Roger Skoff writes about getting the most from our audio hobby.

Many years ago, Stereophile, to get a better handle on its marketing, had a study done to find out who and how many its readers were. One of the (then-surprising) things that study turned-up was the fact that almost all (well more than 90%) of Stereophile's readers, both direct and pass-through, were male.

After that information was released, I and some of my audio reviewer friends found ourselves at CES, wondering why that might be, and two of us (who, besides being major-magazine reviewers, were licensed clinical psychologists) offered the thought that, just as men and women are known to hear differently (with women generally having better and more extended high-frequency response), it might also be that men and women listen differently.

As proof of this, they pointed out that the ladies always seem to know the words of every popular song, even the very newest ones, while we men seem practically never to learn them at all. Maybe, they suggested, it's because women tend to listen more to the words of a song than to its other aspects, and men tend to listen more to a song's sound or rhythm, sometimes giving the words little attention at all.

That would certainly explain why there are so few women audiophiles: Whether on a shirt-pocket transistor radio or on the finest High-End audio system, the words of any song are always exactly the same and, if the words are what you mainly listen to, the differences in sound between the two playback systems might—at least conceivably—go unnoticed.

It also explains why "double-blind" testing works so poorly for many audio products: Accurate double-blind testing requires the ability to identify and isolate just one single factor—a frequency; a level of amplitude; a temporal interval; or something that can be the basis for an "either/or" or "more-or-less" decision. Unfortunately, while that can certainly be done using test tones, pulses, or even brief (just a few seconds long) snippets of music, the information it provides is of little value or relation to our normal listening experience, and can often be done (and accurately quantified at the same time) with just simple electronic test equipment and no need at all for either the complexity or expense of double-blind testing.

For us to actually learn something useful from a double-blind test, we would need to do extended comparative listening to full- or nearly full-length musical selections, not just, at most, a few musical phrases. Only that could allow us to hear and judge what the products under comparison were capable of doing in terms of frequency and dynamic range, harmonic accuracy, timbre, imaging and soundstaging, transient attack and decay, and all of the other things that go into the making of the full musical experience.

And that's where double-blind testing goes astray for the evaluation of products to make or reproduce music: The first difficulty is that there's no single musical composition of any kind that encompasses the full palette of all of what music has to offer and that could, therefore, be used as a universal test piece. The second is that music, by its nature, is constantly varying in its content, never portraying, in any given moment, all of what it has to offer (if it did, we wouldn't call it music, we'd call it "white noise"). And the third and fourth are problems purely of the testing's human participants and not of the protocol, itself: People hear differently, both from each other, and even, from moment-to-moment, from themselves.

I, for example, am a great fan of imaging and soundstaging, and that's the first thing I listen for when evaluating a recording or the equipment playing it. I have manufacturer and reviewer friends, though, who listen entirely differently. One is into transient attack and decay, and that's where he focuses his attention. Another is "into" the very high frequencies, and is always listening for "air" at the top end of the music. Almost everybody I know or have listened with has something that he gives his particular attention to ("Can you hear the 'blattiness' of the brass instruments?" "Can you hear the detail of the barbs on the horsehair bows as they 'micro-pluck' the strings?" "Can you hear the size and shape of the concert hall?" "Does the kick-drum really kick?"), but everybody also has moments when, despite his primary focus, his attention drifts or is called to something else, either by something in the music or just as a part of his normal mental processing.

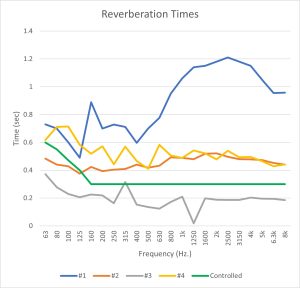

The result is that when a bunch, or even a few, people get together, whether for just social listening or as part of a "double-blind" test group, the odds are that, while all may be listening to the same piece of music, performed by the same artists in the same venue, played on the same system in the same room, at the same time, they may all—even if only because of the room's acoustics and the place they're sitting in it—be hearing different things.

That's why double-blind testing can't work for audio: To "deliver the goods," it requires the ability to identify and isolate just one single test variable and, with people and music, that may never be possible.

This same thing may also point the way to greater enjoyment of our own systems and of music in our daily lives. Knowing that different people hear things in different ways, why not try listening differently, to hear what others hear and maybe even to enrich our own listening experience? I know that I normally don't listen to the words of a song, but why not try? Maybe they're actually worth hearing, and I've been missing out on something all my life? Or why not try this: The sound of a plucked string bass has three different components—the initial pluck of the string; the spread of the sound energy from the point where it was plucked to the whole string; and the vibration of the instrument's body after the communication of the string's vibration to it through the bridge—"pluck," "spread," and "body." Can you hear all three on your system? Have you tried?

All too often, we just passively let music "fall on" us, like "elevator" music that we are surrounded by but seldom actually listen to. One non-audiophile friend of mine, when I asked him over to listen to some new cables, said—of two cables that sounded quite obviously different—that he wasn't sure he heard any difference at all, and excused himself because of his age and health. When I asked what he had been listening for, he said that there had been nothing in particular; he was just "…letting it play and keeping his ears open." Then he did something really important; he asked me if there was something he should have been listening for.

At that point, I described to him some of the things that a good system ought to be able to do—imaging, soundstaging, dynamics, transient response, harmonics—the whole bundle, and invited him to listen again, actively trying to hear as many of those things as he could. To both of our great amazement, once he knew that there was something to listen for other than just the melody (We were playing Mozart), he was, entirely without coaching and with me keeping my mouth tightly shut the whole time, able to hear and describe pretty much what I was hearing, including the differences between the two cable sets!

Try it yourself. Maybe the reason there are so many claimed "audiophiles" out there arguing about whether things sound different or not or are worth what they cost is because they listen, but don't hear. Don't be one of them!