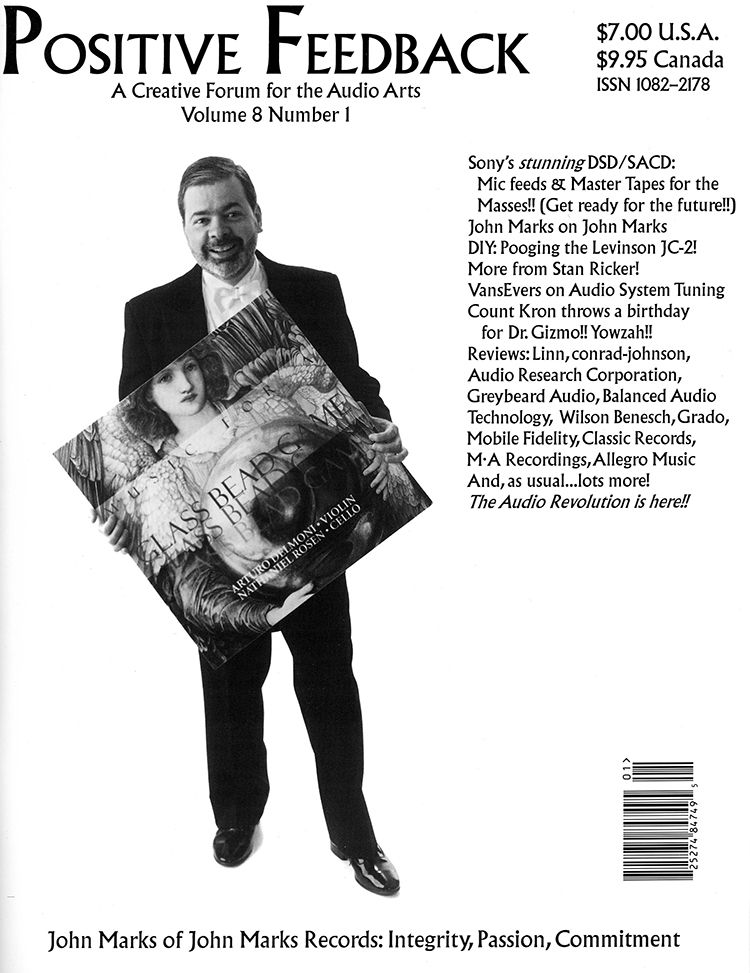

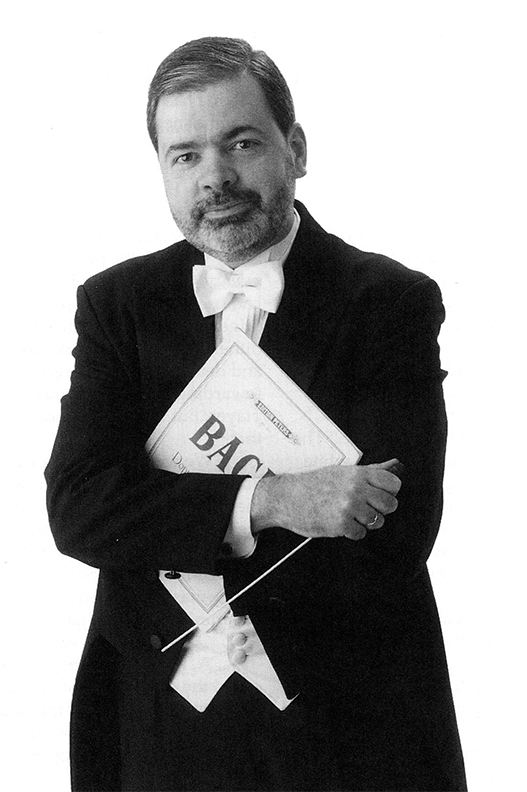

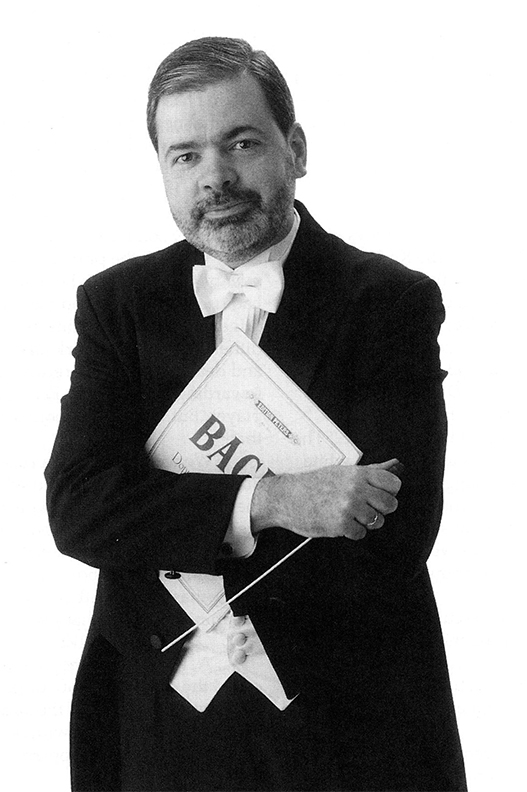

A gift, a sudden gift from audio compadre John Marks, proprietor of The Tannhauser Gate blog site. John is also the driving force behind John Marks Records, which was active in the 1990s but is now lamentably no longer producing recordings. His work moved me so much that he was featured on the cover of one of the issues of Positive Feedback back in our paper-and-ink days.

