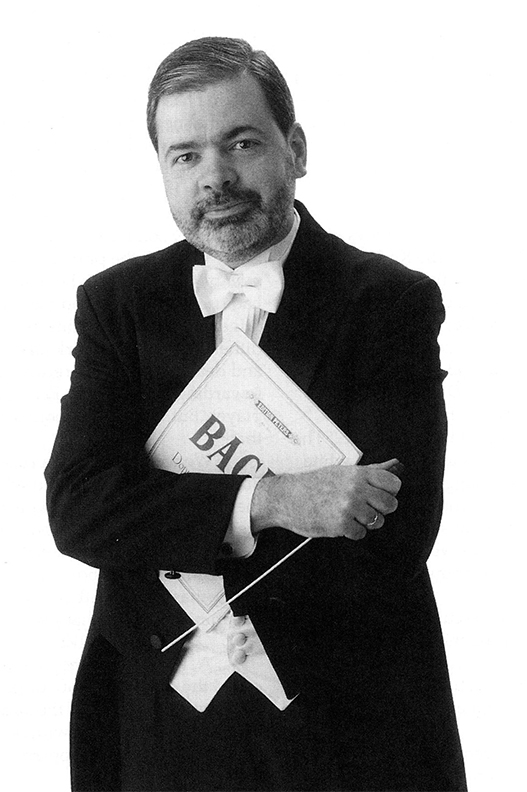

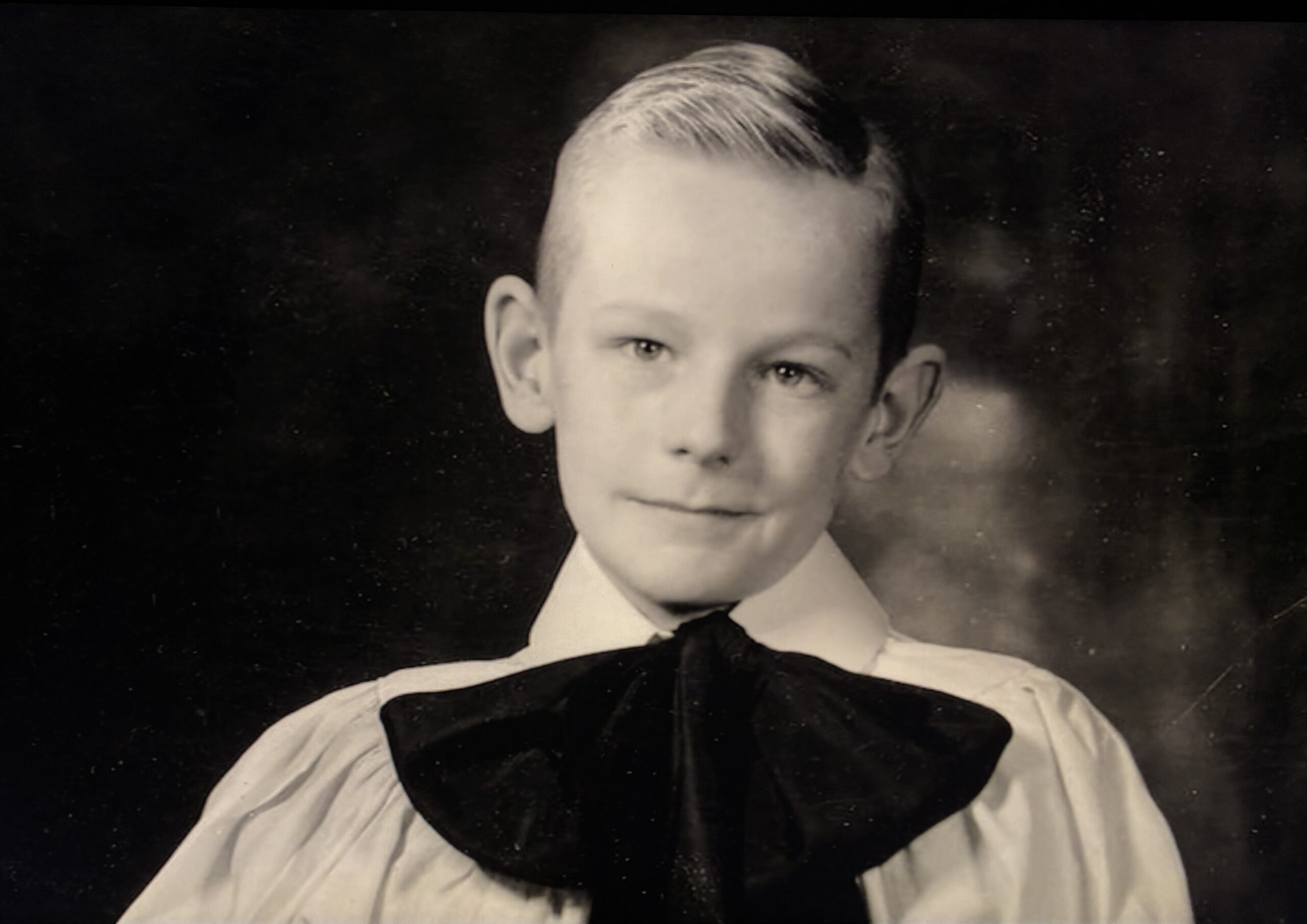

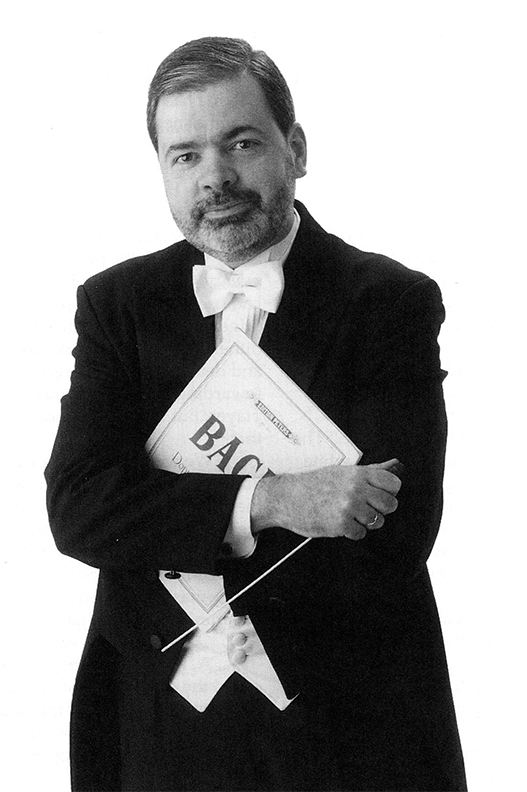

John Marks is a multidisciplinary generalist and a lifelong audio hobbyist. He was educated at Brown University and Vanderbilt Law School. He has worked as a music educator, recording engineer, classical-music record producer and label executive, and as a music and audio-equipment journalist. He was a columnist for The Absolute Sound, and also for Stereophile magazine. His consulting clients have included Grace Design, the University of the South (Sewanee, TN), Steinway & Sons, and the Estate of Jascha Heifetz.

The Swan of Barney's Pond, Lincoln, Rhode Island. Photo by John Marks.

Qobuz Part 2 Playlist:

https://play.qobuz.com/playlist/27618531

Here are my "Delightful Discovery Dark Horse" orchestral-programming picks, numbers seven through twelve:

Claude Debussy, La mer (1905)

Dark Horse: Jean Sibelius, The Swan of Tuonela (1895)

The college Music-History Survey textbooks all seem to credit Igor Stravinsky's 1913 Rite of Spring as the genre-defining piece of "Modern" classical music. That well might be the case.

However, my problem is, I think that Rite of Spring truly, totally sucks—as music, period. I'd never voluntarily go out of my way to hear it live.

I think that a ballet wherein the prima ballerina dances herself to death is not art; it is anti-art. Yes, Rite of Spring is powerful; but it was manufactured in a very dark, primeval (and, obviously, pre-Christian) corner of the Russian soul.

I find Hubert Laws's rather heroic small-jazz-ensemble version of Rite of Spring tolerable to listen to. But that is my least-favorite track on Laws's otherwise very wonderful 1971 LP of that same title. Qobuz link here.

There might not have been a "riot" the night of the first performance of Debussy's La mer. But I honestly think that La mer ("The Sea") has been a more important factor in the ongoing development of music than Rite of Spring has been.

Here, I speak of classical music. But I also have read claims that John Williams put a few subtle La mer references in his score for the film Jaws.

To reduce things perhaps a bit too far, the main difference between the two works is that Rite makes a lot of noise and pretty much yells at you. But La mer presents you with a succession of beautifully-shaped musical phrases; phrases (and harmonies) that very well might strike you as things you have never heard before.

