All components in BOLD are loaned; all components in standard face are owned by me. Last updated 07/15/2022

LOUDSPEAKERS

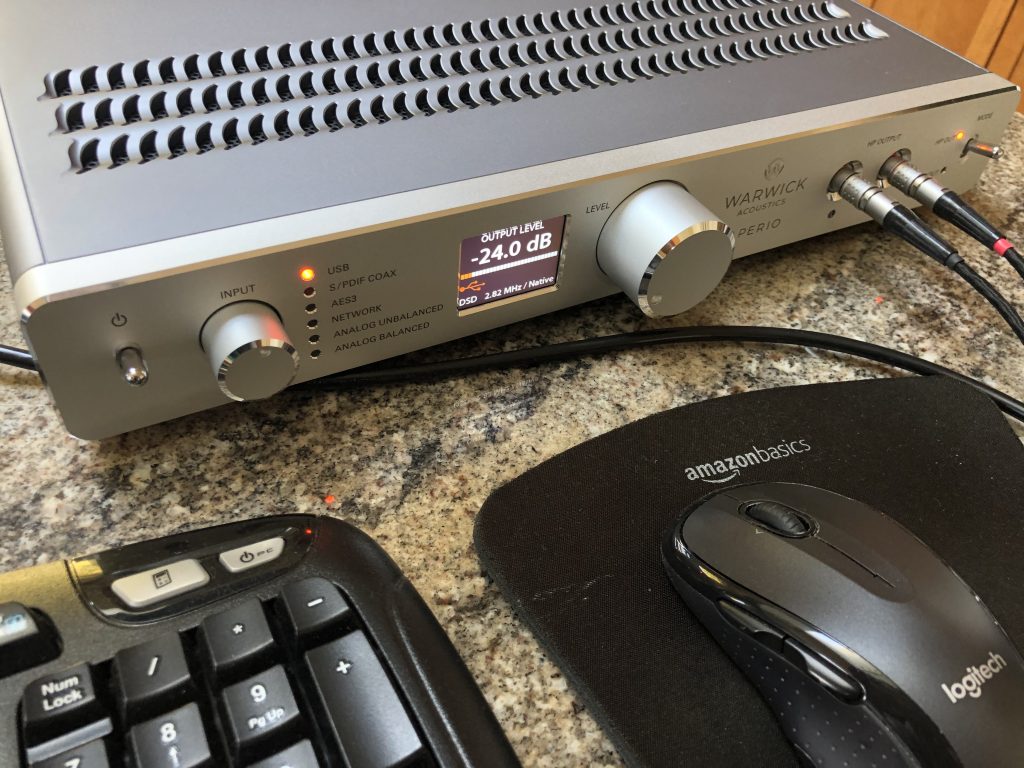

The Vivid Audio Giya G1 Spirit Loudspeakers with YG Acoustics Rack, Gold Note P-1000 MKII Preamplifier (top shelf), Gold Note Tube-1012 Tubed Output Stage (second shelf), Wolf Audio Systems Alpha 3 SX Music Server (third shelf), Innuos PhoenixNET Ethernet Switch. A pair of Audionet Heisenberg Monoblock Amps are on either side of the rack; my Walker Audio Master Reference turntable system is behind; all main system cabling is Kubala-Sosna Realization.

ELECTRONICS...UPSTREAM COMPONENTS

The extraordinary Audionet Stern reference preamp (image courtesy of Audionet)

Beauty and The Beast: A pair of the Audionet Heisenberg Reference Monoblock Amplifiers! (Image courtesy of Audionet)

Pass Labs' world-class Xs Reference Preamp on its Synergistic Research Tranquility Base UEF upon a Critical Mass Rack

The Merrill Audio MASTER TRIDENT Tape Head Preamplifier (image courtesy of Merrill Audio)

Audionet Pam G2 reference phono preamplifier with EPX power supply; Walker Audio Procession Reference Phono Amplifier (updated 2015).

On the other side of the listening room, the Audionet PAM G2 Reference Phono Amplifier, powered by the Audionet EPX Reference Power Supply.

SOURCES

The Mara MCI JH-110 Professional 1/4" half-track 7.5/15/30 IPS reel-to-reel recorder with custom dual Flux Magnetics playback heads for both internal and external tape head amplification

