You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 78

From Clark Johnsen's Diaries... The Early Annals of High-end Audio, Rediscovered

DEDICATION To J. Gordon Holt and Harry Pearson, who regrettably missed out on beholding their own antecedents, which both would have so enjoyed reading. Our modern times have been blessed with a copious amount of writing about music reproduction. This epoch began in the Fifties and Sixties with the popular magazines Audio, High Fidelity, HiFi, Stereo Review and several British and European periodicals. The American ones no longer exist, or have merged with a new sensibility defining them: video and home theater. Yet a dedicated readership does still exist for audio, served by niche publications in "the high end," both in print and online now as well. Their readership tends to place great trust in reviews delivered most especially by several veteran writers. But how does one come to discern among their efforts? Writing ability, along with its enticing entertainment aspect, might seem to be the decisive factor, although that talent does not correlate necessarily with listening ability and musical discernment, both of which are wanted for proper evaluation of audio gear by ear. But perhaps measurements, as some say, tell a better story? After all, "If it can't be measured, it doesn't exist." As some say. Reports of meter readings require no literary style, no gracious connection to the reader. Once done, that's it. No argument possible. The final word! Thus arises a defining dichotomy in current audio practice: Shall it be by the numbers, or by the ear? Nothing new here, so far? Please press on. Presently in the active high-end segment, the ear is preferred over the meter, although the latter has an acknowledged role. Measurements had formerly gained hegemony both in mass market magazines and the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society (JAES). It took J. Gordon Holt, seemingly, to throw off the shackles with his visionary, disruptive column in the old High Fidelity, "Tested in the Home." He and his approach became successful and hugely influential, but was he really the first? No, not by a long shot. There exists a preceding publishing history that even a Google search fails to uncover, at least not with any phraseology of mine. Instead I have researched in person the vast resources of the arts and music collections at the Boston Public Library, where I discovered Phonograph Monthly Review and Disques, published respectively in Boston and Philadelphia. These magazines, dating from as early as 1925, and their coverage of the sound of contemporary recordings and gear, form the basis for this original, albeit derivative article. Who would have thought that audio journalism goes back so far? The early practice/hobby was not called "audio." It wasn't even called "hi-fi," and the playback machines themselves were variously called phonographs (Edison), gramophones (Berliner) or graphophones (Columbia). Hobbyists were called "gramophiles" and "phonophiles"—in one instance even, "phonograph addicts." And it's all quite remarkable, really. Much of it reads as though written yesterday! To begin, behold the humble needle In the early days needles were easily replaceable, came in two different compositions and numerous brands, and wore out rather quickly (or, they wore the records out). The following listener appraisals appeared in Phonograph Monthly Review (henceforth PMR) for November, 1927:

