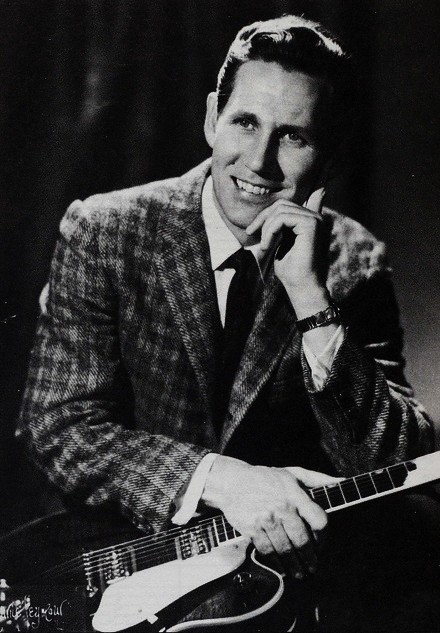

If you're a vinyl-spinning audiophile and you love great guitarists, you should listen to Chet Atkins (1924-2001). Heck, even if you don't spin vinyl you should listen to Chet Atkins. The soft-spoken man from Luttrell, Tennessee, was also known by the nicknames Mr. Guitar and The Country Gentleman. His guitar tone was sweet like honey, his phrasing as smooth as butter, and the punchy bass line that he obtained by using a thumb pick on the bottom guitar string has been imitated, but never has his sound been duplicated. Although Atkins' ability to play guitar rivaled jazz giants, like Wes Montgomery and Barney Kessell, a large number of the cuts on his albums are little more than country-tinged easy listening. However, an equal number of his cuts are technically challenging and musically engaging. Nashville was his home, and he played an important role in the city's history, as he was an enormously successful record producer during the golden age of country music. A partial list of the artists Atkins produced reads like a Who's Who of country legends, including Waylon Jennings, Dolly Parton, Bobby Bare, Willie Nelson, Eddy Arnold, Charlie Pride, Jim Reeves, Dottie West, and Porter Wagoner. He was also one of the main architects of what is now called countrypolitan, the de-twang form of country music, often filled with lush choruses and strings, that made country music palatable to mainstream audiences. Yet, despite my appreciation of his achievements, I didn't always admire The Country Gentleman, and in the next two paragraphs I will explain why.

Back in 1984 my audiophile friend, Victor, gifted me a subscription to The Absolute Sound (TAS). Like many TAS readers from that bygone era, I frequently glanced at editor Harry Pearson's famous "TAS List" of recommended LPs. Pearson, like most high end journalists of his time, was a classical-centric audiophile, hence his list primarily focused on well-recorded classical LPs. However, it also contained a smattering of rock, pop, jazz, and film music. Within the list were three Chet Atkins titles. When I bought The Other Side Of Chet Atkins and Caribbean Guitar, I learned that Pearson was recommending music that was far outside of his wheelhouse. Although both albums offer aspects of "audiophile sound," they are poor examples of Atkins' talent. All they are is easy-listening dreck. They also feature him on acoustic guitar, and I much prefer the plugged-in Atkins. And then we have the Pearson-recommended Chet Atkins in Hollywood. Mr. Guitar was indeed plugged-in on this album, but he's smothered by strings. Blech! So, thanks to a high end writer who should have stayed inside his Mahler-Elgar-Shostakovich lane, I spent two decades avoiding Chet Atkins.