Note, I do not mean to suggest that Rite of Spring is played all that much today. I don't think it really is. I also think that that is one more indicator of Rite's essential cosmic suckitude. I am merely contending that Rite's alleged continuing importance is just some kind of an academic security blanket. Or, a talisman that identifies you as one of the Elect.

Listening to La mer, you are not going to be reminded of Beethoven or Schubert; and you are not going to be reminded of Wagner, either. Perhaps that is why orchestras do program La mer a lot.

Examples: The New York Philharmonic has played La mer a total of 141 performances since 1917. Whereas the Boston Symphony Orchestra's tally is 332 performances since 1907. I think that's a lot. But the Boston Symphony Orchestra's roots (arguably) are every bit as French as they are German.

As a "delightful discovery" alternative, I suggest Finnish composer Jean Sibelius's similarly-watery tone poem The Swan of Tuonela. (BSO tally: 65 performances.)

"The Swan of Tuonela" is a figure in Finnish mythology. I don't know if Finnish mythology assigns a gender to the Swan. But I do think of the Swan of Tuonela as female – a female swan placidly floating on the streams and ponds of the pagan Finnish vision of the Afterlife. You know, she's one of those females who is as indifferent to your death, as she had been indifferent to your life.

Perhaps I am being unfair. But nobody can claim that The Swan of Tuonela isn't unruffled. Unruffled she is, by your picky little problems (such as death). (That's a Pagan Thing.)

Well, if that doesn't tempt you into listening, I can't imagine anything that will!

Samuel Barber, Adagio for Strings, Op. 11 (1938)

Dark Horse: Delius, "The Walk to the Paradise Garden" (1907)

Nobody would ever mistake Samuel Barber's "Adagio for Strings" as a movement from Rite of Spring, and that is all to the good. My educated guess is, the chief reason for Barber's Adagio's popularity is its near-total lack of "Look at Me," self-conscious 20th-century musical-Modernism posturing.

Barber chose his simple (musical) building blocks with care; and then he put them together with subtle craftsmanship. Let me try to illustrate what I mean, by an analogy.

There was a 19th-century aesthetic movement in Britain called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (really!). "Pre-Raphaelite," in that they purported to reject all the "innovations" in the art of painting from the time of Raphael, on. (Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, 1483-1520.)

The target of the Pre-Raphaelites' scorn was Renaissance art's default (or mechanistic) use of Classical settings and poses, which were placed within overall compositions that might have been elegant, but only for the sake of elegance.

At least in the minds of the Pre-Raphaelites, the Raphaelites failed the test of creating an honest reflection of reality. If we can imagine Samuel Barber as a Pre-Raphaelite (but a Pre-Raphaelite composer of music, rather than a painter of paintings), I think the analogy clicks into place.

In his Adagio for Strings, Barber melds simplicity with complexity.

Yes, Barber's main melody proceeds simply and stair-stepwise, in "arch" formations. Yes, Barber's simple, rough-hewn harmonies recall the music of the transitional period between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Music such as the "Agincourt Hymn," from the early 1400s. (Look for it on Qobuz, either as an organ piece, or a choral reconstruction.)

However, on the other side of the ledger, there is a wealth of subtle complexity. Barber starts with a 4/2 time signature. I have no idea what was in his mind when he varied that meter by measures in 5/2, 6/2, and 3/2. But one explanation that works for me is that, when a person is sobbing, sooner or later they will have to catch their breath. There's also that famous long pause. We all hold our breaths, waiting and hoping for closure.

Barber also divides his orchestral strings not just in the usual five sections (first and second violins, violas, celli, and double basses). At times, he subdivides all the sections except the double basses. That lends an air of otherworldly, nebulous numinosity to the quiet passages.

But that complexity folds in upon itself when the time comes for the plainspoken chordal climaxes, which are based upon the primal musical interval of the third. And, to quote Blues Traveler, those chordal climaxes are the "Hook" that brings you back.

No surprise, Adagio for Strings was nationally broadcast in 1945, after the announcement of President Roosevelt's death. Also, it was played by the National Symphony Orchestra in a nationwide broadcast following the funeral of assassinated President John Kennedy. Supposedly, Barber's Adagio was one of Kennedy's favorite pieces of classical music. And on and on.

So, in my view, Barber's Adagio for Strings certainly deserves its fame.

