Every so often, a music release occurs that is of such historical and musical significance that time must be made to mark its arrival. So it is with this amazing restoration of the BBC's 2-microphone live recording of Jascha Horenstein's Mahler Symphony No. 8 "Symphony of a Thousand," recorded live in 1959 in Royal Albert Hall, London. If you are a classical music lover, this music and this performance must be part of your listening experience.

Mahler Symphony No. 8 (Symphony of a Thousand), Busoni Orchestral Works, Jascha Horenstein, London Symphony Orchestra. HDTT 1959 2025 (DSD256, DXD, Stereo) HERE

Jascha Horenstein's recording of Mahler's Symphony No. 8 ("Symphony of a Thousand") has long been considered "definitive." For many, this performance is the gold standard by which to compare all others. Some may equal it, but few if any have superseded it. Horenstein and his massive forces (756 performers) achieve a remarkable creation reflecting a near perfect balance of delicate, heavenly beauty with moments of overwhelming power. There are layer and layers of dynamics in this performance, all carefully judged, all flowing beautifully throughout the arch of this hugely complex work, and never losing the thread. The depth of feeling is simply astounding—enough to carry one away completely.

The Music

Mahler's Eighth Symphony is a monumental work for large orchestra and chorus, exploring themes of love, redemption, and the human spirit. It is divided into two parts. The first part is a powerful setting of the Latin hymn Veni, Creator Spiritus invoking the Holy Spirit and celebrating creation and divine grace. The second part is based on the final scene of Goethe's Faust, delivering an extended celebration of Faust's ultimate redemption as he is received into heaven, thwarting Mephistopheles' efforts to capture his soul. It depicts the redemption of Faust through love and the Eternal Feminine and provides an expansive vision of heaven portrayed in the most tender and lovely music imaginable, eventually culminating in a mighty conclusion by the massed forces. Mahler masterfully unifies the disparate texts of the hymn and the Faust scene through shared musical themes and a common exploration of love and redemption.

Importantly, unlike many of Mahler's other symphonies, the Eighth is is imbued with a sense of optimism and spiritual transcendence, particularly in its depiction of love and redemption.

The power of the conclusion to the symphony is staggering—keep you hand near your volume control because HDTT has not compressed the dynamics. And given the microphone placement somewhat back in the hall, you may need a bit more volume than your normal setting for the earlier, quieter parts.

The included Busoni Orchestral Works are sourced from an entirely independent recording made by Jascha Horenstein and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. These three orchestral pieces by Mahler's contemporary, friend and colleague, Ferruccio Busoni, are historical studio performances made for later broadcast. HDTT says they are commercially released here for the first time. The pieces are most enjoyable, nicely performed, and reflect an important connection between the two composers.

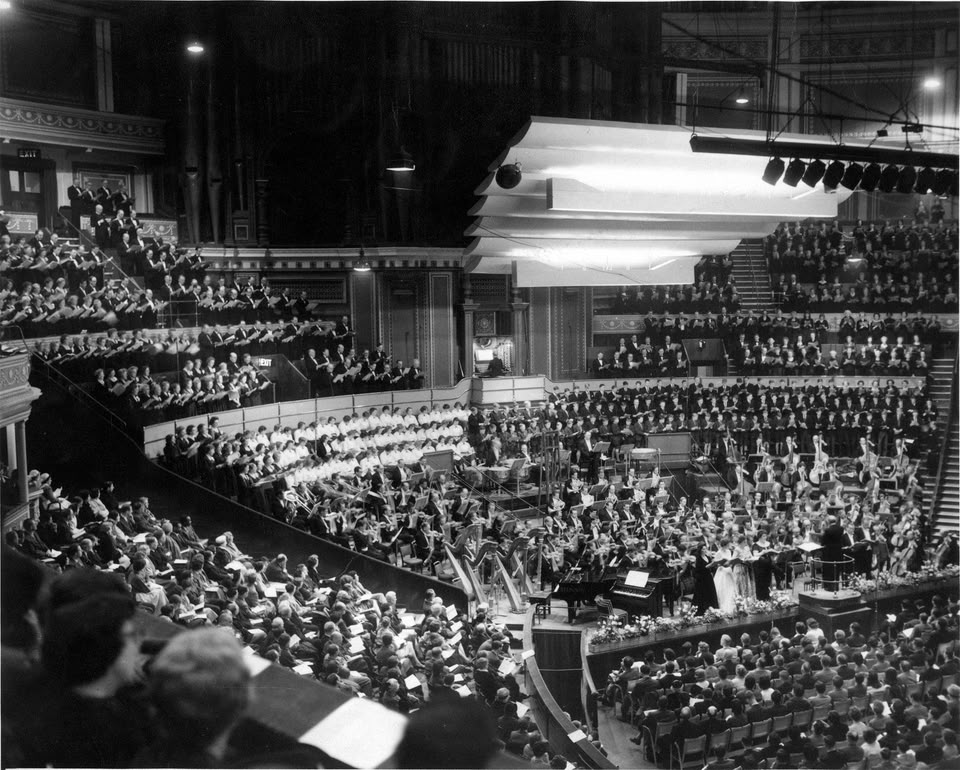

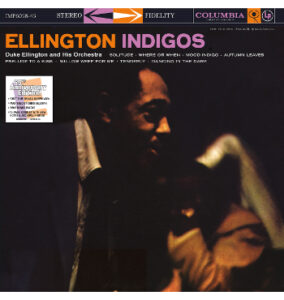

What it took to create this performance

The Eighth Symphony is rarely performed simply due to the logistics and cost of assembling such a large array of performers. To fully understand what we are hearing, one must first view the photo of the occasion (see cover). Royal Albert Hall is in a large elliptical, domed building, and in the interior photo we can see the large orchestra seated "down center," with tightly packed choristers seated both behind it and stretching upward toward the top of the hall on either side, far above the orchestra. As seen in the photo, the orchestra and soloists are literally engulfed by the sea of choristers that surround them. In this 1959 event, the huge hall was said to be occupied by an audience of almost 6000.

