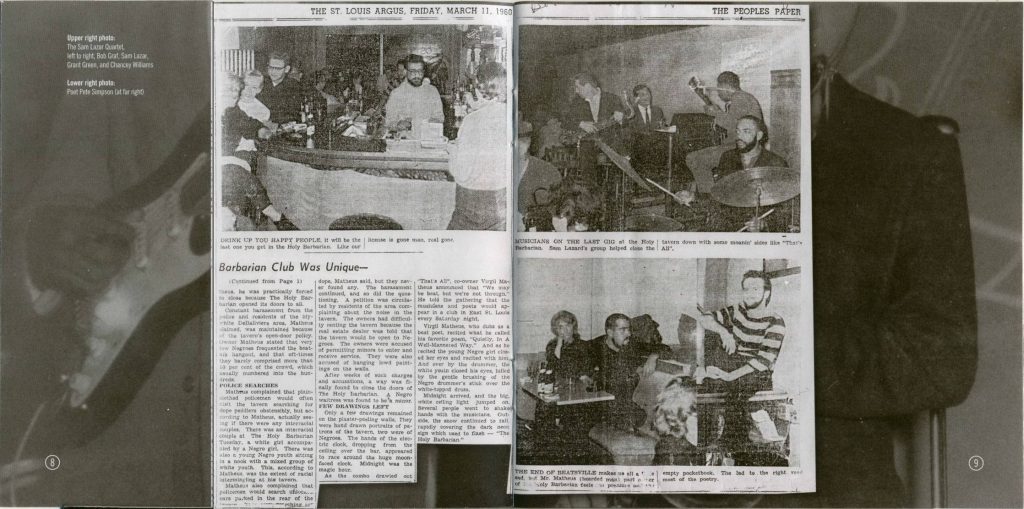

That same December, a hippie-beatnik type by the name of Ollie Matheus had just decided to open a small joint with a very unique atmosphere. He called it the Holy Barbarian, aptly titled after the 1959 book published by Lawrence Lipton—the ultimate chronicling of the lifestyle surrounding the beatnik generation.

The club was located on the East side of town, at 572 De Baliviere. Ollie and his older brother Virgil were ahead of the curve with race relations, and didn't mind having blacks and whites share the same space—as an audience or on stage as performers. After a band Grant played with was unceremoniously kicked out of a strip club down the street, Ollie welcomed them into his brand-new joint—which, in hindsight, he may have opened for the sole purpose of having a place for the band to play.

The band was led by organist Sam Lazar, with Grant on guitar, Chauncey Williams on drums, and tenor sax player Bobby Graf—the only white member of the group. Graf was the oldest member and the one who had the most experience, having previously performed with Count Basie in a small combo, and also Woody Herman's Big Band. This interracial situation caused a lot of problems for Ollie and Virgil Matheus as club owners, but they didn't care. This was the first integrated band in the city's history, and they were proud of it.

Grant and Lazar settled in comfortably to play hipster music in an environment that regularly featured beatnik poets who sported goatees, wore turtleneck sweaters and spouted improvised verses of poetry on stage in the smoke-filled room; then there were the patrons who were there to play chess, not to mention the local artist who routinely painted portraits of the patrons as the live music was being performed. Everyone there seemed to love and appreciate the bohemian atmosphere, since it was they themselves who were there specifically to "make the scene."

The police, on the other hand, didn't like what the place represented, and shut Ollie and Virgil down after only eight weeks of business. That's the bad news.

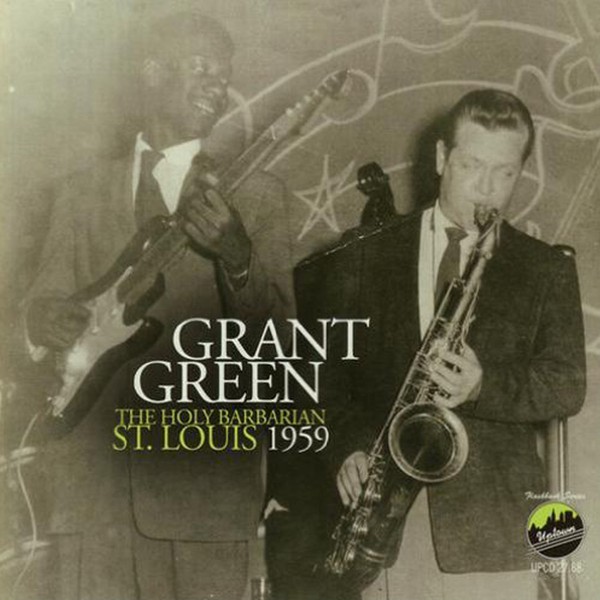

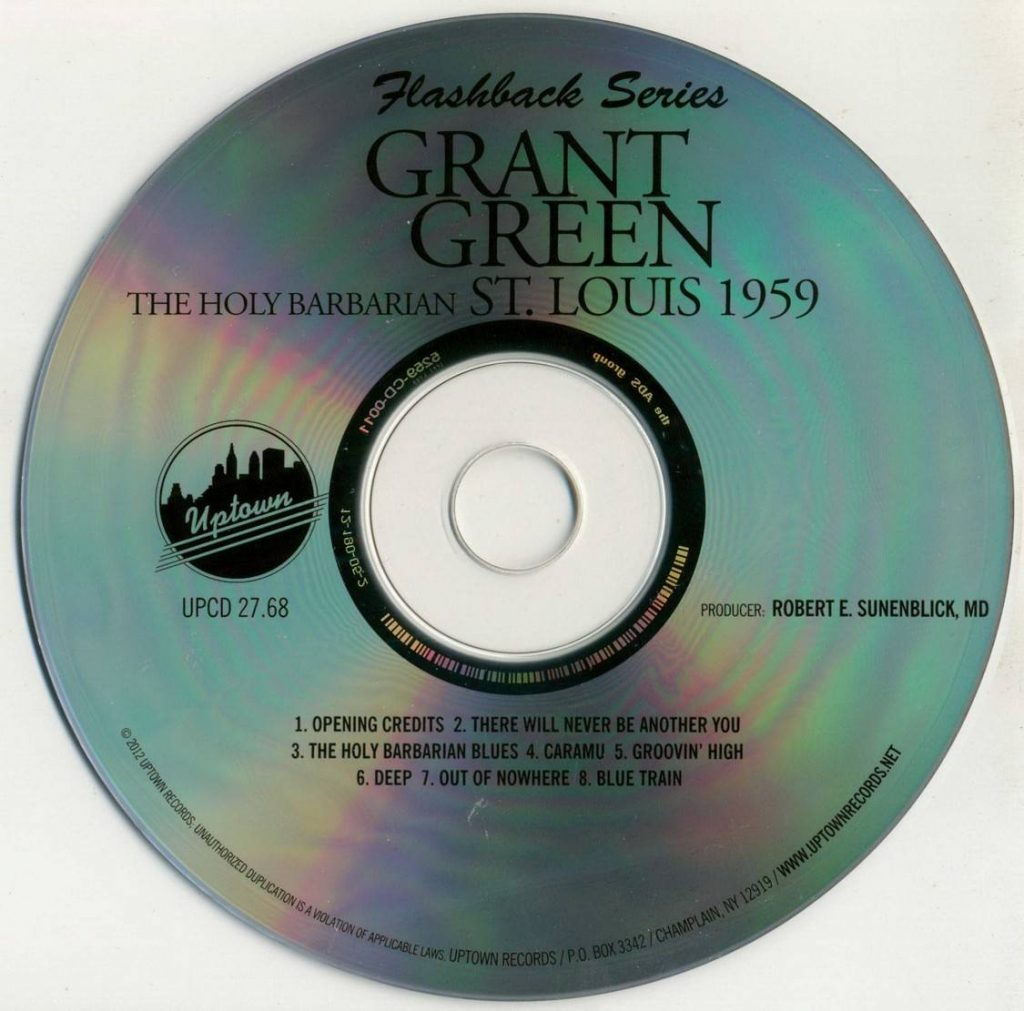

But here's the really good news: There exists not one but two recordings that chronicle the sound of Grant Green during this embryonic stage of his development. The first is an extremely rare album that actually captures his performance at the Holy Barbarian with the Sam Lazar band. (The only located copy of the CD I found was offered for almost $500.) The second recording that exists took place about six months later with the Lazar band in Chicago for an official recording session where they joined legendary Chess Records bassist Willie Dixon. Let's take a closer look at these two albums, shall we? But first, there's this treat:

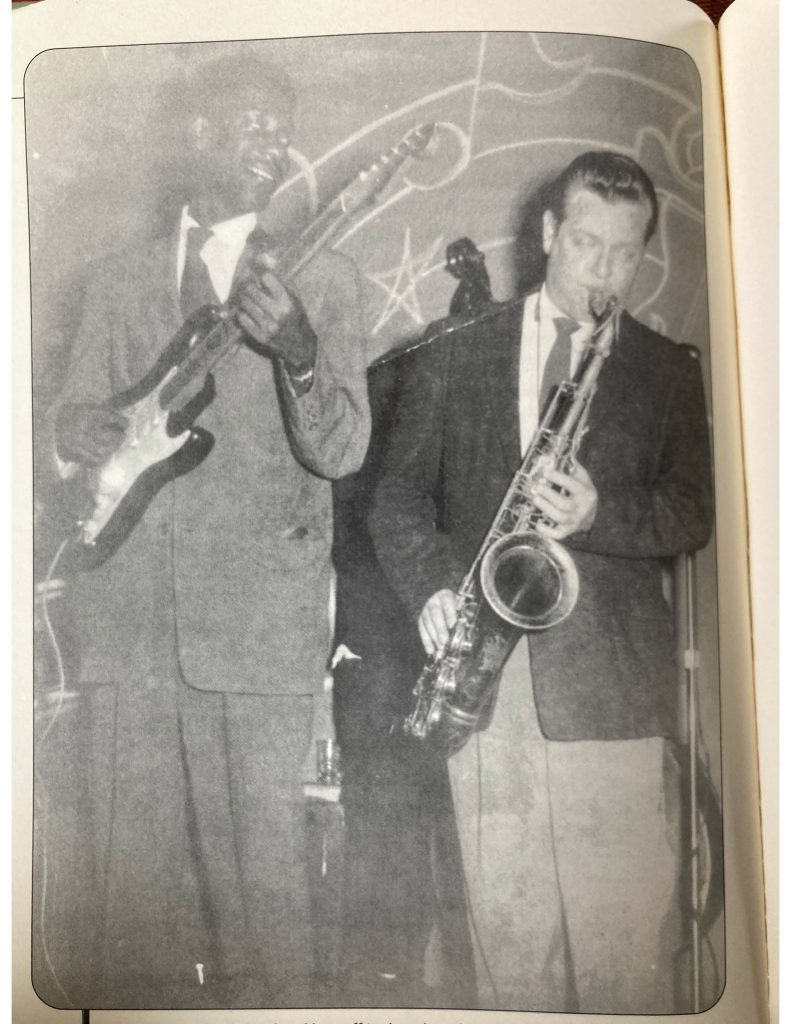

Here we have a photo, credited to the biographer Sharony Andrews Green, who was, at the time, married to Grant's son, Grant Green, Jr. (not to be confused with one of Grant's other sons, Gregory Green, who actually goes by the professional name of—wait for it—Grant Green, Jr.!) Sharony wrote an excellent biography on Grant Green, which included this photo she got from the Matheus family (Ollie's brother Virgil gave it to her). It shows Grant playing not a jazz guitar, but a Fender Stratocaster—which is not at all a jazz guitar, but a popular one that was used to define the sounds of surf music, blues, and rock n' roll. This image of Grant playing a solid-body instead of the typical hollow-body jazz guitar is a rare photo, indeed—and maybe the only one in existence!!

Now I'm really intrigued—was Grant Green actually playing the same guitar that Buddy Holly, Dick Dale, and Jimi Hendrix made famous? I gotta find this album. I go the usual routine of hitting Discogs, and what I discover is a bit shocking: 1) There is no vinyl version of the Holy Barbarian album in existence, to my knowledge; 2) There is a CD version, released in 2012, but there are very few in the world; 3) The one that I found was someone trying to sell it on Amazon, charging $500 (yikes!), and now even that copy is no longer there anymore.

Undaunted, I pressed on, and about four days later (y'all know me: I refuse to accept the notion that there are absolutely no copies available anywhere), I found a website in Barcelona, Spain called Jazz Messengers that had a copy in stock. I quickly snatched it up, and after the euro conversion was done, the price came to $19.20 USD.

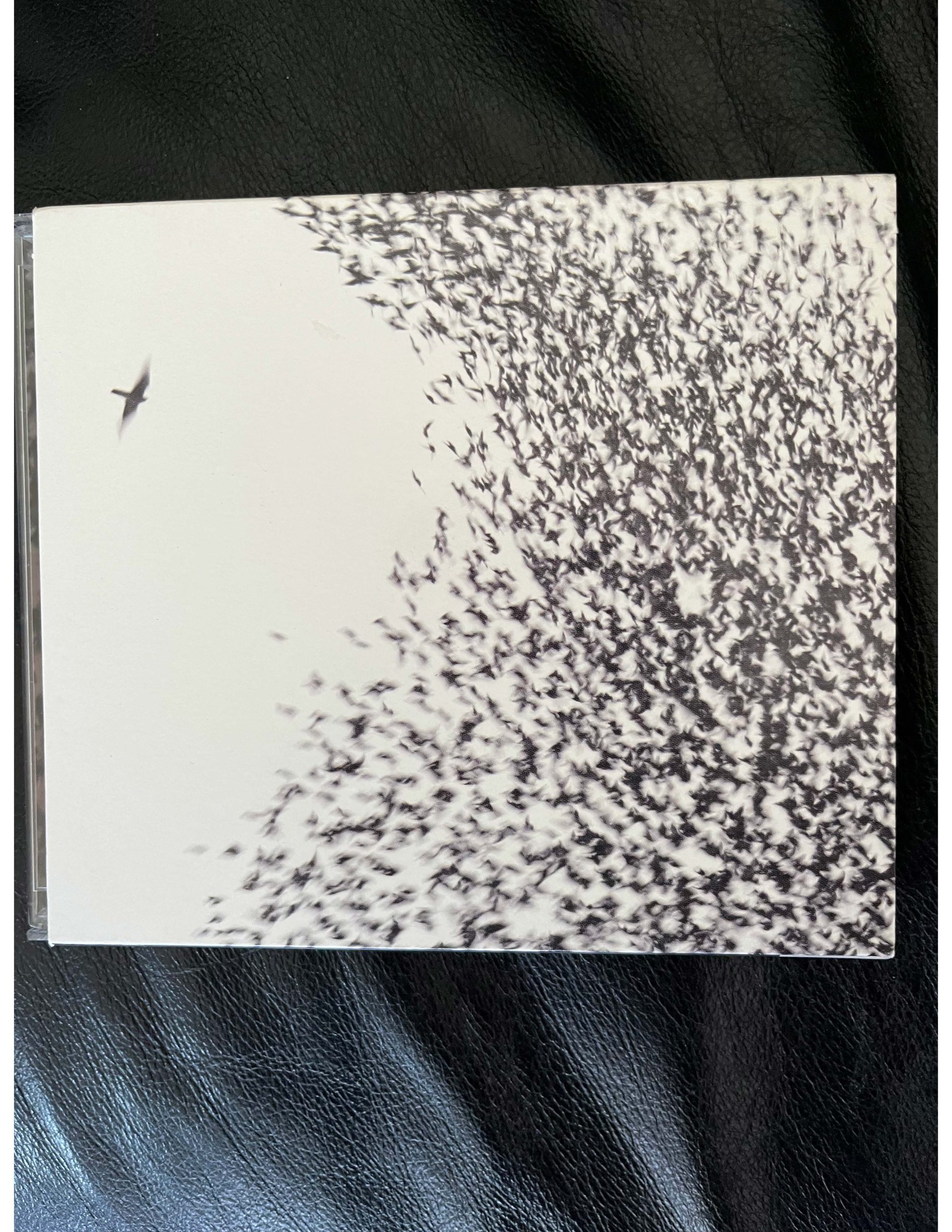

This is the cover photo of the 2012 CD release of the album by Uptown Records. It shows Grant performing live onstage with tenor saxophonist Bobby Graf at the short-lived St. Louis club.