But can't we listen to something else for a few minutes? Please? Pretty Please?

To the rescue comes the obscure, neglected, tragic German/English composer Fritz (later Frederick) Delius (1862-1934). Delius was born in England, but to a German family with Dutch roots. His family was mercantile and successful. So, they assumed that young Fritz would jump at the chance to join the family business. Which he chose not to do.

In an effort to "split the difference," his family arranged to have him manage an orange plantation in Florida. Fritz Delius thereupon went to Florida, and ignored his business duties. But he was strongly influenced by the African-American music he heard in Florida. Lots of back-and-forth eventuated, but Delius eventually picked up some sort of a formal music education, as well as a wife with an income more steady and secure than his.

Delius and his wife Jelka (née Rosen, an artist) collaborated on an English-language opera (A Village Romeo and Juliet) based on the short story "Romeo und Julia auf dem Dorfe" by the Swiss author Gottfried Keller. (In toto, Delius wrote six operas.)

Yes, we both see the looming tragedy. The opera is famously unwieldy to stage, but the orchestral interlude between Scenes 5 and 6, "The Walk to the Paradise Garden" (a pub), is heard separately in concerts, and has been recorded many times. Pretty much all the positive things I said about Barber's Adagio also apply to Delius's "The Walk to the Paradise Garden." You must hear it!

Johannes Brahms, Ein deutsches Requiem, Op. 45 (1868)

Dark Horse: Morten Lauridsen, Lux Aeterna (1997)

Johannes Brahms had a difficult upbringing. His father was a somewhat unsuccessful musician. When young Johannes showed signs of real talent on the piano, his father promptly lent him out to Hamburg's dockside bars and brothels, where he would play the piano, to lend a little "class" to the goings-on.

The working girls would (I assume mockingly) "come on to" young Hansi (or whatever nickname they had for him). That caused the teenage Brahms much embarrassment and anxiety.

Brahms never married. Supposedly (and I have discussed this issue viva voce with Brahms's most prestigious living biographer), Brahms had internalized the "Madonna/Whore" emotional dichotomy to the extent that, in adult life, he could only have sexual relations with "Angels of the Night."

The things that parents do. (Note, you could overfill a landfill with all the academic back-and-forth over the issue, "The Young Brahms and The Prostitutes: 'Yes' or 'No'?")

There's a perhaps-urban legend that once, upon leaving a house party, having opened the front door to leave, Brahms turned back around and loudly declared, "If there is anyone I have failed to offend, I promise to make it up next time!"

But most troubling for me is that Brahms was an ardent supporter of Prussian militarism as the way forward for a united Germany. When the Prussians kicked the French where it hurt in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) Brahms dutifully wrote his Song of Triumph for vocal soloist, orchestra, and chorus.

Which was unfortunate. At least from our perspective, of more than 150 years later.

That's because it is way too easy to "connect the dots" wrongly, between Brahms's Triumphlied and his German Requiem. That is, it seems natural to assume that the so-called German Requiem (of 1868; and therefore, it was composed before the Triumphlied) was just one more example of Brahms's German-Supremacy Mongering.

That actually is not the case. At all.

Brahms could have saved all of us a lot of trouble, if he just had had the frammis to title his symphonic meditation upon death his Human Requiem, rather than his German Requiem.

Why would that have made sense? A few reasons. The point that Brahms was trying to make was not that German culture was inherently superior. He wanted people to know that, instead of the usual Latin-language Mass texts, he was, first of all, setting German texts. Secondly, he wanted people to know that he was not setting a Requiem Mass; his work would be non-Liturgical.

By way of a sidebar digression: If you are ever called upon to state the parts of a Latin Mass that are usually set to music, the memory device you will really want to know is the sentence:

"Kenny G. Caught Scrofula, and Died."

For:

Kyrie

Gloria

Credo

Sanctus

Agnus Dei

Finally, and I think that this is generally under-appreciated today, Brahms carefully chose from Martin Luther's Bible texts, studiously avoiding any reference to Jesus, or to the salvific nature of Jesus's suffering. Indeed, Brahms's lack of reference to specifically Christian dogma is total. Therefore, the German Requiem might have been an early attempt at "Inclusivity." How about that?

The German Requiem does not consist of intercessory prayers that the souls of the dead might linger in Purgatory for shorter intervals of time. Brahms wrote his work for the living, not for the dead. The first sentence the chorus sings is:

Blessed are they that mourn,

for they shall be comforted.

