Republished from January - February 2021

I wrote about Jared Sacks and Channel Classics this past fall, focusing on several recordings which I find treasurable (HERE). Today, I'm returning to share a further conversation from this past December in which Jared and I talk about his recording philosophy, his work with some of the artists on the Channel Classics label, and how this all came into being for him.

Jared has been a very visible champion of high resolution DSD recording for many years. His recordings for his label, Channel Classics, have been regularly recognized for their superbly natural sound and tremendous musicianship. Over 30 years, Channel Classics has become one of the defining, truly independent classical music labels. And with this, Jared has become surrounded by a fiercely loyal family of artists, including Rachel Podger and Brecon Baroque, Iván Fischer and the Budapest Festival Orchestra, Florilegium, Ning Feng, and the Amsterdam Sinfonietta, all of whom record with him regularly. As I talked with Jared at greater length, I came to understand some of why these artists wish to work with him.

RUSHTON: You have quite a number of superb artists recording with you on your Channel Classics label. How have you developed such a family of artists to work with?

JARED: I've been very lucky to work with these musicians. When you are part of the recording process, you see the musicians, you have the chance to meet them. The day I can't make the recording is the day I'm pretty much going to stop. If I'm not part of that creative process, it really means nothing to me. For some labels, the people working there just get the master tapes, they never even meet the musicians, they just load it up to see what happens. Its great to see a good number of other independents now also doing all the recordings themselves. To be able to be part of the process, to work closely with the musicians and to create this child, it can be very satisfying. Particularly when you get the feedback, working close together and everybody is happy with the results, then you think it's worth it, all this work you've put into it. But, it's not all musicians you can work well with. There have been some examples where you just have to stop, it's not fun anymore.

You've made a lot of recordings with Iván Fischer and it looks as though you must get along very well.

I do not have exclusive contracts with these artists. If you don't work well together, no contract is going to make it work. So I don't do that. We're all trying to help each other with our passion of music and careers.

Iván does not need that of course, but I'm honored to work with him even though his schedule is unpredictable. In August we did the Brahms Third and the Second Serenade and I sent him my mix maybe a month ago, and you know… well maybe with the lock-down now, maybe he'll have the time, but we'll see. I never know when he'll have the time to listen, but then all of a sudden I'll get the email with a list of small things he wants me to look at. He doesn't warn me. I can never plan the release date because I never know when he'll have the time to do the listening.

When recording with someone like Iván Fischer, I've gathered that you prefer when possible to record movements in full single takes, rather than bits and pieces and then stitch it all together in post.

Absolutely, absolutely. With Iván it's very clear. We always do a movement at the session. He comes into the recording room to listen. And half the orchestra wants to come in, too, or however many we can fit into the room. I work with a lot of orchestras, and it's really only his orchestra where the musicians are very, very attuned to coming and being part of the process, which is very great. He listens, he makes comments, and maybe he'll listen again with the other musicians out of the room. Then he'll go to work with the musicians for a good half hour, and then we will record the movement again another two times. And then I'll look at my list for still other things we haven't got, which is usually very minor, maybe five or six things.

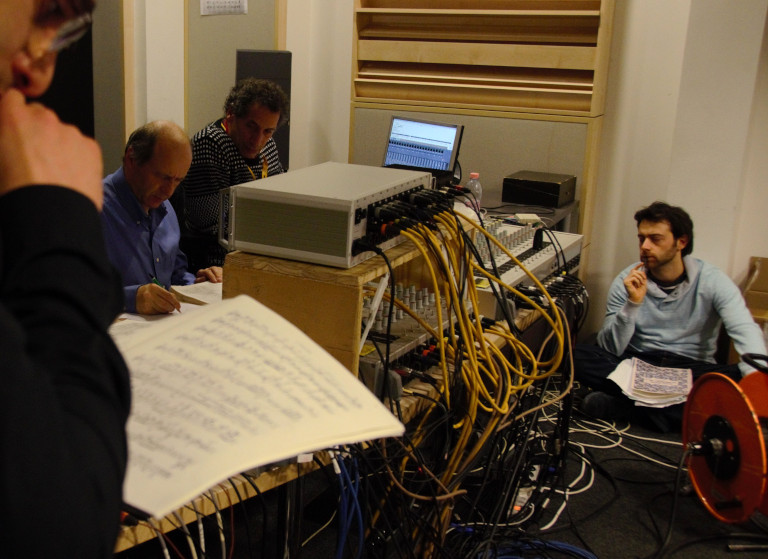

Iván Fischer and Jared Sacks reviewing recording session of the Mahler 3rd, with members of the orchestra.

