To go reel-to-reel tape or high resolution digital? That was the question facing this basically all analog person some ten years ago. No, there wasn't a lot of tape software available at the time but the same held true for high-rez digital too. Not to mention that digital playback technology was (still is?) changing from week-to-week and the powers to be couldn't even decide on a viable format (PCM vs. DSD). They still haven't. After carefully weighing all my options—and despite the paucity of software at the time—it was time to take that leap of faith into the tape world. That ancient and long forgotten technology. And never once have I regretted making that decision!

Conceptionally, there's many similarities between reel-to-reel tape machines and turntables. For example, a reel-to-reel machine's headblock and heads are analogous to a turntable arm and cartridge combination. The tape deck's drive system is equivalent to the turntable's drive system. Lastly the output of both the tape deck playback heads and turntable cartridge require amplification and equalization. There's IEC and NAB equalization curves for 15 ips tape machines (and AES for 30 ips); there's RIAA for LPs. And both analog front-ends can be improved by changes to any or all of the above pieces.

Now as good as my tape front-end sounded, I knew those reel-to-reel tapes held even more information. But was the limiting factor the electronics, playback heads or something else altogether? Enter the Doshi Audio V3.0 tapestage. Nick Doshi's phonostage has been my reference for quite some time (more on the new V3.0 soon) and seeing and hearing his new V3.0 tapestage at some recent audio shows only served to pique my curiosity even more. Then Nick made an irresistible offer after RMAF 2016. Do I have any interest in listening to the tapestage for a month? Silly question. Or course I would. That unit was shortly followed by the review sample and current version of the V3.0 tapestage equipped with ClarityCap's latest ICW Film capacitors.

Nick also suggested listening to his tapestage with his Technics 1506 machine outfitted with a John French modded headblock and Greg Orton's low inductance, Flux Magnetics playback heads (~150 mH). The Flux Magnetic playback heads occupied as one of my best tape buddies Ki Choi refers to it, "the best real estate in the headblock;" dummy heads also replaced the two stock heads on the right side of the headblock. Another modification included specially made Tape Project's fixed tape guides with precision ball bearings with ceramic edge guides. Transparent Audio wire (in balanced configuration) was used between the headblock and his tapestage. All of these changes were designed to produce the widest bandwidth and flattest frequency response possible.

Super Analog All The Way

So why are a growing number of audiophiles getting into reel-to-reel tape tape? They all can't be all spinning their reels! For one thing, 15 ips tapes [unlike LPs] sound the same from the beginning to the end of the reel. Sadly it's an inconvenient truth that orchestral climaxes often occur at the worst possible portion of the LP. Next, all things being equal, reel-to-reel tape possess a greater dynamic range particularly when it comes to the low frequencies. Another factor worth considering is the bottom end isn't mono'd like most LPs. Nor are there any pops and tics. Tape can also—Jonathan Horwich's International Phonograph releases being one example—hold up to 32 minutes of uncompressed music. Try putting 32 minutes on a record! Lastly, there's the frequency extremes. There's just some instruments—take triangles, vibes, cymbals, tam-tams—that no matter how good your record playback setup give even the best cartridges fits.

Why did I get into tape? Simple. First was to establish a benchmark when reviewing turntables, arms, cartridges and the system as a whole. Next was having the ability to assess the quality of the tape-to-record transfers. Lastly—and I'll make no bones about it—was just plain old sonic bliss. As the late Mike Spitz of ATR services said, "Nothing sounds like tape." My first ever reel-to-reel article entitled "The Tape Project Reissue Series - Reel-to-Reel Tape: The Real High Resolution Format" (HERE) published some ten years ago now documents that journey. My foray into the tape universe began with a pro-sumer j-Corder Technics RS1500 reel-to-reel tape deck in large part because of 1) space considerations; 2) the machine was serviced and met its specifications; and 3) the machine's excellent tape pulling capabilities. Everything else—heads, electronics, wiring and even the tape path—would eventually be modified or changed.