I think it relevant that Brahms's mother died in 1865, causing him much grief. And it was in 1865 that Brahms began writing the German Requiem. Another factor might have been Brahms's lasting sadness over the tragic, messy decline and death of his beloved mentor Robert Schumann.

I am sure that all of the above strongly contribute to Brahms's Ein deutsches Requiem's "Evergreen" status. But, all is not beer and skittles. EDR is Brahms's lengthiest work. It doth go on. And on. For more than an hour.

Secondly, EDR is not one of those orchestral works that "play themselves." The massive double fugue (with tympany hammering away non-stop), requires a very deft touch, if it is not to come off as cold mashed potatoes with a side dish of lumpy gravy. So, a "Certified War Horse," EDR is.

By the way, whenever Brahms wanted to pull in a few quick Deutschmarks by churning out lightweight salon pieces for home enjoyment, he used the nom-de-plume "G.W. Marks." Perhaps Brahms thought "Marks" was as Generic a German family name as you could pick. I of course have no opinion on this.

Now, back to the "Dark Horses" versus the (Orchestral) "War Horses."

Fortunately, there is a 20th-century Latin-language Requiem that was patterned on Brahms's German-language work. I think it packs as hard an emotional punch—and perhaps even harder.

That work being Morten Lauridsen's Lux Aeterna, for chorus and orchestra (the middle movement is a-cappella). Lux Aeterna is one of the most-often performed works for chorus and orchestra written in the 20th century. The name "Eternal Light" refers to the fact that all the Scripture texts that Lauridsen chose to set mention "light."

I suspect that, over and above Lux Aeterna's essential transcendent beauty and emotional authenticity, there might be a practical consideration that is also involved in its remarkable popularity. Lux Aeterna is for chorus and orchestra. But, unlike Brahms's Ein deutsches Requiem, there are no vocal soloists. An all-volunteer community chorus, all other things being equal, will find it easier – from a financial standpoint – to present Lux Aeterna than Ein deutsches Requiem. That's because they won't have to pay professional vocal soloists.

Morten Lauridsen is Distinguished Professor of Composition (Emeritus) at the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music. In 2007 he was awarded the United States National Medal of Arts "for his composition of radiant choral works combining musical beauty, power, and spiritual depth that have thrilled audiences worldwide." (Another 2007 honoree was electric-guitar pioneer Les Paul.)

Hearing the first notes of Lux Aeterna on a good stereo system with adequate bass extension justifies the outlay for a superb stereo. The first chord is on D, and it is six octaves tall. (Orchestral string basses are notated an octave above their actual pitch.) The bass line, at the same time pithy and motoric, is something Brahms would have been proud to have written. The shade of Brahms hovers over this 1997 work, although Morten Lauridsen is entirely his own composer.

Lux Aeterna gives off a vibrant glow, despite its being a setting of five choral texts usually associated with the Latin Mass for the Dead. And of course, Lauridsen's shaping of his choral melodies looks back over its shoulder to Gregorian Chant.

The overall architecture of the piece—strongly symmetrical—finds parallels in Brahms' Ein deutsches Requiem, although I also hear echoes of Janácek's distinctive tonality. Critic David Patrick Stearns is probably closest when he mentions Aaron Copland's forthrightness of expression as a probable influence on Lauridsen. But neither Charles Ives nor Roy Harris could be faulted if they were to feel a little pride too.

You have to hear it to believe it, but Lauridsen managed to write a Latin-language Requiem, in an unmistakably American idiom. What is even better: It works. The last reprise, on the word "Sempiternam" (Forever) never fails to bring tears to my eyes.

Lux Aeterna is at once haunting and consoling, and a composer probably can't ask for more than that. Serious music indeed for serious times indeed, but Lux Aeterna is also resolutely confident, and confidently joyful.

Ralph Vaughan Williams, Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis (1910)

Dark Horse: Ralph Vaughan Williams, An Oxford Elegy (1949)

For lack of a better analogy, Ralph Vaughan Williams's Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis is the U.K.'s answer to Samuel Barber's Adagio for Strings. (Yes, of course I realize that Vaughan Williams published first.)

Pedantry Note 1: Vaughan Williams's compound surname is of Welsh origin. It means "Williams the Younger" or "Williams the Smaller." By the way, his first name is pronounced "Rafe," not Ralph. I gather that that also is a Welsh thing.