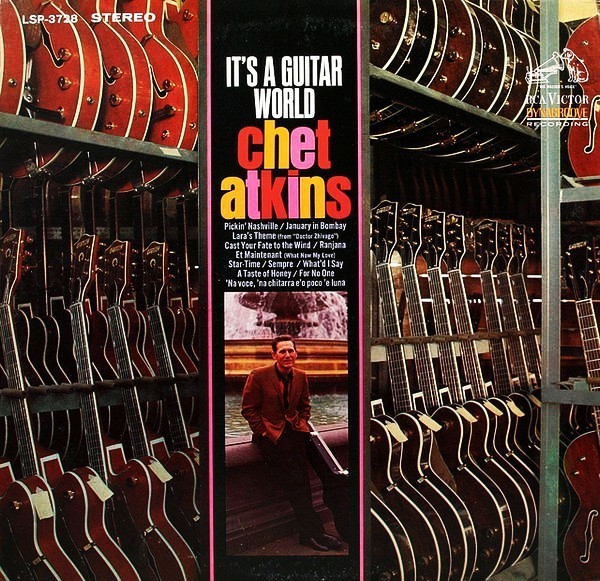

So what changed me? In the early 2000s, while attending the CES in Las Vegas, I entered a demo room where I heard Atkins' 1954 instrumental recording of "Mr. Sandman." The sound came from two small speakers with ribbon tweeters. Up until then, the only version of the song I knew was the vocalized version by the Chordettes. I was stunned, because the guitar sounded amazingly lifelike, and, unlike in the past, Atkins captivated me. Instead of hearing generic guitar picking, which is the way Atkins always sounded to me, I heard something I could connect with. I also remember having zero interest in the rest of the audio system, which for me is really unusual. I don't even recall if a sales rep was in the room. What I clearly remember, as if it were yesterday, was being alone with Chet Atkins. The feeling was euphoric, and a bit strange. All I can assume is my euphoria was the result of making a personal contact with a musician whom deep inside I knew I loved. Whatever it was, it was a breakthrough. Around the same time I was starting my collection of fifties and sixties era country records. In due time, I owned records by Jim Reeves, Bobby Bare, Eddy Arnold, Skeeter Davis, Floyd Cramer, and The Browns, all of whom were produced by Chet Atkins. So, with newfound respect for Atkins, I started collecting his RCA records, and fortunately most of them were more exciting than the records Pearson recommended. Albums like A Session With Chet Atkins (LPM-1030), Stringing Along With Chet Atkins (LPM-1236), Finger-Style Guitar (LPM-1383), Chet Atkins' Workshop (LSP-2232), Christmas With Chet Atkins (LSP-2423), Down Home (LSC-2430), Teen Scene (LSP-2719) Guitar Country (LSP-2783), Chet Atkins Picks On The Beatles (LSP-3531), and It's a Guitar World (LSP-3728) feature cuts that are downright delightful, and most of them are very well recorded. Having developed an appreciation for the electrified and engaging side of Atkins, I have no reservation calling him one of the greatest guitarists I've ever heard..

Having spent a week playing selections from sixteen different Atkins records, watching him on YouTube, and finding myself deeply moved by his passionate musicianship, I had a tough time picking a title to review. I began with Down Home, but I discovered, much to my disappointment, that the stereo mix is dreadful. Engineer Bill Porter mixed Boots Randolph's sax and Charlie McCoy's harmonica too loud, leaving Atkins' electric guitar sounding miniaturized and compressed. Also, the entire stereo LP was mastered from a mediocre dub. The mono album is mixed better, but despite some great cuts, I decided it would be better for me to focus my attention on It's a Guitar World. It features more great cuts, and the sound is much better. Recorded in 1966 and released the following year, It's a Guitar World feels a little looser, or perhaps a little jazzier and progressive than his earlier work. Adding Indian-born multi-instrumentalist Harirar Rao (1927-2013) is one of reasons for the album's slightly progressive feel. Rao came to the US in 1964, and is best known for his work in Los Angeles. When The Wrecking Crew needed a guy who could play sitar or tabla, Rao received a call. As I couldn't find personnel information for any of the other musicians on this album, I can only guess who they might have been.

It's a Guitar World opens with a country blues reimagining of Ray Charles' "What I Say." Atkins' understated phrasing reminds me of Kenny Burrell, but the guitar tone is pure Atkins. The first thing I noticed, unlike the poorly mixed Down Home, is the full-sized in-the-room presence of Atkins' Standel 25L15 amplified Gretsch 6122. It sounds textured, rich, colorful, and it's smack dab in the center. Playing alongside Mr. Guitar, off to the right, is a drummer, who for eleven seconds only taps a cymbal. This is just an intro, because when the two musicians break into a jam we are treated to some of the tastiest guitar playing that's ever graced my turntable. At this point a standup bass player joins the two, and he's also on the right. At this point we're also treated to the rest of the drummer's scaled down kit. The trio's laid-back groove gives me the impression that they could explode at any second, but like the coolest of jazz cats, they just play it cool. This coolness is just one of the elements that made Atkins an amazing musician.. Once his polite groove gets under your skin, you'll understand why he was called the Country Gentleman. This is country blues in the truest sense of the form, and the sound is off-the-charts amazing.