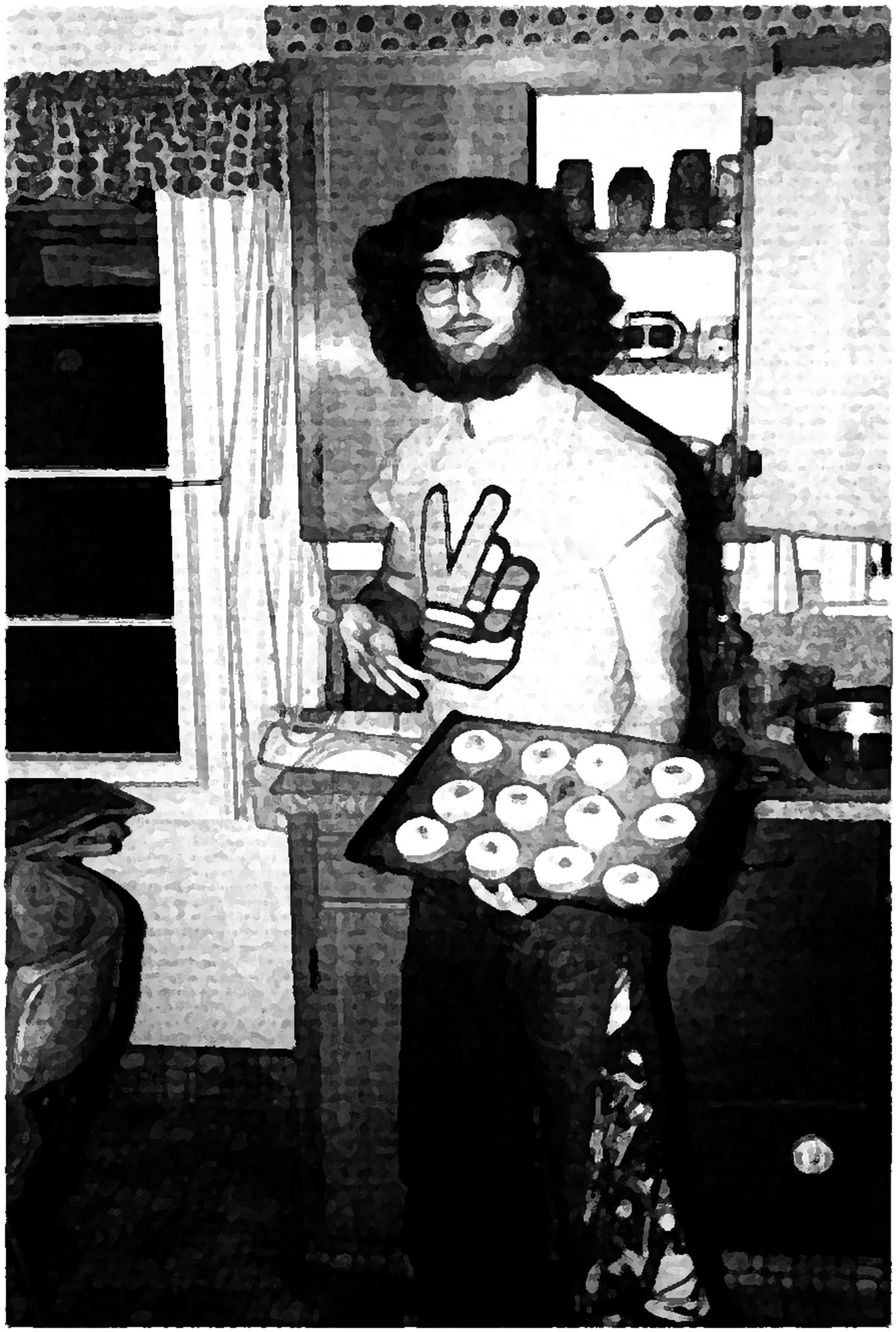

Lila Ritsema, Business Manager at Positive Feedback, accepts delivery of the Mara MCI Professional RTR recorder; our very experienced team from Priestley and Sons (Robert Vic, Zach Secreto, and Dustin Randall) prepares to move the 250 lb. beast to its new space

The Dohmann Audio Helix Two Turntable with Schroder CB-11 12" Tonearm and Phasemation PP-2000 Reference MC cartridge on Black Diamond Racing carbon fiber shelf, resting on Stillpoints ESS Grid Rack.

A beast of a beauty: the LampizatOr Vinyl Phono MC-2 Silver Phono Amp...all tubes!

To die for!

And speaking of beastly beauty: The Gold Note PH-1000 Reference Phono Amp...the glory of Italian audiophile design! (Image courtesy of Gold Note.)

The DS Audio ION 001 Vinyl Ionizer with the Wave Kinetics NVS Reference Turntable (now returned)

