|

|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 66

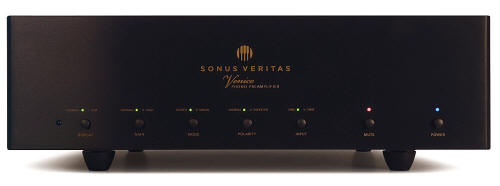

sonus veritus Genoa Preamplifier as reviewed by Marshall Nack

Listening to the Genoa Preamp from Sonus Veritas is sooo relaxing, kinda like taking a day off and going to the spa. Not that that's my habit—I've never been to a spa—it's the newly introduced warmth and liquidity that conjures the association. But was the Genoa excessively so? Anytime a product elicits such a "feel good" response, my antennae go up and start to quiver, like Ray Walston in that '60s sitcom "My Favorite Martian." This question stayed with me for the first two weeks 'til I got tired of asking it. I decided the Genoa is more like a dry shower (if you can imagine that).

Some Background First, a word or two about the company and the designer. Sonus Veritas was founded in 2009 by two audio enthusiasts, Joe Rosovitz (President) and Kevin Carter (VP and Chief Engineering Officer) as a manufacturer of no-holds-barred components targeting the upper end of the market. The idea of a true differential balanced preamp had been percolating in Kevin's mind for a long time. In 1996, he created his first conceptual model. Five circuit board revisions and 17 years later, along with the formation of a new company, the product has arrived. the Sound It took some time to get a reading on this preamp. First impressions were a mixed bag. With average CDs the Genoa was a little underwhelming. Not that there were particular issues—everything was done well, just not up to what I expected for a component at this price point (MSRP $16,000). If you are primarily interested in the audiophile commodities like resolution, dynamics, transient speed—there are better product offerings. The Luxman C-800f, currently under review (MSRP $19,000), has some of the Genoa's warmth, but more resolution. The transient on my mbl 6010D (MSRP $26,500) is faster and hits with more impact. The mbl resolves deeper. Decay trails are seen as separate events—not that they last longer, just that they are distinct from the note itself. For truly SOTA performance, nothing I've encountered offers the Soulution 721preamp's penetrating level of resolution, which is like upgrading to HDTV. (We're well up into the ultra-luxury class with this one, MSRP $40,000.)

But when I put on better quality source material, especially some of the audiophile reissue LPs, the Genoa scales to some of the best sound ever at Nack Labs. Great vinyl, like Lalo—Symphonie Espagnole, with Leonid Kogan (Testament heavyweight reissue of SAX 2329), was the stuff vinyl dreams are made from. On this LP from 1960, everything came together: the orchestra and soloist are in top technical form; the conductor and the soloist are in sync (so often a performance is ruined when interpretations differ); and the engineers got lucky and caught the moment. This reading is dramatic—it'll keep you on the edge of your seat. What a food chain: the Dr. Feickert Firebird turntable feeding the Allnic H-3000V phono stage, then the Genoa line stage! (BTW, in case you go looking on the internet, original SAX pressings of this EMI LP go for over a grand. Even the reissue goes for $70.) These mixed impressions recalled my time with the Venice Phono Stage, the first Sonus Veritas product I reviewed.

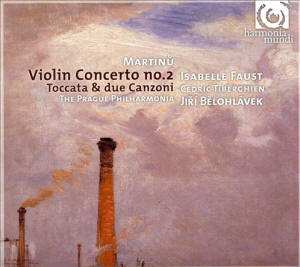

Yes, reading over that copy describes a similar scenario. Average goods could be less involving, but the Venice made my reference LPs sound glorious. Similarly, the Genoa does not resuscitate ordinary, equalized CDs—it doesn't put in what isn't there. But with a top-notch source, both products deliver excellent sonic goods. I attribute the mixed results to an uncommon degree of honesty in both. Voicing So, what is it that I find so seductive? Let's listen to Isabelle Faust performing the Bohuslav Martinu Violon Concerto No. 2 (HMX 2908454.55). Whatever it is that signals a live event is present in this recording.