Separating the Men from the Boys

The one and only company releasing music on 15 ips reel-to-reel tape at the beginning of my journey was The Tape Project. Ten years later that number has swelled to 30 companies! With even more companies looming on the horizon! The Tape Project catalog consists of 29 titles and overall there are roughly between 300 to 400 tapes "legitimate" tapes now available. Yarlung Records and International Phonograph, Inc. (Yarlung's recordings are also available on LP and Quad DSD; IPI on Quad DSD) represent the crème de la crème of today's new recordings on reel-to-reel tape. Add to that group many great reissues from The Tape Project, Acoustic Sounds, Opus 3 Records, Horch House, Groove Note and reel-to-reel tape is getting serious traction. No long is it just a curiosity.

The Doshi tapestage's quietness and neutrality brings out the very best from each of these 15 ips reel-to-reel tapes (30 ips too). Lately the meaning of neutrality has like several other audio terms been perverted from its original meaning. Neutral originally meant that the component neither adds to nor subtracts from the music. Neither warm nor cold. Neither euphonic or washed out. Neither pleasing nor amusical. Across the frequency spectrum. Not as used lately where neutrality often conjures up Foreigner's hit song "Cold as Ice." Not with the Doshi V3.0 tapestage.

No solo instrument better illustrates the Doshi Audio tapestage's neutrality than the Yarlung Records recording of Frederic Rosselet performing the Bartok inspired second movement Capriccio from Hungarian composer Gyorgy Ligeti's Sonata for Solo Cello. Here the Doshi Audio tapestage on this tube microphone and tape deck recording neither adds unnecessary warmth to the instrument nor does it cast the cello as mechanical sounding. As one visitor recently remarked you can even tell just how far Rosselet is bent over the cello. The cello is vibrant, rich, and wooden sounding. The Doshi's remarkable low level resolution, detail and delicacy brings the music alive. Everything down to reproducing the varying tension of the bow across the strings is faithfully reproduced. Especially with Magico's new S-Pods footers installed under the S5 Mk. 2 speakers.

Comparing true second (or safety) vs. third generation tape copies of Mark Colby Quartets (International Phonograph, Inc.) reveals even more about the tape stage's quietness and neutrality. No, the difference between the two tapes isn't that one is hissier than the other. No. The Doshi simply reveals that as good as the "normal" copy of the Mark Colby Quartet is—and believe me it is—the earlier generation is just a little better in every way. Quieter. More transparent. Additional information. Greater three-dimensionality. A little more of everything. Yes the second generation aka safety tapes are a little more expensive but worth every penny!