Of course, the orchestra has usually been on tour with that piece for five or six concerts. And then they come back to Budapest and I'll be waiting for them. So they've already had a lot of playing time with the music. But still, you don't really get into the depth of the score without this rehearsal time. And that's what makes the Budapest Festival Orchestra special.

This is probably one of the last orchestras to record in recording sessions rather than in live performances. And Iván, like I do, really believes in recording sessions. I mean, a live concert is fine, it's the emotion, the people clapping, "wasn't that a great concert..." But if you go back to listen, well… a lot of little things.

Plus in concerts I can't put the microphones where I really want to because of the people in the hall. In a session I can quickly move something, which I can't do in a live performance. If you've been recording in a hall for 20 years, you get to know where to put mics after a certain point. But still every time, depending on the music and how thick the orchestra is, things are never the same way twice. And, Iván really enjoys the challenge of really getting into the depth of the music, every little detail. And you can't really do that in concert.

I've taken time now to watch a number of the YouTube videos by Iván Fischer where he talks about the score for music he's conducted, and listening to him talk about Mahler is just incredible.

Iván is a very intellectual conductor, not the flamboyant personality of many others. He used to have a house in Amsterdam and I'd go to his house with a camera and say, "Okay, Iván, let's talk about for instance Mahler 4." And he'd sit there for one minute, wouldn't say a word, and then he'd say, "Okay." And then here the stuff comes out from where I don't know. He just starts, and he plays something on the piano, jst, jst, jst… And it just comes out in a stream. To me, he is a savant.

In Budapest, I've been with him in his dressing room in a break when he had to conduct Mahler 3, and we'd been sitting there talking about who knows what. Then a staff member walks in and says, "Iván, the whole hall and the orchestra are waiting for you." (!!!) And he puts his jacket on and goes running out there, I also go running out to sit in the hall. And from memory he conducts the whole of Mahler 3. He's just amazing, and it's such an honor to work for him.

Iván Fischer in recording session for Mahler 3rd with Budapest Festival Orchestra.

I've also been listening to a lot of Rachel Podger's recordings and wrote recently about "Joyful Ventures with Bach" (HERE), she brings so much joy to her music and I just love it.

(Laughing) Well, she doesn't play like a Baroque player, either. She plays very free, with a lot of freedom, a lot of expression. And she's not afraid of adding a bit dance, of vibrato sometimes—not this introverted Baroque style that some of these European players are using. So, it's a pleasure working with her. Actually, I just spoke with her about an hour ago. We'd been talking about recording some unknown Mozart pieces that were never finished. We've had to cancel twice already due to Corona this year. I was willing to go into quarantine for two weeks, but in the end I did hire someone else to do the recording for me (which for me is the first time). I know the church where we'd do the recording venue and I told him how I was going to do it. He had some other ideas about the sound, and so I'll have to do some work on it to make something out of it.

This is a good segue. Would you talk a bit about your recording philosophy. What's important to you in your recordings and the sound you want capture?

At the end of the day it is the feedback I get from people listening to the recording, and they're talking about emotion. When making a recording I'm thinking to myself "I'm sitting on the fifth row." I'm not sitting on the twentieth—it's all nice but simply no emotion, no dynamics, more music for the masses. You know, I don't want to be so close that I'm hearing what you had for breakfast. And we do make the recording a little livelier than live because people are at home with their curtains and their sofas and what not.

But I want to hear the relationship between the direct sound and the ambience of the space. I want to hear the overtones. And you can only hear the overtones when it has this balance. I sometimes see pictures of other recording sessions where they have the microphone positioned right above the bridge of the violin or right above the hammers of the piano and I think to myself, "fine for audiophile, or old time jazz." Which is fine. I'm not saying I know what I'm doing; I'm just saying this is what I like.

So for me, trying to find that balance between directness and the acoustic space is the important thing. I want to capture the emotions. And I find that you can only do that when you have this distance.

This is what attracted me to recording in DSD twenty years ago. I found I could get closer to the sound source without feeling it being in your face. It was still open. It still had depth of sound. And I couldn't get this with PCM recording. This gave me more possibilities and is why I committed to recording in DSD from that point to today. (Of course, add to this multi-channel.)