This in the days of his very fine album, Glass Bead Game. I still have my copy of the CD.

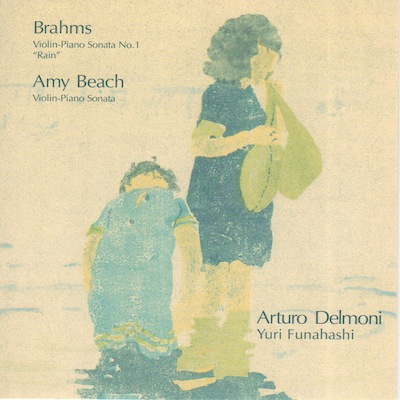

Now John shares with us another of his recordings, favoring us with a collection of tracks below from Arturo Delmoni and Yuri Funahashi. Many thanks to John for his generosity, and for the delight of these performances, wonderfully recorded.

Enjoy!

Dr. David W. Robinson, Ye Olde Editor

Tuesday, September 5, 2017 is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Amy Marcy Cheney Beach (September 5, 1867 – December 27, 1944). To quote Wiki: "She was the first successful American female composer of large-scale art music, breaking a glass ceiling when her ‘Gaelic' Symphony was performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1896."

Arturo Delmoni asked me to upload not just sound bites but instead his and Yuri Funahashi's entire recorded performance (from CD JMR 2, which a third-party seller on Amazon would like you to pay $1526.83 for a new copy of—but there is a bottom-feeding underbidder asking only $166.99; such are the values of my back catalog on the crazy collector market).

As you'll see below, there are: a photo of Mrs. H.H.A. Beach (as she wished to be known); m4a embeds of all four movements of her Sonata in A minor, Op. 34; and the relevant section of my liner-note essay.

Happy Birthday, Mrs. Beach!

Amy Beach (George Grantham Bain Collection, United States Library of Congress)

1 Amy Beach Sonata in A minor: I: Allegro moderato (part 1)

2 Amy Beach Sonata in A minor: I: Allegro moderato (part 2)

3 Amy Beach Sonata in A minor: II: Scherzo—molto vivace (complete)

4 Amy Beach Sonata in A minor: III: Largo con dolore (part 1)

5 Amy Beach Sonata in A minor: III: Largo con dolore (part 2)

6 Amy Beach Sonata in A minor: IV: Allegro con fuoco (part 1)

7 Amy Beach Sonata in A minor: IV: Allegro con fuoco (part 2)

John Marks' Original Liner Notes to CD JMR 2 (excerpt)

That Amy Marcy Cheney (Mrs. H.H.A.) Beach's violin sonata, as well as the rest of her music, is not better known, is a cause for speculation, if not outright conclusion jumping. However, to jump to the conclusion that Amy Beach's obscurity is a result of her gender is to disregard the historical facts.

Amy Cheney was born on a farm in New Hampshire. At a very early age (two), she harmonized whatever her mother sang to her, and soon thereafter could play it on the piano. Her parents did not exploit her as a child prodigy, instead arranging for her to study in Boston and later Germany. She made her debut with the Boston Symphony playing the Chopin F-minor piano concerto. The same orchestra later performed her "Gaelic" symphony, the first symphony by an American woman, and the first American symphony to quote folk themes.

Why then, is her name almost unknown to today's concert-goers? There are several reasons which singly or in combination may have contributed to Mrs. Beach's current obscurity. First, she wrote tonal, melodic music in traditional forms. As surprising as this may seem as a reason for obscurity, it makes some sense.

Amy Beach wrote in a musical tradition that, by the 1920s, was perceived to be a thing of the past. This was especially so after the horrors of World War I, and the resultant anti-Edwardian reaction that nearly relegated Elgar to a similar degree of obscurity. Beach did not write "new" music, as did Stravinsky. Beach's music had no champions in the conservatories, either here or abroad. Although her symphonies were performed in Europe, no European orchestras made them their own. Not coming from Europe herself, as did Dvorak and Tchaikovsky, her music had less cachet with American audiences. Also, Beach did not have to go on tour to make a living or support a family, as did Brahms and Dvorak.

Although she was well respected by her contemporaries and well-represented in books and journals of the day, the popularity of Beach's art did not withstand the advent of musical modernism. From the time of her death until the early 1970s, Beach's music was as good as forgotten. Renewed interest in female composers coincided with the 1976 bicentennial of the American Revolution, which brought renewed interest in American composers in general. However, Amy Beach's music is still perhaps more written about than actually heard.

To speculate about the reasons for its obscurity is natural, because Amy Beach's violin sonata is a wonderfully complex, assertive yet introspective, exhilarating work, worthy of almost any major late-Nineteenth century composer. It is a masterwork that will reward even casual listening, and deserves much more currency.

Beach wrote this sonata in 1896, when she was 29 years old. She gave its premiere with Franz Kneisel in 1897. There is an undeniably ripe, fin-de-siecle voluptuousness to the shape of Beach's melodies. Her writing reveals shadings of Wagnerian chromaticism and Impressionist harmonies, all in the service of genuine and powerful emotion. Beach's handling of the instruments and the balance between them is deft, and her youthful, exuberant self-confidence is demonstrated by the insouciant quasi-academic fugue that pops up in the last movement.

(end)

Arturo Delmoni's and Yuri Funahashi's CD with the Beach Sonata as well as Brahms' first violin-piano sonata (one of Delmoni's truly outstanding performances) is available as a just-in-time replicated CDR from ArkivMusic.