Barber's music is all original; but Vaughan Williams borrows the thematic material he writes variations upon from Thomas Tallis's 1567 setting of Psalm 2, "Why do the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing?"

Pedantry Note 2: I quoted Psalm 2's title (or incipit) from the King James Version, which was only published in 1611. Therefore, Tallis, writing in the 1560s, had to wrangle with Bishop Parker's cumbersome, graceless metrical translation:

Why fumeth in sight: The Gentils spite,

In fury raging stout?

Why taketh in hond: the people fond,

Vayne things to bring about?

Whereas Barber's scoring is almost entirely for massed strings, Vaughan Williams's work for double string orchestra (one large, one smaller) is antiphonal. That means in the form of "call and response" between the two string-orchestra sections. The work also features a string quartet, employed both in solo parts and in various combinations, to highlight statements of different sections of Thomas Tallis's original work.

Tallis's theme (and Vaughan Williams' setting of it) call to mind expansive grandeur. That is accomplished via at least three compositional devices. First, Vaughan Williams' brief orchestral introduction, before the first statement of Tallis's theme, mimics the sonorities of a pipe organ, really.

Second, Tallis's theme is first stated entirely in dotted whole notes, whole notes, and half notes. Therefore, the music moves rather slowly. You might even say that it is "Regal."

Finally, the melody is "conjunct," meaning that, from note to note, the notes are close together on the musical staff, with no large jumps between notes. That gives a feeling of solidity or stability, rather than a feeling of "jumping around."

So, a wonderful piece of music, the "Tallis Fantasia" is. And, if you love it, you should really become familiar with Herbert Howells's solo-organ piece Master Tallis's Testament, which is Howells's homage to the "Tallis Fantasia."

No question, the "Tallis Fantasia" gets programmed often enough. However, there is another Vaughan Williams piece that is almost never heard. In my opinion, it is certainly as great a work.

"OK, John. What is this piece; and why is it almost never heard?"

The piece is An Oxford Elegy. I think there are multiple reasons for its obscurity.

One data point by which to calibrate An Oxford Elegy's obscurity is: The Boston Symphony has never performed it. Not to be outdone, the New York Philharmonic has never performed it, either!

First, you can't just buttonhole somebody who happens to be walking past the concert hall, hand him his script, and expect a world-class performance. There are a lot more great professional singers than there are great orchestral speakers or narrators. And they need to get entirely inside the music as well as the words. Sir David Willcocks and John Westbrook set the bar very high, in their 1968 An Oxford Elegy recording. They are a hard act to follow.

Trivia bit: Werner Klemperer, who played "Colonel Klink" in the 1960s WWII sitcom (I can't believe that I just typed "WWII sitcom") Hogan's Heroes, was a fantastic orchestral speaker or narrator. Check out his Schoenberg Gurrelieder with Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony. Werner Klemperer very generously supported young singers, btw.

Second, An Oxford Elegy is a bit of a downer. An Oxford Elegy is a musical setting (for Speaker or Narrator, boy chorus and men's chorus and small orchestra) of Vaughan Williams's brilliant selections from two extremely mournful Victorian poems by Matthew Arnold: "The Scholar Gipsy," and "Thyrsis."

Arnold's poems (written 1853 and 1861) recount the hyper-intense friendships among Oxford undergraduates (all of whom were male, up to 1920), and the feelings of loss and grief when such friends, for one reason or another, depart.

Against a background of gently swelling strings and soft choral voices, Vaughan Williams's speaker reminisces about late-summer afternoon outings in the country around Oxford, before the turn of the 19th century to the 20th.

If that strikes you as a bit twee or fey, please keep in mind that the world was a nearly unimaginably different place back then. No one—apart, perhaps, from H.G. Wells—could imagine the horrors of a world war, followed by a worldwide economic depression, followed by another world war, followed by… the very real threat of nuclear annihilation.

But, at a time—the beginning of the Cold War—when another war seemed imminent, Vaughan Williams cast his memory back to 1901, when he had wanted to write an opera based on "The Scholar Gipsy."

Secondly, while using a Speaker or Narrator (rather than setting the verses to be sung), of course works to make the words more intelligible, not everybody will want to sit through about 25 minutes of somebody talking to them (especially about sad things), with choruses and orchestra in the background.