So that's pretty much my philosophy, but I have a special technique I use in setting up the microphones in my main systems. There's nothing secret, I teach it to my students at conservatory, but I'm pretty much the only person using this today. It's an M-S (Mid-Side) recording technique, a figure of eight pattern using microphones mounted on top of each other. Carefully using this gives much more depth of sound when I'm carefully combining that with my main array of microphones. It gives my recordings a distinctive sound. More depth, controlled imagery, more body of sound. I guess this translates into more emotion. Combined with the artistry of Rens Heijnis here in Holland who makes by hand all the custom equipment (battery powered preamps, higher phantom power microphones), van den Hul microphone cables—it all comes together. It seems to work because people are quickly able to identify that it's my recording when they hear this.

Microphone setup for Rachel Podger's Art of the Fugue recording session.

How is this period of COVID lockdowns and the need for social distancing impacting your recording activities? How do you see this impacting performing artists?

This period of social distancing and lockdown has been terrifically hard on performing artists. A lot of the musicians are really hurting because there are no live concerts. It is the live concerts from which they are able to earn a living. Recordings help with awareness, but their income comes from concerts. So, yes, it's really difficult these days.

I made a recording with a French Orchestra in September where the distance between the conductor and timpanist was 19 meters… Actually turned out OK but difficult for everyone.

I did a recording yesterday. Everyone took a quick test for Corona and as long as everyone was negative, we could record. And with regular sitting. I've been able to do some small things like solo piano, but even that I can't do now because they've literally closed the halls completely with a new lockdown.

I made a recording in October that I've just finished editing, and it's going to be fantastic. It's the Schubert Winterriese, but not with piano and voice—with a string quartet. And it is so much nicer. I've done three Wintereisses already on piano (two with forte piano). This one with string quartet, the Ragazze Quartet, I'm really looking forward to releasing. It will do quite well. There were only five us in the hall doing the recording, and no one else, so there was no problem at all. But everything is shut down as of today.

But actually, the download site NativeDSD and Channel have done alright this past half year because everyone's been shut at home with nothing to do. They're buying all these high end files!

(At this point, some members of the team stick their heads in the door to say they're finally going home. Jared explains…)

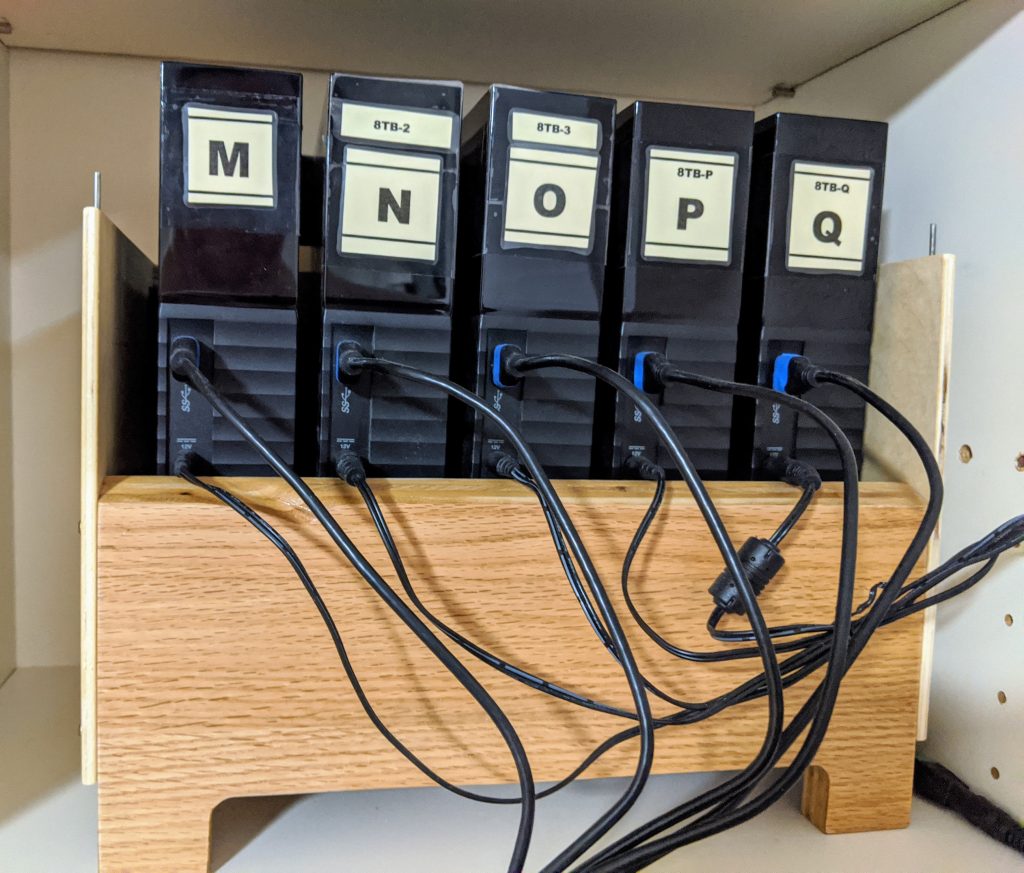

We've been spending a lot of money to get a download manager installed. I don't even want to say how much this costs, but we're now at the final stages waiting for final approval on our implementation to ensure there's no risk of hacking or malware being introduced to the servers. They thought the approval would come in today but apparently it hasn't.