Even though I couldn't by a CD from Discogs, and had to wait for who knows how long to receive my CD in the mail from Spain, I did find a temporary shortcut—I actually went back to Amazon. where I found mp3 files I could download! I purchased the entire digital album (eight tracks) for about $8.99 and started listening immediately. What a treat this was to hear what Grant sounded like as he performed on Christmas Day in December of 1959! Here are the Discogs details surrounding this recording:

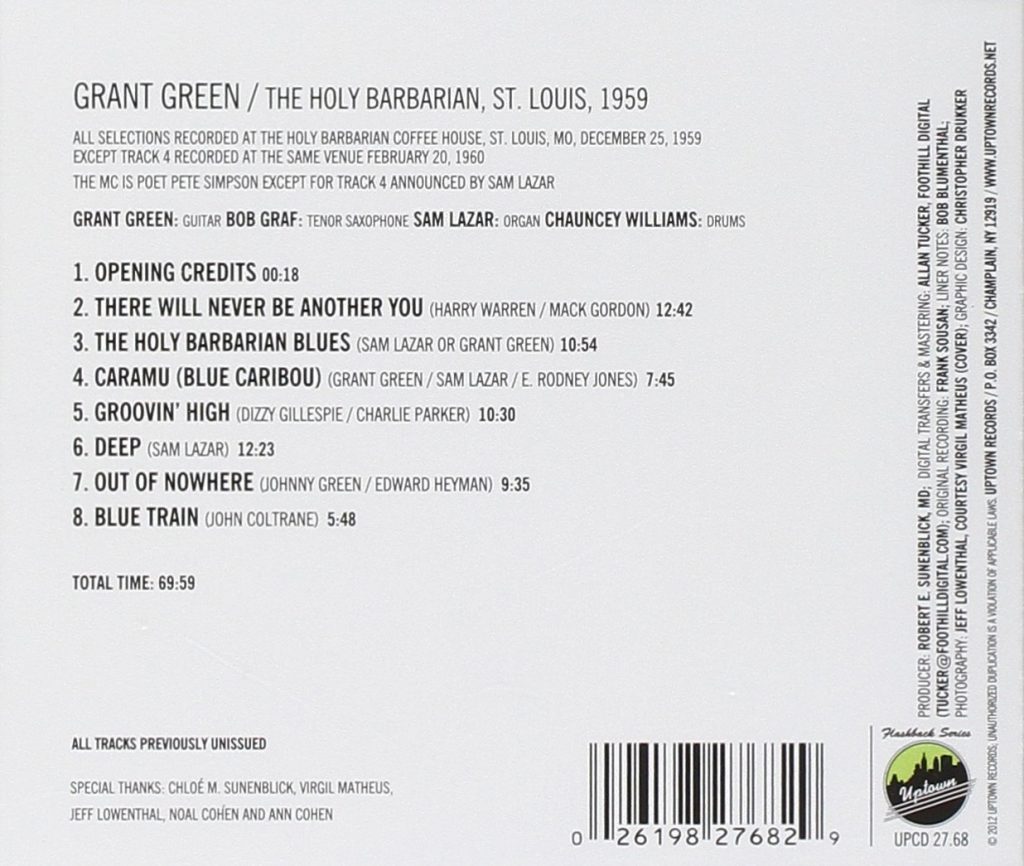

Grant Green, The Holy Barbarian, St. Louis, 1959. Label: Uptown Records. Released: 2012

Tracklist

- Opening Credits 0:18

- There Will Never Be Another You 12:42

- The Holy Barbarian Blues 10:54

- Caramu (Blue Caribou) 7:45

- Groovin' High 10:30

- Deep 12:23

- Out Of Nowhere 9:35

- Blue Train 5:48

Credits

- Tenor Saxophone - Bob Graf

- Organ - Sam Lazar

- Drums - Chauncey Williams

- Guitar - Grant Green

- Graphic Design - Christopher Drukker

- Liner Notes - Bob Blumenthal

- Photography By - Jeff Lowenthal

- Photography By Cover - Courtesy Virgil Matheus

- Producer - Robert E. Sunenblick MD.

- Recording Engineer - Frank Sousan

- Transferred By Digtal Transfers, Mastered By - Allan Tucker

- All selections recorded at the Holy Barbarian Coffee House, St. Louis, MO, December 25, 1959 (Except track 4 recorded at the same venue February 20, 1960.)

- Track 3 is credited to Grant Green or Sam Lazar.

- The MC is poet Pete Simpson except for track 4 announced by Sam Lazar.

- All tracks previously unissued.

- Total time: 69:59

- Matrix / Runout: 259-CD-0011 12-190-05-2 the ADS group

About The Music

On this recording, Frank Sousan (the engineer) must not have had his machine rolling in time to catch the emcee (Pete Simpson) introduce the leader of the band, organist Sam Lazar. The first track of the album, therefore, has him only introducing Bobby Graf, Grant Green, and then Chauncey Williams on drums. The sound quality is really good, considering the fact that it's a live recording in a fairly chatty atmosphere. The seemingly small but appreciative crowd was very much in the holiday spirit.

The band's first song on the CD (the second track on the playlist) is "There Will Never Be Another You," in the key of E♭, with Graf playing the smooth melody upfront. Underneath is Lazar's purring chord progression on the organ. He plays a fairly swingin' sax solo—the licks are right, though he's a bit square with the length of his notes and where he places them (too squarely on top of the beat). Chauncey's straight-forward drum groove is totally in the pocket—he's laid-back, but right and tight. Meanwhile, Sam is getting busier, workin' the levers, literally switching gears, getting a wide array of several gurgling tones like he learned from watching and listening to Jimmy Smith—the man who inspired him to play the Hammond B3.

You don't hear Grant at all until his turn comes after five sax choruses. You can tell Sousan gradually moved closer to Grant's side of the stage—Grant's guitar volume on the recording becomes louder and clearer, raised to the appropriate level. His tone is a little soft and dark at first, then he speaks up with more clarity, and you hear that unique timbre we all have come to recognize (even though he's supposedly playing a Strat?? I will have more to say on this, but later). His patented licks are already there, and he even quotes a phrase from Bizet's opera, Carmen—twice—once at the end of the second chorus, then again near the front end of the third chorus. He uses space very well, letting things breathe after a long stream of eighth notes, employing his well-known trick of the repetitive phrase—playing one particular lick six times in a row to make his point. Grant also uses blues licks in the right places. He takes seven choruses of solos. Lazar takes his gargling B3 organ solo; he enjoys manipulating the draw bars a bit too much for my tastes. On the out-chorus, you hear Grant providing a wonderful counterpoint to the melody underneath Graf's return to the melody. Polite-yet-enthusiastic applause follows.

Next up is the brisk, up-tempo piece called "The Holy Barbarian Blues." It's a simple but syncopated melody played in unison by guitar and sax – Graf's tenor approach sounds a like a combination of Boots Randolph with a bit of Dexter Gordon mixed in. Again, he uses great ideas for lines, but his eighth-notes are still way too stiff and straight to be considered hip. Grant is "choppin' wood" (playing four beats to the bar) very lightly underneath in the background. He comes in smoothly with boppish lines, comfortable with the tempo. He plays very tasty blues licks, and actually sounds a bit like Wes Montgomery here. He once again employs the "repetitive lick" thing, which by now has become one of his hallmarks. At one point, he plays some seriously tasty chromatic riffs that start low and gradually moves up the neck in half-steps. He then plays one-note staccato phrases to great effect; people are cheering out loud when they hear him play the nine-note blues pentatonic riff repeatedly. His timing is really swinging! He takes 22 choruses of solos!

Lazar does what's known in the biz as "the matchbook trick" on his fourth chorus of solos—the organist literally sticks a matchbook cover between two keys to hold one note down in the left hand (usually the note that represents the tonal center of the tune) and plays blistering blues riffs in the right. The crowd cheers enthusiastically when this happens, and he exits his solo with bravura. Chauncey performs a dazzling, syncopated drum solo and the crowd is really digging it—it's probably the best tune on the album. The song fades fast on the out-chorus.

For the next tune, Sam Lazar says, "Here's a song a composition written by our guitarist, Grant Green, entitled ‘Blue Caribou.'" (The title is also listed as "Caramu.") The piece is a swinging blues at medium-tempo in the tonality of F Major. Bobby serves up a good greasy tenor solo, especially when he plays double-time riffs in sixteenth notes over the medium-paced quarter notes laid down by the drums and walking pedal of the organ. Grant's solo comes up and he sounds as relaxed as ever, pacing himself in both register and rhythm to slowly build the intensity over time. He masterfully manipulates quarter notes, eighths, and triplets to create interest and variety…now he's shifting into the repetitive dimension to create a new level of tension. He takes seven choruses before he turns it loose.