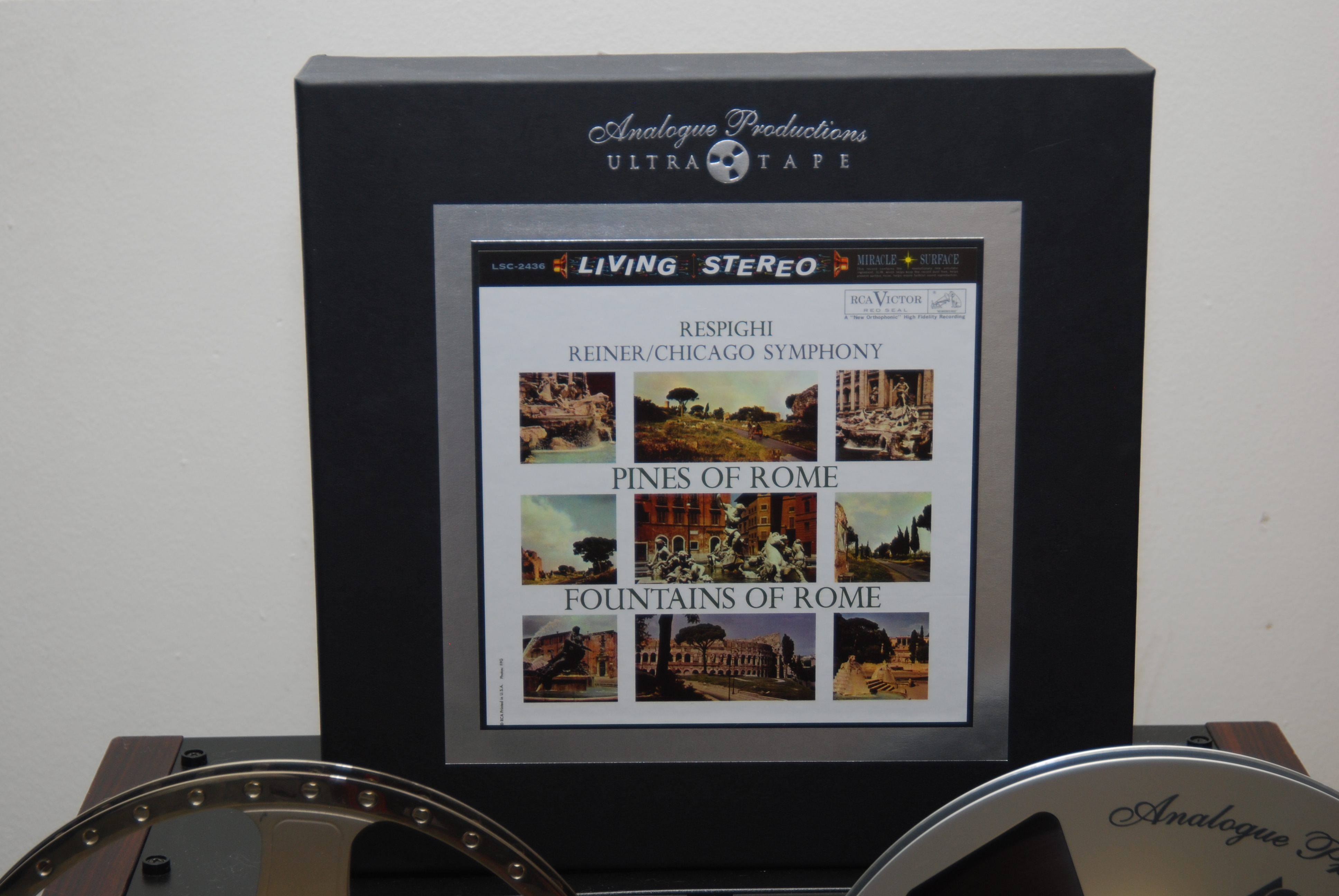

Another indicator of the Doshi tape stage' neutrality? Each and every tape has its own distinctive "sound." Some are wonderfully transparent and see through (Eric Bibb, Opus 3 Sampler tape 2). Some demonstrate better midrange tonality (Espana, Chasing The Dragon). Some have fantastic soundstaging and spatiality (The Pines of Rome, Acoustic Sounds RCA Living Stereo). Some are live in your room (Makaya McCraven, Direct copy, International Phonograph). Some are oh-so-incredibly realistic sounding (Garcia-Grisman, The Tape Project). And yet others have a fantastic low frequency foundation (Lou Harrison Canticles, Smoke and Mirrors Ensemble Debut, Yarlung Records). All these factors and more add to the distinctiveness of each and every tape that is played. By contrast, other tape stages no matter how good definitely leave to different degrees their mark on the sound.

The second movement Capriccio from the Ligeti composition Sonata for Solo Cello (Yarlung Records) also provides a segue way into the tapestage's dynamics. One word defines the Doshi's low end Doshi's low frequency: unstrained. Nothing but nothing puts the system and Doshi to a greater test than the Capriccio with its presto con slancio tempo (very quick with impetus) in the opening section. Perhaps even a touch more dynamic and solid sounding running the Merrill Audio Veritas instead of my reference conrad-johnson ART amplifiers on the Magico S5 Mk. 2s. What the Doshi brings to the musical table more than anything is just the ease, speed and control. The Capriccio—no matter how dynamic and energetic Rosselet's playing—just never falls apart.

