[The Boston Symphony Orchestra has been entangled with Tanglewood for decades. This outdoor setting of historical (for America) lineage has seen more than its share of great orchestral works over the years, thus affirming the blessing of the original benefaction given by the Tappan family back in 1936. John Marks, editor and writer at The Tannhauser Gate (http://www.thetannhausergate.com), writes of his very recent experience with the BSO at Tanglewood, and gives us some glimpses into the audio arts going on behind the scenes.

Classical music in a lovely and memory-filled scene, undergirded by generosity...a very moving combination!

Do be sure that you try the streaming audio link from the BSO online, at the link that John provides at the end of this article. Listen, and be blessed....

Dr. David W. Robinson, Ye Olde Editor]

Photo © 2016 John Marks

On Sunday, August 14, the musically-astute friend I mentioned in the context of the Andris Nelsons Boston Symphony Wagner/Sibelius CD and I traveled to Lenox, Massachusetts, where the Boston Symphony makes its summer home at Tanglewood. The program consisted of Beethoven's Op. 64 Coriolan Overture (1807), his Piano Concerto 3 (1800-1801), and Schumann's Symphony 4 (1841/1851).

But of course, I could not resist indulging in audio geekery, in the process making a new pro-audio friend! Geek-bait photos, official concert photos, and a link to streaming audio of the concert, all after the jump!

In 1936, Mary Aspinwall Tappan and her niece, Rosamond Sturgis Dixey Brooks, gave the Tappan family's 210-acre summer estate, Tanglewood, to the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Nathaniel Hawthorne had lived in a cottage in the area when he wrote a children's book called Tanglewood Tales; the Tappan estate was thereafter named in honor of the book. While there had been summer orchestral concerts in the Berkshires since 1934 (originally with the New York Philharmonic), the gift of the Tanglewood estate–in the depths of the Depression, no less–made possible a permanent home for the summer concerts of the Boston Symphony.

In 1937, an outdoor concert was interrupted by a thunderstorm. Gertrude Robinson Smith, a formidable woman who had been awarded the Legion of Honor in WWI for organizing medical supplies in France for the troops (she also took some of the first aerial photographs of actual ground combat) took to the stage to challenge the crowd to pledge funds for a permanent building. With $30,000 in pledges, the Boston Symphony (largely at the insistence of conductor Serge Koussevitzky) selected Eliel Saarinen (father of Eero Saarinen) as architect.

However, Saarinen and the BSO soon parted company. Saarinen's preliminary design was simplified and then built by a local engineer whose briefs were economy and functionality, not architectural elegance. Indeed, Saarinen himself warned the Trustees that if they did not build his costly and elaborate design, they would end up with "Just a shed." The name stuck. And the utilitarian result can be, if you squint a little, somewhat reminiscent of the baseball stadium Fenway Park.

The Shed opened in 1938, with a capacity of over 5000. The site plan also provided lawn seating. In 1959 the Shed underwent a successful acoustical re-design by Leo Beranek. Today, orchestral concerts have sound reinforcement both inside the Shed (as far as I can tell, mostly side fill to make up for the lack of side walls and therefore side-wall reflections) and for concertgoers on the Lawn, where obviously the sound reinforcement system is the main source of sound.

Photo © 2016 John Marks

The mix position for sound reinforcement for the Lawn is a small shack with roll-up corrugated metal sides. Within I found the personable and knowledgeable Gintas Norvila, an Assistant Audio Engineer for the Tanglewood Music Center. Gintas and I bonded over our respect for pro-audio equipment made by Grace Design (the audio feed that Gintas mixed for Lawn attendees originated with Grace Design mic preamps and analog-to digital converters). I just love the music stand with scores and clothespin-style placeholders.

Photo © 2016 John Marks

I was also charmed to see a Bricasti M7 stereo reverb unit, used to fatten up the sound by ear from the mix position, in that outdoor sound by its very nature is quite lossy. The Bricasti device is the black unit under the right-hand monitor speaker. Another favorite thing of mine is the Littlite gooseneck LED task light over the mixing board. You can see the rear of the Shed in the distance.

Oh, yes, there was music, too!

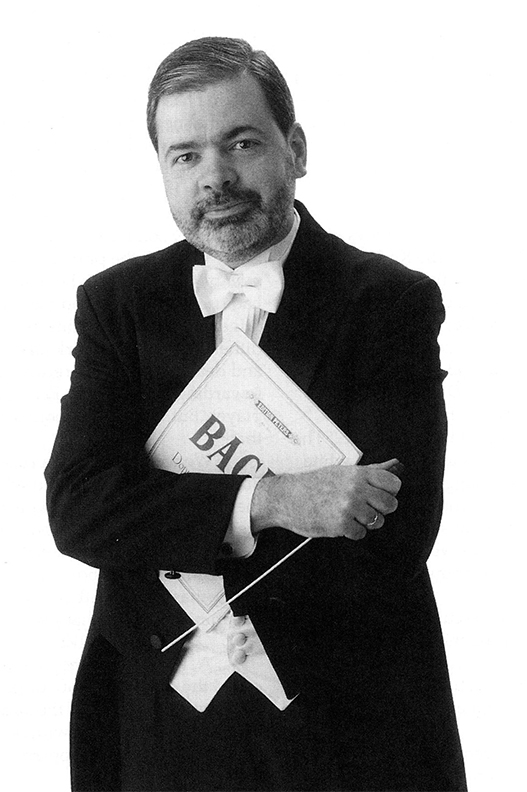

Photo © 2016, Hilary Scott for the Boston Symphony

Conductor David Afkham‘s name was new to me, and indeed these concerts were his début with the BSO. I was very very impressed, especially with his sensitive and collegial accompaniment in the piano concerto, where soloist Igor Levit at times really pushed the envelope in terms of playing at the soft end of the dynamic scale. Levit as well was making his BSO début. Both are truly excellent musicians, which made the number of empty seats rather unfortunate. It's a sad commentary on classical music's "star system" that when an unknown conductor is paired with an unknown soloist, it seems a lot of people can't be bothered.

Photo © 2016, Hilary Scott for the Boston Symphony

Fortunately, the entire concert is available for streaming at no charge, HERE (concert of 8/14/2016). Please listen to the concerto at least, and see if you don't agree with me that this is a very rewarding interpretation. If I dare say it, Levit played the concerto not as a soloist but as a colleague in realizing an entire piece of music. Indeed, Levit's interpretation sounded more like Mozart than the typical soloist's approach to Beethoven. Levit's playing often was gentle and introspective, joining with the orchestra in fully-developed polyphonic textures. But there was no shortage of forward propulsion and virtuosity when called for, especially in the third movement. A soloist who cares less about "being a soloist" than he does about serving the music–what a concept.

There might have been a lot of empty seats in the Shed, and the Lawn was very thinly populated, but the audience responded with an immediate and well-deserved standing ovation. After three curtain calls, Levit played a hyper-virtuosic encore that I at first thought must have been one of Earl Wild's études based on American popular songs. However, it turned out to be (I learned this courtesy of Levit's management IMG Artists) Salvatore Sciarrino's "Anamorfosi," which is a mashup of Ravel's "Jeux d'eau" with the song "Singin' In the Rain."

Do listen to the streaming audio–you are in for a treat.