Chauncey Williams is really swingin' the drums underneath Grant's solo. Then something odd happens: He seemingly skips his drum solo, but instead shifts to playing straight eighth notes instead of the expected swing groove – it sounds sort of like what kids in my generation grew up culturally recognizing as an Indian "rain dance" groove. The song ends with that, and this suddenly feels to me like an editing decision by the engineer, because it kinda doesn't make any sense from a song form standpoint—something feels missing, and it's not a typical way to end a swing blues tune.

"Groovin' High" by Charlie "Bird" Parker is the next tune, performed in the key of D♭. Both tenor sax and guitar play the head in unison, the tempo paced slower than the usually brisk bop speed this tune is known for. Some might not be aware, but on the recording, Graf is playing the Bird bop melody while Lazar, underneath him, is actually playing the original Paul Whiteman melody and chord changes of "Whispering," the material from which Charlie Parker borrowed to create the bop arrangement—which means that this particular rendition doesn't really sound much like bop at all. Bobby plays three really tasty choruses with sweet licks, and ends on a two-note phrase. Grant plays the last two notes exactly in the same rhythm and register that Graf left off, which is really cool to hear—lets you know he's listening to everything Bobby was putting down. Grant's solo outlines the changes beautifully; he takes his time and paces himself for seven full, relaxed choruses. He gets to stretch out as long as he likes, not worried about any time limit—unlike the relatively constrained conditions when they're in a recording studio where, literally speaking, time is money.

"Deep" is a medium up-tempo blues. On the CD, the song starts as a fade-in, which indicates that the engineer may have again made an editing choice to cut down on the record length of the tune compared to the actual performance. Grant is playing a pretty cool riff underneath the sax who is doing a Lester Young-flavored solo (only less effectively, because Graf plays straight-up-and-down on the beat). They're great licks, it's just not swingin' in his execution—it's still too square. Grant jumps in with his solo, and the guitar does not sound like a Fender Strat. Or maybe Grant can make any guitar he plays sound like…him. Whatever the case may be, he sounds like he's experimenting and stretching out with his ideas more on this solo than any of the previous tunes. He plays no less than 28 choruses, manipulating the rhythm as he superimposes and displaces note groupings to create tension.

When the organ solo begins, the tempo starts flying, although it's not intentional…Grant's comping four-to-the-bar just to keep up. The tempo's going faster and faster, and it's blatantly obvious by now: The drummer is being pulled—dragged—by the walking—no, running—foot pedals of the organ. The tune collapses in a hurried mess—Chauncey Williams basically stops playing drums and lets the organ and sax duke it out in chaotic disarray; the song finally ends in a slow, strip-tease fashion.

The penultimate piece, "Out of Nowhere," is delivered intact—the tempo, key (G Major) and chord changes are spot on correct. There's a really nice tenor solo by Graf, supported by excellent comping by Lazar who uses the draw bars to elicit a wide range of tones. When Grant's turn arrives, he reels off one of the best solos on the album—excellent touch, tone, and flawless execution of ideas. He weaves four choruses of beauty, and he's using all of his favorite patented licks. (At some point in his third chorus, you hear someone in the audience vocal-scatting a bebop solo right along with Grant's inspiring solo!) Once Green is done, you hear him comping sweetly underneath the gurgling Errol Garner-like setting on the organ. Unfortunately, Lazar is switching back and forth waay too much this time to create any kind of consistency for the listener, and you get pretty seasick listening to him this time around.

The finale, "Blue Train," is performed much faster than John Coltrane's version. Grant takes six choruses of bluesy licks, and, unfortunately, you can hear a guy (probably emcee Pete Simpson) discussing some kind of topic with someone, and suddenly the band plays softly as the beat poet gets up on the stage and recites a poem mixing metaphoric phrases from movies, book titles, pop songs, etc. It's a spontaneous series of off-the-cuff remarks using cliché lines, intended to create a vocal work of art both clever and sarcastic. He begins with something about being on a "subway far, far away from Ireland…and how far away can you be? Don't ask me…" He pauses a beat, then: "‘Round and ‘round she goes/where she stops…damn if I know…or care…Kiss me once, kiss me twice; it's been a long long time…you'd be so nice to come home to, but I would prefer you with shoes on, and atoning…yes, lawd, nobody knows the trouble I seen…"

More of this kind of patter follows, then suddenly he yells—loudly—"Heyyy mama… I got a drama!…show me the way to go home…" A few seconds later, after tepid applause, he adds, "Dedicated to the Chamber of Commerce…" The song ends with Simpson promising "more jazz and more poetry," along with an opportunity for the patrons to have their portraits painted in the back of the bar "If you wanna have this evening immortalized by Sir James."

Lazar has a great sound and touch, but my guess is that his career didn't take off because the Blue Note label already had a superstar in organist Jimmy Smith. I also noticed that his walking bass lines weren't nearly as accurate to a given song's chord progression as Jimmy's would have been. Still, it's incredibly impressive that he achieved the performance level that he did considering the limited time he had for developing his skills on the beastly Hammond B3—which was only two and a half years at that point. By the way, this photo pretty much confirms my ears' instincts that Grant Green wasn't playing a Fender Stratocaster on this live album—instead it was more likely a semi-hollowbody Gibson 330 model jazz guitar which would be featured prominently on several album covers to come in his long-standing tenure at Blue Note Records.

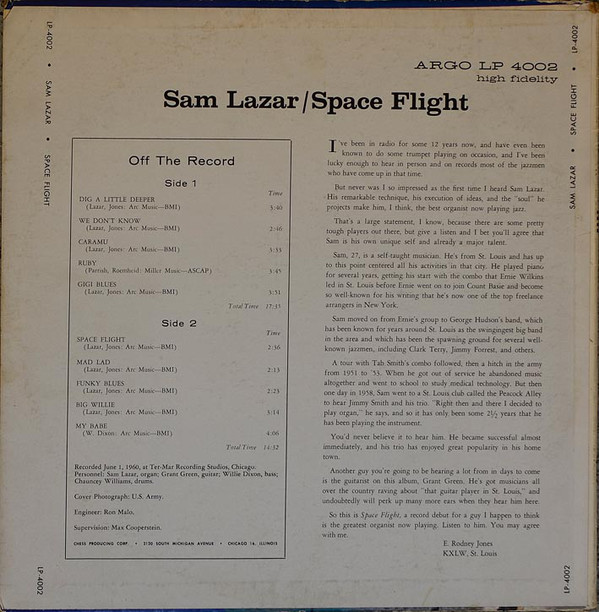

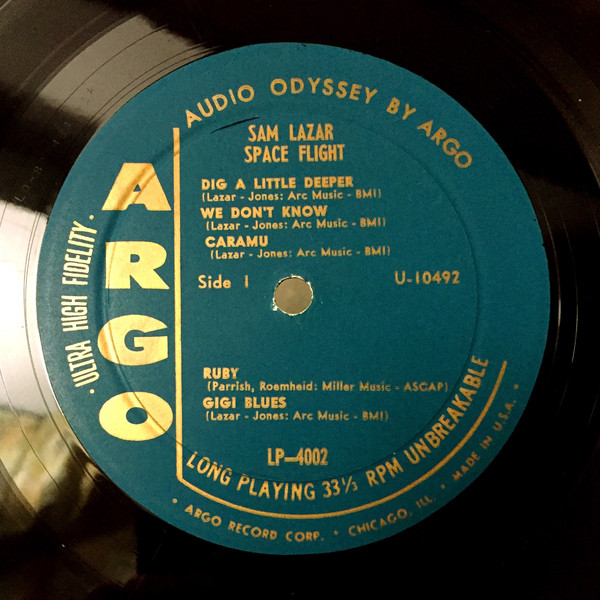

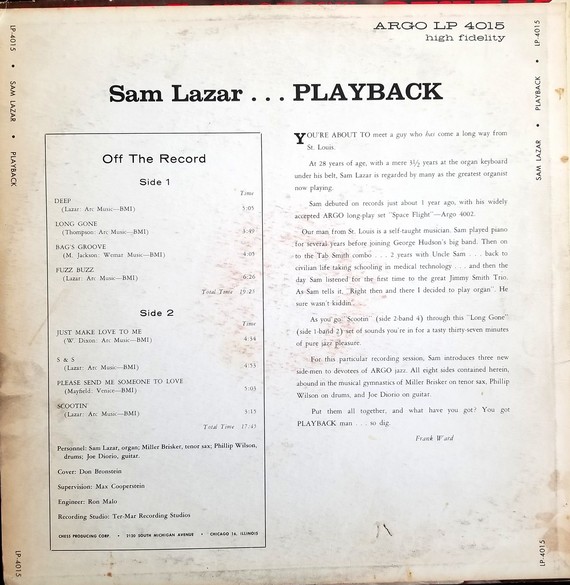

Shortly after this club shut down, Sam got a deal to record in Chicago for Argo Records, a subsidiary of Chess Records, owned by Leonard and Phil Chess. Bassist and producer Willie Dixon served as session leader and bassist on the album recorded on June 1, 1960.