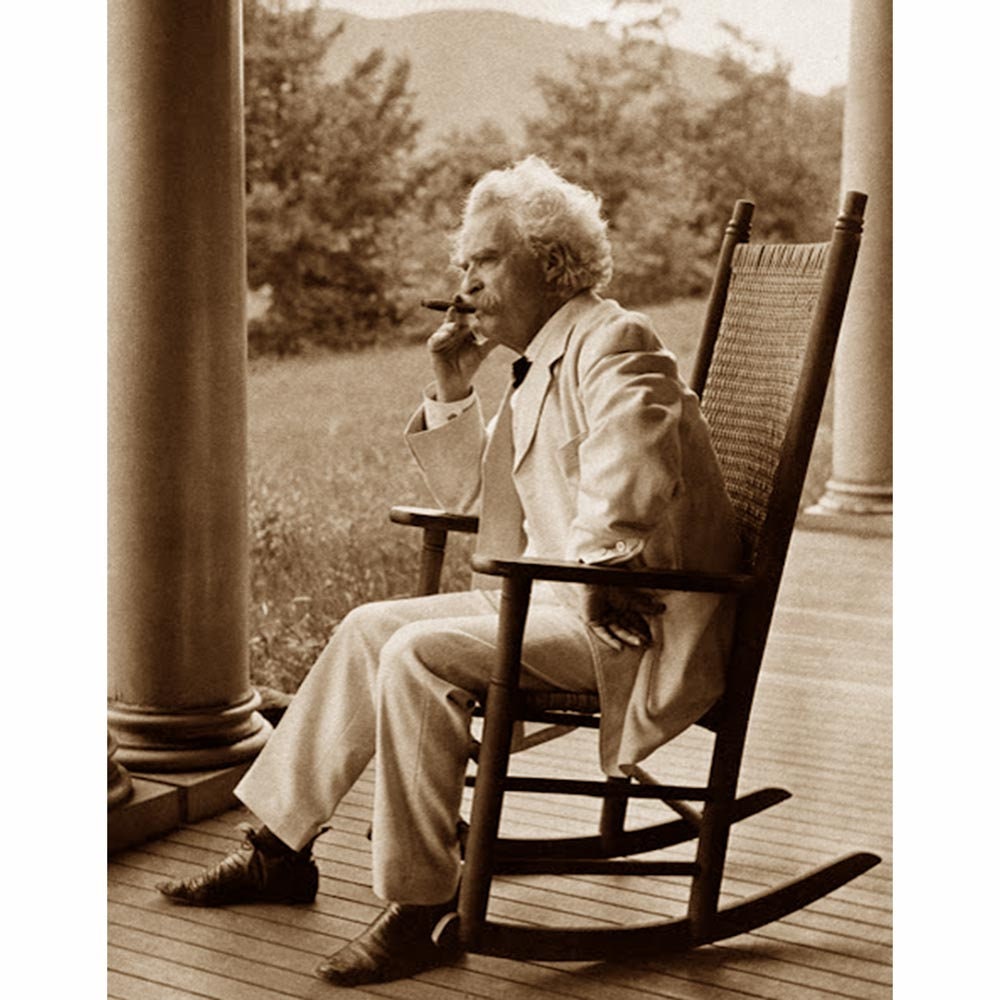

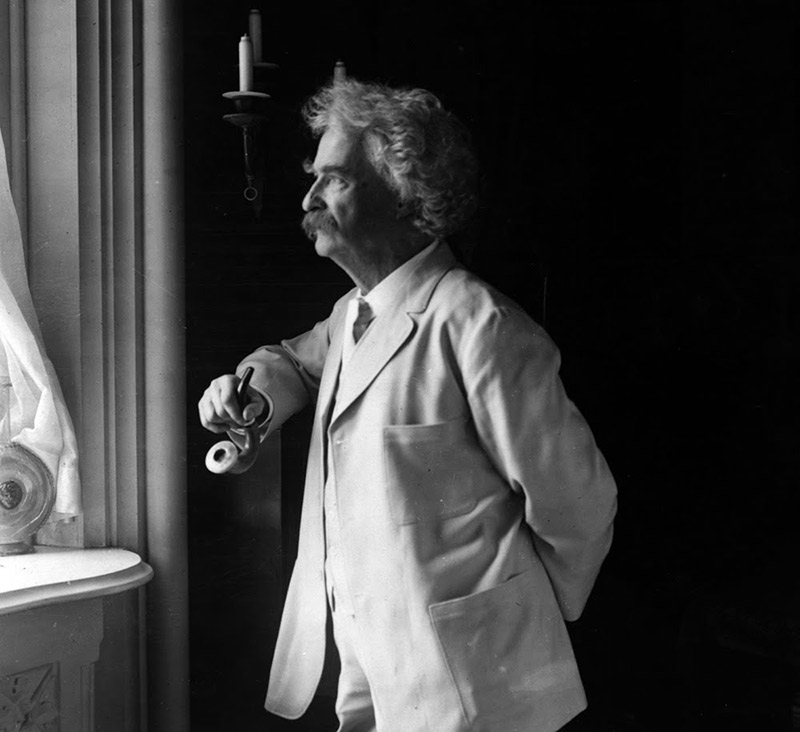

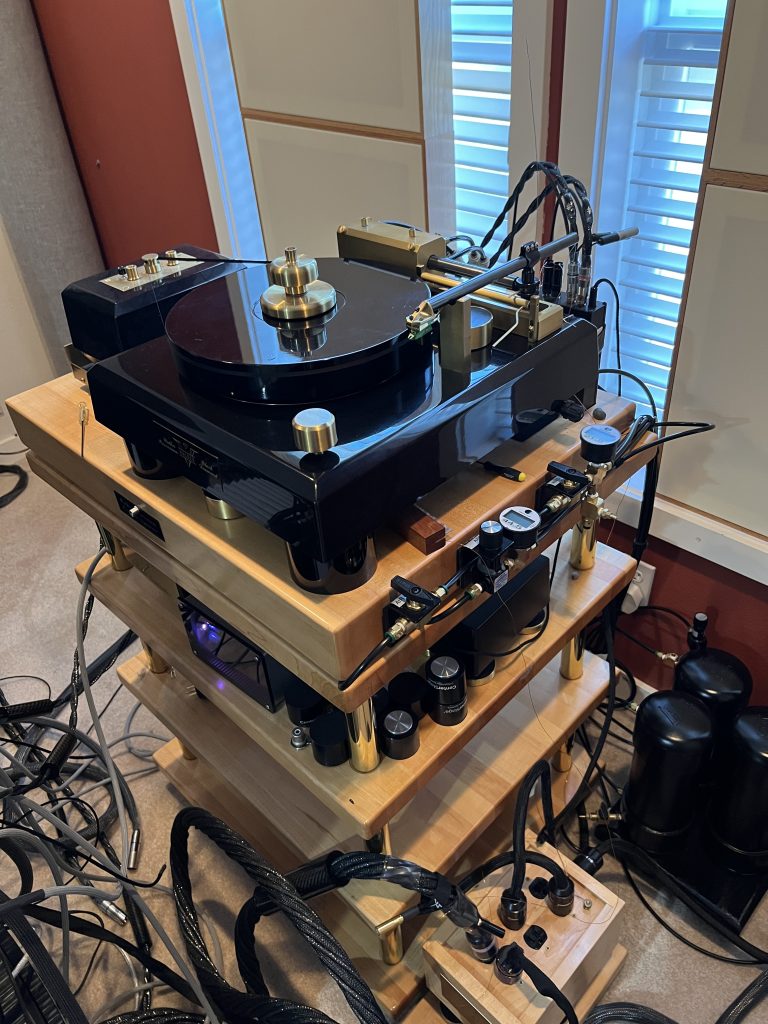

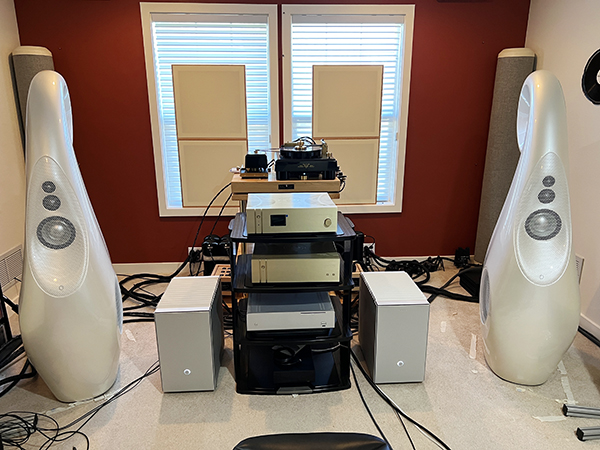

Analog: Dohmann Audio Helix Two reference turnable, with Schroder BM-11 tonearm and Phasemation PP2000 MC cartridge, with Cardas Audio Clear Beyond XL Interconnects; Walker Audio Proscenium Black Diamond Master Reference Turntable System, complete with new air pump system, Master Reference rebuild by Fred Law, including turntable pressure and pressure control system. Equipped with Procession Phono Amp and Prologue Rack System, and latest motor control and crystal technology in the platter, with Soundsmith Hyperion II MI Cartridge.

