|

You are reading the older HTML site Positive Feedback ISSUE 44july/august 2009

RADIO FREE CHIP

Think Yiddish, Talk British, Dress Italian.

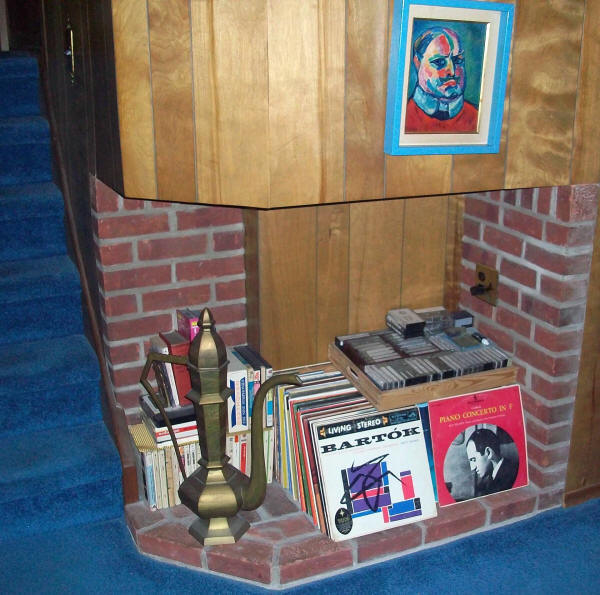

Jim Coleman The Audio/Video Salon RADIO FREE CHIP ...We are looking to evolve the manner in which we communicate with our readers, and to share our thoughts on music and audio, and those areas where it all intersects with my life—and yours. Gear reviews are hardly irrelevant, but I find myself going through changes, and this, our initial attempt at a column format reflects that journey. People have been transiting in and out of my life, and while it was surely not my intention for this column's maiden voyage, themes of spirit and sound, friendship and family, love and loss, seemed to run through my recollections and contemplations of sound, and the means of experiencing it and reproducing it. I know this is not making much sense, and I hope it doesn't come across as morbid, hopefully more reflective... even whimsical or celebratory at points. I was originally thinking about my early days as collegian working in the radio, station and how much fun it was to share a free form radio experience. In any event, let's see how this all plays out, shall we? And by all means, feel free to communicate with me via e-mail if you have any comments or questions or wish to participate in the process. Have a good summer, everyone, and thanks for all of the good vibes and kind thoughts. HOME IS WHERE THE HEART IS ... I have from time to time, referenced the living room in my parents' Plainview, Long Island home, where my mother Shirley Stern, still lives, fifty-some years later. My father, Martin was a natural artist and engineer, so things that involved electrician and carpentry skills were second nature to him and that listening room retains his aura and remains a remarkable acoustic space all these years later. Every time I have cause to be there, and take the time to give some CD a listen, I am reminded anew of the visceral reactions I had to all manner of sounds in this exalted portal of good music. I learned to really cherish all of my listening experience in my father and mother's acoustic space, with its hardwood walls, thickly carpeted floors, heavy furniture and L-Shaped configuration. Back in the day, as I have oft times written, the centerpiece of my parents' audio system were the original AR3a loudspeakers, which I believe are still poking around in my mother's basement; they also had a GE integrated amp and tuner, a Dual turntable and a Sony reel-to-reel tape recorder. Not to mention a very nice collection of classical music: most of the Heifetz violin concertos on RCA Red Seal, the Beethoven and Brahms symphonies by Joseph Krips and Bruno Walter, Fritz Reiner's famous RCA Red Seal edition of Bartok's Concerto For Orchestra, and Gershwin's Concerto In F; as well as a varied sampling of great Broadway musicals from the '40s and '50s, and such cool jazz vocalists as Frank Sinatra, Sarah Vaughan and Dinah Washington.

Over time, I helped my mother upgrade her system piecemeal over time with some DIY loudspeakers containing Cabasse drivers, a Marantz Receiver, a Denon CD changer and a Denon Dubbing Cassette deck. For tweaks I provided some JPS Labs Ultraconductor interconnects and a JPS Labs Power AC Outlet Center...more than that would've freaked her out, and when my father originally configured the system, we ran speaker wire under the floor, through the basement ceiling and up through the back of the dining room, where the loudspeakers were. When we purchased an earlier iteration of my Mom's system from Jim Coleman at the Audio/Video Salon (including the Denon pieces), he arranged from someone to set up the system for my mother, and run some fresh speaker wire through the floorboard, and I chose to leave well enough alone (seeing as how it was like a 25-30 foot run). But when all is said and done, the amazing thing about this audio system is not the gear, but the sound of that room itself.