Large scale orchestral music separates the men from the boys and no tape better illustrates the Doshi's ability to capture the dynamics of an orchestra going full tilt than Acoustic Sounds recent rerelease of the classic RCA recording of Fritz Reiner and the Chicago symphony performing Resphigi's Pines of Rome (another recently arrived dynamic blockbuster is Chasing the Dragon's Chabrier Espana!). No question the "The Pines of the Appian Way" with the Roman Legion marching down the Via Appia in the morning sun always provides the biggest challenge to audio systems. Here even the best pressing of the LP simply can't equal the power and authority of the tape. It's painfully obvious—especially on the original LPs—where the LP just hits a brick wall in dynamics and distortion sets in. By contrast on the tape, it's obvious that Lewis Layton used every dB of headroom—and maybe even a little more—that this 15 ips, ½-inch master tape possessed. The music just swells and swells and swells.

Furthermore—and no big surprise here—the Doshi V3.0 gives you the sense of space and superlative soundstaging and imaging that one comes to expect with reel-to-reel tape. Again comparing the RCA LP releases (original/Classic/Analogue Productions) version of either The Pines of Rome or Scheherazade vs. the LPs serve to illustrate these differences. Here what the LP hints at in terms of the acoustics of Chicago Symphony Hall the tape lays out in its full glory. Shockingly so.