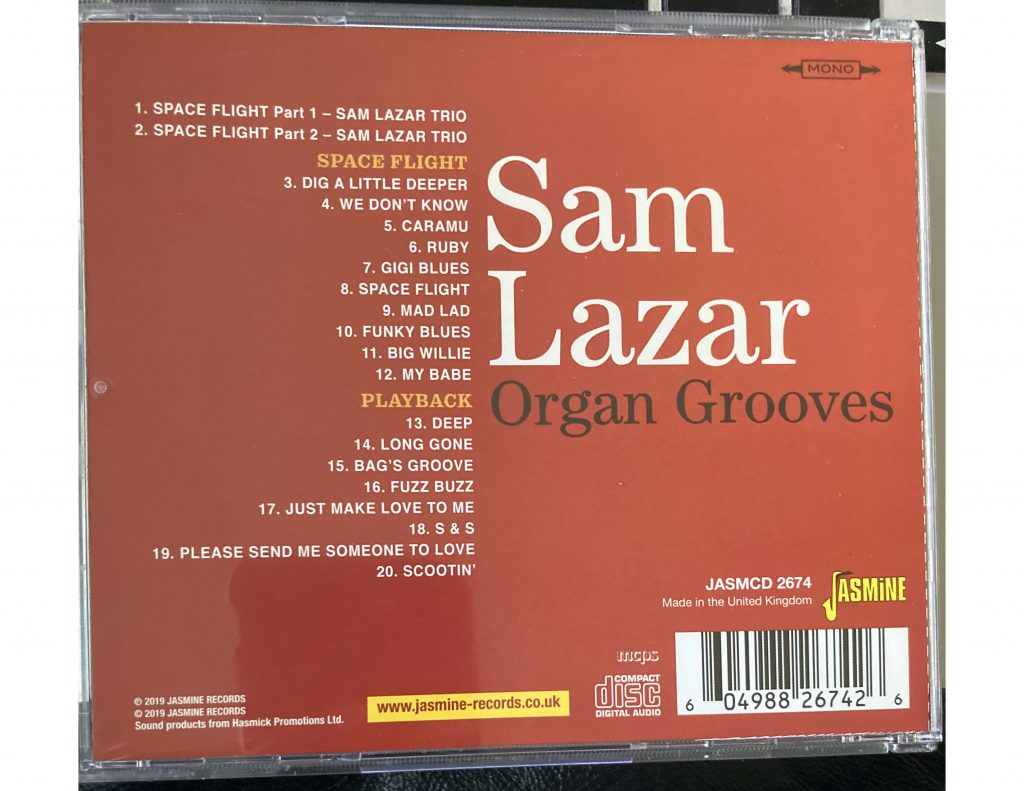

Sam Lazar, Space Flight. Label: Argo (6) – LP-4002, Argo (6) – 4002. Format: Vinyl, LP, Album, Mono. Country: US. Released: 1960. Genre: Jazz. Style: Soul-Jazz

Tracklist

- A1 Dig A Little Deeper 3:40

- A2 We Don't Know 2:46

- A3 Caramu 3:33

- A4 Ruby 3:45

- A5 Gigi Blues 3:51

- B1 Space Flight 2:36

- B2 Mad Lad 2:13

- B3 Funky Blues 2:23

- B4 Big Willie 3:14

- B5 My Babe 4:06

Recorded At – Ter Mar Studios

Credits

- Bass – Willie Dixon

- Drums – Chauncey Williams

- Engineer – Ron Malo

- Guitar – Grant Green

- Organ – Sam Lazar

- Liner Notes – E. Rodney Jones

- Supervised By – Max Cooperstein

- Written-By – Jones* (tracks: A1 to A3, A5 to B4), Lazar* (tracks: A1 to A3, A5 to B4)

- Recorded June 1, 1960, at Ter-Mar Recording Studios, Chicago.

- Cover photograph by U.S. Army.

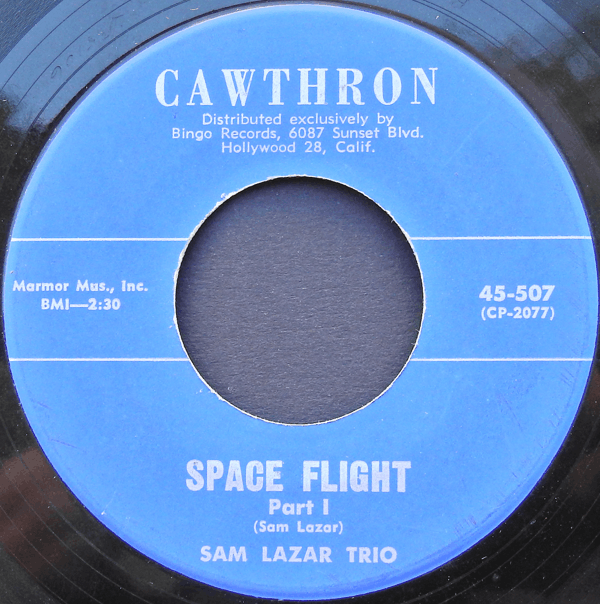

Right about the time that I discover this album, things get a bit confusing for me: It appears that the Cawthron label had released a 45 called "Space Flight."

Details are listed on Discogs as follows:

- Sam Lazar (organ)

- Grant Green (guitar)

- possibly Chauncey Williams or Phillip Wilson (drums)

- Recorded in St. Louis, late 1959.

- (Probably Grant Green's first recording)

For a while, I was under the assumption that this somehow was the first released single from the LP, which is a typical move for a record label to promote the album. Usually, the label picks the most popular song that they anticipate will drive the sales of the entire album, and put that out on side A of the single, with maybe a slightly less important B-side. I was even more confounded, though, when I uncovered the fact that the music heard on this 45 is not identical with the track by the same name on Sam Lazar's LP, Space Flight (Argo LP 4002), placed as the first track on Side 2 of the album.

In a strange twist, two more versions of this 45 RPM appeared in 1960 in quick succession—here's one of them. insert space 45 side1 & 2

During this intermediate period, label owner Dunlap J. Cawthron had apparently moved from St. Louis and relocated to Los Angeles.

I found a copy of this first reissue version of the 45 on Discogs for about $25, listed as VG+ condition. I snagged it, and before it was shipped, the seller wrote me a note:

"Hey Wayne, this 45 has been listed for a long time ... Looking at it again, It's like a decent VG. I think I was a little overzealous in my grading. It plays fine, I'm going to send it to you. But I'm going to give you a refund. It's still a good tune ...You'll like it."

I wrote him back saying how nice I thought his gesture was, and promised to look for a chance to buy his products again.

Okay, back to our story—so now there is a bit of having to "follow the bread crumbs" to figure out exactly what happened here regarding the sequence of events surrounding the many versions of 45s related to "Space Flight." First, the original 45 (the dark blue label) was recorded in St. Louis in late December 1959, well before Grant and Sam made the Chicago session. I also noticed that they recorded without having saxophonist Bob Graf on the album, whose very involvement at the Holy Barbarian was primarily at the insistence of owner Ollie Matheus (who was hell-bent on integrating the band for his own personal reasons.)

The second 45 of "Space Flight" was released when the label owner moved from St. Louis that same year, and took his label and name with him. He reprinted the disc with new label details on the 45, including his employment of Bingo Records as the distributor. Meanwhile, evidently the Chicago session for Argo occurs somewhere between the original recording session in St. Louis and the time Cawthron is secure in Los Angeles.