The recording's engineering is a big factor. Unlike so many current concerto recordings, the soloist is placed in correct relationship to the orchestra, both in terms of loudness, image size and location. There is no hyping, or sense of behind-the-scenes, post-production tinkering. But it's what the Genoa does in the realm of timbre that separates it from the crowd. Violins have the credible materials of the real instrument—the wood, the strings and the body. When classical strings are done right, it always brings a smile. And this is true not just for the strings. Brass instruments have a jagged, edgy transient followed by a smooth, bell-like sustain; woodwinds sound reedy. The Genoa gives you as wide a variety of musical contrasts and timbral colors as you are likely to encounter. For many of us, this is priority number one. Perspectives Here's a second, related point along these lines. One of the first things savvy listeners look for in evaluating a component is consistency. Apart from a smooth and even frequency response, you want consistent quality. If the cellos sound woody, so should the violins. Low frequency instruments should not be reproduced radically different than mid and high ones. Nothing should stick out and become noticeable. One of the reasons I bought the mbl 6010D is because it does this so well. Its excellent consistency across the audio band helps it to sound less analytic and more musical than most solid-state preamps. Regardless of which band is activated, the sound is of a piece with what came before. This even-handed quality does wonders for frequency integration and coherency, the impression that everything is cut from the same cloth. This is one of the first things I listen for. Indeed, it is a virtue. But I've long been aware that this very quality imparts a degree of sameness from instrument to instrument. There are characteristics of the upper strings that I hear in the woodwinds, or the brass for that matter. While there's no difficulty identifying the various instruments of the orchestra, I'm aware of carryover regardless of which instrument is playing. This is the mbl's signature. Genoa Portrait The Genoa does the opposite: it makes every instrument sound unique. They all stand apart: they are all noticeable. Some people think this is spotlighting or less coherent. Make no mistake: the Genoa is coherent, just in a different way. Which approach is right? They both are. Mainly, it depends on where you sit and in which hall. Last night I was in the balcony of Carnegie Hall listening to the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra under Daniel Barenboim. It was one of those magical evenings. They had perfect ensemble and impeccable intonation—the 80 or so musicians on stage sounded like one huge instrument. For days I thought about how it reminded me of the mbl. But in a smaller hall, and especially when you're up close, you get the deeply saturated, highly variegated, distinctive timbres of the Genoa. Filling out the Portrait Let's go back to where we began. The Genoa tilts to the colorful side of neutral. Its sonic portraits are saturated, warm and liquid. Solid-state sterility and dryness are purged—forget about harshness, glare and brightness. It is grainless and noise-free. To some, this adds up to euphony; to most of my visitors, it was beguiling. Part of what makes the Genoa so ingratiating is its center of gravity—its tonal center is in the lower mid/upper bass range. When I replaced the 6010D, I had to lighten the tonal palette because the Genoa's so weighty. But, once accommodated, the Genoa has full bandwidth and is simply the weightiest preamp I've encountered. The treble is very fine: extended, sweet, grainless and smooth—in a word, exemplary. At the other end, mid-bass is a touch emphasized and a tad loose. Tech Discussion It's not just the presence of four 6N30P tubes that accounts for this voicing. In addition, the Genoa uses amorphous core Lundahl coupling transformers on the output side instead of capacitor coupling.

A third contribution harkens back to the true balanced design. True differential balanced design is common enough in solid-state components, but rare in the tube arena. Most tube components with balanced circuits employ two single-ended circuits of opposite polarity per channel. The issue here is common mode signals are amplified and passed on. A true balanced signal chain, like the one in the Genoa, has one differential circuit per channel and, very importantly, common mode signals are rejected. This decision alone accounts for a good portion of the Genoa's rich, full sonic palette and higher purity, according to the designer. Tube life in the preamp should be at least two thousand hours, so you can leave the Genoa on for long stretches without worry. The tubes are current production Sovtec. If you go looking, there are NOS 6N30P valves, but they are not recommended—Sonus Veritas explored NOS valves and found them highly microphonic.

Much of the circuitry in the Genoa is transplanted from the Venice Phono Stage, including the output stage, the transformers, the dual triode 6N30P tubes, and the power supply. Cosmetics and Features The rather large aircraft-grade aluminum chassis has a big footprint (18" w x 5" h x 15" d), although it looks small next to my mbl 6010D, and weighs 45 lbs. The matte black finish and cosmetics are conventional, the kind of matte black box that you might find from many manufacturers—Lamm Audio gear, for instance. Close inspection reveals superior fit-n-finish, as it should be at this price point. It is evident that care went into the chassis manufacture. Kevin doesn't go out of his way to damp the chassis other than using good-quality, good-sounding aluminum—the front and side walls are double thick layers of disparate aluminum alloy—but he does carefully select the four feet under the chassis. Cover the unused RCA jacks with Cardas or other brand of RCA caps. This quiets things down and helps the soundstage. Power conditioning is not required. There are individual toggle switches on the rear labeled Lift/Gnd, one for each individual RCA input and one for all of the outputs. Try the ground lifted setting first with your inputs. If there is no noise it should sound better. On the output side, if you are using balanced make sure the switch is set to Lift.

One nice to have: I wish there was a front panel display. When you're in the listening seat using the remote, you're guessing where the Volume is set or which Input is active. In operation, the units' top plate gets just slightly warm to the touch. Remote Control The optional universal remote can be used with their phono stage and DAC. Like the preamp itself, it is large and heavy. It is well-made—no, make that over-engineered. It is CNC milled from a billet of aluminum, but it is very big and not formed for the hand to hold easily. And it is too costly ($1,500).

Adjusting the analog volume control from the remote is a mechanical thing—each adjustment makes an audible click as the stepped attenuator physically moves a notch.

Conclusion The Genoa Preamp is the second offering from Sonus Veritas that's come my way. It bears much the same signature as their Venice Phono Preamp I reviewed last year. Indeed, excepting the RIAA circuitry, a lot of the design choices and internal parts are identical. Like the Venice, the Genoa does about average on the audio scorecard for products at this price point. I can't say it is better than some other pricey preamps of my acquaintance. Yet, given quality source, it was capable of producing some of the best sound ever at Nack Labs. The Genoa, like the Venice, is extraordinary at reproducing texture, musical contrasts and tonal color. This had a beguiling effect on most listeners and made listening a real pleasure. Highly recommended for audition by classical and jazz enthusiasts, especially those who place these commodities at the top of their list. Marshall Nack

Genoa Preamp

Optional System Remote

Sonus Veritas

|