|

|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 59

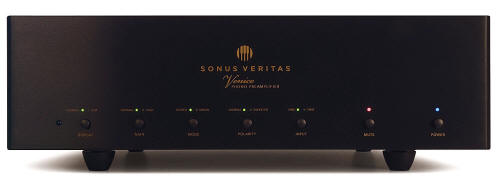

sonus veritas Venice Phono Preamp as reviewed by Marshall Nack

For the first week after receiving the new Venice Phono Stage from Sonus Veritas, I could not put pen to paper. First impressions are immediate, gut reactions—they often become main points in the review. The trouble I was having now was that my impressions were inconsistent. The Venice made some of my reference LPs sound glorious, indicating I had in a contender. But no sooner did I arrive at that, I would put on another only to find it less involving.

Take Debussy's "Nocturnes" from Monteux Conducts the London Symphony Orchestra as an example (London CS 6248, Blueback label). An old reference, it now sounded weak, thin and distractingly noisy. My mind raced: Was something wrong with the cartridge? But then I put on Monteux conducting the same work with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (Victrola Plum label, VICS-1027). Now my jaw was left agape, to use a classic high-end expression. (This is a great, unheralded, golden age RCA recording. Just don't bother with side one.) I kept receiving these conflicting impressions. Which way was up? Designed to be Honest It took a week of nightly sessions to get my bearings. Finally, an Ah, Ha! moment when I played a Classic Records reissue of Spain, with Reiner conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (single-sided, 45RPM, heavy weight pressing of LSC-2230).

Yes, the first movement began by sounding a little compressed and congested—duly noted. But the second movement, track two of the same side, came pummeling out, exploding with room-filling crescendos. Ah, ha! The light bulb clicked on. This made sense from a musical point of view. The conductor is holding back in the first movement in order for the crescendo in the second to be all the more impressive. This is clever and effective technique on Mr. Reiner's part.

The compression of the first movement was in the source. The Venice was only acting as the messenger, serving up penetrating insight into the groove modulations and doing it with greater honesty than I'm accustomed to. At the time, I was using the Dr. Feickert Blackbird turntable, another component known for its prowess at deep groove diving.

And so it went. The better the LP, the more illuminating insight I was granted and the more the Venice out-distanced competing phono stages. But I had to be careful to spin only my best discs, those in near mint or better condition. Any dirt, any pressing defect—you're gonna hear it clearly and undisguised. Equally remarkable, the Venice was capable of this resolution yet wholly escaped the trappings of analytic sound. Violins and woodwinds displayed great timbral fidelity and beauty of tone. There was plenty of bloom and body, while quiet passages had delicate inner details. Brass Transients Let's cue up Janácek's Sinfonietta with Claudio Abbado and the London Symphony Orchestra (Speakers Corner reissue of Decca SXL 6398). I often think of this very popular composition as Eastern Europe's equivalent to Aaron Copland's Fanfare for the Common Man, a brass chorale trotted out for so many official occasions it has become akin to a second national anthem here in the USA.

Much ink has been spilled about the difficulty of getting the initial blat of brass instruments right. What is needed is a jagged, edgy attack, relatively thin in body, full of odd order harmonics, but not too aggressive. Then, as the note moves into the sustain phase, it morphs and becomes more full-bodied and even-toned. It thins again and loses body going into the tail as it fades away. What we're talking about is mutations in timbre, body shape (zaftig or lean), texture and micro-dynamics as they change over the life cycle of the note. This is not what we typically define as resolution, per sé, although it involves changes in the source. In the past, I have heard this chameleon-like sonic behavior using phono stages employing step-up transformers. In fact, according to some aficionados, including Mr. Carter, this is the only way it can be reproduced. The hybrid Venice, which employs coupling transformers both on input (step-up) and output (step-down), captures that blat—and the other mutations—and expertly nails it. The vividness of the Venice makes a really good solid-state design, like my reference ASR Basis Exclusive, seem like a black and white TV set in this regard. Step-ups are incorporated in some tube designs, but I've yet to see one in a solid-state unit. There's no chance you'll hear these continuously shifting dynamic and harmonic relationships over time without one in the loop. Solid-state phono stages tend to finish the note much like they start it, with no changes in image shape, let alone altering of timbral color. The whole dang thing has a consistent quality over the entire life cycle of the note. Indulge me in an interesting sidebar here. Some people think a case can be made that what I'm describing is also the major issue facing digital playback, ratcheted up another degree. Here's the theory. All playback is event-driven. With digital, as with solid-state phono stages, what I hear is that an event once begun stays the same until it fades away at the tail. It is as if signal changes must be greater than a certain threshold value for the circuit to register them. The threshold is apparently set too high, because very low-level changes that occur once an event has started get lost. Hence, playback acquires a blunt, abrupt quality. Notes may have duration over time, but lack continuousness—that curvy, wave-like motion integral to acoustic sound. Notice, I'm making a distinction here. Digital is capable of surpassing resolution of discrete events. The problem lies with small changes after an event has begun.