Even with those big loudspeakers sitting up on wooden cabinets, and situated flush in corners of the room—a big no-no, way too close to reflective surfaces—the transparency, the soundstaging breadth and depth of the gives me goose bumps. There are tone controls on the Marantz Receiver (which Rabbi Michael Fremer was nice enough to help me get for my mom at an accommodation price back when I first began writing for his own imprint, The Tracking Angle and for Stereophile shortly thereafter), thus I am able to roll off some bass, so things don't get shrouded or heavy. And yes, these are nice loudspeakers and the system itself is more than adequate for my Mom's needs...still there is no way to comprehend the sound of the room itself. Images are so clearly drawn, and one has am exceptionally realistic portrayal of front to back information, quite a trick with less than a foot between the loudspeakers and the back wall. Go figure.

I reckon that all of that hardwood paneling and thick carpeting and heavy furniture stifles reflections significantly, while the JPS Labs interconnects and AC Outlet Center surely enhances signal to noise and pumps up resolution. Nevertheless, as best I can figure, it's the room folks, IT'S THE ROOM, which is something audio scribes have long tried to communicate to well-heeled Pilgrims going through reams and reams of gear in search of some spiritual lost chord, when they would be better off taking a simpler approach.

That is to say, you don't listen to loudspeakers in an anechoic chamber; but in an acoustic space, where they couple and interact with the room, which on many levels changes their behavior, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. Which is why a speaker may be conservatively rated down to 42Hz, and yet they are reproducing and projecting and dynamically articulating bass notes clearly right down to the bottom of the piano. Illustrating that the degree to which you can temper or enhance the natural acoustics of the room, is every bit as critical as the quality of the gear, which is not in any way meant to undervalue good gear. Anyway, I don't want to go into a big technical exegesis or get people reaching for their spectrum analyzers. I just wanted to share with your some sense about how I developed such a devout feeling for music. Hey, dig the cathedral/mosque effect my father crafted with the doors he situated over the bay windows both behind the loudspeakers and behind the big couch at the other end of the living room. And my Mom was always about good and good music—I used to read history and listen to Beethoven's Egmont Overture in that room. And now, with my mother's 84th birthday having just passed, facing a juncture in the road, her time of transit drawing nigh... I find myself thinking back to myself as a little boy, to my dad and mom, and to that room. Over the years, every time I visited my mother, I would be sure to bring a couple of CDs and cassettes to audition, just to see if I still got the same buzz I did as a boy, and I was always captivated by how involving, how rapturous the immersion experience in that room remains to this day. This was my father and mother's vision. My father passed away in the fall of 1967; John Coltrane passed away that summer (Trane was 40; my dad was a few weeks shy of his 43rd birthday). Leaving my mother as the matriarch of the family, always there for us all, and now as I pen this column, as she prepares to roll the dice on the surgeon's art, we are all on pins and needles, hoping not only that she might come through a daunting operation, but that she has enough will and fortitude to come through an exhaustive and extended rehab as well—and share her spirit with us for a little while longer. There is never any easy way to say goodbye, and the moment of truth always arrives far too soon, but my mother has led a good life, a feisty, independent-minded woman, who always kept her own consul, content with a few close friends, happiest on summer retreats to the Tanglewood Music Festival, in her own skin, and in her own home. That home, where I first experienced the spiritual dimension of sound. That room, where I sat in wonder at the power of music. That room, where I experienced a purity of resolution, degrees of presence and dimensionality, and levels of dynamic realism that I found myself pursuing most of my adult life.