But the plot thickens. There is yet a third issue released (most likely done not long after his second issue) when Cawthron realized that the Chess/Argo label had Lazar re-record "Space Flight" in June for their album, and he was hoping he could capitalize on it by releasing his own, colored vinyl version of his original recording. The blue wax issue features his PO Box 11371 address on the front of the 45.

A bit more about this somewhat mysterious Dunlap James Cawthron: Besides his main job as a traveling meat inspector, Cawthron not only owned Cawthron Records, but at some point during the 50s and 60s, also owned C & C Records, Allegro, and Credence. A man named Armin Büttner posted incredible details on the evolution of the "Space Flight" 45, and his link is posted HERE.

Notice that the details reveal a level of uncertainty regarding whether it is actually drummer Chauncey Williams (who played with Grant and Sam at the Holy Barbarian) or Phillip Wilson (with whom I am not familiar at this time) on that first record date in St. Louis. According to the liner notes, we know for certain that it's Chauncey on the Argo recording in Chicago when they re-recorded the tune.

Upon listening to both sides of the 45, and then each track of the LP, not only is "Space Flight" not the same version, I realized that "Space Flight Part II" (the B-side of the Cawthron's original 45) became the song now labeled as "Big Willie" on the Argo album—renamed for Chess bassist/producer Willie Dixon. In like fashion, "Mad Lad" was named for E. Rodney Jones—the liner note writer, popular St. Louis radio personality, part-time emcee and self-appointed co-writer of some of the tunes listed on the album.

Earl Rodney Jones (who met both Green and Lazar while they were all based out of St. Louis) eventually left the St. Louis KXLW radio station that he was affiliated with, and jumped over to Chicago's WVON (letters that stood for the "Voice Of the Negro"), which was where his "Mad Lad" moniker gained notoriety. Not coincidentally, WVON was an in-house station Leonard Chess also owned, which allowed them even more control (and income) over the airwaves for Chess Records who also owned ARC Music, the publishing arm of all of the songs written by Dixon and other artists who happened to record for the label.

Okay, now that we've thoroughly discussed these three renditions of the 45, let's get back to the Argo Records Space Flight LP and dissect each track of the music, one tune at a time.

Taking Off

"Dig a Little Deeper" is a basic 12-bar blues in the key of F with a simple, repetitive lick for a melody. It has a groove that starts out like Booker T. & The MG's "Green Onions," but shifts quickly into a jazzy-blues shuffle. Grant plays the melody upfront twice in unison with Lazar, takes a quick single-note solo for two choruses, and he sounds incredibly similar to Charlie Christian—maybe more than any other time I've heard him do so at this point. He then drops down into a double-stop riff underneath the organ as Lazar grinds his way with a heavy-vibrato-laden setting on his Hammond B3. His solo is long and repetitious, lasting for eight rounds, as Chauncey tries to build momentum and excitement underneath. The song fades with Grant playing the melody again after Lazar's solos are done.

"We Don't Know" is another pretty simple, repetitive melody. This time it's centered loosely around a minor tonality, but in the same key and tempo as ‘Dig.' This tune uses the foot pedal work of Lazar instead of the acoustic bass line of Willie Dixon.

"Caramu," a tune that Grant Green penned, starts as a bright bossa nova groove in the melody, but Chauncey doesn't go with the straight bossa feel, he just keeps the shuffle groove going, which creates an interesting feel—straight eighths superimposed on swing eighth notes. Just as the other two, the tune shifts to a normal 12-bar blues using all dominant seventh chords for the solos. Willie Dixon is again on acoustic bass playing pretty solid, yet uncomplicated and punctuated lines. Grant takes two lean solo choruses before handing them over to Lazar, who starts out simply, but after two choruses, shifts his draw bars to the more gargling, rotating Leslie speaker sound that Jimmy Smith patented. After about six choruses, they get back to the melody and the tune ends quickly. By now it becomes apparent to me that, based on the tone of his guitar, Grant might very well be playing that Stratocaster we saw in the photo and not the Gibson jazz guitar he is seen playing in the liner note insert of the Barbarian album—his tone is significantly leaner, more trebly and with more sustain—all signs that point to a solid body. Not only that, it wouldn't surprise me if it were a Strat—after all, he is in Chicago, where people like Buddy Guy, Otis Rush, and Magic Sam all made their marks using Stratocasters early in their recording careers at both Chess and Cobra Records.

"Ruby" is a song that sounds a bit like the only person who understood what the chord changes were supposed to be might have been Sam Lazar, because Willie Dixon had no clue about what direction the band was supposed to go. Grant and Lazar sound like they are not at all on the same page either. Williams is just keeping time on the drums. Basically, this song is a total hot mess, and they probably should have never released it—there is absolutely no cohesion, direction, or excitement to it whatsoever.

"Gigi Blues" starts out with a kind of tribal drum beat reminiscent of the "rain dance" groove heard on the live album, then shifts to an up-tempo swing where Grant takes two percolating Charlie Christian-tinged solos upfront. Dixon is holding on and seems fairly comfortable playing the old-style jump-blues bass lines using the arpeggios of the chord as a safe outline. Lazar starts simple enough with blues licks for the first three rounds, then in his fourth through tenth chorus he does the "matchbook trick," and solos with screaming intense lead riffs over the top, while Williams drives, slapping down hard on beats two and four. The drummer leads the band as they shift back to the tribal chant groove, and this now explains that edit on the live album, because it sounds exactly like what they did in the Holy Barbarian.

"Space Flight" is an up-tempo shuffle similar to the first track, "Dig A Little Deeper," and played in the same key of F, except it's faster, edgier, and has a different melody used as the main theme. It has a lot more energy, which probably explains why it was chosen for release as the single. Grant takes three quick choruses using a trebly tone for his solo (typical for single-coil pickups used in Stratocasters!) before it's handed over to Lazar, who takes his routine matchbook-flavored solo. The problem with this piece is that the shuffle of the snare drum is mixed a bit too loud, and so is the wood-chopping rhythm of Grant Green's trebly Strat-tone used for his rhythm guitar. They quickly dive back into to the head and land the plane safely.

"Mad Lad," the tune dedicated to E. Rodney Jones' radio moniker, is a real cooker—it's the fastest tempo on the album, has the similar chord changes and key (F) as "Space Flight," only lasts two minutes, and could almost be viewed as "Space Flight Part III."

"Funky Blues" is basically a medium-fast, 6/8-metered gospel groove that has the similar feel and progression that can be heard in the tune, "Drown In my Own Tears" made popular by Ray Charles. They play through the tune once, and Grant takes a very earthy lead solo on the second half of the tune. He circles around for one full chorus—but based on the changes from Lazar (who made a wrong turn during the chord progression), it actually sounds as if Grant both entered and exited at the wrong spot.

"Big Willie" is yet another mid- to -up-tempo jump blues. Basically, this represents a re-recorded version of the tune identified as "Space Flight Part II" from the Cawthron (2nd edition) 45 release from Los Angeles. Compared to the Cawthron version, it's a bit milder—the melody has been shifted forward by a few beats, and the tempo is brighter, cleaner. The overall sound and approach are delivered more gently and smoother, largely due to the clean punchy bass line of Dixon's old-school acoustic bass style, which lightens up the mood compared to the hard-driving organ pedal work of Lazar. Grant Green takes three choruses up front with tasty Charlie Christian-inspired jazz licks intertwined with blues lines. This solo is significantly better than the St. Louis studio version, and it shows just how much Grant has grown in literally a matter of months.

"My Babe" has the same fast pace as the other tunes. It was originally written as a song with lyrics for harmonica player Little Walter by Wille Dixon, but this tune doesn't have nearly the same feel as the Dixon original—it just sounds like another brisk jazz-blues tune. There's nothing unique or clever about it. What's worse is that the drummer Chauncey Williams seemed to be clueless about when and where to land the plane (end the tune), drumming right through the ritard, without slowing down whatsoever until it was basically too late to make a clean ending.

