|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 53

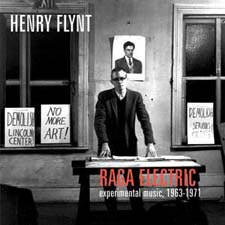

Nada Raga, Henry

Flynt

Raga Electric: Experimental Music, 1963-1971. Locust 6, Locust Music

I'm on my way out of Ear Candy Music, one of the jewels of Missoula, Montana as far as I'm concerned, anxious, as I always am in record stores, caught between a unquenchable desire for new music and the guilt of owning hundreds of CDs and records, and asking myself why I am shopping for more music when money is tight and I just spent 750 bucks on a new Soundsmith Boheme cartridge after the college student who cleans our house every other week snapped the stylus off my Virtuoso Wood, even though I told her not to dust the system (though, the Boheme is so much more satisfying than the Wood I almost want to thank her!), and this was the SECOND time in a year someone snapped the stylus off the Wood (my daughter said she watched the seven-year-old brother of her friend walk up to the ‘table and swing his finger tooop on the tip of the stylus), and I think, why not just a quick flip through the experimental music section? There's a Henry Flynt record! Raga Electric. Nineteen bucks! Heck, it's almost Christmas. It can be a present to myself.

I have been in amazement of Flynt since hearing his New American Ethnic Music Volume 1, after reading a review of it in The Wire. Powerful, ecstatic, electric violin hillbilly raga droney music. Just the sort of stuff I love! If I could amplify my mridangam with a lot of reverb or somehow some feedback, maybe I could sound a little like this.

Late at night a couple of days later, I play side one. On the first piece, Marines Hymn, Flynt plucks an electric guitar or violin like a tambura and sings like a Hare Krishna from Alabama, solemnly praising a deity in an unknown language. Several listens later, I realize he is singing just what the piece is called (AKA The Halls of Montezuma) in a kind of croaking Hindustani style, and I find his transformation of this jingoist boast into a kind of devotional song both moving and creepy.

The next four pieces, Central Park Transverse Vocal #1 - #4 are snippets, six seconds to a minute and half long. #1 is vocal sounds, like Flynt's doing calisthenics with his voice. #2 is more vocal noises—breathing, gargling, choking sounds. He's fooling around, looking for something. #3 and #4 are cries of gibberish. What's he up to?

The final cut on side one, the title cut, is raga-like guitar playing with more vocal noises, like LaMonte Young's singing in his Dreamhouse music, but much wilder, with yelps, like he's trying to work himself into an ecstatic state or figure something out. It's got the passion and conviction, from the guts feel, of Howlin' Wolf, who comes to mind because a friend and I listened to his The Real Folk Blues last week.

A couple of days later, I listen to side two, a single cut, Free Alto. Thirteen minutes of Flynt playing on the alto. No proper pitches, just a procession of squeezed out notes, like a mute trying to force speech from defective vocal cords and a ruined tongue. Free Alto, but not, I think, free, as in free jazz. I hear Flynt trying to blow the alto free from any associations with previous alto sounds, free, almost, from being an alto sax.

What's Flynt up to? I ask myself again. What's the experiment in this music? I think Flynt's trying to break past everything he knows to unknown sounds, using exotic music (Hindustani classical) and primitive, unschooled techniques to make sounds free of his enculturation, knowing he can never entirely escape what he knows. Maybe that's the pain, the darkness, the longing and frustration I hear in this music. Flynt faces his instruments and all the music he's heard as both means and barriers to transcendence, to his own music, imagined maybe, but as yet unnamed, unknown, nothing. Raga Electric is a record of Flynt's search for his nothing, which is, for me, something provocative, inspiring, and sometimes wonderful.

|