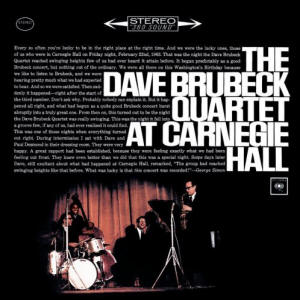

My father's spirit resides in that room. My mother lies in a hospital bed in a state of grace, and her spirit suffuses that whole house, much as it animates all of my experiences of music and literature. No, I am not ready for her to be a spirit, but I am preparing for any an all eventualities. Or as Papa Jo Jones liked to say, "Into every reign, a little life must fall." Or as I told her the last time I visited, "Hey, Mom, a few trillion light years aren't going to come between us." What was that sound? AN AMERICAN TREASURE ...The Dave Brubeck Quartet in its second iteration—when the great pianist-composer and his alto saxophone doppelganger Paul Desmond were joined by the great bassist Eugene Wright and drummer Joe Morello—was one of the most esteemed recording and performing ensembles in the history of jazz, and most of you are undoubtedly familiar with their famous 1959 recording Time Out, which introduced a number of memorable jazz standards in what were then considered rather esoteric time signatures. I have long admired and respected Dave Brubeck as a man and as a musician, as a force for change in human relations and as a man deeply committed to the roots of jazz, who nevertheless looked to expand on its root vocabulary by referencing his deep love for and knowledge of traditional and modern western classical music, and he was always looking to introduce polytonal, polyrhythmic and contrapuntal elements into the collective dialog. And for this, at the height of his popular breakthrough, he had to eat a lot of politically correct shit from pseudo-hipster, pseudo-liberal jive artists masquerading as "critics" for having the effrontery to be both white and popular. The one time I had the opportunity to interview this gracious gentleman, I got the distinct impression those jabs and put-downs still hurt decades later. Never mind that approaching the age of 90, Brubeck is still hard, still out there, still making gigs and turning out superb recordings for the Telarc label, such as a wonderful solo piano recording from 2004, Private Brubeck Remembers, which reprises the music of a generation of young men who went overseas during World War II and left their sweethearts behind, never sure if they would ever see each other again. It manages to balance ambiguity and nostalgia, throwaway tunes and real classics in a way that is at once quite touching and swinging, without ever indulging in cheap sentiment—wonderful performance and wonderful sonics. Never mind that four of his six children (pianist Darius, drummer Dan, trombonist-bassist Chris and cellist Matthew) are excellent musicians in their own right, and often collaborate with their father. Never mind that on one hand you can clearly hear the likes of Jelly Roll Morton, Willie "The Lion" Smith, Fats Waller, Count Basie and Milt Buckner echoing about in Brubeck's deeply informed historical perspective of the American piano. Never mind that in the extensive body of work for Fantasy Records (which he helped found) that precede his classic quartet days, some of his experiments in modern music were such that you could subsequently trace his influence on the likes of such avant gardists as Cecil Taylor. Never mind that along with Max Roach, Brubeck's musical sojourns beyond common time have led to generations of musicians for whom complex metric transitions through different time signatures are no longer a daunting challenge, but part and parcel of the modern musical vocabulary. Never mind that countless jazz musicians, including no less an innovator than Miles Davis, have turned to such superlative Brubeck jazz standards as "In Your Own Sweet Way" and "The Duke," and found something of themselves in their lilting melodies and sophisticated harmonies. Never mind that he fronted a fully integrated Army band, that performed all over Europe for a decidedly segregationist American Army, during World War II. Never mind that the classic Brubeck Quartet featured a virtuoso African-American bassist, Eugene Wright, who brought a degree of rhythmic and harmonic sophistication that was at once both cutting edge and firmly rooted in the Walter Page/Count Basie rhythmic tradition, nor that Brubeck would routinely turn down lucrative bookings at colleges and performance venues where any semblance of segregation was tolerated. Never mind that Dave and his wife Iola Brubeck always championed human rights, never more so than when they wrote and produced a jazz operetta for the great Louis Armstrong that was an alternately satirical/inspired call for liberation and freedom and humanistic values, coming hot on the heels of Brown V. Board of Education, when Jim Crow America was still lurching its way along in the days before the Civil Rights and Voting Rights legislation of the mid-60s.

