|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback

ISSUE

57

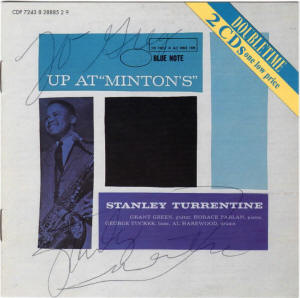

APO Continues Its Great

Run of Blue Note SACDs with Up at Minton's

Out Behind Yoshi's It was a summer night in 2000 when I saw Stanley Turrentine perform at Yoshi's, the famous jazz club and sushi restaurant in Oakland, California. My favorite works of Turrentine's were his two dozen 1960s Blue Note recordings. When he took the stage, it was obvious that Turrentine's tenor sax tone and melodic drive had lost little power since he was a young man. His playing, peppered with soul and blues inflections, is perhaps best known on CTI titles such as Sugar. He played one of those CTI tunes at Yoshi's. After the set, I tried to get backstage. I brought CD booklets for Turrentine to sign. But the stage manager told me the sax giant had already left. I finished my drink and walked into the cool night. My car was parked a few blocks away in the direction opposite Jack London Square. I rounded a corner and there, smoking a cigarette by Yoshi's back entrance, was the great Stanley Turrentine. "Nice set," I told him. Turrentine held out his hand and I shook it. I told him that his music meant very much to me over the years and I asked if he would sign his CDs. He seemed glad to, and autographed each of them with a pen I'd brought. We talked for a short while before his ride appeared. He was genuine and down to earth. I walked back to my car. A couple of weeks later, I was saddened to learn that Stanley Turrentine died of a stroke in Manhattan.