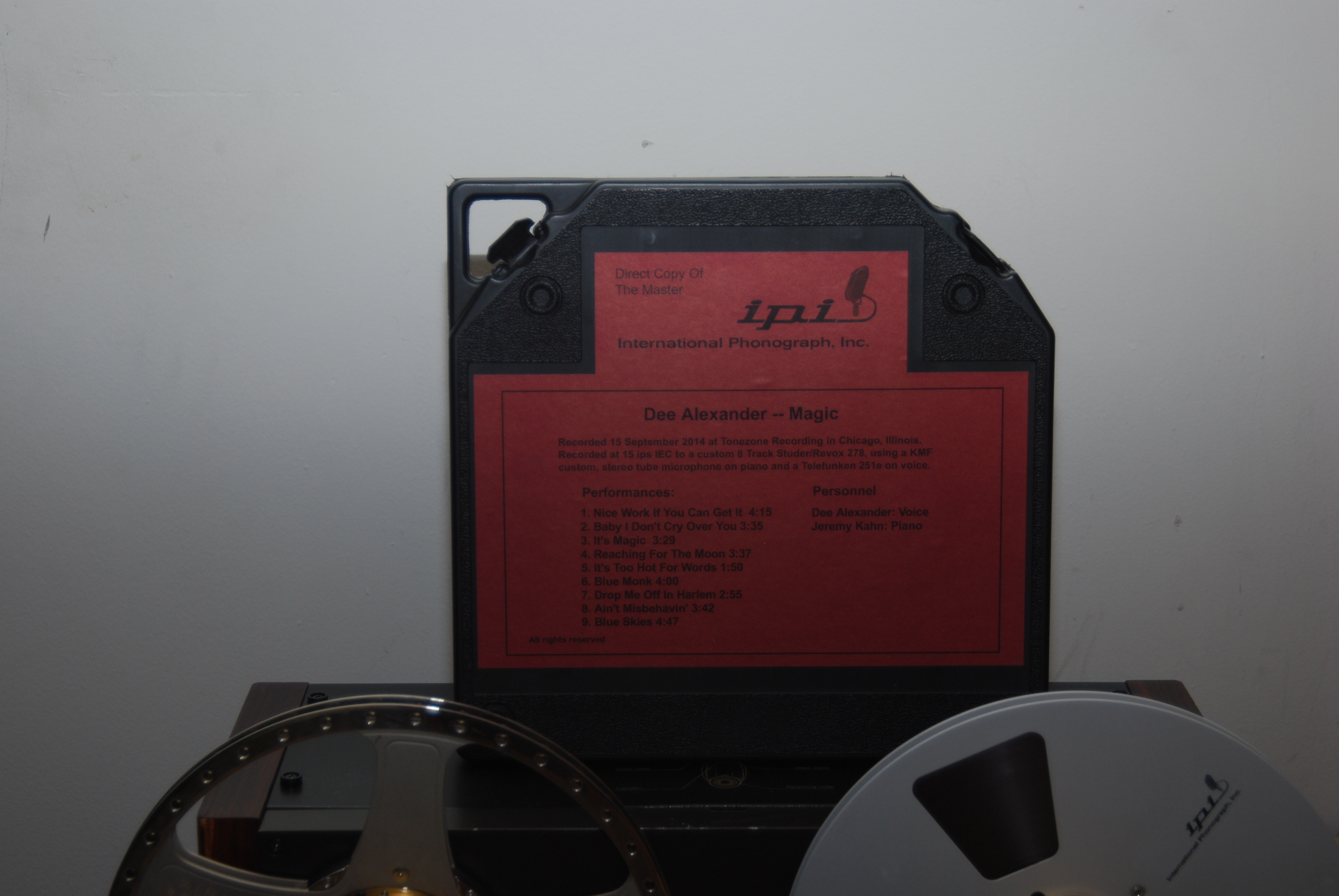

Finally, there's nothing like my 2015 Product of the Year (HERE) Garcia-Grisman or Dee Alexander Magic (International Phonograph, Direct copy) to illustrate the completeness of the Doshi's tonal pallette. First a couple of listening notes from Garcia-Grisman. "Amazing tonal recreation. Superb transparency. Stunning performance at the frequency extremes." Yes. The Doshi faithfully captures both the mandolin's ringing and the harmonic envelope surrounding the instrument. Moreso, the tapestage's quietness and resolution reveals for the first time the softest playing percussion instruments. Consequently, there's just more music and meat on the bones on my favorite cut "Arabia." Particularly when talking about the frequency extremes where the amount of information, delineation, harmonic decay surpasses the excellent MOFI vinyl release.

There's perhaps no better midrange test in my tape collection than Jonathan Horwich's recording of NPR's 2014 Jazz Vocalist of the Year Dee Alexander accompanied by pianist Jeremy Kahn (International Phonogram, Inc.). Make no mistake. Dee is no ordinary audiophile female fare and this limited edition Direct copy (meaning true second generation tape originating from the original 8-track master tape) really captures her incredible vocal dexterity as she moves up and down the scale. Take for instance the last track on the tape of Irving Berlin's storied "Blue Skies." Dee's arrangement of this "scat filled romp" was wonderfully captured using the legendary Telefunken 251e tube microphone. There's no harshness. There's no veiling. There no sense of the recording being a mechanical recreation. Only an uncanny feeling of Dee performing in front of you! A reality that escapes digital and turntable front-ends.

No Dorothy There Truly Isn't Anything Like Tape

Professional recording magazines write ad nauseum about the flaws, foibles and difficulty of recording onto reel-to-reel tape (Pro Tools being—to steal my colleague Mark Pearson's line—probably the best example of professional audio's version of a DCP [digital couch potato]). One can't help but ask after listening to the Doshi Audio tapestage operated balanced and paired with the Technics 1520 outfitted with Flux Magnetic heads whether and how much of the criticism leveled at tape is directly traceable to the tape machines electronics—even the playback heads—and not the tape medium itself?

One fact is unavoidable. Playback head gap width is far narrower than record heads and the ability to machine playback heads to those standards simply didn't exist years ago. Today, thanks to the efforts of people like Greg Orton of Flux Magnetics, the situation has changed. Coupled with the Doshi Audio tapestage, tape decks are able to retrieve more from these new and old tapes than ever thought possible (sound a little like recurring theme for analog in general?). The result is we're finding out—not unlike the situation with LPs—that those tapes were even better than ever imagined.

The Doshi V3.0 is today's hands down benchmark for outboard tapestages. By contrast, other tape preamplifiers that have come through run the gamut from tubey all the way to slightly solid-statish. The quality that really stands out the most about the Doshi Audio V3.0 tapestage is the unit's uncanny ability to get out of the way of the music. Just the music and only the music sir. The differences between recordings just has never been so apparent. Slightly closed in. Rich in the midrange. Absolutely transparent to the back of the stage. These differences are immediately apparent and unmistakable. Most importantly, the Doshi Audio V3.0 brings the listener a large step closer to the sound of real music and make that system sound like a million dollars.