With the exception of "Ruby" (played in the key of C Major), every song on the album is basically in F (although "We Don't Know" is pitched in F#, which might be a pitch speed issue from the tape transfer – most likely it was also in the key of F). This might explain why "Ruby" was such a mess—maybe certain players on the session had a problem dealing with chord changes that weren't based simply in the comfortable key of F. The tune, written by Mitchell Parrish, is the theme melody taken from the 1952 movie, Ruby Gentry starring Jennifer Jones, Charlton Heston and Karl Malden. Ray Charles did a fantastic vocal version of the tune in 1960, complete with strings and backing female vocal choir. Clearly in this case, though, the band was not well-versed in the chord progression—least of all Dixon, who was lost from start to finish on the acoustic bass. Most likely the piece was chosen by Lazar for the same reason "Funky Blues" was chosen—they both have the influence of Ray Charles lurking over Sam's subconscious shoulder.

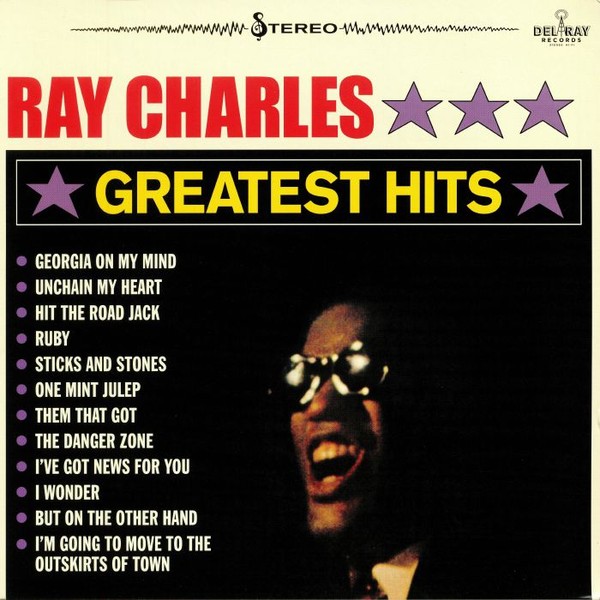

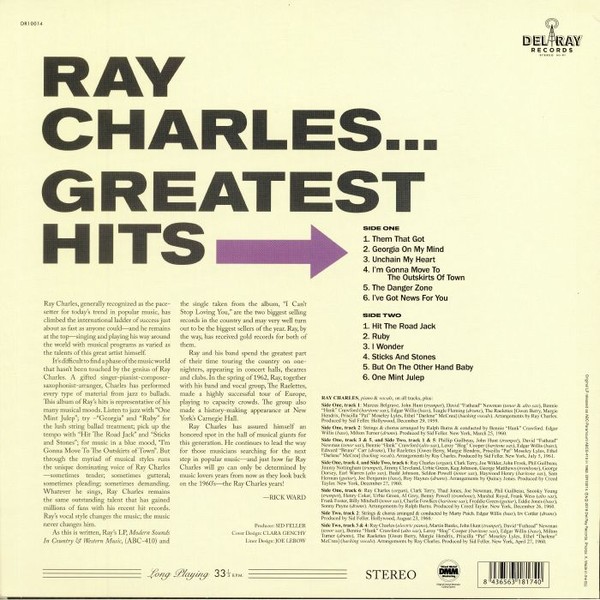

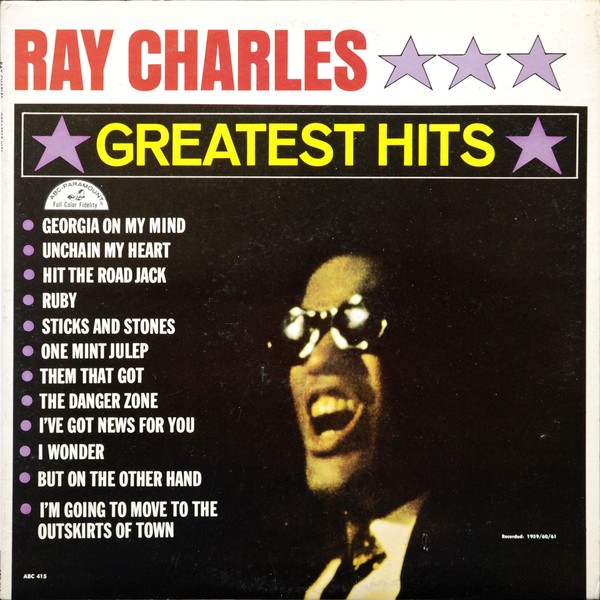

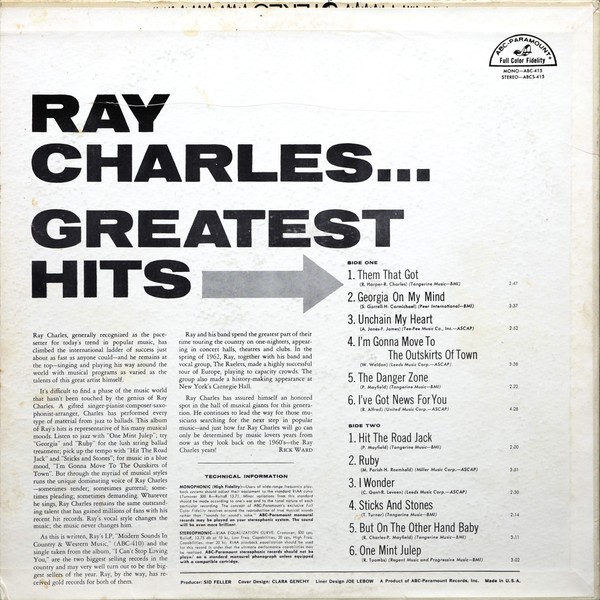

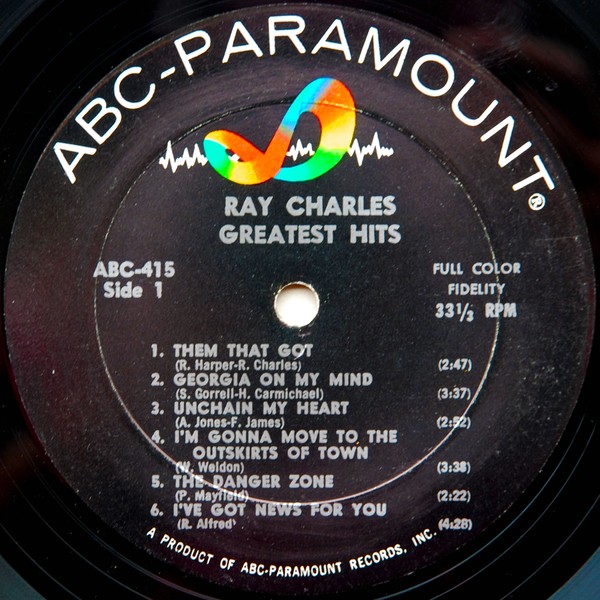

A bit of a side note: The Ray Charles rendition of "Ruby" is—much to my surprise—not at all easy to find, at least initially. Of the many dozens of albums and collections that exist on the market under Ray's name, there was only one place I could find this tune—and it was nowhere to be found on a CD. I could only find it on vinyl from a label called Del Ray (not sure if that was Charles' own label or not), and "Ruby" was one of twelve tracks on this unique Greatest Hits collection.

According to Discogs, this album was originally released as ABC-Paramount ABCS-415 in 1962. It finally dawned on me that the reason I couldn't find it was because by then Ray had jumped ship and left the legendary Atlantic Records (where all of his career-launching hits were done) and moved to ABC. I quickly got on Discogs and snagged an original 1962 issue, in mint condition, and not in stereo, but MONO, which, to me, was even better. The tune I was looking for was found on Track 2 of Side 2.

Later that day…

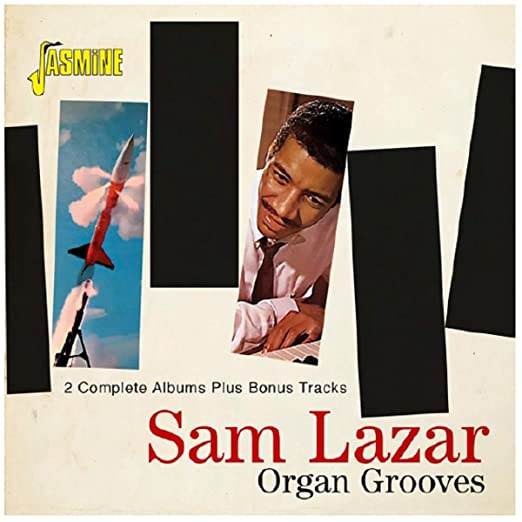

Just as I was finishing this portion of the article, I decided to watch the Ruby Gentry movie (filmed only in black & white in 1952)…I made a nice sandwich, grabbed a beer, and settled in. About an hour later my wife came home, brought something in from the mailbox—evidently Amazon doesn't take days off—and inside the brown package was something I'd ordered online but didn't think it would be here by the time I needed to finish this piece. It was the CD called Organ Grooves, which contains the first two albums of Sam Lazar, plus the original single sides of "Space Flight" 45, with Parts I and II.