The Real Ambassadors was recorded at Columbia's acoustically splendid 30th Street Studios in the fall of 1961, and last enjoyed a commercial release on CD in 1994 for the Sony Legacy label (I was privileged to speak with Dave and pen the liner notes for this re-issue): besides Louis, it featured a Brubeck piano trio with Eugene Wright and Joe Morello; the Louis Armstrong All-Stars; the great vocalist Carmen McRae and the remarkable vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. In part it referenced the hypocrisy of employing American jazz musicians such as Louis Armstrong as goodwill ambassadors, capable of dissipating anti-American student riots on their State Department tours (as Dizzy Gillespie did back in Greece during 1956) while back at home in the land of the free, African-Americans endured legal apartheid. In 1962, there was a performance of "The Real Ambassadors" at the Monterey Jazz Festival, but it has never enjoyed a public performance since, although the Hartford-based jazz vocalist Dianne Mower has launched a web site (http://therealambassadors.com/) dedicated to bringing Dave & Iola's work to Broadway. Still, while this 1961 recording features wonderful aural qualities to complement its superlative arrangements and performances, the CD is inexplicably out of print, so while I would urge you to keep an ear out for it (and look for downloads), the Brubeck CD I am going to hip you to, that has been in heaviest rotation as a reference recording every time I am looking to A/B audio gear (or am just down for some musical pleasure), is The Dave Brubeck Quartet at Carnegie Hall (Sony). In his recollections of this showcase gig from February 22, 1963, Brubeck relates how it occurred smack dab in the middle of a newspaper strike, and the band wasn't sure anyone would even show up. But they ended up playing before a packed house, and from the moment they launched into their opening number, "St. Louis Blues," it was clear to everyone on stage and in the audience that the band was on fire. But their fire is informed by the unmistakable grace and relaxation of a band whose skills have been honed over hundreds and hundreds of live gigs and recordings to the point where they are able to create spontaneous responses and collective orchestrations in the moment that transcend all of their intellectual preparations and conscious decision-making... what Art Blakey characterized as "direct from the creator to the artist to you..." That rarefied state where a band looks forward to getting lost, so that they can share the magic of collectively finding their way out of the darkness and back into the light (and vice a versa)—a process of discovery where musical comrades share a fresh and unexpected perspectives on familiar terrain. You can feel that vibe on every track and the recorded sound only amplifies the emotional intensity and aw shucks swing with which the band gets in and out of every situation. There is a lovely balance between the stage sound and the hall sound, which to me is particularly powerful on their reading of "Blue Rondo a la Turk" where the band emerges from the jagged formality of the famous 9/8 set-up into a glorious medium-up pulse imbued with a blues feeling, and man is Paul Desmond ever swinging, every melodic phrase browned and burnished in clarified butter and floating dreamily over the a deliriously laid back Wright/Morello stroll. You can hear Desmond reveling in how the sound of his saxophone comes back to him from the hall, and in a sense the ambience of the hall is dictating his tempo; you can hear the enormity of that sound as it projects into the farthest tiers of the hall, and over a couple of choruses the saxophonist gradually breaks into purer and purer vocal exhortations, as he toys with the outlines of an old popular song whose melodic outlines I recognize but whose title I cannot call up for you; still I can clearly apprehend the lyrics (and so can Brubeck, giving Paul an audible amen) as Desmond stretches the words like taffy and seems to intone "...on olllllllllddddddd Broaddddddddwaaaaaaay..." before tying things up with a surprisingly down home testimony. Brubeck then digs deeper into the groove beginning with big two-handed chords, then down-shifting into teasing little single-note blues phrases, introducing subtle little polytonal touches as Wright and Morello settle into an elemental shuffle (and you can clearly dig the palpable weight of Wright's acoustic bass, the sparkle and presence of Morello's top cymbal and snare as they he move air). As Brubeck begins to double up rhythmically into a very powerful evocation of his stride roots, they echo his emotional and physical complexity, bringing things to a dynamic catharsis.