Dynamics Let's shift to dynamics. In general, expectations are not high for a tube-hybrid, step-up design. But time and again, the Venice's macro performance took me to expected SPL levels… and then continued building, leaving me to assume that classic jaw agape profile. The Venice caught me off guard by its headroom. It's the kind of exotic macro performance rarely encountered; when it is, the price tag is always steep. The Venice scales to full orchestra with no problem. As the music grows, the soundstage swells, helped along with slightly oversize images. And the peaks it scales are clean and distortion free. Furthermore, because the tonal balance tends to favor the lower mids and bass, the unit has plenty of slam. Bass goes low and with authority.

Getting back to Janácek's Sinfonietta, the brass are arrayed along the rear wall, trumpets are split left and right, in front of the centered trombones and tuba. The timpani emanate from behind the brass, the double basses are to their right. Well into the piece there's even a bell: when struck, it resonates forever. The stage begins just behind the speakers and the receding layering is clear as day. The instruments are arrayed seamlessly across the width of the room. I could easily draw the players seating arrangement on a piece of paper. As for the transient itself, speed is good, while integration and coherency are superb; so good that it never occurred to me to examine them. A Winning Formula I want four things in a component: accurate timbre with low coloration; musical flow; powerful dynamics; and decent resolution. Combine these and you have one of the most potent formulas in audio. The Venice has them all. The Venice does not conform to type. (Type being defined as a tube-hybrid, step-up phono preamp.) Or does it? With the Vinyl Reference and a Venice prototype I was sent earlier, transients were a little soft and bass a bit warm. The picture consistently veered to the pretty side. Certainly, if you put the Venice along side a first-rate, solid-state design, there is no getting around the fact that it sounds like tubes. However, and this is a major difference from Kevin's previous attempts that I've tried, it is not overdone. The production Venice hews much closer to center on the neutrality dial. That's why I'm hearing these differences from LP to LP. Most recently I was listening to the Ypsilon VPS-100 and the Veloce LP-1, two phono stages employing step-ups. Neither suffers the limitations of the stereotype. So, let's put these pernicious notions to rest, once and for all. The current generation of step-up designs has beauty of tone without the lingering compromises associated with them in the past. Putting it in Perspective I've demo-ed many phono stages in the $10K and lower price range. There is no question the Venice out-distances these by a healthy margin. At $20K, there may be others that sound great; I don't know, not having much experience at this price point. That leaves me to talk about higher priced units, like the Ypsilon VPS-100, at $29K (price including a mandatory outboard step-up transformer) and the Soulution 720 line stage preamp with built-in phono, at $45,000. For refinement and sheer credibility, nothing beats the VPS-100. On the other hand, the Venice brings more brawn to bear. Plus, it has that honesty. With the VPS-100, less than perfect LPs still sounded great. In addition, the Venice is more user friendly and flexible to use.

As for the built-in phono in the Soulution 720 preamp, nothing I've encountered offers its penetrating level of resolution, which is like upgrading to HDTV. But you won't get the musical flow of the Venice. Some Background A word or two about the company and the designer. Sonus Veritas was founded in 2009 by two audio enthusiasts, Joe Rosovitz (President) and Kevin Carter (VP and Chief Engineering Officer) to produce a suite of products targeting the upper end of the market. My initial contact with the company came about while I was reviewing the old Vinyl Reference Phono Preamp, marketed by Art Audio. This mid-price phono stage (MSRP $5000, alas NLA) was enthusiastically received by consumers and reviewers alike, including yours truly and, in due course, landed on Stereophile's Recommended Components listing. In the course of that review, Joe Fratus of Art Audio put me in touch with Kevin for the technical interview. We hit it off and have kept up a casual communication ever since. In the meantime, Kevin's been busy with his new phono preamp. This time around he was unshackled from price and design constraints and now we have the Venice Phono Preamplifier, the inaugural product of his new company, Sonus Veritas. Other products debuting now include a line preamp and a DAC. Cosmetics and Features The rather large aircraft-grade aluminum chassis weighs 50 lbs. It is conventional in appearance and will not call attention to itself on your rack, the kind of matte black box that you might find from many small manufacturers. Close inspection reveals superior fit-n-finish. It is evident that much care and thought went into the chassis manufacture.