This is where things get really interesting, for the CD confirms certain issues regarding my suspicions about the who-what-how-when-where-why in this Lazar saga. More interestingly though, the CD actually revealed a couple of flaws in the liner notes comments—I'll get to that in a minute. For now, though, let's talk about how happy I was to receive this disc; it couldn't have come at a better time.

I ripped off the cellophane and leaned right into the six-paneled liner notes tucked inside the plastic jewel case. The CD features three different portions: 1) both sides of the "Space Flight" 45; 2) the complete Space Flight LP, and 3) the complete Playback LP, which, for me, was just great bonus material since I was primarily intent on digging up the dirt related to Grant Green (who was never on that second album). So, in addition to what I needed, basically I got a free album of eight songs – yay!

The liner notes, written by Bob Fisher in 2018, mentions the fact that although Lazar was trying to make his mark in the industry, far ahead of his reputation was not only Jimmy Smith, but also Jimmy McGriff and Shirley Scott. (I also thought of other competitors like "Brother" Jack McDuff, who'd just released his first album in January that same year; or Richard "Groove" Holmes, who was yet to come on the scene in 1961.)

The CD liner notes includes the original notes on the 1960 LP release, written by E. Rodney Jones, who mentions the fact that Lazar is from St. Louis, and had been motivated to learn jazz organ after having what equates to a religious experience when hearing Jimmy Smith play at the Peacock Alley, a local club in town. While it was admirable for Lazar to have come so far after only two and a half years of playing the instrument, when one listens to the album closely, Sam's shortcomings aren't that had to spot (hence, the nature of my earlier criticisms in this article).

Jones goes on to mention the fact that he thought Grant Green was going to be an artist definitely worth talking about in the near future (he was, of course, right about that), but he goes quite a bit too far when he says he thinks Lazar is the greatest organist on the scene—that's just ludicrous.

But that's not the real problem with the liner notes. The trouble appears when it becomes apparent that Fisher thinks that the Chess/Argo 45 was released before the Cawthron 45. Fisher reveals that a Chess talent scout heard the Lazar/Grant tandem playing on the St. Louis release of the "Space Flight" 45, which makes sense. He is also correct in describing the version of "Space Flight" listed as track 8 on this disc is different than the one on the 1960 Cawthron 45. Indeed, it was really interesting to hear the discrepancy between the Cawthron version versus the Argo re-recorded rendition —Cawthron's version is much more distorted and rougher around the edges, both sonically and performance-wise.

But then he says that Dunlap Cawthron was newly arrived in St. Louis from Los Angeles, and this is incorrect. In fact, he had it backwards, and I also don't think Fisher realized that there were not only two but three Cawthron releases—the first was the original, the second was immediately after he left St. Louis, and a third (blue wax) was released after Cawthron tried to cash in even more from the Argo signing. The second and third were both released from Los Angeles, and the 45 on the original recording is the only one that claims St. Louis on the label. To be fair, it's an easy mistake for Fisher to make, since all three of these happened in rapid succession (all within months of each other) with all three labels using a blue background with gray lettering. It even confused me—but my mind wouldn't rest until I dug deep enough to untangle the sequence.

Unfortunately, Fisher makes another mistake when he says that although he's not quite sure who the bass player (?) is on the Cawthron 45, he thinks its Chauncey Williams! (Okay, admittedly, this one's a little bit harder to ignore.) We all know that Chauncey's the drummer, and that the original 45 had no bass player—it was Lazar using foot pedals for the session, and the disc clearly indicates that the trio of organ, guitar and drums consisted of Lazar, Green, and Williams—otherwise, who would have the phantom fourth wheel playing drums if Chauncey was playing bass?

Fisher rallies back and totally redeems himself when he sheds light on the timeline that lists multiple Billboard and Cashbox word-for-word quotes from the magazines that clarified the fact that these positive reviews played a hand in garnering attention of the Chess execs who always kept a close eye on the trade magazines to see what their blues and jazz artists' chart positions were as they shifted from week to week. Fisher quotes the June 13, 1960 entry which announced that Chess had acquired Lazar's contract sometime shortly after spying a positive review posted by Billboard on May 9, and other positive review posted in Cashbox on June 11 about how hot the Cawthron single was. Finally, Fisher shows the official statement in the press by Jack Tracy—the Chess talent scout who claims the credit for "discovering the trio in St. Looey." Tracy adds that the Argo single, "Space Flight" (side A) with "Dig A Little Deeper" as the B-side would be forthcoming.

If you haven't already figured it out, this means there's yet another version of the "Space Flight" 45 out there now, and this time it has the Argo label on it. Here is a version of what the preview copy looked like, and notice that "Space Flight" is on Side 2, while "Dig A Little Deeper" is featured on Side 1.

This was followed by the official, hard-to-find "black label" release of Argo's official version of "Space Flight."

Another interesting side note: On Playback, the second Sam Lazar album (released in summer of 1962) included on this Organ Grooves two-fer CD disc, the band plays a version of "Deep," the song that Grant performed with the Lazar quartet on the Holy Barbarian live recording (track 6). Sadly, the studio guitarist on the Playback LP, Joe Diorio (who is, by the way, a great bebop specialist and highly regarded jazz educator), got turned around when Lazar dropped two beats in the chord progression due to his faulty pedal work; Diorio never caught back up and was out of sync for remainder of the lengthy organ solo until the main melody came back around several minutes later. Were it not for that foot pedal flub, this would have been a fantastic take—by far a more swinging rendition than the live Barbarian version. More importantly, however, it totally explains that wild vamp at the end of the live rendition, which made no sense at all to the listener of the Barbarian CD, because the intro was—at this point—never heard (and this studio version of "Deep" wasn't recorded or released until more than two years later), so there was no reasoning as to why they ended the tune in the chaotic, seemingly haphazard manner in which they did. But it's nice to finally be able to put the tune into its proper context.

Looking ahead…

Moving on, we now turn our attention toward Grant Green's big move to the Big Apple, where he is greeted with open arms by none other than alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson, who not only "discovered" Green while traveling through St. Louis, but also makes the proper introduction to Blue Note owner Alfred Lion, who then offers Grant a deal that will change his life forever. We will dig deeper into the details of his first sessions with Donaldson and others at Rudy Van Gelder's legendary recording studio where Grant's first sides were captured.

Until then, keep on swingin'!

Wayne Goins' audio system for this article

As usual, the workload is generally divided up between my two separate turntable rigs which are individually set up for mono recordings and stereo recordings. The mono setup was on my Technics SL 1200 MK2 turntable, with the Hana MSL mono cartridge mounted on the tonearm. I have the Technics running through channel 5 of the Rega Brio integrated amplifier, with the Rega Apollo CD player ready whenever I need it—which I certainly did for this issue!

The vinyl was powered by my trusty Modwright combo of the PH 9.0 and the MWPS power supply that drives it. As always, I used AudioQuest (King Cobra Red, Diamondback Blue, and Goldengate Red) audio interconnects. All my Rega components sit on my sturdy Pangea rack.

Next to it sits the stereo rig, which includes my trusty Rega Planar 6 with a mounted Hana ML stereo cartridge and the accompanying speed 33/45 rpm speed controller. This is tastily paired with the Musical Surroundings NOVA III receiver, powered by the accompanying LCPS power supply. To close the deal, both rigs are driven through the my splendid Spendors—A5 model speakers. I use an Achromat turntable mat for my platters to enjoy an extra-smooth ride. With regard to interconnects, I used Grover ZX+ cables to go from the Nova III to the turntable, while keeping continuity with the same brand of interconnects I used on the other rig: a pair of 2m length AudioQuest Diamondback Blue and King Cobra Red RCA cables. All this equipment sits safely on a Line Phono turntable stand.

For my ultimate headphone listening experience for both CD and vinyl, I use my trusty Sennheiser HD 650 Open Back Professional Headphones.