Lloyd Walker's exceptional Walker Audio Proscenium Black Diamond Master Reference Turntable on its Prologue Rack, with Peter Ledermann's Soundsmith Hyperion II MI Cartridge. The Proscenium Black Diamond Master Reference was upgraded May 27-29, 2022 by Fred Law. In memoriam of our dear audio friend and master turntable designer, Lloyd Walker.

Peter Ledermann's brilliant Hyperion II MI cartridge. Custom made, and killer!

The new Walker Audio Proscenium Air Supply System...a major development (installed May 27-29, 2022).

The Playback Designs MPT-8 Reference SACD/CD Transport

The Playback Designs MPD-8 DAC with Stream-X Roon-ready Internet streaming

Playback Designs MPT-8 Reference Transport on its Synergistic Research Tranquility Base UEF active (above) and the Aurender A30 Music Server with 10TB storage/DSD512 DAC/Streamer with MQA and Tidal/Qobuz support/Teac Esoteric CD Ripper/Headphone Amp/Volume Control functions/IOS and Android Conductor App for remote control. Both are supported by the Stillpoints ESS Grid Rack system. Four greats in one place!

The Aurender A30 Reference Streamer/Music Server/DAC/CD Ripper/Headphone Amp

Aurender's brilliant N20 Caching Music Server/Streamer (image courtesy of Aurender)

The Aurender A30 in action on its Stillpoints ESS Grid Rack: playing Jethro Tull's Stand Up album in MQA Master 96kHz/24-bit resolution

The iFi Pro iDSD Signature DSD1024 DAC/Streamer/Amp (image courtesy of iFi)

The iFi Pro iDSD DSD1024 DAC/Streamer/Amp, rear view (image courtesy of iFi)

The iFi Neo Network Audio Streamer...amazing!

The exaSound Delta Music Server with its touch screen display panel. This exaSound Delta Music Server is configured with i9 9900 processor, 32 GB RAM, and 2 TB SSD; iFi Pro iDSD DSD1024-capable DAC.

Aurender A30 Reference Streamer/Music Server/DAC/CD Ripper/Headphone Amp; Playback Designs MPT-8 SACD/CD Reference Player and MPD-8 Quad DSD DAC with Stream-X option; LampizatOr Pacific 8x DSD/PCM DAC; Playback Designs Merlot Quad DSD DAC, Pinot Quad DSD ADC, and Syrah Quad DSD Music Server, with Oppo BDP-103 optical transport with Opbox optical converter for PLINK connection to Playback Designs devices; Mytek Digital Manhattan II DAC/Preamp/Streamer with Streaming and Phono options; Mytek Digital Brooklyn DAC+ DAC/Headphone Amp/Preamp; Mytek Digital Liberty DAC DAC/Headphone Amp; Mytek Brooklyn ADC; Merging Technologies NADAC 8-channel Quad DSD and PCM DAC with Power+ separate power supply (completely upgraded 03/2018); exaSound e68 8-channel Quad DSD/PCM DAC with Pardo Power Supply; exaSound e62 Mk II stereo Quad DSD DAC with MQA and Pardo Power Supply; Furutech STRATOS Quad DSD DAC; Marantz UD9004 Blu Ray/Universal Player; Korg MR-2000S Double DSD-capable digital recorder.

The outstanding Merging Technologies NADAC MC-8 Power+ two-box Ethernet-based eight-channel Quad DSD DAC on the Stillpoints ESS Reference Rack with Grid Shelves on the Stillpoints Ultra 5 Isolation Feet. Upgraded 02/19/18 to POWER+ separate power supply.

The magnificent LampizatOr Pacific Directly-Heated Triode 8x DSD (DSD512) DAC upon its arrival here.

The utterly seductive MESH 45 Directly-Heated SET Tube.

Analog: Walker Audio Proscenium Black Diamond Master Reference turntable system (upgraded 05/2022) with the Black Diamond Arm, Soundsmith Hyperion MI cartridge, and Silent Source Silver direct connection to the new Walker Audio Procession Reference Phono Amp and the new updated Master Reference air supply and crystals for the turntable; MARA MCI JH-110 Professional RTR system with two brand new custom Flux Magnetics playback heads; Pioneer RT-707 7.5 ips quarter track reel-to-reel tape recorder, Nakamichi Dragon reference cassette deck.

HEADPHONES/IN-EAR MONITORS

The T+A Solitaire 6 Open Planar Headphones (image courtesy of T+A)

T+A Solitaire P Open Planar Headphones; Grado Labs Hemp Headphones; Dan Clark Audio Stealth headphones; Focal Utopia Reference Headphones; Sendy Audio Peacock headphones; Grado LAOC 25th Anniversary custom balanced headphones; Dan Clark Audio VOCE Reference Electrostatic Headphones; ESS 422H Heil Headphones; ESS 252 Headphones; JPS Labs Abyss AB-1266 Reference Headphones; Audeze LCD-4 Revision 2 Reference Headphones with Audeze balanced and unbalanced cables, Audeze LCD-i4 and iSine 20 In-Ear Headphones; cables by Double Helix (Prion4 balanced and single-ended) and Nordost (Helmdall 2 balanced, single-ended, and 3.5mm); Oppo PM-1 Headphones; Sennheiser HD800 Reference Headphones (balanced) with Cardas Clear Headphone Cable (2 meter), Cardas Sennheiser connectors, and Cardas Balanced connectors, Cardas Clear Balanced-to-1/4" stereo jack adapter, Double Helix Cables Complement3 balanced and single-ended cables, Blue Microphones Ella Powered Headphones, JH Audio JH16 Pro In-Ear Monitor System, Cardas 5813 In-Ear Monitors.