It is a conclusive moment, but the band rewards the audience with a very loosey-goosey, near eastern-flavored coda on "Take Five," and as on the band's other readings of the Time Out and Time Further Out repertoire (such as an utterly charming version of "Three To Get Ready" which leads into the first intermission), their interpretation of this material has grown far less formal and self-conscious, altogether warmer and more confidently swinging, and the manner in which the recording captures Morello's melodic cross-rhythms and accents on the toms is just remarkable (as is the drummer's wide-ranging series of rhythmic events on his feature showcase, "Castilian Drums"). Rarely have rhythm instruments been portrayed with such presence and warmth (dig Wright's bass on his "King for a Day" feature), nor has a live recording maintained a better, more natural balance between piano and drums (though good microphone work notwithstanding, clearly much of that balance derives from Brubeck and Morello's hands and ears). But with the passing of time, I find myself returning more and more to the band's elemental workout on "Pennies From Heaven" where you can hear the band's deep grounding in and love for the Ellington/Basie tradition, and where the levels of interplay and swing are damn near telepathic—four men swinging and singing as one. I particularly love the way Brubeck deconstructs and abstracts the theme, like a cat playing with a mouse, before teasing Morello into syncopated give and take with some of those big, joyous, resounding, big band chordal flourishes...and I am not sure any of you have ever read this in a Dave Brubeck review, and if not, let me the first—Dave is a funky motherfucker. And as they take the theme out, Brubeck and Desmond engage in a bit of elegant contrapuntal whimsy before settling on a shoot the ticket to my John Boy closing right out of the Basie/Jo Jones reader. Damn...now that's jazz—one of greatest concert recordings ever, by one of American music's greatest bands. There is a good reason why many of you reading all of this loquacious, celebratory prose have invested so much emotionally and economically in good audio systems, and that being the case The Dave Brubeck Quartet at Carnegie Hall should be a stocking stuffer for all seasons. Rarely has a concert recording made the sense of venue, the shared feelings of inspiration, the give and take between band and audience seem more live and in the moment. So what exactly are you waiting for, Pilgrims, your own personal stimulus plan? Only five more shopping months till Xmas. SOUNDINGS ... When my friend and colleague John Potis passed away over the Christmas holidays as 2008 drew to a close, a little something of me went with him. It's not as though my enthusiasm for high end audio has waned appreciably, but John and I were brothers in music, who regularly shared our experiences, and as such, there remains a hole in my spiritual ozone layer. This thing of ours, as much as it addresses our fascination with gear, an exultation of technology or the joys of music, is ultimately about sharing. If you have a really good bottle of wine, while one may surely derive personal pleasure from its layers of complexity, as a solitary experience it pales besides the community of emotions one may enjoy when others are able to offer an amen chorus attesting to those qualities which you find so moving—not unlike the pleasure I derive over the course of an intense collective improvisation with my band mates. So while I continue to explore different pathways of sound, I find that in the absence of a spiritual sounding board, such as my man Otis, the process of evaluation has a different meaning to me, and I am far less inclined to delve into the epic mode which has marked my expositions since I began documenting my thoughts on audio topics for Stereophile back in 1996. Of course, what for Chip Stern represents an abridged format, remains a pretty expansive essay by community standards and I unquestionably remain a loquacious lad. Still, we are trying to rein things in a tad, and this new column format thus represents an attempt to telescope my emotions and reactions in a more casual, conversational style regarding gear, in the context of musical and personal experiences...and communicating my reactions in a slightly less exhaustive manner—more alone the lines of how I might respond to an e-mail inquiry from a reader asking me to handicap some thoroughbreds. I don't know if that is what we have accomplished with this maiden voyage, but those were my thoughts going in. And so, having rung in the New Year with a remembrance of John Potis, we followed-up with an exhaustive and enthusiastic review of the Luxman DU-80 Multi Standard Music Player, and I now find myself contemplating a number of audio components which got backed up on the runway during our rites of passage. My curiosity about all three of these pieces was inspired by John Potis' personal experience of them. Much as I would reference and direct gear his way—to share the musical experience and satisfy my own curiosity as to John's insightful analysis and perspective—likewise, John would pull my coat to things he wanted to reference from my point of view. Yes, sharing is a beautiful thing. These were all pieces of gear that Potis and I had discussed at great length, and which in some way shape or form were things he had introduced to me, based on his own enthusiasm, experience (and ownership). In fact, our original notion was to take on each piece of gear in a more or less tag team manner, a double-header review of sorts, the better to formalize the ever-evolving nature of the back and forth which distinguished our phone marathons. It was John who originally introduced me to the joys of the bel canto e.One REF1000 monoblocks (which he had reviewed and subsequently purchased); likewise the Thiel CS2.4 loudspeakers also had a place of honor in his living room...and so inspired, he graciously made intros to the estimable John Stronczer, bel canto honcho/designer (an old school tube man who had gone whole hog into analog switching technology, employing ICE power modules), and Micah Sheveloff, who does PR/Marketing for such esteemed high end audio icons as Thiel, Bryston and Savant Systems (and who is a terrific keyboardist, fronting his own band, the Voodoo Jets while currently engaged in perfecting arrangements for his solo project, Exhibitionist, with an eye towards a 2010 release). Meanwhile, everyone knows EveAnna Manley, the charismatic, creative dynamo in charge of Manley Labs, an industry trendsetter in both Pro Sound/Recording and High End Audio, and I took great pleasure in putting John on her radar screen. Given John's experience of these audio archetypes, he encouraged me to take a dip into the pool, and likewise, given my experience of Rogue Audio tube pre-amps and power amps (over the course of several reviews in Stereophile and Positive Feedback), I encouraged John to check them out—feeling that a fresh set of ears and expectations would afford readers with a fresher perspectiver. So I in turn introduced John Potis to Rogue's Mark O'Brien. Well, I enjoyed my experience of the bel canto REF1000 monoblocks for Positive Feedback; and while John had originally been interested in auditioning the Cronus integrated amp, I encouraged him to check out separates from Rogue's Titan Series, which had received less attention in the press. John's review of the Rogue Atlas power amp and Metis pre-amp turned out to be one of the most passionate, perceptive pieces he ever penned, and we discussed it quite a bit in the fall of 2008. John was quite taken by the value and sheer audio verity of both pieces, in particular the surprising impact and top to bottom frequency extension he experienced in digging the Atlas' EL34-based circuitry, which to his ears, were unique both in terms of sonics and value. To John, the midrange sound of the Rogue Atlas was so right, so in the pocket, that his experience of its frequency extremes (so uncharacteristically sweet and punchy) gave him pause. And as we went back and forth over the phone, comparing and contrasting our experience of sundry EL34 circuits, we became more and more intrigued about the sonic possibilities of Manley Labs' 100 watt EL-34 based monoblocks, the Snappers—first introduced back in 2002. Not only did the encompass a number of evolutionary refinements, but they held a place of honor in EvaAnna's own home system (she feels, with good reason, that they represent the most advanced, up-to-the-minute expressions of Manley Labs vacuum tube technology, and that they offer consumers the best sound and value in the Manley line). Ironically enough, John was actually planning to rekindle his relationship with the online audio magazine SoundStage at the time of his passing, so our plans on becoming a high end audio tag team would likely not have borne fruit, but as all the gear was already in the pipeline, I resolved to proceed as a solo wrestler. So there you have it: let's give the Manley Snapper monoblocks a listen and move on to the fully tweaked, divinely evolved new Mark II iterations of the bel canto monoblocks I liked so much in Issue 38 of Positive Feedback On Line (though our follow-up references their new REF500 monoblocks) and the Thiel CS2.4SE (a more elegant accoutered, sonically tweaked iteration of the stock CS2.4 loudspeakers that John reviewed) in upcoming columns—Potis' spirit and friendship continue to shadow me. Sporting an aquatic nom de plume—as has been the case with such popular Manley amplifier designs as the Stingray (an 8 X EL84 integrated amp, offering 20 watts triode/40 watts UltraLinear), the Mahi (a monoblock version of the Stingray), the Jumbo Shrimp and Wave pre-amps, the Steelhead pre/phono stage and the Skipjack 4-into-1/3-into-2 audiophile source selector—from the moment I plugged in the Snappers, I was quite taken and not a little nonplussed by their sonic signature. Quite taken because there was a richness of detail and a sense of ease, intimacy and bloom to the presentation that is part and parcel of the EL34 experience. And a little nonplussed because there was a degree of dynamic impact to the low end and a sense of sparkle and presence and openness to the high frequencies that seemed to validate many of the expectations Potis and I had for a new generation of EL34 circuitry.