Finally, and this surmise is entirely my own:

Surprisingly for mid-19th century Victorian poetry, Arnold's poems lack happy endings, at least in the sense of "Jesus will come to the rescue, and all will be well in the Afterlife."

Instead, at the end, we get:

"Why faintest thou? I wander'd 'til I died.

Roam on! The light we sought is shining still.

Our tree yet crowns the hill,

Our Scholar travels yet the loved hill-side."

I wander'd 'til I died.

Rather Existential, that. Isn't it?

I think that Jean-Paul Sartre would have rewarded that line with a thin smile.

British actor Jeremy Irons (if you have not seen his career-defining role in the 1981 ITV television production of Waugh's Brideshead Revisited, I hugely recommend it) recently recorded An Oxford Elegy. He knocks it out of the park. (I guess that is a mixed metaphor.) Jeremy Irons's version is on the Qobuz playlist.

So, just pull a hankie out of that laundry basket, sit down, and listen!

The embedded video is the only live performance I could find. It is a stripped-down chamber version. But it is wonderful, especially because the speaker or narrator, within the limitations of the staging, acts out, as well as speaks, his part.

J.S. Bach, Brandenburg Concerto 5 (1721)

Dark Horse: Toru Takemitsu, From Me Flows What You Call Time (1990)

J.S. Bach was, no question, a totally-committed Christian. As far as we know, at the top of every one of his handwritten music manuscripts, he wrote the monogram "IHS," for the Latin words for, "Jesus, the Salvation of Mankind."

And, at the end, he inscribed "SDG," Latin for "Only to Glorify God."

On the other hand, Bach eventually fathered more than 20 kids, and he had to keep the tuna on the table. Therefore, he wrote Catholic as well as Protestant music; and, secular (everyday) as well as Sacred music.

I am not enough of a Bach scholar to know what Bach might have thought about how best to solve the problem of how best to govern all the diverse German-speaking areas of Europe.

I have no idea of what J.S. Bach would have thought about the Unification of Germany by Bismarck, along the lines of Prussian Militarism.

Therefore, I have not a shred of evidence that, one quiet and peaceful night in 1722, J.S. Bach suddenly woke up in the middle of the night, woke up his beloved wife, and excitedly exclaimed:

Liebchen! I have had a Vision in a Dream! In the very far future, three hundred years from now, Germany will be completely at peace, and prosperous! Everyone who wishes to work, will easily find a job. And, in Germany, very smart professors will have long since imagined how to burn naphtha or kerosene to make a cart propel itself! Even better, the self-propelled carts made in Bavaria will be the envy of the world. Best of all, the makers of the Bavarian self-propelled carts will use MY music to sell their wonderful carts! They will have developed a means of transmitting pictures and music through the very air!

Need I say anything more about Bach's Brandenburg Concerti?

Well, I guess I can mention a couple of other things, over and above the fact that Bach's Brandenburg Concerti seem to have established the genre of "Classy-sounding Baroque music that lends an aura of exclusivity to luxury goods."

Bach was fascinated by how different cultures (e.g., French or Italian) developed distinctive musical styles. In his Brandenburg Concerti, he successfully modeled both Italian and French influences, while never lapsing into imitation.

Brandenburg Concerto 5's development took place over some years, primarily because an earlier version was written for single-manual harpsichord, but then rewritten for the two-manual instrument. There's a respectable argument to be made that Brandenburg 5 was actually the first Harpsichord Concerto, even though the violin and flute also have solos.

Self-taught Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu was influenced by the music of Olivier Messiaen. Later in life, he was also influenced by traditional Japanese music. Takemitsu's From Me Flows What You Call Time is a concerto for five percussionists and orchestra.

But rather than being a "Louie Bellson Bash-Fest," over the course of its 25-minute running time, From Me Flows What You Call Time is often sparse and understated—almost to the point of being "ambient" music, but with more structure, as subtle as that structure and the sound often are.

From Me Flows What You Call Time was commissioned for the 100th anniversary of Carnegie Hall. I therefore can't help but think that Takemitsu might have been indulging himself in an "Insider's Joke" bit of musical Pun-ditry.

That's because the flute solo that From Me Flows What You Call Time begins with strikes me as so similar to the bassoon solo that starts Rite of Spring that, in an Alternate Universe, there might be copyright-infringement litigation.