HEADPHONE AMPS/DACS

The T+A HA-200 Headphone Amp

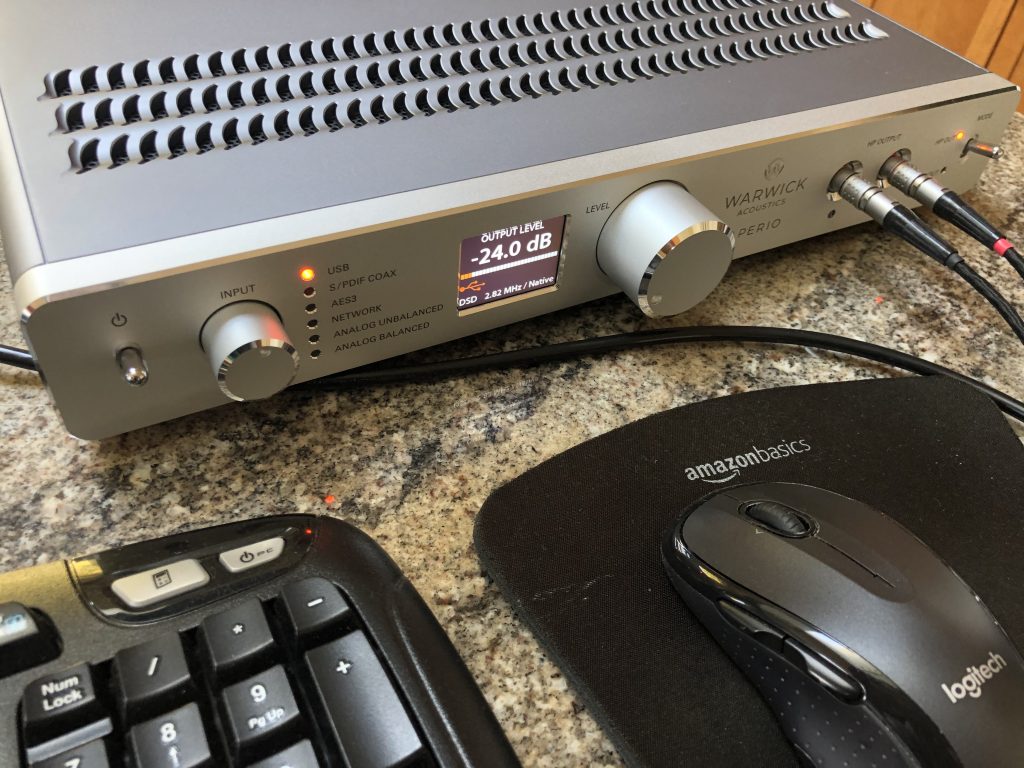

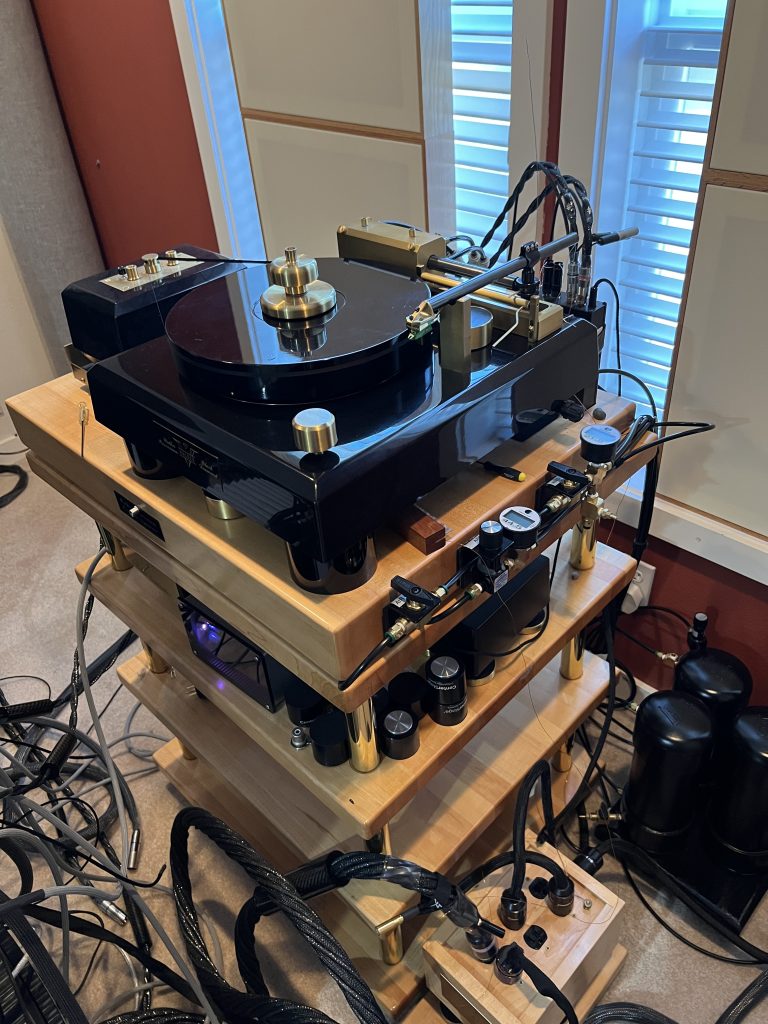

The Warwick Acoustics Aperio Professional Reference Headphone Amp and BDEL Reference Headphones

The HeadAmp Blue Hawaii Reference Electrostatic Headphone Amplifier with stock tubes (upgraded to NOS EL-34 tubes); image courtesy of HeadAmp.