In auditioning solo drum/percussion tracks from Milford Graves' Grand Unification and Stories on one end of the sonic/aesthetic spectrum, and some recent rock and roll CD purchases (The Beatles 1 and the Stones Tattoo You) on the other, one of the first things I was brought up short by the abundant reserves of power and dynamic headroom, and consequently by how convincing the timing and rhythmic aspects of the music were. Where some EL34 circuits ingratiate themselves with a warm, sumptuous midrange—equal parts triode and my ode—the customary trade-offs are a perceptible softening of the treble and a palpable degree of high frequency roll-off, with noticeably diminished punch in the low frequencies. Now, while my experience suggests that the low end slam of the Rogue M150 monoblocks is bigger and more immediate, the Snappers are most definitely no slouch in this department and they reproduced the double bass drum transients in Graves' kit with visceral realism, without compromising the rich and varied pallet of midrange information (in the form of a dizzying array of complex stickings and hand-drum like inflections on a variety of wood, skin and metal instruments) or the exquisite depiction of an acoustic venue that master recording engineer Jim Anderson so routinely captures in his best work. And from the earthy presence of McCartney's Hofner bass on the earliest Beatles tracks to the elemental snap, crackle and pop that the most recent re-masters reveal of the Watts/Wyman rhythm team on the anthemic "Start Me Up", there was a palpable sense of vitality to the song's foundation that conveyed the 10th row sensation of a live stage feed and acoustic projection in triplicate, while fleshing out the immense complexity of the Richards-Woods guitar tapestries (the ancient art of weaving, indeed) and Jagger's vocals—all the while fleshing out captivating studio aura and spatial cues of the mix. How do they achieve this aural balancing act? Manley Labs points to their fully differential circuit topology and a balanced signal path, resulting in a high-signal-to-noise ratio and enhanced "signal detail," while their sophisticated new output transformer and a "...portly 180 Joule energy storage reservoir in the main B+ supply channel" contribute to full bandwidth current reserves capable of delivering transient swings you can believe in.