Files are getting so large today with DSD256, DSD512, and five-channel. We've got to have a download manager because with the files being so large, it's relatively easy for some network interruption to occur and people don't get their download finished. If it doesn't go through, people start their download all over again. This is not only poor service but it's costing us a fortune because we pay our serving hosting provider for the transfers per megabyte. We clearly can't make any money that way, so we can't get it up fast enough.

You've long championed the superiority of DSD over PCM. What difference do you hear?

When I hear someone say "I can't hear the difference between PCM and DSD," I say, well, that's fine. Because we're living in a virtual world for audio–you can't touch it, you can't see it. You can put 100 people in front of a TV looking at the color and 100 people will see the difference in the different colors of red. But in audio, you can't see it. And it's very easy to really screw with someone's mind when you say "Did you hear that?" and they say "No, I didn't." And of course you didn't hear it either. (Laughing)

You know, I'm 67 and with motorcycle riding for 40 years, even with specially made earplugs I'm sure my high frequency hearing is gone.

What is your background and how did you come by your interest in music and making recordings?

I grew up outside of Boston and from a very early age I was already playing music, piano. I saw the French horn in junior high school and thought it looked pretty good from a distance. So, I thought, okay, I'll play French horn. I took some lessons and got pretty good at it; good enough to get into all the regional orchestras. And then I went to Oberlin for two years. I was conducting, I was composing, playing piano, and I was the director of the classical department of the radio station. I spent many hours listening and playing music from their 20,000 LP collection on the radio. I even did a stint over spring break working at a classical station in Boston called WCRB. So, I got into the listening and the whole technical aspect. I didn't think further of it.

After my second year at Oberlin, I got a summer job to play in a summer school orchestra in Switzerland. At the end of the summer I was invited to stay on to play in their orchestra. There was nothing really drawing me back to Oberlin, so I never went back. I never even went back to get my trunk of clothes. I left it at the radio station and I'm sure that trunk is long gone.

So where did you learn your craft of recording music?

I was in Switzerland for a year and a half but noticed that my social life was just a zero. Swiss girls are pretty conservative, and I had a lot of hair, curls, and a beard. I looked more like a terrorist than anything when I look at the pictures now. So with nothing happening, and at the age of 18 or 19, I had a chance to come to study in Holland because I'd played on a job with the first horn of the Concertgebouw while I was in Switzerland. He offered to help put me into the conservatory in Amsterdam because I'd already had those two years in Oberlin. So I got my degree here in Holland. In the meantime I started playing with orchestras here, and I just never left.

I was able to buy a house on a street called Kanaalstraat (which is where the name of the Channel Classics label comes from). We had at this house an attic that had been used by a restorer of paintings for the Rijksmuseum, and his father, also a restorer of paintings, had the roof extended double high. So, it was a huge space and I could rehearse there with my chamber music ensemble. And I brought in a little grand piano, and people started asking if they could give a concert here. And I thought, oh, this is a nice idea. And I built a balcony, because it was up high, and I was able to buy up some old chairs that the Concertgebouw was selling off.

So, this was in 1983 and people were hearing about this space, and we were having chamber concerts here. And I thought I should record these concerts. So I bought a couple of simple AKG microphones and a Tascam tape recorder with DBX noise reduction. People kept making concerts and I kept recording them. By '85 I found I was really enjoying this; I liked the technical part of it.

Around 1985-86, Sony came out with what they considered a consumer digital recorder, called the F1 (or 601). It was meant for the consumer; it was either this or you bought their really expensive professional machine, which was out of the question at that time. With this consumer machine, you recorded to a Sony Betamax video machine. You couldn't edit or anything. You could record and you could play back, but that was about it. But at least I was making the possibility of recording digitally by 85 - 86.

And in this attic space, people kept coming to make concerts and to have demo tapes made. I bought 20 Nakamichi cassette decks that I could link up in tandem and, with the press of one button, I could duplicate demo tapes for the musician.