Up at Minton's Thirty-nine years before I shook hands with the sax legend, he had performed at a much different venue. On February 23, 1961, he led a group at a Harlem bar and jazz club in the Cecil Hotel at 210 West 118th Street, known as Minton's Playhouse. In the 1940s, Minton's had an open door policy for musicians. It was the site of legendary "cutting sessions" where the greatest jazz artists would jam together, trying to out-play each other during the years when bebop was invented. During those performances, the greatest musicians of the day, like trumpeter Roy Eldridge, passed the baton to a new generation. According to jazz lore, after a particularly raucous cutting session where Dizzy Gillespie outplayed his mentor Eldrige, Minton's house pianist Thelonius Monk told the elder man with the horn, ""Look, you're supposed to be the greatest trumpet player in the world...but Diz is the best." After the '40s, Minton's was no longer the scene of revolutionary change in jazz, but it continued to be a popular club for musicians and jazz lovers alike. So it was fitting that at the dawn of the '60s, a group of straight-ahead bebop musicians took the stage there to perform what would become known as Up at Minton's Volume 1 and Up at Minton's Volume 2. The rhythm team was Stanley Turrentine's working group: Horace Parlan on piano, George Tucker on bass and Al Harewood on drums. But a fourth supporting musician was added by Blue Note producer Alfred Lion: guitarist Grant Green. Lion often tinkered with working groups of the day to mix, match and create fascinating combos with the right sound and chemistry for unique recording sessions. A few months earlier, Lion had paired Turrentine with a working trio known as the Three Sounds* to produce the Blue Hour studio sessions. That February night in 1961, however, Lion simply added Green. The guitarist had recently come to New York from St. Louis. Lion's addition dramatically added to the performance. Whether he had tapped into the spirit of Charlie Christian—the legendary guitarist who frequented Minton's Playhouse and significantly advanced the use of electric guitar in jazz—or whether Green had an instant affinity with Turrentine's bluesy style, it was another case of Lion finding the right lineup at the right time with the right material. But unlike most other Blue Note sessions, this would not be recorded in Rudy Van Gelder's New Jersey studio, that was ground zero of countless recordings for Blue Note, Prestige, Riverside and later Impulse. Lion wanted to feature Turrentine in a rare live session. Up at Minton's liner notes credit Lion as saying, "The whole session was a pleasure. Everyone was in the best of spirits, Teddy Hill [the club manager hired by founder Henry Minton] was very cooperative and it was a Thursday night. The room was packed." Indeed the voices, clanking glassware and laughter of the crowd are the first audible sounds on the recording. As Up at Minton's fades in, a female voice can be heard saying, "Well one thing you know about 'maybe'…'good' means 'maybe.'" Harewood's bass drum then establishes the tempo of the upbeat But Not for Me. Remastered by AcousTech Like Minton's itself – a storied part of jazz lore that went through many iterations, reopening in 2006 only to close again last year – Up at Minton's appeared and reappeared several times after its initial release in 1961. It was reissued repeatedly on vinyl, CD and now for the first time on SACD by Analogue Productions Originals (APO). My first digital version was a two-fer released in 1994 that included each volume on a separate disc. Remastered by Ron McMaster, the two-fer sounded polite with a thin, brittle soundstage indicative of many early '90s CDs. It was then remastered by the original recording engineer, Rudy Van Gelder, as part of Japan's RVG series. The JRVG versions of Up at Minton's Volumes 1 & 2 were a touch more compressed than the McMaster versions, but in some respects sounded more vibrant and alive. Van Gelder breathed new life into Harewood's drums. The RVGs also featured a more forward, narrow presentation that seemed to fit to a "live" recording. Van Gelder claimed that his remasters better represented the sound of the original sessions, and he consulted his notes when working on these reissues. The novelty of having the engineer who recorded these sessions in the '60s involved again in the digital remastering was exciting, but sometimes the original recording engineer is not the best remaster engineer—especially for transferring original master tapes to digital. Thanks to Chad Kassem of Acoustic Sounds and Blue Heaven Studio as well as APO, some 50 Blue Note titles are being remastered by the industry's best: Kevin Gray and Steve Hoffman at AcousTech Mastering. Because of Kassem's deep love of blues and soul, all of these 50 titles titles shy away from Blue Note's more adventurous recordings. About the freest titles featured are Herbie Hancock's Maiden Voyage, which is tame fare compared to the avant garde recordings that many fans are demanding, such as Eric Dolphy's Out to Lunch. One can only hope future batches of Blue Note titles, including more adventurous sessions, are given the APO treatment. But Kassem may be wise to stick to straight ahead bebop, soul jazz and sessions based heavily on 12-bar blues compositions that tend to sell better. Up at Minton's certainly fits in that wheelhouse, serving up tasty blues and growling bursts of soul over a clockwork of solid bebop rhythm. But how does the sound compare on different digital versions of this interesting recording? JRVG Versus SACD The APO version is significantly better than the RVG, especially in the midrange. The piano, sax and guitar appear tonally improved with overtones in greater abundance. And they image better, with a wider, deeper soundstage. The guitar doesn't sound as gritty or "digital" on the APO. The bass may be a touch more pronounced on the RVG, but it is somewhat recessed throughout Live at Minton's relative to Blue Note's studio recordings. Drums and treble have slightly more "pop" and realism, especially in the high hat sizzle of Harewood's drum kit. Despite the small ensemble, there is some congestion in the recording – especially when Parlan hammers his block chords. The sound becomes a bit muddled. But when he plays a melody of single notes, each one seems to pop with more realism, overtones and dimensionality. This may be due at least partially to the venue. Minton's was never known for its audio attributes and the audio engineering was undoubtedly tricky there, compared to the Rudy Van Gelder studio. Perhaps the most telltale sounds of the recording are the varied crowd noises. Like Parlan's block chords, the clapping becomes congested when the whole audience is going. But as the applause tapers off, it is very realistic when only one or two people clap. Some voices floating in and out have an almost spooky realism on the SACD. Up at Minton's is certainly an interesting recording, and better represented on this new version than any previous digital release. As Volume 1 draws to a close amid a smattering of applause, Stanley Turrentine tells the crowd, "Now we'd like to take a brief intermission for some 'al-kee-hol.'" One can only hope Volume 2 is not far behind. Interestingly, the artwork for the SACD is a bit misleading. All songs of both volumes are listed. It seems possible both albums could have been included on a single SACD, but APO didn't produce it this way. I was fortunate to hear Stanley Turrentine perform up at Yoshi's. But now the best way to hear Turrentine live is on APO's Up at Minton's. And for that, Chad Kassem as well as Kevin Gray and Steve Hoffman deserve the applause, as well as Stanley Turrentine's quintet. Another winner from APO. One can only hope, as APO's initial batch of 50 is completed, this is not the end but the beginning of a bigger push to release Blue Note's catalog on SACD. * Two excellent titles by The Three Sounds have been released by APO on audiophile vinyl and SACD: Introducing The Three Sounds and Bottoms Up! – be sure to check them out.

|