And for this listener—who invariably eschews the pentode of tetrode mode in favor of the triode (no surprises, there)—the Snapper's UltraLinear circuitry affords listeners a nice balance of slam and refinement, with refinement having the final say at events. UltraLinear, or partial triode as Manley references it, has been defined as "a blend of triode and pentode, in which the screen-grid has a percentage (between 0% and 100%) of the plate's output signal impressed on it... usually achieved by incorporating a suitable "tap" on the primary winding of the output transformer that the vacuum-tube is connected to." Furthermore, Manley Labs feels that an UltraLinear output stage is more tolerant of a wider variety of output load conditions than pure pentode What I found particularly pleasing about the Manley Snapper's UltraLinear configuration was its depiction of the transition from the upper mids to the top end (and beyond), where the intoxicating chocolate liqueur creaminess of EL34 tubes is often a double-edged sword, the Lord giving and the Lord taking away in one fell swoop. And in deploying some choice SACD and DVD-A source materials, I was able to glean a particularly fulsome portrait of the Snapper's elegant yet fulsome sonic signature. On The Great Jazz Trio's performance of "Caravan" from the DSD recording Someday My Prince Will Come (Eighty-Eight's) the Snapper didn't simply do a superlative job of conveying the impact of stick on bronze, but the very presence, hang time and decay of Elvin Jones' cymbals were dead on in my estimation (something I have experienced up close and personal many times over the past 40 years)—as was how well the amp helped convey a believable sense of an acoustic space, while fleshing out images and maintaining distinction between Hank Jones' piano and Richard Davis' bass (to particular effect on those tracks where he deployed his bow). The ability of an amp to not only convey the timing of music but its very atmospherics is manifest in string music, and on two very different recordings—the DVD-A of Joni Mitchell's Both Sides Now (Reprise) and one of those typically superb DSD recordings from the Scandinavian 2L label (String Quartets, by the Engegårdkvartetten Ensemble)—the Snappers demonstrated a propensity not only for muscle, but for light and air. On darkly poetic renditions of popular standards from the jazz singer's songbook, producer Larry Klein frames Mitchell's smoky, mezzo flotations in verdant autumnal layers of strings, low brass and woodwinds, a devoutly painterly background, where from time to time, the high brass reaches out and bites you. But again, dig how the dryly recorded cymbals and snare on "Comes Love" and "Sometimes I'm Happy" retain a realistic (if slightly distant) perspective and maintain their delicate distinction against the rising waves of brass and receding pads of flutes, affording a nice sense of air to the proceedings, while the piano and bass have just enough weight and pop to stand out from the orchestra (without being overwhelmed). This is a nice trick on such a Lady In Satin-type production, and the Snappers mange to convey the entrancing richness and distinction of the orchestra's complex array of midrange voices, while shadowing Joni's smoothly inflected vocals (and Wayne Shorter's tenor on "Don't Worry About Me") in lush textures without sacrificing air and transparency on the top end, the subtle weight of the rhythm section on the bottom, or the subtle buoyancy and distinction of the lead voice at the heart of the midrange—talk about bandwidth. And on the Engegårdkvartetten Ensemble's readings of string quartets by Haydn, Grieg and Leif Solberg, I was particularly taken by the glistening sheen and understated sparkle of the top end, and how the Snappers helped convey complex layers of fundamentals and overtones, grounded in the Earth, seemingly ascending without a ceiling into interstellar space. Nope, as far as EL34 circuits go, the Manley Snappers ain't your father's Oldsmobile. And they are sexy, stylish little fishes to boot, with their six sided chassis, sloped back panel and a quartet of spiked stanchions which elevate the main chassis and reduce vibrations. Sporting a quartet of EL34 output tubes per side, with 12AT input tube and 7044 and 5687 tubes in the driver stage they put out an honest 100 watts of UltraLinear sushi into an eight ohm load. Yet for all the heft, solidity and apparent build quality, these babies weigh in at a very practical 38 pounds per side, run nice and quiet and allow end users the option of single-ended or fully balanced operation for $4250 a pair. What more is there to say? The Manley Snappers have the subtlety and midrange layering to reward deep immersion into complex textures on one hand, and naked vocals on the other, without sacrificing sweetness or slam.