There's a long tradition of "HiFi Demo Records" with lots of percussion, such as Dick Schory's New Percussion Ensemble's famous 1958 Music for Bang, Baaroom and Harp. Add to that list From Me Flows What You Call Time. It will give your tweeters a work-out.

I can't help noting that Takemitsu specifies that the five solo percussionists enter the hall only after the flute solo. Furthermore, each solo percussionist wears a pocket square in a different color. It's a Buddhist thing. Ya cain't make stuff like this up.

12. Carl Orff, Carmina Burana (1936)

Dark Horse: Samuel Barber: Knoxville, Summer of 1915 (1947)

Carl Orff's Carmina Burana is one of those loud noisy pieces that I think get applauded far beyond their merits, for the simple reason that the audience gets amped up, and they want to make their own contributions to the noise. The Rhode Island Philharmonic presented Carmina Burana decades ago, and at the end of it, the audience pretty much exploded. I have never heard anything like that audience response (to a classical concert) since.

Carmina Burana's bombastic pomposity makes it a very easy target for parody and satire. The chorus's opening phrase addresses Lady Luck, the Goddess of Fortune. Therefore, "O Fortuna!" gets parodied as "Gopher Tuna!"

James Agee (1909-1955) had a difficult and comparatively brief life. Born in Knoxville, Tennessee, his life was upended at age six, when his father was killed in an automobile accident. Thereafter, Agee and his younger sister Emma were sent off to various boarding schools. Agee was a member of the class of 1932 at Harvard. Upon graduation, he went to work for Time, Inc.'s magazine Fortune. In 1934, he published his only volume of poetry, Permit Me Voyage.

James Agee

In 1938 Agee wrote a brief prose piece, "Knoxville: Summer of 1915" that Samuel Barber later (1947) set various parts of, for soprano and orchestra.

Agee later participated in the writing of two of the most famous films of that era, The African Queen, and Night of the Hunter. He was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize (in 1958), for his autobiographical novel A Death In the Family.

Agee's reputation as a writer is usually thought to rest upon A Death In the Family and his Depression-era journal Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. But it cannot be doubted that Agee was one of the most important English-language art-music lyricists of the 20th century. That is, as long as one judges only by quality, and not merely by quantity.

Agee's prose piece is a nostalgic memoir of his last memories of having an intact family, before his father's death. The narrator's perspective is usually that of an innocent child; but, at times the narrative voice seems to be that of an adult.

Agee wrote, but Barber did not set: "We are talking now of summer evenings in Knoxville, Tennessee in the time that I lived there so successfully disguised to myself as a child."

Samuel Barber had a very strong reaction to Agee's prose piece, saying in a 1949 radio interview: "I think I must have composed Knoxville within a few days... You see, it expresses a child's feelings of loneliness, wonder and lack of identity in that marginal world between twilight and sleep."

Here's the next-to-last note that Barber set:

We all lie there, my mother, my father, my uncle, my aunt, and I too am lying there.... They are not talking much, and the talk is quiet, of nothing in particular, of nothing at all. The stars are wide and alive, they seem each like a smile of great sweetness, and they seem very near. All my people are larger bodies than mine, ...with voices gentle and meaningless like the voices of sleeping birds. One is an artist, he is living at home. One is a musician, she is living at home. One is my mother who is good to me. One is my father who is good to me. By some chance, here they are, all on this earth; and who shall ever tell the sorrow of being on this earth, lying, on quilts, on the grass, in a summer evening, among the sounds of the night. May God bless my people, my uncle, my aunt, my mother, my good father, oh, remember them kindly in their time of trouble; and in the hour of their taking away.

"And who shall ever tell the sorrow of being on this earth" definitely calls for a hankie.

Nashville native Dawn Upshaw's recording remains my choice—it was awarded the 1989 Grammy Award for Best Classical Vocal Soloist. And I always check out all the new releases.

Many of which I have turned off after less than a minute, because the soprano's English diction was jarringly non-American. Knoxville: Summer of 1915 is not improved upon by employing a singer who sounds like a BBC Radio newsreader, or a French schoolmarm teaching English, or an "opera singer."

The first word to be sung is "It." It should be pronounced: "It." If somebody cannot manage to say "It" like an American, they should find something else to sing.

Instead of singing, " 'Eeeet' has become the time of evening… ."

That's all for now, Kiddos! Any outrageous statements are entirely my own, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of Positive Feedback.

Pax, Lux, et Veritas,

john

Drawing by Bruce Walker