It has two inputs that are switchable from the front panel. Each has independent gain and loading controls and even its own ground post. (This is a very useful feature if you're running two turntables or tonearms.) Remote Control The Venice comes with a system remote shared with their line stage and DAC. All of the front panel functions are accessible from the remote. In operation, the units' top plate gets too hot to touch. The manual recommends a minimum of 1-inch clearance on top. I would make that 3-4 inches clearance, if you can spare it. One caveat: the Venice does not remember the last setting for Gain (Lo – Hi) or Polarity (Normal – Inverted). After shutdown, it reverts to Lo and Normal, the defaults, when you power up. Circuit Design The Venice is a differential hybrid design. In its MC cartridge setting, the signal first sees a rather special step-up transformer. This particular Lundahl transformer features a cobalt amorphous core and coils wound with Cardas copper wire. It is new and purpose built to Kevin's spec. Next, the signal encounters FET transistors, and finally triode tubes, comprising a classic Cascode input circuit design with FETs on the bottom followed by tubes on top. Coupling capacitors are not used anywhere in the signal path. There are three gain stages. RIAA equalization is accomplished with two separate networks configured passively between the first and second, and second and third stages. The first and second stages are direct coupled to maximize sonic purity; the second and third stages are transformer coupled, with an iron amorphous core transformer, the same type as the output transformer. The Venice has plenty of gain and can handle virtually any cartridge, from an MM to an MC with .1mv output. Loading is adjustable from 25 through 47K. I loaded my Shelter Harmony at 150 ohms. There are two Russian type 6N23P (or 6N23P-EV) tubes on the input amplification stage. These are NOS, usually from the 1970s, and imported directly by Sonus Veritas. There are four current production 6N30P (or 6H30Pi) in the second and third stages. Each stage on input and output is internally differential. Therefore, a balanced input phono cable and balanced interconnect wires are optimum. You connect your RCA terminated phono cable to one set of inputs. If it is balanced, set the input toggle to XLR. (An RCA terminated phono cable can be internally constructed to either SE or balanced.)

All cabling—phono cable, balanced and single-ended ICs (I tried both) and power cord—were from Kubala-Sosna. Best sound was with the front panel Gain set to Low. For most of the review period I was using my mbl 6010D preamp and a pair of mbl 9008A monoblocks. At normal volume settings and with the tonearm lifted, there was no audible sound from the listening seat. The Venice is nearly as quiet as the ASR. Conclusion Back when I reviewed the Vinyl Reference Phono Preamp, I said, "It would be my top choice for fare employing small-scale forces… where intimacy is desired… But the tables would be turned if I wanted to listen to a symphonic work by Mahler." In that eventuality, I would turn to the ASR Basis Exclusive, the pacesetter in the group of phono stages under review four years ago. Now along comes the Venice Phono Preamp, the inaugural offering from Sonus Veritas, a new company with the man responsible for the Vinyl Reference in the designer's seat. The Vinyl Reference and the Venice have much in common, both in sound and design, and you can make a case that the Venice completes what the VR started. But this time around there are no compromises in parts or vision. And this time I have no caveats. The Venice does just about everything right, from timbre and tone to dynamics and resolution. I look forward to playing Mahler symphonies with it. Plus, it is chock full of user-friendly features and has a remote. The only (weak) rub I can come up with is the Venice's honesty mandates careful choice of source material. Any dirt, any pressing defect—you're gonna hear it. Putting price in perspective, the Venice is expensive at $20K. At this price point, there may be competitive units—I don't know, I haven't auditioned any others. However, if you want truly SOTA playback you will spend even more $$$. And I can tell you, based on a lot of experience at $10K and under, you won't find anything approaching the Venice's level of performance there. Strongly recommended for audition. I'm considering acquisition for the reference system. Marshall Nack

Venice Phono Preamp

Sonus Veritas

|