The HeadAmp GS-X Mk II Reference Dynamic/Planar Headphone Amplifier

PASS Labs HPA-1 Headphone Amplifier

T+A HA 200 Reference Headphone Amp; Warwick Acoustics Aperio Reference DAC/Headphone Amp/BDEL Headphone system; HeadAmp Blue Hawaii two-box reference tube (EL-34) headphone amplifier for electrostatic headphones with NOS Siemens EL-34 tubes supplied by RAMTubes; the HeadAmp GS-X Mk II two-box Reference Dynamic/Planar Headphone Amplifier; PASS Labs HPA-1 Headphone Amplifier; Furutech STRATOS DAC/Headphone Amp/A-to-D with Furutech GT2 Pro-2B USB cable; eXemplar audio eXception Reference Headphone Amp, upgraded edition (as of August, 2017)...

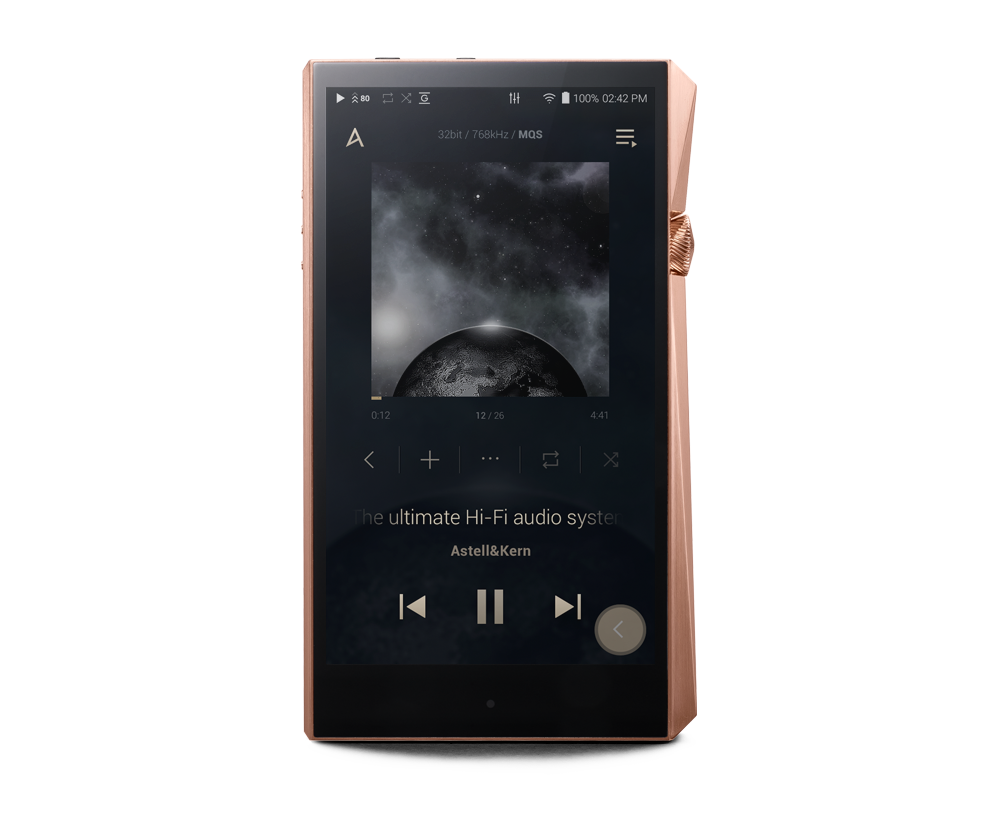

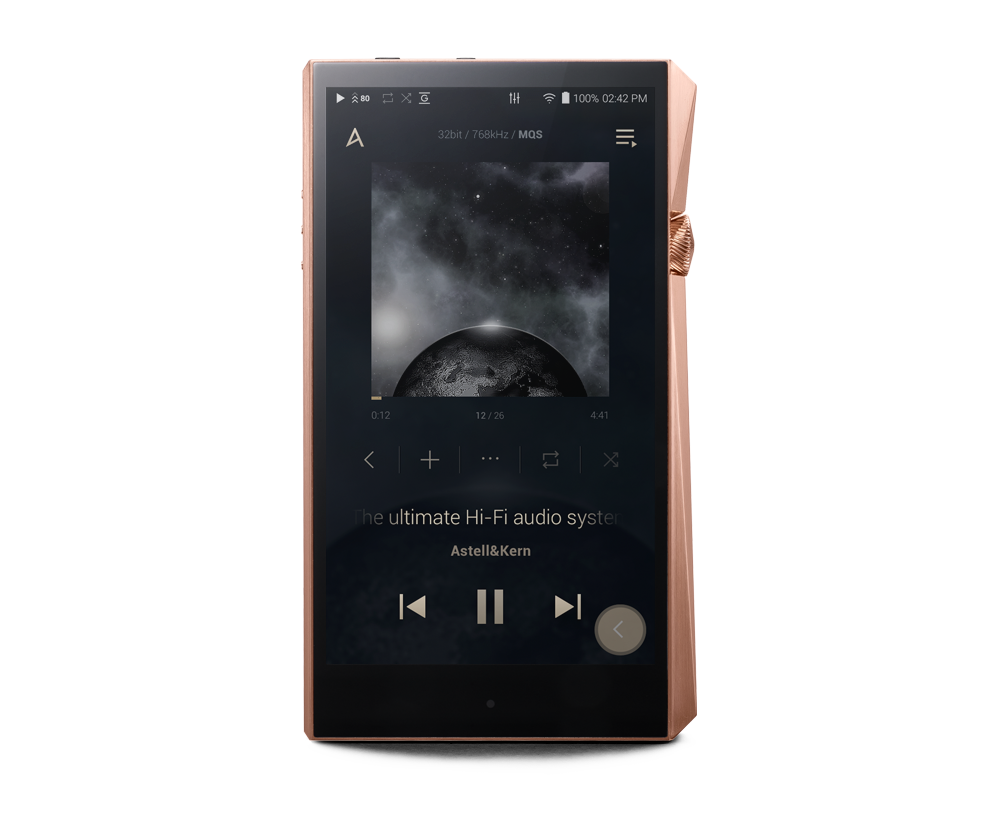

The Astell & Kern A&ultima SP2000 Reference Portable Audio Player, with streaming media (image courtesy of Astell & Kern)