Technical Highlights

Make no mistake. The Doshi V3.0 tapestage isn't another phono stage retrofitted for use as a tape stage. "Sure there's some superficial similarities between a tape and phono stage, says designer Nick Doshi, but, "moving coil cartridges and tape heads have very different electrical properties and must be treated in different ways. Tape heads," Nick adds, "have higher inductance and don't like added capacitance (in other words low input capacitance). By contrast low output moving coil cartridges are low output impedance devices and can tolerate more capacitance."

Nick began the project to design the best tape stage available and bring out the best of reel-to-reel tape some, "four years ago." The result of his effort, the Doshi V3.0, "has been in production for two years. The hallmark of the Doshi V3.0 tapestage—sonics aside—is its flexibility and compatibility with both professional and pro-sumer decks such as Technics, Otaris, Studers, Ampexes, etc. With that comes a bewildering variety of tape speeds, head inductances and outputs out there in the real world. Consequently, the Doshi V3.0 tapestage comes with both IEC and NAB EQ curves for 15 ips machines and AES EQ for Studers, Ampexes, Otaris, etc. that spin reels at 30 ips. Or a wide range of resistive and capacitive loading for the many playback tape heads. Or the headroom to accommodate the 10 dB higher signal levels of 30 ips tapes and play them without distortion.

The input stage nee "head amp" of the Doshi tape stage uses an Analog Devices IC chip. No question that the mere mention of an IC in the circuit path would raise many an audiophile's eyebrows. Nick, however, is format agnostic and chooses, "what needs to best fit the purpose and works best for the design goals." In this case, Nick opted for the Analog Devices chips because of its: 1) Low input capacitance; 2) High gain and bandwidth; 3) Low noise; and 4) Fit application. In fact, the Analog Devices chip is ultra-quiet with measured noise levels on the order of -100 dB.

Eight vacuum tubes including two JJ ECC99s (line driver output) and six RFT (or other NOS or NS when available) 12AT7s (2 X phase splitter; 2 X IEC EQ amplifier; and 2 X driver/NAB EQ amplifier and driver) are used in the tapestage's circuit. Separate IEC and NAB equalization sections serve to optimize the tape stage's low frequency response. ECC99 (12BH7s can also be substituted here) driver tubes were selected in part because of their low output impedance (the tapestage's output impedance is less than 150 ohms (balanced) or 250 ohms (single-ended with the same drive capacity) allowing the tapestage to drive any length interconnect cables. Nick chose 12AT7s because they, "provide the needed gain with low input capacitance and low output impedance." The head amplifier was designed to provide approximately 30 dB of gain (adjustable, via jumpers on the board and a rear panel switch). This gain, coupled with high signal-to-noise ratios allows the use of passive shelving type low frequency equalization allowing for the preservation of gain/phase relationships through the audio pass band. All equalization is all done passively and Nick adds, "not in feedback loops so as to preserve dynamics and phase relationships."

The design of the head amplifier, with discrete class A output drivers (essentially a 5-watt power amp), imposes a higher current demand on the power supply. Other changes in the separate outboard power supply include the inclusion of a negative (30 V) supply rail for the tail of the phase splitter section. These changes required the redesign of the custom power transformer and a general beefing up of the components.

Nick personally auditions each and every part that goes into the tapestage. For instance, after much testing, Nick chose to go with 0.1% tolerance low noise Vishay and Caddock resistors in the head amplifier. The tube section features passive parts from Kiwame. The Doshi V3.0 tapestage (as well as all 2017 Doshi Audio products) use ClarityCap's newest ICW CMR film capacitors. Clarity's new metallized polypropylene capacitors feature copper litz lattice endcaps instead of the more conventional Tin-Zinc spray process. According to Clarity, the Tin-Zinc oxidizes during the deposition process producing grain boundaries across the conductive surface that joins the metallized film layers. Transformers are custom made by Toroid in the US. Tube sockets are machined teflon with machined OFC copper pins.