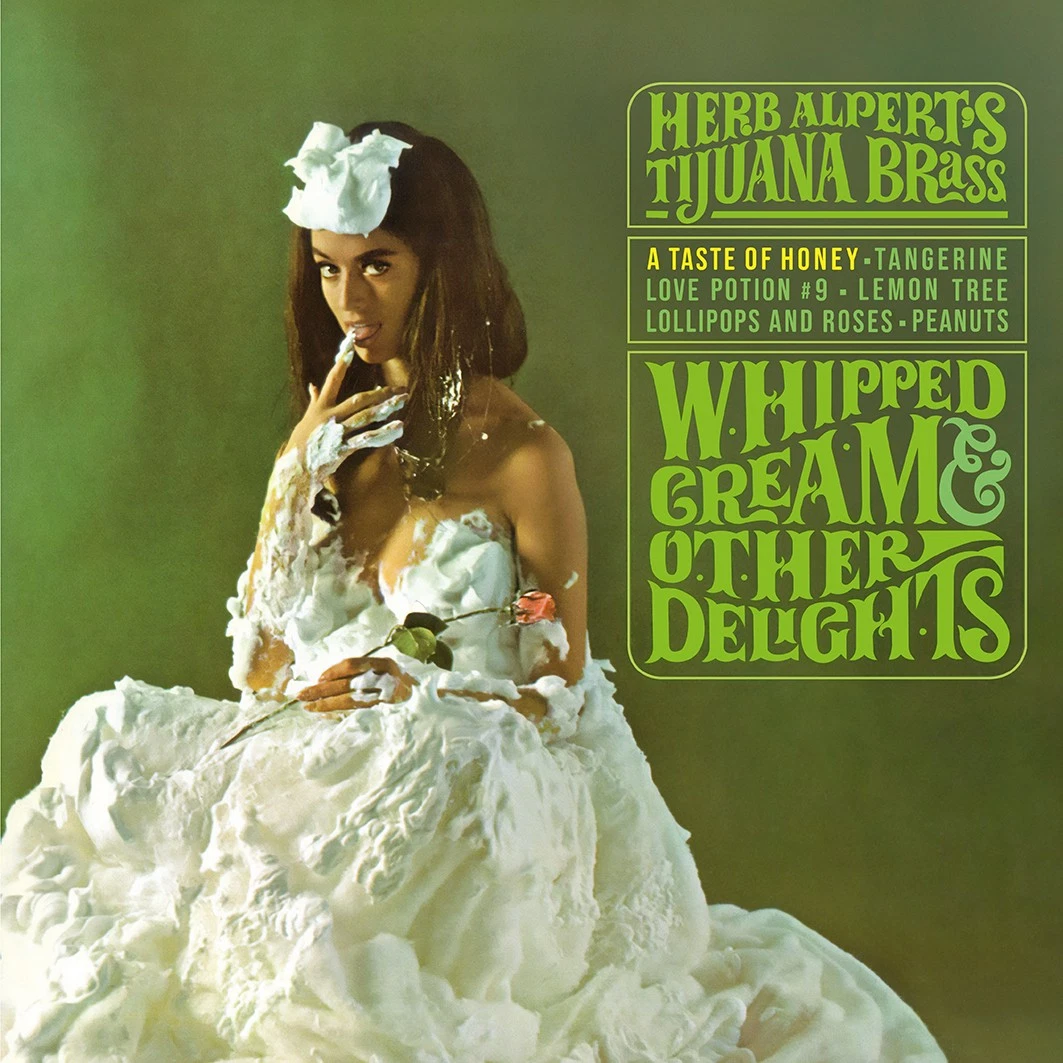

Cut four is "A Taste of Honey." You'd be right in thinking that Herb Alpert recorded the definitive version. With Hal Blaine's incredible drumming, Lew McCreary's blaring trombone, and Julius Wechter's sparkling vibes, it's hard not to consider Alpert's recording the one-and-only version. It was only recently that I discovered Chet's cool-school guitar version. Google it and check out the countless guitarists who love to play the Atkins arrangement. Some of them play it very well, but nobody matches the supreme master. The tune opens with just Chet and the drummer, who, by the way, is still sitting off to the right. It's impossible to hear too much of that Standell amplified Gretsch guitar, because it sounds so insanely delicious. As I detected a tiny bit of reverb that's coming only from the guitar, I Googled the Standell 25L15 to see if the amp features reverb. It does not, so the recording engineer had to add it, but it sounds just like it's coming from the amp! Meanwhile, the musicians play the familiar verse for 53 seconds, and it is at this point that the rest of the band enters. I say "band" because Atkins, the drummer, and the bassist are joined by an acoustic guitarist (probably Paul Yandel or Jerry Reed) who's playing on the left side of the stage. With the acoustic guitar on the far left, an electric guitar in the middle, and the drummer and string bass on the right, we have what I like to call "stereo perfection." Turning the volume up just a smidgen is thrilling, as the sound is as they-are-here believable as anybody could ask for.