Will they prove bloomy and rapturous enough for your standard issue EL-34 fan? Well, you tell me, but I strongly suspect that some listeners may surely prefer more lushly apportioned depictions of sound in a pure-triode configuration, and that the degree to which the sound is skewed to showcase the midrange may prove more subjectively pleasing to fans of high-sensitivity loudspeakers and source music with greater degrees of texture and less prodigious transient swings. For those, like myself, who love acoustic music and subtle ambient cues, but who may frequently be found in the throes of wham-bam-thank-you-maam—for whom the manner in which a system can convey both the power and the subtlety of the drum set is paramount—the Manley Snappers proved eminently likeable indeed. Did I like them as much as my reference Rogue Audio M150 monoblocks? Yes, pretty much, though they will not be supplanting them in my reference system. In their portrayal of music there are many things they both do superbly, and at roughly similar price points (the M150 go for $4495), both excel at getting out of the way and allowing you to listen to the music, not the tubes, which will certainly recommend them more to some listeners than to others. Where they differ is mostly in perspective, and in that sense the choice of circuitry and output tubes plays some part. Having said that, the Rogues offer end-users a step up in power and a choice between pure triode and UltraLinear operation on-the fly. In addition, I've always been so happy with the way the M150's sounded with KT88 output tubes, that I availed myself of the option to deploy EL34 or 6550 output tubes. I suspect that if I biased up a set of EL-34s in the M150s, I might very well hear inside the music in ways that would remind me of the Snappers (and please recall that this audio journey derives in part from Brother Potis' enthusiasm for the EL-34 configured Rogue Atlas). So yes, there sure is something to be said for the Snapper's EL-34 circuitry and how deeply it allows you to hear into the music, not that the Rogues are any slouch in the midrange department, and both amps offer superb bandwidth and linearity and transient speed and image illumination and soundstaging breadth, depth and height from top to bottom—a musically compelling, balanced sound. All things being equal, with one amp employing EL-34s and the other KT-88s, please Mister Chip, say something conclusive—declare a winner.

Sorry, but that's not my job. Perhaps though, we can relate one final impression based on some initial listening experiences with that Bill Frisell, Ron Carter, Paul Motian (Nonesuch) trio recording that I reference in damn near every review. At that time, with both amps in house and on the amp stand, I thought that the Rogues had a little more dynamic heft and a slightly more expansive sound (remember that they may be operated in both UltraLinear and triode mode), but that I was hearing a little deeper into the soundstage with the Manley Snappers, discerning some midrange details in the sound of the drum kit and Paul Motian's cymbals that I wasn't altogether certain I had heard before with the Rogues. Maybe I was buzzed, or just exulting in the sound of the new. But both amps sounded pretty bloody good, and both blithely drove such different loads as the Joseph RM25siMkII, the Thiel CS2.4SE and the Dynaudio Confidence C1 to full orgasm without any apparent strain or distracting distortions. I could find little to quibble about with the Manley Snappers, and neither will you. I am pretty sure John Potis would've dug them. What was it that actor Tom Hulce said as Mozart in a humorous scene from the movie Amadeus? In the process of trying on all of these wonderful wigs, he just couldn't, decide, and finally blurted out, "I wish I had two heads" (followed by that cachinnating laugh). A nice problem to have, which brings us back to a fundamental principle of high end audio, which is that if you can't be with the one you love, love the one you're with. If I hadn't already fallen head over heels in love with the Rogue M150 monoblocks, it might've been a lot harder to pack up the Manley Snappers and send them back to their Chino, California home. Still, if I may be indulged one final movie metaphor, as Monsieur Felix (the stamp dealer) told Audrey Hepburn's Regina Lampert character in Charade—upon contemplating three of the rarest, most valuable stamps in the collectors' firmament—"For a few hours, they were mine... that is enough." JOHN POTIS FAMILY RELIEF FUND ...John Potis is survived by his wife Becca, and two daughters aged 12 and 9, Danielle and Gracie. A POTIS FAMILY RELIEF FUND has been established for contributions to help his family. Cash contributions can be made by sending a check or money order to Potis Family Relief Fund, 13510 Blenheim Road N., Phoenix, MD 21131. Contributions can also be sent through PayPal to ID [email protected]. Donations in kind can be made by contacting Eric Luebehusen at 202-720-3361 or [email protected]. Donations in kind will be auctioned off on www.audiogon.com and all proceeds will go to the Potis Family Relief Fund. For further information, you may contact Vinh Vu of Gingko Audio ([email protected]). Chip Stern Manley Labs http://www.manleylabs.com

Snappers

|