All the guts of the tapestage are housed inside a heavy duty, 14-gauge stainless steel chassis. Nick chose stainless steel because of the metal's high self-damping factor, strength and non-magnetic properties. A Corian top plate serves to mass damp the chassis as well as acting as a support for the legs. Iso-damp isolation grommets are used on all circuit boards and tube sockets for vibration isolation. The tube sockets are made from Teflon with gold plated connection pins. All wiring is point-to-point.

The Doshi's front panel features a mute switch, VU meters, switchable EQ curves (IEC/NAB/AES) and level/HF EQ. At first, the mute switch seemed a little extraneous; my reaction, however, changed over time. How many times does the music end but there's still tape left on the reel and you forget to mute the preamplifier? Then one spools up a new tape and suddenly there's those not so friendly tweeter tape birdies. Thus, the tapestage mute switch served a useful purpose when spooling up new tapes. The meters serve two purposes. First, they will tell you how much signal is on the tapes being played. But more importantly, the VU meters are used in concert with the calibration tape to adjust and optimize the performance of the tape machine and the tape stage. Meters have been calibrated to show "0" VU for +4dB (@1 Vrms). Units can also be specified for 0/+4/+8dBm corresponding to the reference fluxivity of the users choice (typically 250/320/355 nW/M). +4/250 is stock.

Connections for tape heads to the tapestage, for the tapestage to the power supply and preamplifier, as well as adjustments for head loading, gain, LF EQ are located on the rear of the unit. Both XLR or RCA connections are provided for the playback head and for the connection to the preamplifier. The Doshi V3.0 tapestage provides three loading settings for matching to different tape heads. The first two settings work with the vast majority of tape playback heads out there. The lowest loading setting works best with very low inductance heads. (see instructions on choosing the right settings). The low frequency EQ setting is a "shelving type EQ" and functions to smooth out the low frequency "head bump" and frequency response.

Low and high frequency response is optimized with an MRL calibration tape. It's difficult to "directly" measure upper octave extension since the MRL tape's test tones only extend to 20 kHz; low end frequency response depends to a large extent on tape transport and shielding around heads. But Nick has measured with the Flux Magnetics heads flat down to 20 Hz.

In addition, the tapestage can be ordered with an optional headphone amplifier/jack. This amplifier will drive any headphones >20 ohms and "will," according to Nick, "work into a dead short without damage." For studio applications, the tapestage can also be ordered with balanced output transformers.

Just a little about the new tape deck used in the review. The Technics 1506 tape deck (Nick's tape stage was also used with my old Technics RS1500 equipped with Nortronics heads) came equipped with low inductance Flux Magnetic playback heads (~140 mH) allowing for the flattest and most extended frequency response. There's, however, one catch. (Isn't there always?) It's hard to take advantage of low inductance heads because as Nick pointed out, "the heads low output (1 to 1.5 mV depending on speed and reference level)." Thus it's necessary to have an ultra-low noise and high gain tape stage (about 50 to 55 dB) to fully realize the low inductance head's capabilities. In fact, these heads are normally only used with greater signal output ½-inch tape. Why weren't low inductance heads more widely found in tape machines if they gave the best frequency response? Nick feels an overriding reason was money. "Tape machine manufacturers wanted to decrease costs of internal electronics." There are of course exceptions to the rule such as the Studers that used step-up transformers to amplify the head output. On the other hand, the penalty to be paid among included issues in low frequency response.

Wiring between the machine's playback heads and tapestage is just as, if not more, critical than with phono cartridges. Here Nick chose to use Transparent Audio's specially developed, low capacitance AES/EBU cable between the playback heads and tapestage. In addition, the playback head was wired in balanced mode to the Doshi Audio tape stage. Transparent Audio Gen 5 XL as well as Audience's latest Au 24sx interconnects were used interchangeably between the tapestage and the cj GAT series 2 preamplifier. The Transparent offered a little more information particular at the frequency extremes while the Audience a little more midrange presence.

Specifications

- Weight: 38 pounds

- Gain: 54 dB

- Hum and noise: at least 80 dB below 1 V

V3.0 Tapestage

Retail: $15,995

Doshi Audio

Nick Doshi