Cut four is Paul McCartney's "For No One." Chet loved The Beatles, and The Beatles, especially George Harrison, loved Chet. This is a solo recording, and it's not particularly exciting, but it works as a cool-down intro to the next cut.

Side one closes with a casual jam, the kind you'd expect right before an intermission. The cut is called "Pickin' Nashville." To my ears it was intended to let the backup musicians show off, while Chet does what he often does, just pickin' around. This cut features a well recorded piano on the left. I'm pretty sure the pianist is Floyd Cramer. The sound is again excellent.

Side two opens with "January in Bombay," featuring the above-mentioned guest, Harihar Rao. Using Indian instruments was a nod from Atkins to the growing psychedelic movement in contemporary music. The tune opens with Rao banging on a tabla for seven seconds, at which point he meets up with Atkins on acoustic guitar. The tune they are now playing is the familiar "The Battle of New Orleans." However, the bulk of the music arrives at thirty seconds where we find Rao, now playing a stringed instrument called a gopi, jamming with Atkins. The two continue to play inventive variations of Johnny Horton's famous hit for the rest of the 2:58 cut. Since this cut was taken from a different session, probably recorded in Los Angeles, the sound is different. It's a little darker, or not as vivid. The sound is still good, but it's an A-rating instead of the album's overall A+++ rating. This isn't the best cut on the album, but that gopi flying out of my left speaker is exciting.

I'm not too crazy about cut two. It's another acoustic jam between Atkins and Rao, and this time Rao's playing sitar. It's not bad, but I have more interesting sitar records.

Cut five is "Star Time." It was written by Leon Payne, best known for writing "Lost Highway," made famous by Hank Williams. Based on my research, there are no other recordings of this tune, so Payne (1917-1969) must have written it for Chet. What I like about this cut is it sounds like Chet's recordings from the early 60s. The melody sounds a lot like Errol Garner's "Misty," and it's mixed in wide stereo. The drummer is now on the left, Chet's in the middle with his Gretsch, a strummed acoustic guitar is on the right, along with the bass player. It's casual, it's country, it's fun, and it sounds great. ‘Nuff said.

The sloppy bass that plagues so many of Atkins' earlier Bill Porter-engineered recordings is absent. However, the sweet midrange that is a big part of those vintage Atkins albums remains. The stereo imagery is exemplary. On both of my copies, side two doesn't quite match the sonic opulence of side one. Two recording engineers credited on this record are Bill Vandervoort and Jim Malloy. Both of these men created great sounding RCA records, but it's impossible to know which cuts were recorded by which person, so I can't state a preference for either one's work. I own more records that were engineered by Malloy, and I admire his work greatly. Anybody looking to demo their audio system with this record will be able to do so, quite well, with "What I Say" and "A Taste of Honey."

Spending a week playing cuts from sixteen different Atkins albums was a blast. However, there is one thing that I cannot hide from. It's the spottiness of his albums. All of the albums, at least to me, feature between one and five great cuts. I get the feeling that making an Atkins album was a casual affair, a party among friends, which included rounds of golf (Atkins was an expert golfer.) in between the sessions. Sometimes he was on top of his game, and sometimes he just let the tape roll despite having off moments. A great example of this is his guitar playing on "Yakety Axe." (It's the same tune as "Yakety Sax.") On Atkins' original recording from 1965 his performance comes across as little more than an uninspired I-can-do-that-too nod to his friend Boots Randolph. However, just when I thought "Yakety Axe" was just a throwaway, I found this inspired performance from 1991 (HERE). I find Atkins' inconsistencies similar to those of Nathan Milstein. On some recordings their techniques are dazzling, while on others they sounded a little sloppy.

I'm at the point where I'm running out of words to type. Chet Atkins was a force of nature. If the only Atkins you've heard are his duets with Les Paul and Mark Knopfler, in the words of the great Al Jolson: "You ain't heard nothing yet!"