...Astell & Kern A&ultima SP2000 DSD512/MQA Portable Reference Player/Headphone Amp with DSD512 in Native Mode and up to 768kHz PCM; Astell & Kern CD-Ripper; ALO Studio Six reference tubed headphone amplifier; ALO Audio Continental DSD DAC and headphone amp; Aurender FLOW DSD DAC and headphone amp;Ray Samuels SR-71B portable headphone amplifier (balanced and unbalanced connections).

CABLES

Interconnects by Cardas Audio, Kubala-Sosna Research, TARA Labs, Skogrand Cables, Synergistic Research (latest generation reference cables, 2022), JENA Labs, Silent Source, Evolution Acoustics, Harmonic Technology, Stereovox, Black Cat, Esperanto Audio, and Linn. Speaker cables by Kubala-Sosna Research, TARA Labs, Skogrand Cables, JENA Labs, Cardas, Silent Source, and Linn. Power cables by Purist Audio, Kubala-Sosna Research, TARA Labs, Skogrand, Furutech, JENA Labs, Cardas, Evolution Acoustics, First Impression Music, and Silent Source.

ACCESSORIES

The Kubala-Sosna XPander Power Distribution Unit (image courtesy of Kubala-Sosna)

Sui generis: The GamuT Lobster Chair for reference-grade audiophile listening and evaluations. Deep Zone Meditative Listening, for sure! (Image courtesy of GamuT Audio)

The Add-Powr Sorcer X4 AC Power Harmonic Resonator; Critical Mass Systems QXK Rack System and QXK Amp Stand; Synergistic Research PowerCell SX Power Distribution system with Synergistic Research SX Power Cable and MiG SX Isolation Devices; Synergistic Research system enhancements, including Atmosphere FEQ Carbon, Infinity, XL4, and Standard with ATM, 2 Tranquility Base electronic isolation bases, HFT's, MiG 2.0 isolation feet with HFT, Active Ground Block SE, and Black Box; DS Audio ION 001 Constant Ionizing Device for LPs; van den Hul The Extender sonic space enhancers; three Stillpoints ESS Racks with grid shelves and Ultra 5 isolation feet; Walker Audio Prologue Rack, Walker Audio Prologue Turntable Stand, Walker Audio Prologue Amplifier Stands, Walker Audio Valid Points and Valid Points tuning kits, two Walker Audio Velocitor Mk. V Power Line Enhancers on Velocitor Stands, one Walker Audio Velocitor Mk. V Power Line Enhancer on a Velocitor Stand (line conditioning for Walker Audio Proscenium turntable system); KLaudio CD-CLN-LP 200 Ultrasonic LP Cleaner with Silencer sonic enclosure, KLAudio Automatic Record Loader for their Ultrasonic LP Cleaner, with 7" and 10" record adapters; Furutech Demaga LP/SACD/CD/Blu Ray/DVD/cable demagnetizer; Furutech DF-2 LP flattener, Vibraplane turntable isolation platform, Black Diamond Racing "The Shelf" and cones, Dedicated Audio Cable Tower cable supports, VPI 17F LP cleaning system with the latest Walker Prelude Record Cleaning System (11/2011 edition), Walker Audio Extreme SST Contact Enhancer (2011), Walker Audio Ultra Vivid SACD/DVD/CD enhancer (improved formulation, 06/2009), Walker Audio Talisman LP/disc De-static device, Furutech DeStat II static neutralizer, Furutech RD-2 SACD/DVD/CD demagnetizer, Stein Music DE-2 CD/SACD degausser and DE-3 LP Conditioner, Furutech DeMag LP/SACD/DVD/CD degausser, Furutech SK-II Electrostatic Brush, Audioquest Anti-Static Record Cleaning Brush, Cen-Tech Analog Sound Level Meter, KAB Speed Strobe turntable strobe measurement system, acoustical treatments by Walker Audio, ASC and NuCore, Kubala-Sosna XPander Power Distribution Unit, Walker Audio Black Diamond Room Tuning Crystals kit.

The KLAudio KD-CLN-LP200 Ultrasonic Record Cleaner with its LP Loader option, automatically cleaning up to 5 LPs at a time.

My listening room is of irregular shape, being 12.5' wide x 13.5' long in the right section, and 18' long in the left (equipment) section, with a ceiling height of 8'. It is cambered left and right, with no perpendicular edge on the sidewalls to ceiling transition. Construction was done with 2" x 6" studs, wall-within-a-wall on the left and right sides (media storage in a room to the left, equipment storage in a room to the right). The room is on the second floor, directly over the garage—no competing sounds. The neighborhood is quiet, being located on top of a hill some 500 feet above the valley below, the listening room faces south, away from the main access road. I've measured the room's noise floor using the AudioTools app with my iPhone 6+ at 30dB, a very good number for the "real world." In other words, pretty bloody quiet.

Power to components in the listening room is fully dedicated. 10 gauge Romex was pulled directly from the panel, all from the same pole to avoid ground loops. Four 20 amplifier runs were done, and Tesla Flex and JENA Labs cryo-treated AC receptacles were installed. All lights and peripheral components are on separate circuits. Circuits have been tested for proper ground and polarity.