In this performance we have a much augmented London Symphony Orchestra (144 players, with ranks of additional trumpets and trombones in the upper right balconies), the massive Royal Albert Hall Organ, five choruses/choirs comprising 600 singers, and eight vocal soloists. Among the performers are names well known to many: Helen Watts as second alto, Neville Marriner in the first chair second violin, trombonist Denis Wick (familiar as the great trombone soloist in the 1970 Horenstein/LSO recording of Mahler Symphony No. 3) as first chair among seven; James Galway is one of four piccolo players; Gervase de Peyer is first clarinetist; and Barry Tuckwell is first hornist, among nine.

That this performance ever occurred is something of a modern miracle. Plans to put his on started percolating in October 1958 with the approaching Mahler centenary just over a year away. The BBC undertook to organize the performance that they would broadcast. EMI was approached by Horenstein's agent about making a commercial recording of the performance, but EMI's Manager of International Artists, David Bicknell, turned down the project responding, "We don't want this work at the present time." So, the BBC forged ahead to record both a mono release for broadcast and a stereo tape recording with independent microphones.

Assembling orchestra, chorus, and soloists for a performance to be held barely five months away was a huge challenge. Misha Horenstein, the maestro's cousin and a champion of his works, has written an excellent essay about the challenges which I encourage you to read, HERE. The choice of vocal soloists was a challenge. Approaches to six well-known artists were declined either due to not being available or not willing to take on the project at such short notice. But, all turned out to be fortuitous because the ultimate selection of vocalist resulted it distinguished performances from every one of them. As of the beginning of February, the selection of soloists and finalization of choruses was yet not done, and Horenstein was understandably agitated.

Finally on February 11 choir rehearsals started in earnest. Horenstein arrived the week prior to the schedule performance to begin working with the orchestra—none of who had ever played this music and, for the most part, were not familiar with the music of Mahler at all. Horenstein taught them the music as they rehearsed.

Misha Horenstein writes, "The only full rehearsal with everyone present took place on the evening before the concert at the nearby Royal Academy of Music, whose platform was not large enough to comfortably accommodate everyone, forcing Horenstein to conduct from the right side of the stage with the huge orchestra arranged in some manner in front of him and the choruses occupying the seats in the auditorium to his left. However, these arrangements and the constant changes of venue did not appear to disturb him: 'The rehearsals are going very well;' he wrote enthusiastically to Alma Mahler, 'all are in great excitement and I am occupied day and night with the score, therefore unspeakably happy.' "

The dress rehearsal took place on the morning of the concert, but without the amateur choirs. At no time before the performance was there a full rehearsal in the auditorium with all the participants present.

All of this is remarkable to consider when listening to this flawlessly executed performance. The superb results are a testament to the excellence of Jascha Horenstein's leadership, teaching, and conducting skills. And the performance is a great testament to his musical sensibilities.

The Sound Quality

With John Haley's immensely successful restoration, it is now possible to hear, in tremendous clarity and detail, all the parts that are intersecting, layering, and intertwining. That this degree of clarity can be achieved from a 1959 recording made with only two microphones (set in a coincident configuration) is remarkable. The outcome is a testament both to the BBC recording engineers who determined the optimal position of these microphones and to John Haley for his efforts to tease out the detail and reduce the inherent noise in both the source tape and the audience. John comments in his blog post about this restoration:

"The fact that this early experimental stereo recording relied on coincident, or nearly so, stereo mic placement turns out to be a virtue, avoiding a nightmare of phase incoherence that might have resulted if multi-miking had been attempted. Despite the distant mic placement, a generous amount of musical detail was captured, including clear audibility and definition of orchestral as well as vocal solos, all of which is enhanced by the new-found clarity of the excellent tape source and the high-resolution dubbing of it.

"A disadvantage is that the mic placement also captured with great clarity a vast amount of audience noise, including every kind of respiratory noise known to man. We have managed to remove or at least ameliorate a great deal of that audience noise.

"Other issues involved repairing tape dropouts and correcting the meandering pitch of the original to present the whole recording exactly on pitch, something we believe (without conducting an extensive survey) is probably a first for this recording. Fortunately, a large dynamic range was well captured, which of course we have not compressed; this means that the regular volume level may seem on the low side, so please turn it up, but with an awareness of what is coming at the huge climaxes."

See HERE for John Haley's complete post about this restoration.

This recording has floated around in the gray areas of bootleg releases ever since it's recording in 1959. There have been some LP releases, but their sound quality is nowhere near the quality of this new release. HDTT was able to obtain an excellent stereo source tape, with John spending countless hours massaging the high resolution digital transfer of that tape into something that finally represents this great performance in the sound quality it deserves.

Concluding Thoughts

No, this does not sound like a modern recording. And, the sound is very much from "back in the hall." But, once one adapts to that, excellence of the sound quality begins to shine forth. The clarity and detail are remarkable. The brilliance of the brass superb, the clarity of the massed choruses (that amazing British training of choral groups truly shining here) is astonishing, and the soundstage balance is eminently pleasing.

Most importantly, the superlative quality of the performance and the music simply pulls one into the experience, forgetting utterly about the various sonic nits. The overpowering emotional response evoked by this performance simply swamps lesser considerations. When the final movement ended, I was ready to leap to my feet in applause along with the 6,000 attendees in that hall that night.

Just a marvelous performance, an excellent performance, and a remarkable restoration. Well done, HDTT. Well done Bob Witrak and John Haley. And thank you.