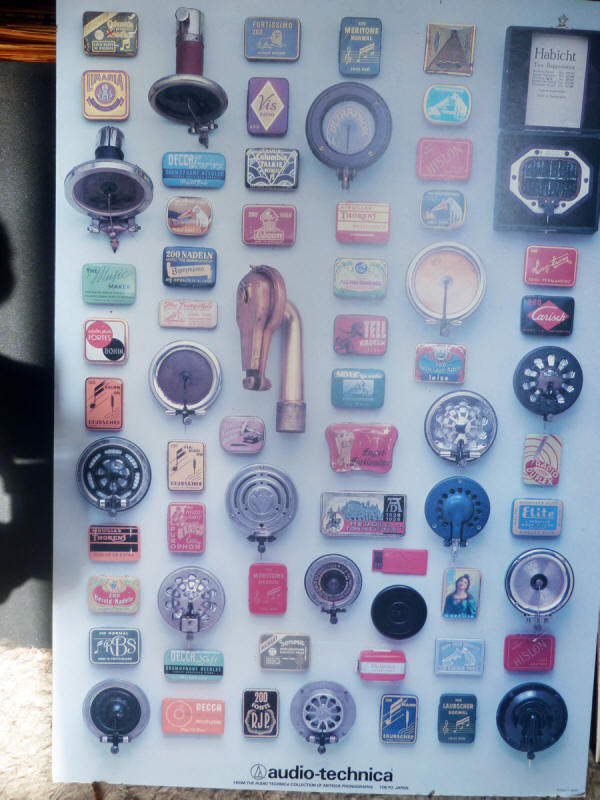

The first two are by staff writer Ferdinand G. Fassnacht, the others by enthusiastic correspondents. And we do still have needles, although they're no longer themselves replaceable. Another crucial component of yesteryear has entirely disappeared: the soundbox. The soundbox was the device that rendered needle motion into an acoustic wavefront via a taut membrane, which then would be amplified by the horn. This unit came in as many varied incarnations as the needles. This modern poster gives some idea of the astounding multiplicity.

Each make and model had its ardent partisans; there were many imports from Europe; and prices spanned an impressive range. The discussions of soundboxes resemble (pardon me here) our own audio palaver more than anything else of the era. Again, PMR, September, 1927.

There speaks a true hobbyist, one whom today would surely be labeled a tweaker. Unwilling to live with only what was available off-the-shelf, he undertook modifications of his own devising. And how did he know what worked best? How? How? Anyway, I used to read the first part of the above review out loud to the several audio clubs I have addressed. (Publishing this means I must forego any future pleasure in this regard.) I did not indicate to them the source or the date and carefully omitted any giveaway words. I simply asked the audience to guess the provenance and identity of the D.U.T. Most folks guessed "cartridges," which is close, but no one came even close to the correct date or device. Moving right along I hope this old material beguiles everyone else as much as it does myself. I read it again and again for amusement and refreshment. Now here are some further quaint appreciations and lavish encomia to enjoy:

Were these fellows crazee? After all, those were "scratchy old 78s" (as we deride them these days) that were said to sound "like an orchestra." Maybe they knew something we don't? And possibly—never shall? Even more intriguing to my mind, they showed no hesitation about modifying their systems to their own satisfaction. They showed no need to justify their decisions to "meter men," as in our present milieu, there having been as yet no meters. Audio was strictly sola auris, to coin a phrase. Even some contemporary fiction portrayed these odd pastimes A fine but neglected English writer by the name of William Gerhardie, published in 1925 a novel entitled, Of Mortal Love. I submit this telling passage:

Oh, indeed. On a proud personal note, my own earliest ambitions in audio involved constructing a Williamson-circuit tube amplifier from scratch. Likewise, in my father's modest woodworking shop I built a knockoff Karlson loudspeaker enclosure and a fine walnut turntable base and a large plywood cabinet to house everything. And so with that hi-fi system, along with a Lionel train-table already there, I completed my basement boy cave. But way before that, I had put together a whole turntable and arm out of Tinker Toys, although that hardly counts, but it did spin. Later came a lot of periodical reading at the Sioux City Public Library, especially that Holt column, which I considered inspirational. Also the fathers of two of my friends had actual component-based hi-fi systems, which enthused me further. Sure do wish I had photography of those precious, precocious junior-high efforts! And then one day long after college I moved to my current home, a three-story house ("Music in Every Room") in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, where I have lived now for fully half my life. The location had seemed propitious for two disparate reasons: it was a couple blocks from the largest animal hospital in New England (in case my beloved Mandy, a beautiful Doberlady, should require attention) and less than a mile from the Kushi Institute, American nexus of macrobiotics practice, which I was studying. There too was the first Erewhon natural foods store. The public transport was also great—short walks to the trolley, the bus, or the subway—and I was carless at the time. So imagine my delight when I finally discovered that Phonograph Monthly Review had been published down on the other side of Jamaica Plain, and their separate "Studio" where tests and listening sessions had been conducted was even closer. (In 1980, unaware of the precedent, I opened The Listening Studio, albeit downtown.) So I have taken two photographs, shown below. First the editorial offices, then the Studio building.

PMR Editorial Offices

PMR Studio Yes, talk about Tested in the Home. These were the original homes! For those interested in pursuing the story of PMR, here is a fascinating article that I terribly wish I had written: http://www.gracyk.com/pmr.shtml

|