Robinson's Home Theater/Surround Sound System

Linn Kisto Reference Surround/Stereo Controller (x2)

Linn 5125 5.1 channel amplifiers (x 2, 5 channel bi-amped configuration)

Linn Akurate 242 L/R front channel speakers

Linn Akurate 225 center channel speaker

Linn Akurate 212 L/R rear channel speakers

Synergistic Research Atmosphere FEQ Carbon and XL4 with ATM, HFT's, MiG 2.0 isolation feet with HFT, Grounding Block, and Black Box

Cisco SG 300-20 (SRW2016-K9-NA) 20-Port Gigabit Managed Switch (Surround Room)

Cisco SG 300-20 (SRW2016-K9-NA) 20-Port Gigabit Managed Switch (Office Infrastructure)

Cisco SG 350-10 (SG35010-K9-NA) 10-Port Gigabit Managed Switch (Secondary)

Sony HAP Z1ES Double DSD Music Server with Xperia Pad remote control

Paradigm SUB 25 reference subwoofer

All HDMI cables by Furutech, including their HDMI-N1-4 4K HDMI cable

Sony XBR-65A1E 65" OLED 4K Ultra HD TV with HDR

Furutech Daytona 303 AC Line Filter (two units)

Furutech 20 amplifier duplex AC receptacles (two duplex units)

Cables by Furutech, Cardas, Linn, JENA Labs, and EMM Labs

Oppo BDP-205 4K Ultra HD Audiophile Blu Ray Disc Player

Oppo Digital BDP-203 4k/Blu Ray Disc Player

exaSound e68 8-channel Quad DSD DAC with Pardo external power supply

Xfinity X1 Cable TV Controller with DVR, 4K support, and multi-room capability

Amazon Fire 2nd generation video/audio streaming unit, with 4K support

Apple TV (Fourth Generation with 4K support, 32 GB)

Ansuz PowerSwitch D2 Ethernet switches (one upstairs, one downstairs) with Sortz Noise Suppressors, Darkz Resonance Contollers, and Mainz D2 AC Power Cables

The home theater system is housed in our great room. The dimensions are 18' wide by 24' long, with a peaked and vaulted ceiling that's 16' high at the center of the lengthwise room line. The fireplace forces a "shift left" of the High Definition TV and the L/C/R playback, a necessary compromise that skews the sound somewhat, but still allows for a satisfying home theater/surround sound experience.

The Vinnie Rossi L2i SE Integrated Hybrid Amplifier with optional DAC and Phono Amp sections

Robinson's Reference Desktop/Computer-based/Internet-based Music System

Home Network is 1.0 gigabit for maximum Internet performance via Xfinity/Comcast

Dell Precision T7920 workstation, Windows 10 Professional, Blu Ray R/W and DVD R/W optical drive, NVidia High Definition audio, dual Intel Xeon Silver 8-core processors, 64 GB ECC RAM, 4 TB RAID 1 hard drive array with multiple external 3, 4, 5, and 8 TB USB 3.x hard drives

Dell Precision T7600 workstation, Windows 10, Blu Ray R/W and DVD R/W optical drive, Realtek 192kHz PCM audio, dual Intel Xeon 6-core processors, 64 GB ECC RAM, 3 TB RAID 1 hard drive array with multiple external 3, 4, and 5 TB USB 3.0 hard drives

HP Pavilion DV8t notebook computer, Windows 10, nVidia+Altec Lansing Sound, Intel i7 processor, 8 GB RAM, 480 GB Solid-State Drive (SSD), 18.4" 16x9 display supporting 1080p (true Blu Ray), Blu Ray R/W, DVD+/-RW, and CD-RW

Playback Designs IPS-3 integrated amplifier with Quad DSD DAC

The beautiful and revealing Focal Sopra 1 2-way Monitor Loudspeakers and dedicated stands...not going away! (Image courtesy of Focal Naim America)

Focal Sopra One Monitor Loudspeakers

GamuT Phi3-i Monitor Loudspeakers

Evolution Acoustics Micro One loudspeakers with Wave Kinetics isolation feet

Audioengine A2+ Powered Desktop Speakers with Wireless Support

exaSound DM reference-level Network Audio Player and Quad DSD DAC

exaSound e62 Mk II DSD512/PCM/MQA DAC with Pardo Power Supply

exaSound PlayPoint Network Audio Player with Pardo Power Supply

Headamp Blue Hawaii Tubed (EL-34) Reference Electrostatic Headphone Amplifier

RAM Tube Works NOS EL-34 tubes for tube-rolling the Blue Hawaii

Warwick Acoustics Aperio Reference Headphone Amp/DAC with Aperio BD-HPEL Reference Headphones

Oppo BDP-105 Universal Player with ModWright Tube Modification with Custom MWI Reference and Truth power cable, Power Supply 9.9 with custom large tube chassis opening and Phillips 5R4GYS rectifier tube upgrade, dual Bybee Rail mods, and Audio Magic Pulse Gen ZX.

Teac Esoteric DV-60 Universal Player (used mainly for SACD)

CLONES AUDIO SG110D-08 MOD modified Cisco 8-port Ethernet switch for audio, with femto clocking

Dell 1500 VAC Monitored UPS

Three (3) APC 1500 VAC Battery Backup/Line Conditioner Units

Robinson's Outdoor Music System

Mytek Brooklyn+ Amp

exaSound PlayPoint Network Audio Player and Streamer with Roon, Qobuz Studio, and Tidal Master

exaSound e62 Stereo DSD512/MQA DAC

exaSound e68 8-channel DSD512/two-channel DSD512

Ansuz PowerSwitch D2 Ethernet switch with Sortz Noise Suppressors, Darkz Resonance Contollers, and Mainz D2 AC Power Cable

Focal 100 OD8 Outdoor Loudspeakers

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs and image processing by David W. Robinson, copyright (c) 2023, all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated. None of my photographs may be used or republished in any way without my prior written permission.