And I decided, actually, I like this better than playing in an orchestra. Not everybody's made for performing in an orchestra.

So, I gave my notice and I played my last concert performance in 1987. And I went around to all of the recording studios in Holland and I said, "Listen, if I buy the professional Sony equipment needed, would you consider coming to me to get the master tape made that you need to send to the CD manufacturing plant to get your recording made into a CD?"

And I got all these letters of intention. With these, I was able to borrow 175,000 Guilders to go into business for myself. My contact at Sony asked me, "Are you sure you want to do this?" And I said, "Well, yeah." I'm an American, I didn't think about risk. You just do it.

And I did. In the first year I was up there alone and I got some important companies like EMI and Dutch companies because they needed to have their master tapes with all the right coding inserted for the manufacturing plants to get their CDs made. And I was the only one outside of Philips who did this, and Philips was only doing this for their own recordings. So, before I knew it, in two years I had 24 people working with me. And I moved, of course, down the street and I had two editing suites, and they were working day and night just to make the master tapes. Those were the golden age of CDs, of course.

In the meantime, I started making more recordings in that studio space in my house. And then people asked me for help making LPs. And then I started recording for other labels. And I thought maybe I should start my own record label.

That was in 1990. And I didn't know what I was doing, of course not. But, I have good ears. I'd played for 15 years in orchestras and I had that perception of how it should sound. And I enjoyed the technical side. That's how it all started, pretty much. I stopped playing the horn and I just did full time with the studio.

Of course the first years it was just incredible because it was the golden time for CDs. But by 1994, the technology had progressed far enough that people didn't have to come to us to do the mastering needed to send the digital tapes off to the CD manufacturing plants. They could do it themselves; they could put in the PQ codes (the start stop markers for the CD player to read to know where each track begins and ends) which you needed to have for mastering. We were getting fewer and fewer clients, and I was focused on the studio and the recordings I was producing.

So in 1995, I sold that contract production and distribution part of the business and just focused on the record label (Channel Classics). I paid back all the loans with the bank and started working on the basis of "if I don't have the money, then we just don't do it." That's what I've been doing since then. And that's why, at 67, I'm still going strong.

Over five years ago you founded NativeDSD in somewhat of a return to music distribution but with file downloads of music originally recorded only in DSD, DXD, or analog tape. It appears that you are adding more labels at a steady pace. Recently I believe I've been seeing more and more Harmonia Mundi recordings showing up.

Oh, absolutely. With the younger recording engineers buying the Horus A-D converter from Merging Technologies, we're seeing a lot more recordings that meet our criteria for inclusion on the NativeDSD site. And, we're finally close to getting on board a Japanese label that has been around for a long time with a catalog of over 200 DSD recordings.

When Harmonia Mundi was taken over by this Belgian company, they stopped the American company and we thought this was going to be the end of it. But the new company sees the financial value in making the extra effort of recording in DSD in both America and Europe, which I'm glad to see. We hope to see more DSD recordings coming from them.

You know, seven or eight years ago I was one of the last ones pushing DSD. Then Andreas Koch and Meitner came out with the DAC that actually processed native DSD without first processing to PCM. So I thought to myself, aha, and I was the first one to offer on my site DSD downloads. Now NativeDSD offers recordings from over 70 labels that were all recorded originally in either DSD, DXD or analog tape.

If people have a bit of respect for what we do, they won't copy them and pass them along to friends. But people will give their files to others; they always do. But perhaps the sharing of the files will have the upside of encouraging people to look at acquiring more. The bigger challenge comes from the commercial pirating sites. There's one in Russia that we simply can't touch to do anything about their pirating. But, what can you do?

The next exciting thing I see for the future is to sync video and DSD audio in live transmissions. You'll need good bandwidth to do this. But Andreas says he already has a device that can do that. So, this will be coming down the road.

I want to be mindful of the time. I really appreciate the time you've given me to chat. I've enjoyed it a lot. Thank you.

My pleasure, my pleasure... Listen, you're a dying breed, you know. (Laughs) People who just enjoy listening to music and in high resolution, it's… The thing is, the younger generation, I can't really blame them or get unhappy or upset because what you've never heard, you don't miss. And they just don't have the opportunity. But I've had people just sitting here crying because they just didn't know it was possible to get so much emotion to hear something like this.

All we can do is try to convey our enthusiasm for the music and the musician, and if it happens to be recorded well, you just can't go wrong. You really can't.

Photos courtesy of Channel Classics.